Belmont monks at prayer

Christ is the light of angels

Angels are light to monks

[taken from a homily by Abbot Paul on the Feast of St Michael and All Angels]

“I tell you solemnly, you will see heaven laid open and, above the Son of Man, the angels of God ascending and descending.”

The first Christian monks believed that this word of Jesus to Nathanael was as much the basis of their vocation as the texts from the Acts of the Apostles describing the life of the first Christian community in Jerusalem. So together with the terms Apostolic Life and Coenobitic Life, the early monks and nuns used the term Angelic Life to describe the wonderful way to which the Lord had called them to live.

So the Belmont Community, that has the privilege of living under the protection of St Michael and All Angels is a community not just of apostles and coenobites: we are angels, for that is what God has called us to be like, a choir of angels.

And the longer you live in the community and get to know the brethren, the more you come to realise how true that is.

Why were the desert fathers so struck by the similarity of a monk’s life to that of an angel? To begin with, the Bible constantly tells us that the angels stand in God’s presence night and day singing his praises, worshipping his majesty, sharing in his glory, enjoying his presence, seeing his face. That is what a monk seeks to do, through the grace and mercy of God. We are aware of God’s presence not only when we gather together in church to celebrate the liturgy, but also in the refectory, the calefactory, the cloister, our cells, the parishes and other places where we work, in fact, wherever we happen to be. The desire to practise continuous prayer leads us to seek God and find him in all the circumstances of our lives, whatever we are doing, and in all people.

The Scriptures also tell us that the angels are God’s messengers and servants. Has it ever struck you that only an angel can evangelise? So our vocation, such a tremendous gift of God, calls us to proclaim the truth and the beauty of God’s word, the wisdom and the righteousness of his will, his extraordinary and gracious love for creation and for each one of his creatures. At the same time, we are called to serve the monastic community, our brethren, with charity and humility and without murmuring, as St Benedict repeatedly reminds us in the Holy Rule. And there is a wider call to service in the Church and in the world. Just think what Christian monks and nuns have contributed to mankind, to civilization, in so many areas of life.

In our abbey church, we are all aware of the many angels who surround us and accompany us in our prayer: they are just everywhere. Yet, the angels we see depicted in art are only a reminder of the countless angels we cannot see with our eyes but are truly present when we join in their song of adoration: Holy, Holy, Holy. They speak powerfully to us of what and who we are called to be in the mystery of God’s love and the intentions of his Divine heart. May today’s feast and this celebration help us remember that we must become as the angels, light as a feather on the breath of God in the singing of his praises, prophetic messengers and obedient servants of the Lord in preaching his word, nothing without Him but everything with Him.

Monastic Belmont

The life of the monastery

THE BENEDICTINE CHARISM TODAY

This is the second half of a talk given by Esther Waal. It begins HERE

This is the second half of a talk given by Esther Waal. It begins HERE

| Thomas Merton (Fr Luis) |

In recent years, I've come to much appreciation of Thomas Merton. There is a real prophetic person. If you haven't yet discovered Merton, you're very lucky for great riches await you. A Trappist monk, living therefore by the Rule of Benedict, I've come to know him recently through his photographs. They've told me a lot about the way he saw the world. They express how much he lived out of the Rule. Imagine Merton living in his hermitage outside the Abbey of Gethsemani in the blue Kentucky hills. The good friend who lent him his camera, John Howard Griffin, a remarkable journalist, said that the way Thomas Merton focused on people was also the way he focused on things. He was totally present to the person or thing before him. Listening, he let each person, each thing, have its own voice. He stood back never tying to possess, to label, to organize.

Merton didn't believe that we come to God through the truncation of our humanity but through the wholeness of our humanity. All the senses are to be valued. He told his novices that the body is good; listen to what it tells you. He recognized that all the senses, particularly the senses of sight, sound and touch can teach us much. In those hermitage years, he was nurtured by long periods of silence, getting up at two in the morning to pray. Those hours before dawn enfolded him in the gentleness of the world around his hermitage. He learned those relations with his body and the world about him produced joy, openness, and dialogue. I think that he used his camera to express this. He walked gently through the woods around the hermitage using his camera as a contemplative instrument. What and how he saw came out of his hours of prayer.

While writing a book on Merton using his photos, I saw that you've just got to stay with the simplicity of his vision, standing in front of piece of wood and some stones, which we otherwise might easily pass by. The texture and the relationship speak to him. Seeing an old workbench with a nail and all the scars of that battered wood, he stands back and lets it express itself in its own voice. He doesn't want to control or to possess. It's as if he goes beyond the things themselves to their essence, to the integrity of the things.

This is also true of Benedict. He is always moving beyond the individuals to the common, the corporate, the shared, the underlying essence, all the while saying that each individual person is unique and matters. The opening words to the Rule are totally personal: "Listen, carefully, my son," Benedict says, addressing each one of us, I believe, as the prodigal. The whole theme of the Rule is that each of us is the unique son or daughter of a loving Father, but each of us has gone astray. The whole purpose of the Rule is to bring us back to the embrace of the Creator Father. Each person is unique. And every single thing matters, which is why Benedict says something very profound in an almost absurd, throw-away line: "If anything gets broken or damaged in the pantry, own up at once." Own up at once because every single thing matters.

|

| Community meeting: Belmont Abbey |

Above all, Benedictine spirituality is a shared, common, corporate spirituality. We have all these good things to share with the whole of God's family. We are partners with God in handling all these good gifts. This isn't an individualistic or isolated spirituality. It's about community life in whatever shape or form that may take. For those of us who are living outside monastic communities, we expect that form to change throughout our lives, involving overlapping circles as we are inserted into a succession of relationships, including relationships with the non-human. Benedict touches a deep and universal truth which traditional peoples know. Time and again in Celtic understanding-- and you know it from Native American experience-- we see that we are inserted into the whole web of creation. It's important that we stay with this.

There is a sweeping tide of interest in spirituality which, in my most cynical moments, I think is making a spirituality one more consumer product, an offer of in-built success. You buy it, and with it comes the promise of ultimate or even instant success. I haven't read anything by Ariana Huntington, but she is noticed in England. I quote her from something that I read just before I left England. She said, "The contemporary spiritual search is like a gigantic medieval fare where we wander between stores and booths and hawkers selling promises, and these promises, I've attempted to say, come very close to the promise of self-discovery, self-fulfillment, the rented me-ism that can be so seductive."

Benedict takes us into the theme of unity and connectedness. And again we come back to images. When I first picked up the Rule in Canterbury, I discovered the way of Benedict not just through a written text but through the actual monastic buildings amongst which I was living. The buildings were an expression of the way life that was lived by a great monastic community during the Middle Ages. What was it that I experienced as I walked through the cloisters or past the granary, the brewhouse or the bakehouse at the end of the garden? I knew where the herb garden was and what had been the infirmary and the guest house. And not the least, I explored a marvelous succession of underground tunnels through which an enterprising 12th century prior brought piped water to the monastic community. They built these tunnels with enormous care and skill. Nobody would have seen them. Yet, they were made with beautifully cut stone, set in rounded arches to carry the lead pipes. This speaks of their care for infinite detail, whether they were piping water, growing herbs or welcoming guests.

|

| Ampleforth Abbey |

As I walked around the cloister, I saw all the buildings that depended on the cloister. Benedict's respect and reverence for the unity of body, mind, and spirit was set out before my eyes. There was the dormitory. Benedict says enough sleep is very important. Eight hours sleep is what he said. There was the refectory. He loved and respected food and wanted it to be carefully served with reverence. There was the scriptorium, expressing respect for the intellect, for extending and challenging the mind. And there at the base of it all, anchoring it, was the church telling us that everything must flow into prayer. This life is a seamless garment said Dominic Milroy OSB. And it's very appropriate that he should, since he's a Benedictine and the headmaster of England's biggest Benedictine school at Ampelforth. This holistic approach recognizes the importance of the whole of ourselves, body, mind and spirit, and the rhythm by which we let it be part of our daily life.

Someone who recently joined a Benedictine community reported, "We came expecting to be taught a prayer technique. Instead, you are told that when you take your shoes off, you put them parallel to each other and not pigeon-toed, that you should close the door behind you quietly, that you should walk calmly and eat slowly and leave things ready for the next person to use. At first I thought this stuff is for the beginners. The real stuff will come later on. Then I came to understand that that is the real thing. It is how we do the little actions that makes us mindful of God or our neighbor."

The fascinating thing about that quotation is that I have taken it from the sermon preached on Passion Sunday in an Anglican parish church in a small market town on the border of Wales, close to where I now live. It's a parish that was a Benedictine power in the Middle Ages. But that meant nothing to any of its people until a year ago when the rector and his wife spent two weeks in a Benedictine community in Normandy. It turned their lives around. They felt the warmth, the love and the care in the guest house, which made every meal a loving and sharing experience and built a gentle friendship between the guests and the community. They returned saying, "This is given to us, too, at a parish. Ordinary lay people are given this grace by the very fact of this place in which we worship. We neglected it, but now we will return to it as our vision and guide to deepen our community life in our very ordinary small market town. Ordinary people at the end of the 20th Century." Throughout Lent there has been teaching, study and discussion at this parish. And people, with amazement, say how liberating and natural this is. They say they are allowed to feel and live the way they deep down always wanted to live.

In that sermon, the priest told them, "When you stand at the kitchen stove, that is the center; that is the altar. When you lie in your bed, your bed becomes the altar. When you wash a dish or pick up litter, you are the altar. You are always standing on holy ground. Any moment can be the moment. Any place can be the place." He led them to see the image so powerfully given in the buildings themselves, that all these daily activities would be impossible were it not for the heart of the monastic building-- the empty space of the cloister. It is the cloister, the enclosure, that holds everything together. They are around an empty space in the middle that keeps everything together and in harmony. This empty space of the cloister garden is symbolic of something that runs all the way through the Rule, and that is the emptiness of the individual before God's constant presence. He went on to remind them of the Eastern saying that what allows the wheel to turn is the empty space that joins the axle bar of the cart to the wheel. Without that emptiness, the wheel won't turn.

Here I think of Thomas Merton's photograph of the great cartwheel he had outside his hermitage, which he photographed with such love and care. There, surely, is that image of the empty space at the heart of the monastic buildings, and of our own self too. For me that image was movingly expressed when I managed to get to Subiaco 18 months ago. In that monastery, the cloister is an inner cloister garth or garden. The garden was watered and made fruitful from a water system which stood in its center. The whole image of tending a garden and of the changing seasons of the garden is written out there.

I recently and movingly experienced the power of that inner cloister, that inner garth or garden, when I went back to South Africa. What took me to South Africa in the years of Apartheid was an invitation from Desmond Tutu. He asked me to do in South Africa what I had done in England, and to some extent in America. We had a Benedictine experience week in which we grew together, 25 people, using the Rule as a guide for our daily rhythm of praying, studying and working together. We formed a temporary lay community which drew its inspiration from the insights of St. Benedict. The people who came to live, work and pray together were drawn from all the divides of the South African church-- Dutch Reformed, Anglican, Presbyterian, Catholic-- and from the racial divides-- black, colored and white. These people haven't lived close together and shared their life together the way that we did that week. We did this first in Johannesburg then in Cape Town. And Benedict spoke to African consciousness because of this wonderful African concept of "ubunto." It's untranslatable, but Desmond Tutu expresses it with his favorite saying, "A person is a person in relation to other people." The South Africans were excited by what the Rule could give them. "Why was this good news kept from us?" they said. "Here is a wonderful tool. Here is a means we need to build the coming church in the new South Africa."

I went back after Christmas to have continuing conversations with people whom I had gotten to know well. When I was in Cape Town I visited a place that is no longer a living monastery because the monks have left it. Imagine with me this simple monastic building built from a very simple courtyard. The chapel, the kitchen, the refectory and so on run off the foreside. The cells above look down into the central open space. No longer used as a monastic building, it has become a trauma center for the victims of racial conflict, torture, exile, suffering and violence that have troubled South Africa in recent years. As the warden greeted me, he had no idea who I was. He didn't know that I was interested in monastic tradition. He greeted me saying, "This place is, in itself, healing. It's healing just to cross this threshold, just to stand here with this courtyard opening up before us with the sense of the prayers of the monks who are no longer here. But their presence through their prayers is still with us. This is the start of the healing process for these damaged people as they come here, and it begins just as soon as they cross this threshold." I found it so moving that I went to my bag to get the trauma center's simple logo, which pictures prison bars where the bars have become flowering branches with the promise of new life.

And so, the cloister or the enclosure makes possible the welcome and the openness to those in need. And so, we have this picture of the open door depending on the cloister, whether it is written out in the monastic buildings and lived out in a strictly monastic community, or whether it is the principle by which we live that openness, that unity, refusing to be filled up which leads to exhaustion, tiredness, depression. Benedict wants energy for us. He is a man who writes with vibrancy and urgency. Above all he wants the church and society to get behind the divide, the dualities, the divisions and the splits to that centeredness by which we can hold things together. From that center, we can reach out with the loving welcome, the fullness of hospitality that is so much the Benedictine charism.

I end with a quotation from Merton's Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander. Merton writes: "There is nothing whatsoever about the ghetto spirit in St. Benedict. That is the wonderful thing about the Rule and about Benedict himself, the freshness, the freedom, the sanity, the broadness, and the healthiness of the Benedictine life." This man gives us a sign, a promise and a challenge as much today as when the Rule was written. Shall we in our generation be able to handle the gift of Benedict's Rule with respect, reverence, and responsibility and share this gift with others?

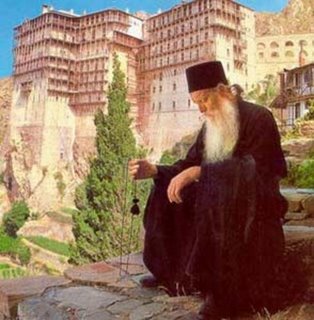

IMPORTANCE OF MONASTICISM FOR ORTHODOXY TODAY

PAPER PRESENTED BY METROPOLITAN HILARION OF VOLOKOLAMSK AT THE ROUND TABLE OF 4TH INTERNATIONAL THEOLOGICAL CONFERENCE

On November 18, 2010, the last day of the 4th International Theological Conference of the Russian Orthodox Church on Life in Christ: Christian Ethics, Ascetic Tradition of the Church and Modern Challenges, a round-table talk was held at the Department for External Church Relations Metropolitan Hilarion of Volokolamsk to discuss common Orthodox witness. Metropolitan Hilarion chaired the meeting and presented the following paper on the Importance of Monasticism for Orthodoxy Today:

Introduction:

Be perfect, therefore, as your heavenly Father is perfect (Mt. 5:48). Obedient to her Divine Founder, the Church of Christ has sought for almost 2000 years to attain what cannot be attained without the grace of God’s ideal of perfection given by the Lord in his Sermon on the Mount and underlying the great Christian ascetic tradition. This tradition, which has produced a great assembly of holy ascetics, did not appear overnight but became a fruit of ages-long development and refinement of its forms and norms. The progressive nature in which the ascetic tradition developed is attested to in the passage of the Gospel in which the Lord, relieving his disciples from some traditional forms of asceticism during his ministry on earth, points to the time when the bridegroom will be taken from them; then they will fast (Mt. 9:15). It is equally doubtless that the typology of Christian asceticism is rooted in the pre-Christian religious culture and not only in that of the Old Testament. In some sense, we can speak about one typology of asceticism built on some common human religious experience.

The specifics of Christian asceticism probably need to be found precisely in a synthesis of various ascetical traditions of religious and religious-philosophical origin – the synthesis which became possible through the closeness between the biblical idea of the image of God in man and the idea of becoming like God voiced in the Platonic religious-philosophical tradition.[1] The ascetic theology emerging at the junction of doctrine and ascetical practice is strongly dependent also on anthropology as it acquires a particular overtone depending on the tradition of thinking standing behind the anthropological views of a particular author (biblical, Stoic or Platonic). Even the very notion of ascesis, let alone other borrowings, goes back to a great extent to the Stoic favourite theme of ἄσκησις ἀρετῆς (‘exercise in virtue’), though in its origin it belongs to the sphere of gymnastics.[2]

This paper, however, is not about the theory of Christian ascesis, nor is it about the history of ascetical teachings but about the importance that the church estate – for which ascesis is a principal way of life, one can say ‘profession’ – has for Orthodoxy today. I mean monasticism.

But before moving to the discussion of this special matter, I would like to dwell on three fundamental points characteristic of Christian asceticism in essence, whatever the age or estate in which and by which it is exercised. First of all, every manifestation of asceticism in the Church is subject to the aim of bringing people closer to God, making them like God, training our nature for virtue and preparing it for a meeting with God which takes place, according to the economy of our salvation, in Jesus Christ. Thus, any manifestation of asceticism in Christianity cannot be viewed as an aim in itself or self-value (as, say, the ideal of passionlessness – ἀπάθεια in Stoicism) but it is to be viewed only as a means, as μέθοδος, and using this means, endless generations of Christians transform through God’s grace the human nature with its inclination to evil to become the beneficial vessels of the Word (Gradual, Tone 6).

Secondly, ascesis, not being an aim in itself, is at the same time an integral part and invariable companion of spiritual life as it affects equally the physical and spiritual spheres. The basic opposition in Christian ascetical tradition is not between body and spirit, not between the material and the immaterial as it is in various dualistic systems (Platonism, Manichaeism, some trends of Gnosticism, etc.) but between life according to the flesh (κατὰ σάρκα) and life according to the spirit (cf. Rom. 8:1-8off). While a life according to the flesh implies the imposition on oneself of some restrictions out of fear of punishment and is furnished with a system of bans (do not murder, to not commit adultery, do not desire… etc.), a life according to the spirit implies an inner urge for perfection in God motivated by the love of Him. In this context, every form of ascesis acquires a positive and creative meaning, not restricting one’s freedom according to the flesh but offering the ways of finding true freedom according to the spirit, tested by thousands of experiences.

And the third point stems from the first and second ones: it is the purely individual nature of ascetic work defining the measure of accomplishment considering the spiritual need of the individual in his growth into the whole measure of the fullness of Christ. (Eph. 4:13). The point is not absolute independence of Christians from one another in their ascetical practice, as it is impossible to hand down the living experience of the Church, which is the Tradition proper, Παράδοσις, without teaching and discipleship, without St. Paul’s I urge you to imitate me as I imitate Christ (1 Cor. 2:16). The point is that any ascetical norm, be it abstention in all its manifestations, the work of prayer both in public and in private or accomplishments reflected in monastic vows, is positive only if related to the general dynamic of a Christian’s spiritual growth and his acquirement of the mind of Christ (1 cor. 2:16) and his adoption of the main law of Christian life – the law of love.[3] This dilemma is pointed in Christ’s parable about ten maidens in which interpreters, beginning from Chrysostom, clearly see oil as mercy or love of men, that is, effective Christian love. Without attaining it, an ascetic, even if he has reached great ascetic heights, remains only a resounding gong or a clanging cymbal (1 Cor. 13:1).

Paradoxically, the same law of love making up the central pivot in the life of one church organism consolidates at certain times the ascetic work of individual members of this body into one devotional or ascetic burst aimed to oppose a certain spiritual or even material threat, like the mobilization of all vital resources that takes place in a human body struggling with an illness or in face of a threat. It is precisely how the present order of long and short fasts has been formed. This is how the Church fullness normally reacted to various dangers and disasters. This is how people impelled God and his saints towards mercy and beneficial help at the hardest moments of history. It is in this vein that we should consider the emergence of various monastic rules which used to gather together their followers into a brotherhood strong spiritually precisely in their unity and solidarity.

At this point we have come close to the main part of the paper in which we will speak about monasticism as the highest state of Christian perfection and a ministry of the Church and about some problems of monasticism today.

Monasticism as the highest stage in Christian perfection

The only goal of Christian growth is the mysterious meeting with God and entering into communion with God. There are different ways however that lead to this height. One of them, more gentle and long, is marriage, while the other, more steep and short, is monasticism. The life of the Baptist and some of the apostles of Christ, as well as some episodes from the Gospel and letters of St. Paul, suggest a possibility for an early achievement of this goal in celibacy. Indeed, the ministry of the Saviour on earth, too, could be carried out only if it was free from everyday family chores. During the taking of monastic vows, the Gospel is read, made up of two passages which contain the whole ‘philosophy’ of monastic life:

Anyone who loves their father or mother more than me is not worthy of me; anyone who loves their son or daughter more than me is not worthy of me. Whoever does not take up their cross and follow me is not worthy of me… Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you and learn from me, for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls. For my yoke is easy and my burden is light (Mt. 10:37-38; 11:28-30).

The desire ‘to be perfect’ includes the condition that one should ‘give all his possessions to the poor and then follow Me’ (cf. Mt. 19:16-22). Each Christian is called to a life of virtue but only a monk is obliged to seek perfection with all his heart. Each Christian is called to live according to the Gospel, but only a monk embodied the gospel’s ideal most radically by seeking to imitate Christ in everything. Each Christian gives in baptism a vow of faithfulness to God, but only a monk promises to God to follow the way of absolute non-possession, chastity and obedience. Each Christian is called to repent but only a monk’s lament should become a continued and everyday accomplishment. While the Lord commands a family man to be chaste in marriage, not to commit adultery, nor to look at women with desire, He demands from a monk to be absolutely lonely and to abstain absolutely from matrimony. While the Lord orders a layperson not to accumulate treasures on the earth but to be concerned in the first place for the Kingdom of God, a monk must reject every earthly possession altogether and have nothing of his own but give whatever is his own and his own self to God. While a lay person is commanded ‘not to love this world and whatever in the world’, a monk is called to reject the world fully and to hate it.

Therefore, monasticism appears to be the most radical form of following Christ’s call to perfection, selflessness and carrying the cross. Monasticism is a beneficial yoke of Christ, taken by a monk on himself voluntarily. It is the fullest imitation of the One Who is meek and humble in the heart and for Whom a monk gives up his parents, relatives and the entire world.

This yoke of Christ is expressed most clearly in the following vows pronounced by a person in the face of the Church before he or she assumes ‘the angelic image’:

to stay in a monastery and hold fast until the last breath;

to preserve oneself in virginity, chastity and reverence;

to obey the abbot and all the brethren in Christ;

to remain until death in non-possession and voluntary poverty in coenobitic life for the sake of Christ;

to accept all the rules of monastic life, the rules of holy fathers and orders of the abbot;

to be ready to endure every inconvenience and sorrow of the monastic life for the sake of the Heavenly Kingdom.[4]

One’s taking of these vows marks one’s entering a new life full of various feats and struggles.

The vow of virginity is not reduced to corporal chastity but also includes the protection of one’s thoughts and heart from impure feelings. ‘Chastity’ (Greek σωφροσύνη) means literarily ‘sanity’when one in all one’s actions and thoughts is guided by wisdom coming from above, which is Christ Himself – the Logos of God.

Non-possession means that one rejects any attempt to seek richness and temporal benefits. A monk possesses only that which is necessary for life, while giving the rest to the poor and being never attached to anything temporal so that his mind may be always free from any concern for things vain and temporal but be busy with the concern for the salvation of himself and his neighbours. ‘Steps’ and other monuments of ascetical writings speak of the virtue of pilgrim’s journey when a monk understands that there is no permanent city for him here, on the earth, and seeks a city to come because his spiritual homeland is the Heavenly Jerusalem, and it is to this city that his mental eye is directed.

Obedience has a special importance. It is the feat difficult to understand and accept for the modern man, while it constitutes the very essence of monastic work. Obedience lies in the basis of monasticism. Archimandrite Sophronius Sakharov, a great modern ascetic, writes: ‘Monasticism is first of all the purity of the mind. Without obedience, it is impossible to attain it, and for this reason, there is no monasticism without obedience. A disobedient person is not a monk in the true sense of this word. God’s great gifts including even the perfection of a martyr are quite possible outside monasticism as well, but the purity of the mind is a special gift given to monks, unknown on other paths, and this condition can be attained by a monk only through the feat of obedience’.

Obedience to a spiritually experienced guide helps or a monk understand the science of monasticism. Only the one who has passed this school can later become a guide for the next generation of monks.

‘Obedience is the grave of one’s own will and the resurrection of humbleness’, says St. John Climacus, ‘An obedient one, like a dead one, will not contradict or judge either in good things or what may seem evil to him; for the responsibility for everything is borne by the one who piously deadened his soul’.[5]

Prayer is the most important occupation of a monk, which supports him in observing the vows he has given; it is his spiritual weapon. For this reason, the monastic rules assign daily rounds of various prayers in church, in his cells, prayers common and individual. A monk, being constantly in prayer, should take communion as frequently as possible in order to become united with the divine nature of Christ and to live already here, on earth, the life of the age to come.

The inner mood of a monk should be closely bound up with repentance and lament. In the very beginning of his tonsure to the minor schema, the father superior, calling the tonsured one who has humbled himself down to the ground, says: Wise God as the Father Who loves his children, looking at your humbleness and sincere repentance, accepts you like a prodigal son who repents and comes to bow before him wholeheartedly.

A monk assumes the feat of repentance not because he is more sinful than other people but because he chooses repentance for himself as a way of life. St. Isaac the Syrian speaks of monasticism as the way of lament: The monk (Syr. abila, lit. ‘lamenting’) is he who, in hope for future blessings, spends all days of his life in hunger and thirst. The monk he who dwells outside of the world and always prays to God to give him future blessings. The treasure of a monk is consolation found in lament…[6]

In this continued grief a monk also finds a spiritual joy born from lament and repentance. In the chapter about ‘the joy-creating lament’, St. John Climacus says, Take effort to hold on the blissful and joyful sorrow of sacred tenderness and do not stop training yourself for this work until it puts you beyond all the earthly things and present you pure to Christ. He who clothed oneself in a blessed and beneficial lament as a conjugal vestment has learnt the spiritual laugh of the soul. Thinking about the ability of tenderness, I amaze at how lament and the so-called sorrow contain joy and merriment, like honey is contained in a cell… This tenderness is truly a gift of the Lord… because God gives consolation to those who grieve in the heart in a mysterious way.[7]

Consolation is sent down from God Himself Whom a monk serves by the whole of his life. Addressing a novice in the end of the tonsure, the father superior says: May all-generous God accept and embrace and protect and may that wall be firm in the face of an enemy…, lying down and standing up together with you, pleasing and cheering your heart with the consolation of His Holy Spirit.

Monasticism, unlike marriage, is a destiny of the chosen not in the sense that they are better than others but in the sense that they feel called and have taste for loneliness. If a person has no need to stay alone, if he is bored by being one on one with himself and with God, if he always needs something external to fill him, if he does not like to pray and is incapable of being engulfed in the element of prayer and coming closer to God through prayer, he should not take monastic vows.

In many respects it is much more difficult to live in the world. Monasticism is a ‘narrow path’ in the sense that one has to reject many things which belong to ordinary people by right. And monastics reject many external things for the sake of finding things internal. But I do not think that monasticism is higher than marriage or it is more conducive to the attainment of sanctity than marriage. Any path chosen by one, if one seeks God, is difficult because it is ‘a narrow door’. If one seeks to live according to the gospel, one will always encounter obstacles and will have to always surmount them. Monastic life, like a life in marriage, is given for one to realize one’s inner potential as fully as possible. It is given to find the Kingdom of God which can become a destiny for each of us after death, but we can partake of it by experience already here, on earth.

In the early Church, monasticism developed gradually. There were groups of ascetics who took the vow of celibacy. Some of them went to deserts, while other remained to live in cities. They set themselves as their principal aim to carry out spiritual work on themselves. This is what the Old Testament describes as ‘walking before God’ when the whole life of a person is directed to God, when every deed and word is devoted to God.

There is no contradiction between not only monasticism and marriage but also between monasticism and a life in the world. St. Isaac the Syrian says that ‘the world’ is a totality of passions. And a monk retreats from such a ‘world’, not the world as God’s creation, but the fallen and sinful world steeped in vices. He retreats not because he hates the world but because he disdains it, because outside the world he can accumulate in himself the spiritual potential which he will eventually realize in the service of people. St. Siluan of Mount Athos says, ‘Many accuse monks of wasting their bread, but the prayer they lift up for people is much more valuable than many things people do in the world for the benefit of their neighbours’.

St. Seraphim of Sarov said, ‘Seek the spirit of peace, and thousands around you will be saved’. Retreating to desert for five, ten, twenty and thirty years, hermits acquired ‘the spirit of peace’ – the inner peace which those who live in the world are lacking so much. But then they returned to people in order to share this peace with them. And really, thousands of people were saved around such ascetics. Of course, there were a great deal of ascetics who retreated from the world never to come back to it, who died in obscurity, but it does not mean that their feat was in vain, because the prayers they lifted up for their neighbours helped many. Having attained sanctity, they became intercessors and protectors for thousands who were saved by their prayers.

Monasticism as a church ministry

In this relationship between monasticism and the Church we begin to discern a special importance of monasticism for the whole Body of the Church along with other church ministries. It has turned out that a monk does not choose the thorny path full of temptation for his own sake. The spiritual richness he has accumulated will nourish dozens, hundreds and thousands of people, thus building the Body of Christ not only through sacraments and instruction as it is done in the ministry of Priesthood but through the example of the whole life of a monk who dedicates himself wholly to the service of God and people.

A testimony to this is the very monastic tonsure which is commonly ranked among the rites, though early church authors (Dionysius the Areopagite, Theodore the Studite) called them sacraments and included them in the list of other essential church mysteries.

Indeed, the initiation to monasticism is a grace-giving and mysterious beginning of a new life of a person in his service of the Church. There are some analogies with other sacraments, Baptism, Priesthood, Marriage and even Chrismation. The first and the closest analogy is that tonsure culminates in the partaking of the Holy Mysteries of Christ, thus being filled with grace. A person taking monastic vows is given forgiveness for all the sins he committed before; he renounces his former life and pronounces vows of faithfulness to Christ; he throws off his secular clothes to be clothed in a new vestment. Being born anew, he voluntarily becomes an infant in order to attain into the whole measure of the age of Christ (Eph. 4:13).

The tonsure takes place in the midst of the community and for the community which is the image of the whole Church of Christ. In this respect, the first question asked by the farther superior is characteristic: Have you come, brother, bowing before the holy altar and before this holy community? (that is, before a concrete monastic community?).

A new member’s entry into a brotherhood involves a new name to be given to him. The customs of changing one’s name in taking monastic vows is very old, going back in its essence to the Old Testament custom of one’s changing the name as a token of obedience (2 Kings 23:34; 24:17). From the moment of tonsure, the life of a monk does not belong to him; it belongs to God and to His Holy Church (in the person of the community). A monk is voluntarily cut off from his own will, which steps back before the will of God and the will of the church supreme authorities (in the person of the father superior). The rejection of all that belongs to him in favour of things common is another manifestation of the fullness of the gospel’s ideal embodied in the monastic community.

Assuming monasticism, a person assumes the responsibility not only before himself but also before those who will look to him, trying to find in him spiritual support. St. Isaac the Syrian says, A monk in the whole of his image and in all his deeds should be an edifying model for everyone who sees him so that, because of his virtues shining forth like rays, even the enemies of the truth looking at him may even involuntarily admit that Christians have a firm and unshakable hope for salvation… For monastic life is a praise of the Church of Christ.

The life of a monk does not belong to him but to God and the Church. A monk justifies his calling only if his life brings forth fruits for both God and the Church. A monk is beneficial for God if he continually works on himself and, progressing spiritually, comes ‘from strength to strength’. He is beneficial for the Church if he conveys to people the spiritual experience he has gained or is gaining to share it eventually with the weak members of the Church or simply to pray for people.

The monastic task is to listen attentively to the will of God and to bring one’s own will as close as possible to the will of God. A monk is the one who voluntarily abandons his own will, putting all his life in the hands of God. The communication of God’s will to church members, whether it is done verbally and individually or through the example of the life of a monastic community in the spirit of brotherly love and peace of Christ, is the fulfilment of the prophetic ministry in the Church.

Choosing only few Christians to carry out this ministry and calling them to live a special life, the Lord through them and in them maintains His Church in sanctity, soundness, meekness and love. If all the disciples of Christ are called to be the salt of the earth, if this world still stands thanks to Christians,[8] monasticism represents the salt of Christianity, the quintessence of the Gospel’s way of thinking which does not allow Christianity to be demoralized and to yield to the pernicious impact of the surrounding world.

On some problems of modern monasticism

In this ecclesiological dimension of monasticism, those who embark on this path bear a great responsibility since it is responsibility before the whole Church. Truly blessed is the monk who manifests to people the beauty and magnificence of life in Christ, and woe be to the monk whose way of life serves as a temptation for the faithful.

According to the Church Tradition, monastic vows are taken by one once and for all, and according to the canonical rules of the Church, even the monk who has taken off his monastic vestments and married continues to be regarded as monk but a monk who has fallen and who lives in sin. In this sense, monastic vows place on a person the obligations which are even greater than marital vows. The Church can recognize a marriage as invalid for a number of reasons and she even gives her blessing to the innocent party to inter into a new marriage, but no ‘dis-tonsure’ is recognized by the church canons.

Monasticism cannot take place as a sacrament of the church and as a church ministry if a person takes monastic vows against his will and out of obedience to another person or in too early an age out of one’s folly or under the influence of the mood or enthusiasm which will pass later to leave the person before the choice of whether to return to the world or become a bad monk when you remain such only not to violate the vows while feeling no joy or inspiration but feeling ‘chained to the oar’ and cursing your fate.

In Russian monasticism today, this happens because of the two serious failures: a rash decision to take monastic vows or absence of teachers experienced in spiritual work.

The examples I have encountered in my life have reaffirmed my conviction that the decision on tonsure can be made only after a very sober and serious reflection, only after one has been profoundly strengthened in his desire to live a monastic life and only after one has become sure that it is one’s calling from God, only one has been tested by a long temptation. As long as one has even a shadow of doubt, one should not assume monasticism. The error can have fateful consequences because, after taking monastic vows and then realizing that monasticism is beyond one’s power, one is seldom capable of returning to a normal life. He remains spiritually traumatized and morally maimed to the rest of his life.

On the monastic path, just as in a marriage, there may be ups and downs. The initial admiration at monastic life tends to be replaced by disappointment and habit. To survive these hard times a monk needs only an experienced spiritual teacher who himself was tempted and able to help those who are being tempted (Heb. 2:18). The power of monasticism lies precisely in the succession of spiritual guidance which, like the apostolic succession, comes from the early Christian times as spiritual experience has been handed down from a teacher to a disciple and then the disciple himself becomes a teacher who will hand down his experience to his own disciples.

In the history of Christian sanctity, there are great many examples when monastic experience was handed down from a teacher to a disciple. St. Simeon the New Theologian was a disciple of St. Simeon the Righteous. Having received from his teacher profound knowledge of ascetical and mystical life, he wrote it down and handed it down to his own disciples. Nicetas Stephatus, who wrote ‘The Life’ of Simeon the New Theologian, was his closest disciple. And naturally Nicetas Stephatus himself had disciples. The uninterrupted chain in the succession of spiritual experience has continued from old times to our day. Even in the Soviet time this chain was not broken in the Russian Orthodox Church, though it was weakened since spiritually experienced guides, starets, were a great rarity at the time but they still existed.

Today the number of monasteries in the Russian Orthodox Church has exceeded 800, but not every one of them can boast of having a spiritually experienced teacher. It is understandable, since it takes decades for spiritual leader to grow and for them to grow, there must be a lasting monastic tradition. Spiritual directors themselves must be disciples of experienced teachers. And what can a young abbot teach equally young monks unaccustomed to obedience if he himself has not been through a long school of obedience?

A way out of this situation may be as follows: just as in antiquity, people of the conscious age were not baptized without due catechization and were not tonsured until they reached spiritual maturity, a person should undergo a long preparation before taking monastic vows. Tonsure should become not the beginning of a monastic life but a certain result of a long temptation as it should reconfirm that a person is ready for monasticism, that his desire to become a monk was not hasty and that it was his own desire, not that of another person who tried to coerce him into monasticism.

The establishment of a monastery should involve the availability of a spiritually experienced leader. It should not be a situation in which such-and-such nun is assigned to act as abbess with ‘a cross placed on her as befits her office’ only because the monastery is standing there but there is no one else who can lead it. A monastery should be opened because there is an experienced spiritual guide around whom a new brotherhood has gathered.

Deeply rooted spiritual work and the feat of obedience to which a monk is called can help to heal another widely-spread illness of today’s monasticism – the ardour for condemning so uncharacteristic of monasticism. Without having an adequate theological training or a spiritual vision of the essence of church problems, monks begin to present their own inventions as the voice of the Church, coming into confrontation with the supreme church authorities. The voice of monastic communities can be considered the voice of the Church only if it sounds in unison with the voice of the supreme church authorities.

The practice of early ordination of monks to priesthood with granting them broad powers of spiritual guidance is senseless. Before they become strong in the struggle with their own thoughts, before they have learnt genuine obedience and humbleness, young ‘starets’ begin to subdue those who come to them, involving themselves in every twist and turn of their lives. It is appropriate to remind them of the word of the Saviour: You hypocrite, first take the plank out of your own eye, and then you will see clearly to remove the speck from your brother’s eye (Mt. 7:5).

It appears more reasonable to use the practice of the Athonite monasteries in which the number priest-monks in a monastery is very limited, while most of the brethren live all their monastery life as ordinary monks who fulfil the most important tasks in the monastery. Among such was St. Siluan of Mount Athos, who was a long-standing economic father of St. Panteleimon’s Monastery without being ordained to priesthood. And the present Administrator of the Holy Mount has no priestly rank. He wears a small cross and holds the Administrator’s staff as befits his office and is called ‘starets’ only in respect for his age.

There is a special stratum among the monastics who have to live outside the monastery walls due to their line of work or in obedience to the supreme authorities. These are parish priest-monks, teachers at theological schools, staff of diocesan and Synodal departments. Their monastic path is especially difficult, for their task is to turn their ordinary home into a monastic cell, while the surrounding world with all its temptations should become a desert for them. For them, monasticism is first of all a path of inner work, and they cannot always rely on their spiritual guide. But if they always look at the image of Christ and do not miss opportunities for retreat and prayer and for being nourished by the spiritual meal of holy fathers and teachers of asceticism, they can well establish themselves as monastics. A serious blunder is made by those who assume tonsure for the sake of church career. In the modern practice of the Russian Orthodox Church, only a monk can become a bishop. This leads to the situation where people with career aspirations assume monasticism to reach the church heights. But only few reach these heights because there are many monks but few bishops. Monasticism can be assumed only if a person is wholly oriented toward God and is ready to give his life to God and to go through the narrow door. Monasticism is the utter expression of this ‘narrow’ path about which the Lord says in Mt. 7:13 and Lk. 13:24. It is a path of reaching the inner heights, the path of internal findings with external losses. But the assumption of tonsure for the sake of career corrupts the very essence of monasticism.

It is inadmissible to assume monasticism in obedience. Regrettably, often a person at some stage of his life cannot decide whether he should take up monasticism or enter into a marriage. Lacking his own inner power to make an independent decision, he goes to starets for an answer. This approach is vicious. A person should make every important decision himself or herself and to appeal to starets only for a blessing for the implementation of this decision.

Conclusion

The first Christian martyrs were ready to die for the name of Christ, wishing to imitate Him in everything up to accepting death.[9] They became the first saints to be venerated by the Church for their uncompromising stand and faithfulness to Christ. After the persecution was over, it was bloodless martyrs – hermits who escaped from the world to serve God alone – who became the ardent fulfillers of the Gospel. The opposition between the monastic way and the Church was overcome in history since the Church realized the importance of monasticism while monastics sought to dedicate themselves to the Church. In the Orthodox awareness imbued as it is with symbolism and imagery, monastic communities always remain an image of the Church in which it is possible to this day to realize the early Christian ideal in which everything is in common possession and every one occupies his or her own place and obedience is filled with mutual love between the one who orders and the one who fulfils the order, in which tears bring joy in the Holy Spirit, in which Christ is present in every sigh and every thought of a monastic.

Monasticism is called to carry out a special ministry in the Church. But this ministry can be realized only if monasticism becomes a way of perfection and transformation of a person’s life, changing it in the most radical way. Monasticism which wishes to become truly ecclesiastical is subject to the words said by Christ about Himself: Unless a kernel of wheat falls to the ground and dies, it remains only a single seed. But if it dies, it produces many seeds (Jn. 12:24). In imitation of Christ, a monk follows the way of extreme exhaustion in order to serve the neighbour as far as possible so that he may lay down his life for his friends (Jn. 15:13) and that the devil in his heart may be defeated.

Monasticism remains today an integral part of church life. A great deal of the most difficult and necessary church tasks are fulfilled by monks and nuns. But monasticism becomes a true sacrament of the Church only if it overcomes all the dangers that lie in wait for it in the present era.

At a time when Christianity is attacked by the godless world, when young souls are overwhelmed with doubts because they do not have any support from the customs of devotion, the sanctity and purity of monastic life should become a beacon that will direct all those who swim in the sea of life, both those who are in the Church and who are yet coming to her. For this a monk needs to hear the voice of God and to dedicate his whole self to God. For this he has to come to hate himself and to love his enemy. For this he needs to purify his heart and give Christ Himself an opportunity to work in it. Following this way, monasticism will render a priceless service to the whole Church of Christ.

[1] This closeness was effected in the depth of the Alexandrian theology beginning from Philo to Origen. See, Festugiere P. Divinisation du chrétien // Vie Spirituelle. 1939; J. Daniélou «La mystique d’Origène» // Daniélou J. Origène. P., 1948. P. 287

[2] St. Paul himself repeatedly conveys the reality of spiritual life through sports metaphors of running (δρόμος) and wrestling (ἀγών) (Gal. 2: 2; Phil. 2:16; 2 Tim. 4:7). However, he uses the verb ἀσκέω in some trite meaning ‘to train oneself, to try (to do something)’ as it is conveyed by the author of the Acts, only ones in his apology to Lysias (Act. 24:16).

[3] Cf. also 1 Tim 4:7-8 ‘Train yourself to be godly. For physical training is of some value, but godliness has value for all things, holding promise for both the present life and the life to come’.

[4] The rite of tonsure in a minor schema

[5] That is to say, the one he obeys

[6] Прп. Исаак Сирин. Слово 58 (309). Слова Подвижнические. СПб., 1911. С. 309.

[7] Прп. Иоанн Лествичник. Лествица 7, 9; 7, 40; 7, 49.

[8] Letter to Diognetus, 5

[9] Holy Martyr Ignatius the God-Bearer. To the Romans 7.

Day in the life of an Orthodox monastery

A Day in the life of a Catholic monastery

Quaerere Dominum (Catholic)

No comments:

Post a Comment