Here’s an article about Merton and the Catholic Worker that I wrote for the CW in 1978, ten years after Merton’s death. It’s a topic I’ve now explored more thoroughly in a book —"The Root of War is Fear: Thomas Merton's Advice to Peacemakers" — that Orbis will publish later this year. (Thanks to Gerry Twomey for doing this.) Jim

|

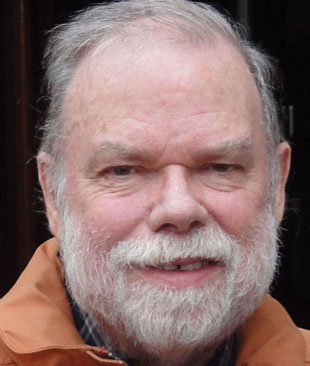

| Father Louis (Thomas) Merton O.C.S.O |

by Jim Forest

published in the December 1978 issue of The Catholic Worker

| |

The Catholic Worker, if not exactly respectable today, was even less so two decades ago, when Thomas Merton’s correspondence with Dorothy Day was beginning. It was before Popes John XXIII and Paul VI and the Second Vatican Council, when few Catholics had heard of pacifism or conscientious objection and that had thought that these had something to do with being a Quaker. One didn’t have to search far to find priests that regarded the Catholic Worker’s ideas on war and peace as mildly heretical. The Catholic Worker struck many as unfathomably bizarre: a paradox as odd as any G.K. Chesterton had imagined. Capping the Catholic Worker’s public image at the time were the annual rituals of arrest, when Dorothy would be seen in news photographs standing in front of city hall instead of taking shelter in the subways during a dress rehearsal for nuclear war. The Cardinal put up with the Catholic Worker, it was generally assumed, ignoring its peculiar opinions in admiration for the free soup and hospitality it offered the down-and-out.

At that time, the idea that Thomas Merton, one of the most well-known and respected writers in the Catholic Church, would be writing Dorothy respectful, appreciative letters—not only about the hospitality of the Catholic Worker but about its protest activities—would have struck us as wildly improbable.

It was at Christmas time, 1960 that I remember a group of us at the CW sitting at the large dining room table of the Peter Maurin Farm in rural Staten Island, that beautiful place that has since disappeared under the march of suburban housing. The air smelled of tea and the bread Deane Mowrer had baked earlier in the day.

Dorothy was reading aloud from various letters received, something she often did, always adding her own commentary, which could be devastatingly funny affectionate, but grumpy if the letter were too complimentary.

‘Here is one from Thomas Merton,’ she said, opening and envelope from the Abbey of Gethsemani in Kentucky.

The name was enough to lower the tea cups and open the ears to maximum width.

‘Again, I am touched by your witness for peace,’ the letter began. ‘You are right in going at it along the lines of Satyagraha.’

We knew enough of Gandhi to recognize the rarely heard word. It meant a way of action rooted in the force of truth alone.

‘I see no other way,’ he went on, ‘though of course the angles of the problem are not all clear. I am certainly with you in taking some kind of stand and acting accordingly. Nowadays, it is no longer a question of who is right but who is at least not a criminal, if any of us can say that anymore. So don’t worry about whether or not in every point you are right according to everybody’s book: you are right before God as far as you can go and you are fighting for a truth that is clear enough. What more can anybody do?’

His letters came fairly often. At times there were packages as well. At times there were packages as well—clothes contributed by a monk taking first vows, some Trappist cheese, even a side of smoked bacon one Christmas. (The bacon came with a card in Merton’s hand—‘From Uncle Louie and the Boys.’ In his monastic community, Merton was Fr. Louis. The ‘boys’ were the novices under his charge).

Rereading his autobiography, The Seven Storey Mountain, one realizes Merton’s interest in the Worker’s peace work had deep roots in his earlier life. Much of his childhood had been in France and England, where the scars of the First World War were fresh. On one holiday, hiking along the Rhine Valley in Germany, he had nearly been run down by a car full of young Nazis, scattering leaflets in favor of Hitler’s election. He saw no point in imitating the Nazis in order to defeat them. After his conversion to Catholicism, he was one of the rare Catholics to register as a conscientious objector. Though he was willing to be a battlefield medic, the army (to his relief) wouldn’t have him, with or without guns, with or without a conscience: he didn’t have enough teeth.

His first public statement on Christian responsibility regarding war appeared in the October 1961 Catholic Worker. Entitled ‘The Root of War is Fear,’ the bulk of it was for New Seeds of Contemplation, a book he was preparing for publication. But a long section was written especially for The Catholic Worker. There was no logical reason for the utter devastation of nuclear war, he argued, yet the world was plunging mindlessly in that direction, and doing so in the name of peace. ‘It is true war madness, an illness of the mind and spirit that is spreading with a furious and subtle contagion over all the world.’ So bad was the situation that many Americans were building ‘bomb shelters where, in case of nuclear war, they will simply bake slowly, instead of burning quickly…’

Christian Responsibility

What is the Christian responsibility in the midst of such insanity? ‘Is he simply to fold his hands and resign himself for the worst, accepting it as the inescapable will of God and preparing himself to enter heaven with a sigh of relief… Or, worse still, should he take a hard-headed and practical attitude and join in the madness of the war-makers, calculating how by ‘first strike,’ the glorious Christian west can eliminate atheistic communism and user in the millennium?’

But what then to do?

Here followed as firm a statement of Christian duty as one can find anywhere in Merton’s published writing:

“The duty of the Christian in this crisis is to strive, with all his power and intelligence, with all his faith, his hope in Christ, and love for god and man, to do the one ask God has imposed upon us in the world today. That task is to work for the total abolition of war… It is a problem of terrifying complexity and magnitude, for which the Church itself is not bully able to see clear and decisive solutions. Yet she must lead the way of nonviolent settlement of difficulties and toward the gradual abolition of war as the way of settling international or civil disputes. Christian must become active in every possible way, mobilize all their resources for the fight against war. First of all, there is much to be studied, much to be learned. Peace is to be preached, nonviolence is to be explained as a practical method, and not left to be mocked as an outlet for crackpots who want to make a show of themselves. Prayer and sacrifices must be used as the most effective spiritual weapons in the war against war, and like all weapons, they must be used with deliberate aim; not just with a vague aspiration for peace and security, but against violence and war.’

Disarmament of nations requires a foundation of personal disarmament. ‘This implies,’ he went on, ‘that we are also willing to sacrifice and refrain our own instinct for violence and aggressiveness in our relations with other people.’

He was urgent but not at all optimistic about what could be accomplished. ‘We may never succeed, but whether we succeed or not, the duty is evident. It is the great Christian task of our time. Everything else is secondary…’

Following his own advice in the years that followed, Merton maintained a very busy correspondence with various persons and many groups working against war: Catholic Peace Fellowship, Pax (now Pax Christi) and the Fellowship of Reconciliation. He offered his counsel, his writings, his prayers and occasionally, his hospitality.

Much of his correspondence had a critical edge. His thought obviously challenged generals, but he could trouble his fellow pacifists equally well.

Among the main tendencies in the peace movement in the mid-sixties was ‘politicization.’ Political ‘analysis’ blossomed in pacifist circles much as they did in the Left. Plain words, like ‘suffering’ were replaced with such abstract words like ‘oppression.’ Increasingly, the universe was viewed through class and economic lenses. Pacifists seemed increasingly embarrassed not to be in possession of the annual reports of the multinational corporations. To offer the Sermon on the Mount as one’s political point of departure seemed, to a growing number of pacifists, like confessing to imbecility. The process deeply disturbed Merton, who recognized in it not only a decisive step away from pacifism but away from religious faith and the turning of human beings into ideological decimals.

Repeatedly he sought to reinforce a different spirit among pacifist groups with which he corresponded. As he expressed it on one letter:

‘The whole problem is inner change… an application of spiritual forces and not the use merely of political pressure. We all have the great need for purity of soul, that is, the deep need to possess in us the Holy Spirit, to be possessed by Him. This has to take precedence over everything else. If He lives and works in us, then our activity will be true and our witness with generate love of truth, even that we may be persecuted and beaten down in apparent incomprehension.’

Another letter emphasized what he called the ‘human dimension’:

‘The basic problem is not political, it is a-political and human. One of the most important things to do is keep cutting deliberately through political lines and barriers and emphasizing the fact that these are largely fabrications and that there is another dimension, a genuine reality, totally opposed to the fictions of politics: the human dimensions which politics pretend to arrogate entirely to themselves. This is the necessary first step along the long way toward the perhaps impossible task of purifying humanizing and somehow illuminating politics themselves.’

This required of pacifist groups a radical non-alignment with power blocs of both right and left: a manifestly non-political witness: non- aligned, non-labeled, fighting for the reality of man and his rights and needs in the nuclear world in some numbers against all alignments.’

Hence the importance of those who side with none of the forces of killing to maintain their independence and could not be absorbed in united-front coalition campaigns in which the protesters are not so much against war as against one side in the war. It reminded Merton of his experiences with the Left while a student at Columbia, which he was briefly a member of the Community Party, with the secret party name Frank Swift. “The primary duty of all honest movements,’ he counseled, ‘is to protect themselves from being swallowed up by any sea monster that happens along. Once the swallowing has taken place, rigidity replaces truth and there is no more possibility of dialogue: the old lines are hardened and the weapons slide into position for the kill once more.’

Another aspect of peace activity that disturbed him was a pacifist minority identity that expressed itself in various forms of self-righteousness, infecting protest so that it only drives opponents further apart. A deep longing for transformation, of oneself as well as others needed to animate activities for peace, and that required a genuine respect and sympathy with those whom protest located on ‘the other side.’ We must, he wrote the Catholic Worker, ‘always direction our action toward opening people’s eyes to the truth, and if they are blinded, we must try to be sure we did nothing specifically to blind them. Yet there is that danger: the danger one observes subtly in tight groups like families and monastic communities, where the martyr for the right sometimes thrives on making his persecutors terribly and visibly wrong, to see refuge in the wrong, to seek refuge in violence.’

Without compassion, protest tends simply to play on the guilt of one’s opponents. “There is,’ Merton wrote, ‘no finer torment.’

Merton’s difficulties with the peace groups he belonged to came to a crisis point for him late in 1965, when the intensity of the peace movement, reflecting the escalation of the war, began to acquire what Merton saw as an ominous spirit of irrationality.

While not holding the Catholic Worker or the Catholic Peace Fellowship responsible, Merton felt obliged to end his public identification with peace groups that he felt were creating a climate of protest which led in what seemed to be a desperate direction. He sensed, he wrote, ‘something demonic at work,’ not only in the war-making society but in movements of protest as well.

‘The spirit of this country at the present moment is to me terribly disturbing… It is not quite like Nazi Germany, certainly not like Soviet Russia, it is like nothing on earth I ever heard of before. The whole atmosphere is crazy, not even the peace movement, everybody. There is in it such an air of absurdity and moral voice, even where conscience and morality are invoked (as they are by everybody). The joint is going into a slow frenzy. The country is nuts.’

Merton’s vulnerability had been heightened by his recent move into a hermitage on the monastery property where he was a newcomer to a more intense solitude than had been possible before. Though more hidden from the world than previously, he felt his connections in every direction more intensely than ever.

Within a month, after much correspondence with several friends, he changed his mind, even going so far as to issue though the Catholic Peace Fellowship a public statement about the permission he had received to live as a hermit and his decision, nonetheless, to remain a Catholic Peace Fellowship sponsor. He wanted to continue to support groups ‘striving to spread the teachings of the Gospel and the Church on war, peace and the brotherhood of man.’ His public association did not mean, however, that he approved of everything individual members of such peace groups might undertake on their own responsibility. ‘I personally believe,’ he wrote ‘that what we need most today is patient, constructive and pastoral work rather than acts of defiance which antagonize the average person without enlightening him.’

Merton reached his position with considerable care, though often with false starts. He listened with close attention to what friends had to say, and was quite capable of changing his mind. But he would allow no one else to do his thinking for him. Thus it continually alarmed him to see mob mentality building up even in groups that were protesting the government’s mob mentality. One’s convictions, so often, were nothing more than absorbing unexamined the opinions of peers Even those in peace groups, he pointed out, very often had n real anchoring point for their spiritual or intellectual lives, no senses of the need carefully to establish the foundations of one’s life.

His own values, as he made clear in action as well as word, were formed in the Catholic Church and his monastic vocation. He became less and less parochial with the passage of years but never because of the erosion of his primary religious commitments.

He believed strongly in the disciplines of religious life, in a rather unfashionable way. For more than a year, for example, beginning in the spring of 1962, he was ordered not to write on war-peace issues—a decision he accepted, though with quite audible protest. He said the order was arbitrary, uncomprehending, discouraging, insensitive, disreputable and absurd—but that to disobey would only te taken with his community ‘as a witness against the peace movement’ confirming others in ‘their prejudices and self-complacency.’ It would be nice to ‘blast off’ about it but ‘I am not merely looking for opportunities to blast off.’ He pointed out he had chosen to live in a religious community where one voluntarily accepted limitations: ‘I may or may not agree with the ostensible reasons why the limitations are imposed, but I accept limits out of the love for God Who is using these things to attain ends which I myself cannot at the moment see or comprehend… I find no contradiction between love and obedience, and as a matter of fact it is the only sane way of transcending the limits and arbitrariness of ill-advised commands.’

The point of view seemed medieval to many readers, for whom the right of disobedience towards authorities easily poured into the religious sphere as well. At the Catholic Worker, Dorothy Day had long expressed similar commitments in obedience within the Church, as strongly as she opposed blind obedience to the state. In this regard, more ‘radical’ (as we imagined) younger staff members took exception.

Merton’s point, and Dorothy’s too, was that it wasn’t enough to be right about one’s opinions. One had to live them out in a way that opened others to them—even if that meant shutting up for a time. Nonviolence was something that meant shutting up for a time. Nonviolence was something more than a new methodology although bloodless for clubbing people over the head.

Then silenced, Merton wasn’t, however, altogether silent. His peace writings, in mimeographed form, flowed freely from The Catholic Worker, Catholic Peace Fellowship and other similar channels. It was a bit like the Soviet literary underground.

He continued to publish as well, but under invented names. He signed on article in The Catholic Worker with the by-line Benedict Monk. That was rather a thin disguise. A letter in Jubilee bore the signature Marco J. Frisbee. For anyone familiar with Merton’s particular sense of humor, that was a giveaway as well. As things worked out, what Merton had been stopped from saying was taken up by Pope John XXIII and later the Second Vatican Council. ‘Pacem in Terris,’ published by the Pope [John XXIII] is 1963 offered the first clear papal support to conscientious objection. A just war, the Holy Father stated, was no longer possible: ‘In this age of ours that takes pride in nuclear weapons, it is irrational to argue that war can any longer be a fit instrument of justice.’ The encyclical listed and discussed fundamental human rights, beginning with the right to life.

It is probable that Merton’s writings had a direct influence on Pope John’s thinking. Certainly Pope John held Merton in high esteem—so much so that after his election as Pope, he sent Merton one of the vestments—his stole, that he had worn [after] the coronation. (In 1966, Pope Paull made a similar gesture of appreciation to Merton, entrusting small bronze cross to [Merton’s monastic secretary] Brother Patrick Hart for personal delivery to Merton in Kentucky. A formal written blessing to ‘Thomas Merton, Hermit’ hung in his hermitage inside the closet door as Merton would have it—the hideout in his hideout).

It is important to remember of course that he was, in his last years, still Thomas Merton, Monk, not Thomas Merton, would-be Catholic Worker, or Thomas Merton, would-be Buddhist, Zen Master, or any of the things people sometimes try to make of him to bring him closer to their own ideals.

What is remarkable to those who haven’t lived the monastic life and imagine it as a situation cutting off the monk from reality and ‘the world’ is the discovery, in a monk’s life made public through writing, of how intensely his vocation joined him to may efforts outside themonastery, especially responses to human suffering. Thus Merton’s long association with the Catholic Worker movement and his personal sense of identification with others, especially the poor. As he commented in a letter about the slow processing by Trappist censors to an article he had written for The Catholic Worker, ‘This is the kind of thing one has to be patient with. It is wearying, of course. However, it is all I can offer [in sharing the lot of the poor]. A poor man has to sit and wait and wait and wait, in clinics, in offices, in places where you sign papers, in police stations, etc. And he has nothing to say about it. At least there is an element of prayer for me, too.’

At the center of his spirituality was his hope in God, whom he spoke of at times as ‘Mercy within Mercy within Mercy.’ The hope required patience and poverty of spirit, not a frantic and optimistic expectation of what one was bound to accomplish. As he put this in one of his most helpful letters, written me in 1966, two years before his death:

‘Do not depend on the hope of results. When you are doing the sort of work that you (in the Catholic Worker and Catholic Peace Fellowship) have taken on, essentially an apostolic work, you may have to face the fact that the world will be apparently worthless and even achieve not results at all, if not perhaps the opposite of what you would expect. As you get used to this idea, you start more and more to concentrate not on the results but on the value, the rightness, the truth of the work itself. And there too a great deal has to be done through as gradually you struggle less and less for an ideal and more and more for specific people. The range tends to narrow down, but in gets much more real. In the end, it is the reality of personal relationships that saves everything.

It is so easy to get engrossed with ideas and slogans and myths that in the end one is left holding the bag empty, with no trace of meaning left in it. And then the temptation is to yell louder than ever in order to make the meaning be there again by magic.

The big results are not in your hands or mine but they suddenly happen and we can share in them, but there is no point in building our lives on this personal satisfaction which may be denied us and which, after all, is not all that important.

The real hope, then, is not something we think we can do, but in God Who is making something good out of it in some way we cannot see. If we can do His will, we will be helping in the process. But we will not necessarily know about it beforehand.’

[A more detailed study of themes in this article appears in essays by Jim Forest and Gordon Zahn contained in a book published this month, THOMAS MERTON: PROPHET IN THE BELLY OF A PARADOX, Paulist Press, Gerald Twomey, editor].

|

| Jim Forest |

Accompanying this article, the editors of The Catholic Worker included a segment on the bottom of page four that detailed Merton’s publications in the paper during his lifetime under the headings: “articles”; “book reviews”; and, “poetry,” along with excerpts from five of those pieces that appeared in the CW on topics under “Merton on Faith and Violence”: “The Root of War” (October, 1961); “Christian Ethics and Nuclear War” (March, 1962); “The Shelter Ethic” (November, 1961); “We Have to Make Ourselves Heard” (May, 1962); and, “We Have to Make Ourselves Heard: Part II” (June, 1962). Although it was a “lay paper,” during his lifetime twenty-eight of Merton’s publications appeared in the CW, from April, 1949 (“Poverty”) through his letter to Jim Forest, “A Letter to a Young Activist,” published posthumously in December, 1977 (for the complete text of Merton’s February 21, 1966 letter to Jim Forest, see Christine M. Bochen (ed.), “Letter to a Peacemaker” [James H. Forest], Thomas Merton: Essential Writings (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2001), pp. 135-136 or William H. Shannon (ed.), Thomas Merton: The Hidden Ground of Love/Letters on Religious Experience and Social Concerns (NY: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1985), pp. 294-297.

The editors included this note on page four: “During the last twenty years of his life Thomas Merton made the following contributions to The Catholic Worker:

Articles: Poverty, April ’49; The Root of War, Oct., ’61; The Shelter Ethic, Nov. ’61; On the General Strike for Peace, Feb. ’62; Christian Ethics and Nuclear War, March ’62; Ethics and War, A Footnote, April ’62; We Have to Make Ourselves Heard, May ’62; part two, June ’62; St. Maximus the Confessor on Nonviolence, September ’65; No More Strangers, Feb. ’66; Albert Camus and the Church, Dec. ’66; Ishi—A Meditation, March-Aril ’67; The Shoshaneans, June ’67; Auschwitz, A family Camp, Nov. ’67; War and Vision: The Autobiography of a Crow Indian, Dec. ’67; The Sacred City, Jan. ’68; The Vietnam War: An Overwhelming Atrocity, May ’68; The Wild Places, June, ‘68; Letter to a Young Activist (posthum.), Dec. ’77.

Book Review: Zen in Japanese Art, July-Aug., ’67.

Poetry: Clairvaux Prison Jan. ’48; Chant to be Used in Processions Around a Site with Furnaces July-Aug., ’61; Advice to a Young Prophet Jan., ’62; Soldiers of Peace Jan ’63; An Ideal City Jan. ’68.

Most of these writings are available in Thomas Merton on Peace (McCall Pub., 1969); New Seeds of Contemplation (New Directions, 1961); Ishi Means Man (Unicorn Press, 1976); Selected Poems (New Directions, 1967).

* * *

From: Gerald S. Twomey <gerald.s.twomey@gmail.com>

Date: Sat, Jan 30, 2016 at 5:44 AM

Subject: This format that I typed up might work better for you if you choose to e-blast it or post it on your website.

To: Jim Forest <jhforest@gmail.com>

No comments:

Post a Comment