At the Reformation, the new religion was met by the population with less than enthusiasm, which probably explains why so many carvings and stained glass have remained untouched to the present day. The Catholic gentry and their employees provided ample work for Jesuit priests who had a "college" ( a community of priests) in Hereford, and the Catholic presence remained strong until the failure of the 1745 rebellion of Bonny Prince Charlie, after which the Catholic landowners gave up hope of any Catholic restoration and went with their servants to Maryland in the American colonies. Even among the Anglican clergy, there were those in the early days who celebrated the Book of Common Prayer service in their parish churches and then went home, away from the spying eyes of the authorities, and celebrated the pre-Reformation Mass for those who were interested. Nowadays, however, Herefordshire is a very Anglican county, and Hereford has one of the highest numbers of Anglican churches in proportion to the population in the country.

It is also said that one of the oldest witches covens in the country actually still meets in this area, which is why, they say, so many churches are dedicated to St Michael and his angels, including Belmont Abbey, and there is a chapel of St Michael built over the entrance of the cathedral to keep out unwelcome visitors! Perhaps, just a rumour!

KILPECK CHURCH

The name Kilpeck is derived from Kil or Cell and the name of the saint Pedic or Pedoric. The church is dedicated to St Mary and St David. This St David is not the patron saint of Wales but another local St David.

The name "Kilpeck" clearly pre-dates the chapel and castle and is typical in Celtic Christianity. It was the place where a local monk, St Pedic or Pedoric, had his cell or monastery. These local saints, often monastic hermits, had immense influence, with even bishops seeking advice on spiritual matters and guidance on how to run the church. Their memory lived on in the local Church and where they lived was often marked by a chapel bearing their name. There are references to "Cilpedec" in the 7th century, dedicated to St David, probably a local saint rather than the patron of Wales.

The church at Kilpeck is quite fascinating. The ornately carved door contains elements of Celtic, Saxon and even Scandinavian (Viking) art and is seen as the epitome of the Herefordshire school of sculpture. It is built on a seven-sided or egg-shaped mound which may indicate the site was used in antiquity but this is open to debate. The church is ornately carved with no less than 89 corbels.

Before we go any further, please watch the following video, after which I am going to suggest an overall interpretation of the many carvings in the church which is based, not on what each carving means as an isolated artefact, but on an integrated pattern of symbols that tell us what a Catholic church is for. We must remember that this is a church built by Catholics for Catholics, not Catholics during the Reformation which was caused by a clash of doctrinal definitions, but Catholics of a time when East and West were at least partially joined together and when the "age of the fathers" was still very much alive. They read Scripture differently in those days, using the images and stories from the New Testament, especially the death and resurrection of Christ, as a key to understanding the images and stories of the Old Testament, the reality showing us the real meaning of its shadow. This is also the way the Liturgy understands Scripture. Please watch the video.

Some time ago, I visited the small church of Kilpeck and the first thing that struck me was what a wonderful setting it would be for the celebration of the Divine Liturgy of St John Chrysostom or, for that matter, the celebration of any

truly Catholic Eucharist. Thus I came to look at the carvings both within and without in a liturgical frame of mind.

Then it struck me that the Eucharist is the key to understanding the meaning of the carvings, not of each one taken individually, but the theme that binds them all together in a coherent whole. The liturgy is "heaven on earth" and, therefore, the interior of the church represents heaven because it is where the liturgy is celebrated. The chaotic juxtaposition of pagan and Christian symbols on the exterior represents the world in which the Christian lives, but the Spirit that descends on the Church in the Eucharist forms an undercurrent, uniting the created world with Christ in heaven.

If the Eucharist is the central theme, then we must begin with the sanctuary and the altar, the most sacred part of the church called the apse. It is on the altar of any church that heaven and earth meet..

Over this altar, there is a carving of water cascading down along the stone seams, onto and around the altar table, and from there, it flows down the centre of the chancel and nave.

I quote from an Orthodox essay on water, but in this regard, the author is giving the Tradition common both to East and West:

For thousands of years water has been among the main religious symbols. This is indeed the case for the Orthodox Christian tradition where it is involved in liturgical mysteries from baptism and the Eucharist to the rites of the Blessing of the waters. Why is water so central to Christian religious life? Let us attempt to answer this question by turning to Biblical history and Christian tradition with particular reference to the office of Epiphany.

Water as a symbol of life as well as a means of cleansing, or purification, is of particular importance in Old Testament. It was created on the first day (Genesis 1:2, 6-8). The Spirit of God was hovering over the face of the waters (Genesis 1:2). The earth was founded upon the waters (Genesis 1:6-7, 9-10). God commanded the water to bring out an abundance of living souls (Genesis 1:20-21). In some sense the element is close to God (Psalms 17; 28:3; 76:17, 20; 103:3; 148:4). God is compared with the rain (Hosea 6:3). Water brings life (cf. Exodus 15:23-35; 17:2-7; Psalms 1:3; 22:2; 41:2; 64:10; 77:20; Isaiah 35:6-7; 58:11) and joy (Psalm 45:5). It is a powerful purifying element and can destroy evil and enemies as in the stories of the Flood and the flight of Israel from Egypt (Genesis 3:1-15; Exodus 14:1-15:21). According to Old Testament Law, it cleanses defilement (Leviticus 11:32; 13:58; 14:8, 9; 15-17; 22:6; cf. Isaiah 1:16) and is used in sacrifices (Leviticus 1:9, 13; 6:28; 1 Kings 18:30-39), in which context the Bible mentions the living water (Leviticus 14; Numbers 5; 19). Water heals, as can be seen from the stories of Naaman the Syrian cured from his leprosy in the waters of Jordan (2 Kings 5:1-14) and the annual miracles at Bethesda in Jerusalem (John 5:1-4). John the Baptist used the waters of the Jordan to cleanse people's sins which reminded typical Jewish custom (Matthew 3:1-6; Mark 1:4-5; Luke 3:2-16; John 1:26-33) - even Christ came to be baptized (Matthew 3:16; Mark 1:10). On the other hand, water is also the habitat of serpents whose heads God crushed (Psalm 73:13-14) and of the dragon (Job 41:25; Psalm 103:26).

We can see from this the belief common in the Old Testament that water is a mystically powerful element which, being connected with God in some way, can cleanse sins, inner and outer defilement, and regenerate the human body. It is even possible to assert that water has taken on the religious symbol of life.

In the sanctuary of Kilpeck church the reference, I think, is to the water that gave life to the Garden of Eden, but more especially to the water that flows from the heavenly temple in Jerusalem in Ezekiel 47, 1 - 12:

The man brought me back to the entrance of the temple, and I saw water coming out from under the threshold of the temple toward the east (for the temple faced east). The water was coming down from under the south side of the temple, south of the altar.... [3] As the man went eastward with a measuring line in his hand, he measured off a thousand cubits and then led me through water that was ankle-deep. [4] He measured off another thousand cubits and led me through water that was knee-deep. He measured off another thousand and led me through water that was up to the waist. [5] He measured off another thousand, but now it was a river that I could not cross because the water had risen and was deep enough to swim in — a river that no one could cross. [6] He asked me, “Son of man, do you see this?” Then he led me back to the bank of the river. [7] When I arrived there, I saw a great number of trees on each side of the river. [8] He said to me, “This water flows toward the eastern region and goes down into the Arabah, where it enters the Sea. When it empties into the Sea, the water there becomes fresh. [9] Swarms of living creatures will live wherever the river flows. There will be large numbers of fish because this water flows there and makes the salt water fresh; so where the river flows everything will live. [10] Fishermen will stand along the shore; from En Gedi to En Eglaim there will be places for spreading nets. The fish will be of many kinds — like the fish of the Great Sea. [11] But the swamps and marshes will not become fresh; they will be left for salt. [12] Fruit trees of all kinds will grow on both banks of the river. Their leaves will not wither, nor will their fruit fail. Every month they will bear because the water from the sanctuary flows to them. Their fruit will serve for food and their leaves for healing.”In Catholic understanding, this river is the Holy Spirit, the source of life for the Church and the source of life for the Liturgy. As it says in the passage. "Where the river flows, everything will live."

The water descends on the bread and wine and on the community when the priest, in the name of Christ, presents a petition asking the Father to send his Spirit on the bread and wine to make them the body and blood of Christ and on the community so that it may become capable of sharing in the heavenly Liturgy (Hebrews 12, and the Book of Revelation as a whole).

The Holy Spirit is seen as the force that unites the eucharistic community with the ascended Christ to become one body with him as it prays "Holy, holy, holy" with the angels and saints. It joins them as Christ enters into the heavenly sanctuary, united with those from the whole of humanity, past, present, and future, who are saved by this intimate union with him as they become his captives of love.

The liturgy is “this unprecedented power that the river of life exercises in the humanity of the risen Christ”.

The liturgy is “eternal (inasmuch as the body of Christ remains incorruptible) and will not pass away; on the contrary, it is this liturgy that “causes” the present world “to pass” into the glory of the Father in an ever more efficacious great Pasch” (63).The liturgy essentially involves action and energy; the heavenly liturgy tells us of all the actors in the drama: Christ and the Father, the Holy Spirit, the angels and all living things, the people of God (whether already enjoying incorruptible life or still living through the great tribulation), the prince of this world, and the powers that worship him. The heavenly liturgy is “apocalyptic” in the original sense of the word: it “reveals” everything in the very moment in which it brings it to pass.

When the event is present, prophecy becomes “apocalyptic”.

The liturgy is this vast reflux of love in which everything turns into life.

Jean Corbon "The Wellspring of Worship"

We have this theme of water, coming down from heaven, going through the middle of the church, rising up in the doorway and producing the tree of life in the timpanum.

The liturgy is "heaven on earth", and this is the theme of the Church's interior. Therefore, the local congregation is never alone when it has been brought into the presence of the Triune God in the Mass: as Hebrews and the Apocalypse indicate, they form one community with the "whole Adam" as the early Fathers would say, and they stand, shoulder to shoulder, with the saints and angels. Thus no Catholic church is without statues or icons of the saints, and Kilpeck Church is no exception. They are on the columns that separate the chancel from the nave. Who the saints are I don't know, but the churchgoers would have known by what the saints are carrying. Anyway, they indicate the close connection between heaven and earth which have become united by the Incarnation.

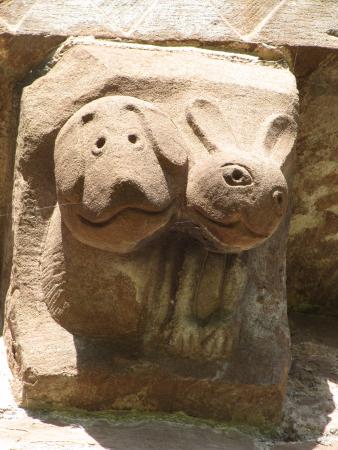

The outside carvings collectively stand for the world in which we live. It is a mixed world in which there is both good and evil, love and lust, monsters and dangerous wild animals that eat human beings, but also rabbits and pigs, humour and human affection. Perhaps the horse and cross represent the anonymous Templars who pass through this world bearing Christ's Cross and are buried in the church without names.

A SELECTION OF CORBELS

Human love and procreation

the famous Sheela Na Gig:

A pagan fertility goddess? A depiction of lust? This motif is found in other countries of western Europe, though this is the most famous and most photographed, and its origin is most probably Christian. The sculptor seems to be telling us that the world is a chaotic mixture of good and bad. If that is so, this may depict lust.

Finally, perhaps a symbol for the Templars or for all Crusaders who passed through this world serving the Cross:

No comments:

Post a Comment