WHAT DO WE WANT OUR MONASTERY CHURCH TO LOOK LIKE?

|

| the abbey of Chevetogne where the truth of icons meets the truth of the Catholic Church |

Soon we shall have the exciting task of deciding what kind of church we are going to have in Pachacamac. Although we have not yet got down to any form of systematic discussion, there are certain decisions that have already been made. The first is that it is going to be a traditional rather than a modern church. The second is that we are going to use icons. Let us examine these decisions.

Le Corbusier said that a house is a machine for living in: its design should have its function in mind. It should be so designed that living in it should be made as easy and as pleasant as possible. Living in it is what a house is for: anything that contributes to this aim is to be included in the architecture; anything that makes living in it difficult or unpleasant must be excluded as far as possible.

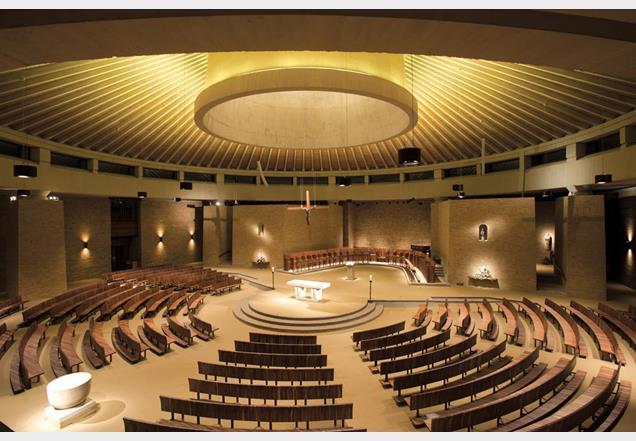

When applied to a church building, the interior is transformed. We all know the argument: the real church is the community gathered round their priest in the celebration of the Eucharist; the building is merely giving the real church shelter. Anything that makes it easy for the local church to realise that it is the Church, the body of Christ, must be included; anything that obscures this truth must be excluded. The result? Something like this:

What is wrong with that? Is that not a good argument for having a church built in that style? How can we be true to Vatican II and NOT build in that style?

A modern church is built on the idea of its liturgical function, at least as far as the Church is concerned: and this means celebrant, concelebrants, deacons and people, all acting in harmony in such a way that they experience themselves to be one Church.

Hence, as a house is a machine to live in, so a church is a machine in which to celebrate the liturgy. Where does it go wrong? If you compare this governing idea with that which built the byzantine or gothic churches, you will immediately notice the flaw. While the modern church concentrates on the visible functions in the liturgy, the external performance of the rite, the byzantine and gothic churches concentrate on the vision of those who participate in the liturgy and see the functions of the liturgy in that context. Traditional churches express both the function and the ecclesial vision of the Church that celebrates. St Francis of Assisi says that while those with faith see and believe, those without faith only see. Churches are about what we know by faith, and not only about what is visible. Byzantine and gothic churches, as well as the wonderful baroque churches built by the Jesuits and friars in Mexico and other countries in Latin America, express, not only what is visible in Christianity, but the whole faith, the whole meaning of the Catholic Church's liturgy which embraces the invisible. St John Chrysostom says that the sanctuary is filled with angels during the celebration. If their presence is not suggested by the architecture, then there is something inadequate with that architecture.

The Catholic Church is a sacramental church, where the visible expresses and makes available and even allows us to touch and make our own what is beyond the grasp of our imagination. By participating in the Church's liturgical life, we share in the life of the Holy Trinity in such a way as to make heaven and earth different dimensions of a single interlocking reality. We can picture our participating in the liturgical life of the Church that embraces heaven and earth by using icons that Eastern Christianity has preserved for us or by being bathed in the light that comes from gothic windows: we can only worship in wonder as we share in the very life of God himself.

Liturgical art must point towards the inexpressable even when we leave concepts and logic behind. That liturgy leads us from what can be immediately and easily portrayed in word and gesture into a dimension that only love can reach, and this was taken for granted in traditional Catholicity because it is the very core of Catholicity and received artistic expression in traditional church architecture, which is why we choose to build a monastery church according to a traditional plan rather than to a modern plan. Modern church architecture encourages a secularised vision that embraces only the visible functions and relationships of those who participate in the liturgy while it ignores the Vatican II approach in which the earthly liturgy permits us to share in the heavenly liturgy, as shown in the Letter to the Hebrews and the Apocalypse and so clearly expressed in Sacrosanctum Concilium, the Vatican II constitution on the liturgy in its very first chapter.

Am I suggesting that churches built in a modern style should be knocked down, and traditional churches be built in their place? No, because the principle upon which they are built is authentically Christian, even though it is not complete enough to express the Christian vision. I chose a photo of Worth Abbey because I found it particularly imposing and noble, and there is no doubt that you are in a church; and many modern churches like this one can house splendid modern Masses which are very much centred on God rather than man. Moreover, there exist modern churches that have not left the Christian vision. Here is an example:

However, I must insist that, while I believe that the functional principal is a good principle to build on, it is not enough. I hope I have demonstrated that, in a liturgical building, the functional model is inadequate because the Catholic liturgy is more than functional and introduces us into a Reality far greater than itself, something a church building should help us to envisage.

What I propose is, at least for me, rather exciting: modern churches should be looked at again, and those who have a more adequate understanding of liturgy should ask themselves what is to be done to the church, artistically speaking, to allow it to reflect the invisible as well as the visible, heaven as well as earth. As those who understand icons will acknowledge, there is something in common between icons and windows, which is why we are using icons in Pachacamac, but the fact that icons and windows are also different from one another implies that those who seek to be authentically traditionalist are not condemned only to endless repetition. Let those who wish to make these modern churches more adequate for their purpose try to discover solutions that blend in with their architecture. This will be a challenge indeed; but, until this is done, we shall continue to choose a traditional plan over a modern one for our monastery church.

A TRADITIONAL CHURCH IN THE ORTHODOX EAST

Why We Need to Take Our Children to Liturgy

Have you ever found yourself remembering a place while you think? I remember the first time I noticed this habit in myself. In 7th grade, I went to my mom, also an avid reader, one night after finishing an assigned book. “Mom, I just realized something. This entire book seems to be overlaid in my mind with the bus route through my friend’s neighborhood.” She related to the experience, but we didn’t know what to call it. Fast forward a couple of decades, and I found out that there’s a name for this sort of thing: memory palaces.

Keeping track of stories through memories of places is so effective that the world’s best memory champions use the technique to win competitions. The practice is simple: think of a place with which you are very familiar. Imagine yourself in it, and imagine a prompt to what you’d like to remember. For instance, if I wanted to remember the day my daughter was baptized, I might imagine myself by the font in church, along with a plaque reading 711. This would remind me that she was baptized on July 11.

But the practice also extends to larger thought patterns. Remembering a long story, a poem, a group of names, prayers, an entire book of the Bible, can all be helped along with the memory palace technique. It can even be used to sort out ideas that haven’t happened yet, to help solve problems or match prayers to needs.

Memory palaces were common tools in the early and medieval Church. Scholars, teachers, and preachers used the method to memorize the scriptures, long sermons, and even the traditional teachings passed down through the fathers. The remarkably universal faith was spread not only by letters, but also by the trained memories of Christians. St. Augustine devotes several pages of the “Memory” section of his Confessions to describe the practice of recalling memories. Memory can be trained not only to remember the past, but to envision the future. Simply put, we can picture what we’re going to do before we do it. God can also work on our memories, not only by giving visions, but also by shaping the memories. We don’t worship things we see or imagine, but they can point us toward God. Our memories can become God-shaped, in the sense that everything we have experienced in life can point us toward God.

As St. Augustine reminds us, these interactions take place in the “palaces and fields of our memories,” the places with which we are familiar. The more familiar we are with a place, the more layers of memories we can imagine there. The transformation of memories into holy memory happens – you might have guessed – in Eucharist, giving thanks.

Now, take a moment to think of the places that shape your daily life. Your home, your kitchen, your walks, the church… What if you tried to remember in the church building? What if the place of Eucharist was the place that your memory was trained around? Think of the solace and hope if you recall the memories of a loved one alongside the icon of the Resurrection. How would your vision of the future change if the Theotokos were before your eyes? If you struggle with a passion, examine your soul beside St. George slaying the dragon. What courage to remember alongside Archangel Michael with his spear in the devil!

Since you cannot be alone in the Church, your memories would also include your fellow Christians. Imagine praying for a light to shine in your despair or a person with whom to share joy, and recalling the parishioners who usually stand just there beside you. What would your memories smell like if incense filled them? How would the memory of harsh words sound with the choir singing over them?

This week, as we celebrate St. Barbara, patron saint of architects, I began to think of how all of us, and especially our children, are formed by the places around us. A holy place, shaped around the Remembering of God, is a sacred gift. We want our Church to be our children’s memory palaces, as well as our own. The gift of familiarity is granted through repetition. Our minds can only be formed by the Church and church buildings when we gather regularly. It’s not always easy to bring children to church. But it will be a far harder life for them if we neglect the shaping of their memories.

Going to church gives our children the space to lift their memories, with their hearts, toward the Lord. Supposing they grow familiar enough that their minds take on the shape of the Liturgy. Perhaps then they will be ready to say, when the time comes, “Remember me when you come into Your kingdom.”

A TRADITIONAL CHURCH IN THE CATHOLIC WEST

The Gothic Cathedral: Height, Light, and Color

Overview

The Gothic cathedral was one of the most awe-inspiring achievements of medieval technology. Architects and engineers built churches from skeletal stone ribs composed of pointed arches, ribbed vaults, and flying buttresses to create soaring vertical interiors, colorful windows, and an environment celebrating the mystery and sacred nature of light. Based on empirical technology, the medieval cathedral provided the Middle Ages with an impressive house of worship, a community center, a symbol of religious and civic pride, and a constant reminder of the power and presence of God and the church.

Background

The growing impact and power of the Christian church in western Europe after the fall of Rome in 400 influenced church architecture. In Mediterranean Europe where sunny skies and hot summer days mandated buildings with small window space and thick walls, the Romanesque style dominated church architecture. However, in the northern and western regions of the continent, cloudy days and less intense summer heat were common so designers developed a style that attempted to maximize interior light and uninterrupted interior heights. Architects sought a style that would provide larger windows to illuminate the buildings' interiors. Because a cathedral nave flooded with light would have a dramatic effect on the faithful, vast window space became a necessary characteristic of the Gothic style and responded to one of the goals of a growing and dominant religion in the medieval era.

The Crusades also affected the development of the Gothic style. Crusaders returning from the Holy Land brought with them many relics, and church fathers wanted to display these holy objects prominently. Devout Christians often undertook several pilgrimages in a lifetime; because hordes of pilgrims paid homage to these relics the numbers of worshipers entering those churches increased intensifying the need for a greater amount of interior light and space.

The use of light as a factor in worship and in understanding the mystical paralleled another chief goal of the medieval cathedral builder: the pursuit of greater and greater interior heights. At a time when religion dominated everyday life and when the faithful spent an average of three days a week at a worship service, church leaders sought an architectural style which created a sense of awe, a sense of the majesty and power of God for anyone who entered the church. Waging a constant battle against gravity, master masons, who both designed and built these cathedrals, wanted to create as much uninterrupted vertical space as possible in their stone structures. These soaring heights provided a dramatic interior which served to reinforce the power of the church.

Medieval master masons used three architectural devices to create the Gothic style: the pointed arch, the ribbed vault, and the flying buttress. The pointed arch, a style that diffused to the West from the Arabic world, permitted the use of slender columns and high, large open archways. These stone arches were essential in the resultant stone bays that provided the basic support system for a Gothic cathedral freeing the area between arches from supporting the building. For the church's interior, these "curtain walls" added to the delicacy, openness, light and verticality of the space. The curtain walls on the building's exterior were filled with glass, often stained or colored glass, conveying some biblical or other sacred tales.

The use of ribbed vaults for cathedral ceilings complemented the pointed arch as an architectural element. By carrying the theme of slender stone members from the floor through the ceiling, ribbed vaults reinforced the sense of height and lightness in the building. In a visual and structural sense, these vaults connected several stone columns throughout the building, emphasizing the interconnected stone elements which produced a skeletal frame that was both visually dramatic and structurally elegant.

The flying buttress completed the trio of unique Gothic design elements. In essence, this kind of buttress, typically used on the exterior of a church, supplemented the structural strength of the building by transferring the weight of the roof away from the walls onto these exterior elements surrounding the edifice. Often added as a means of addressing a problem of cracking walls in an existing building, these buttresses were incorporated so artfully into the exterior design of the cathedral that they became a hallmark of the Gothic style. By freeing the walls from supporting much of the weight of the cathedral roof, the flying buttress allowed medieval architects to pursue their goal of reaching ever greater interior heights.

The combination of these new architectural elements, which defined the Gothic style, along with the Church's interest in increased interior light, space, and height, resulted in a new technology heavily influenced by religion. Religion's goals provided the impetus for a daring empirical technology; at the same time, technological methods allowed the church to achieve an innovative awe-inspiring space within a new architectural style.

Impact

|

| St - Denis |

The Abbot Suger of St.-Denis near Paris first promoted the Gothic style in medieval France. As the leading French cleric of his time, Suger headed the mother church of St. Denis with its strong ties to the French crown. When he sought to transform that church into an impressive center for pilgrimages and royal worship, he turned to the emerging Gothic style. Gothic elements would allow him to create a building with soaring heights, with curtain walls to fill with stories and lessons in glass, and with a display of light used to represent mystery and divinity. For Suger, the Gothic style created a transcendental aura, a theology of light and he hailed it as "[the]ecclesiastical architecture for the Medieval world." Suger's architectural preferences spread throughout France so effectively that the country became home to the most impressive and successful Gothic cathedrals. His notion that architecture could serve as theology appealed to the Church with its great influence over a mass of illiterate believers. The Gothic cathedral became a huge edifice of stories, signs, and symbols filled with church teachings and lessons for any who passed by or entered these churches. For many people of the Middle Ages, the cathedral became the poor man's Bible.

The cathedral itself was a citadel of symbols. The orientation of the building usually positioned the altar facing east toward the Holy Land with the floor plan in the shape of a cross. Exteriors contained sculptural elements representing both sacred and secular themes. A depiction of the Last Judgment often adorned the west portal so all who entered were reminded of their ultimate fate. Usually, the west portal also consisted of three entryways to mirror the doctrine of the Trinity. Interiors contained rose and other stained glass windows with the same mix of the sacred and the secular scenes present on the exterior. Rose windows themselves served as representations of infinity, unity, perfection, and the central role of Christ and the Virgin Mary in the life of the Church. The interplay of geometry and light in rose windows and the special qualities of changing color tones and glowing window glass in all of the stained glass windows created a visual experience with mystical and magical qualities that transported a viewer into a world far different from his or her mundane medieval surroundings. Sculptures within, along with paintings, tapestries, and geometric patterns in columns and walls, added to the teaching environment; inside a cathedral one could not escape being exposed to lessons or stories. Add to these the awe one felt by the great interior heights and the cathedral's impact was overwhelming, reinforcing the church's power and influence in the medieval world.

In addition to its role as a center of church lessons, the cathedral served as a source of community pride. Often the largest structure in a city or town, the church served as community center, theater, concert hall, circus ring, and meeting place. The cathedral at Amiens in northern France, for example, could house the entire population of the city. Often sited on the highest point in a city or in the city center, the cathedral dominated the cityscape. With its soaring towers and spires it could be seen for miles around and became a symbol of a city much as skyscrapers or tall monuments define cities in modern society. Because the cathedral was a source of civic as well as religious pride, cities vied with each other to build the largest or the tallest churches. As a multi-purpose structure, the cathedral served as much more than a house of worship.

Anyone who visits an extant Gothic cathedral today quickly understands the impact it had on medieval life, religion, and technology. Just as religion dominated the era, the cathedrals themselves dominated, and continue to dominate, much of the landscape of western Europe leaving no question regarding the major force in people's lives.

For example, Gothic cathedrals commanded the physical landscape with interior and exterior heights not matched until the late nineteenth century. External central cathedral towers rising as high as 450 feet (137 m) and uninterrupted interior space of 130-160 feet (40-49 m) from floor to ceiling overwhelm modern visitors much as they did medieval worshipers centuries ago.

Because Christianity reigned over every aspect of medieval society, the sacred and the secular became intertwined so that a cathedral played, and continues to play, both ecclesiastical and civic roles. With so much interior space, it remains the center for many special occasions as well as regular church activities.

Likewise, the cathedral as a marvel of an empirical technology, using relatively simple tools and skilled craftsmen aided by a large labor force, remains an impressive example of the interaction of technology and religion. That linkage has had an impact so strong in the Western world that the Gothic style has become synonymous with church architecture. The neo-Gothic style appears in many churches, and even skyscrapers, built in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

Standing today as reminders of a historical era, the Gothic cathedrals provide insights into the power of religion, the achievements of technology, and the role of civic pride and responsibility. Their impact has endured over the centuries and continues to inspire awe in both the sacred and the secular worlds just as they did when these magnificent stone structures were first built in the Western world several centuries ago.

Further Reading

Courtenay, Lynn T. The Engineering of Gothic Cathedrals. Brookfield, VT: Ashgate Publishing, 1997.

Favier, Jean. The World of Chartres. New York: Harry N. Abrams Incorporated, 1990.

Gimpel, Jean. The Cathedral Builders. New York: Grove Press, 1983.

Johnson, Paul. British Cathedrals. New York: William Morrow & Company, 1980.

Morris, Richard. Cathedrals and Abbeys of England and Wales: The Building Church, 600-1540. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1979.

von Simson, Otto. The Gothic Cathedral: Origins of Gothic Architecture and the Medieval Concept of Order. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1974.

Swaan, Wim. The Gothic Cathedral. New York: Parklane, 1981.

Full Text: COPYRIGHT 2001 Gale Group, COPYRIGHT 2005 Gale.

Source Citation

"The Gothic Cathedral: Height, Light, and Color." Science and Its Times. Ed. Neil Schlager and Josh Lauer. Vol. 2. Detroit: Gale, 2001. World History in Context. Web. 14 Dec. 2015.

URL

http://ic.galegroup.com/ic/whic/ReferenceDetailsPage/ReferenceDetailsWindow?zid=eebcdbb0208e225653232dd368ecc6a1&action=2&catId=&documentId=GALE%7CCV2643450147&source=Bookmark&u=san66643&jsid=eb867a365f64a89c98bff2b0f3f2a36b

DON'T BLAME VATICAN II

MODERNISM AND MODERN CATHOLIC CHURCH ARCHITECTURE

by Randall B. Smith, appearing in Volume 13

my source: the Institute of Sacred Architecture

Many people seem to think that contemporary Catholic church architecture is so ugly because of misunderstandings that arose from the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council. This thesis is especially attractive to those of a more “intellectual” bent, such as theologians and liturgists, because it suggests that the problem is one of ideas. Correct the ideas—enforce a proper theology of the liturgy (the job of, guess who, theologians and liturgists)—and voilà, we will get better-looking churches.

Many people seem to think that contemporary Catholic church architecture is so ugly because of misunderstandings that arose from the liturgical reforms of the Second Vatican Council. This thesis is especially attractive to those of a more “intellectual” bent, such as theologians and liturgists, because it suggests that the problem is one of ideas. Correct the ideas—enforce a proper theology of the liturgy (the job of, guess who, theologians and liturgists)—and voilà, we will get better-looking churches.

As attractive as that thesis is, its one big drawback is that it is largely untrue. Bad church architecture is not primarily the result of bad ideas about the liturgy—however much those abound. No, bad church architecture in America is the result, quite simply, of America having bad ideas about architecture. Our problems began some decades before the Second Vatican Council convened: they began with the embrace of modernist architectural principles by contemporary architects and, more disastrously, by the liturgical “experts” who have insisted on laying down the rules and regulations for all new Catholic churches built in America.

An Illustration of the Problem: Speaking of Liturgical Architecture

A good example can be found in a small, but particularly illustrative little booklet published in 1952 by the Liturgy Program at the University of Notre Dame called Speaking of Liturgical Architecture.1 The author, one Fr. H. A. Reinhold, is described in the preface of the book as someone who “needs no introduction to American Catholic readers” because “he has become a household term [sic] in things liturgical.”2 And although the correct expression should probably be “he has become a household name in things liturgical,” the point is clear: he was a well-known and highly respected liturgist who can be said to represent the mind-set of his generation,3 —a mindset that continues to dominate much of the official thinking about church architecture to this day.

Although published in 1952, the lectures contained in Speaking of Liturgical Architecture were actually delivered several years earlier, during the summer of 1947, at “the first liturgical summer school at the University of Notre Dame.”4 Given that these lectures were delivered some fifteen years before the Second Vatican Council began, whatever faults Fr. Reinhold may be guilty of, it would be something of a stretch to blame them on the Council. And, although it is certainly true that Fr. Reinhold may have held in the 1940s and 1950s some of the same ideas that brought about the liturgical reforms of the Council, it is not primarily his ideas about liturgy that are the problem, it is his ideas about architecture. And those ideas are identifiably and undeniably modernist.

Form Follows Function: Functionalism and Modern Church Architecture

Take, for example, the most prominent principle of church design in Fr. Reinhold’s book. The point of publishing these lectures, according to the book’s foreword, was “to focus attention on some simple but basic liturgical requirements in the building and decoration of Catholic churches.” Indeed, this thesis is repeated throughout the book: namely, that the rules governing the building of churches must be derived from their liturgical function. “One thing it is safe to say,” says Fr. Reinhold, “[a church’s] liturgical, sacramental function ought to be the determining factor [in its design].” He expresses his approach to church architecture very clearly: “We are trying to find a principle for our procedure in the liturgy itself.” The title of the book, after all, is not Speaking of Church Architecture, but rather Speaking of Liturgical Architecture. What may at first seem like an innocent, even appropriate, principle of church architecture—design the church with the liturgy in mind—will become in the hands of Fr. Reinhold and his successors a means of forcing all churches to conform themselves to a fundamental principle of modernist design.

So it is that the first major, bold-faced heading in Fr. Reinhold’s text instructs the prospective liturgical “expert” (and church designer) that the most basic principle to be followed in building churches is not “respect the liturgy,” but “form follows function.” Indeed, Fr. Reinhold starts out his book with a chapter entitled “Functional Characteristics” and develops his entire conception of church architecture from this starting-point. The principles of “form follows function” and “functionalism” were, of course, two of the most basic principles of modernist architecture. And although Fr. Reinhold denies repeatedly throughout his book that he is favoring any particular “style” of architecture over any other, it is telling that he bases his entire discussion of church architecture on these fundamental modernist principles.

So what does “functionalism” entail? If one thought that “functionalism” meant that a building’s form (or structure) should facilitate a certain function (or practical activity), such as worshipping or doing business or drinking coffee, then one would be mistaken. Modernist buildings are not especially “functional” in that sense—as when Mies van der Rohe designed windows that made the occupants of his skyscrapers feel as though they were going to fall fifty stories down to the street and then forbade them to put anything in front of the windows to cushion the effect of the vertigo;5 or when Frank Lloyd Wright forbade the residents of his houses to move the furniture or even to put new pictures on any of the walls. So too modernist churches tend not to be “functional” in terms of the practical requirements of the liturgy; there may be, for example, no way for the priest to process in, no freedom to have statuary in the nave, and often no prominent crucifix at the front. Thus, contrary to what Fr. Reinhold says, it is not exactly the requirements of the liturgy that are governing the design of churches.

By the same token, if one thought that “form follows function” meant that a building’s function should be recognizable from its form, one would also be sadly mistaken. Indeed, one of the most characteristic features of modernist architecture is that it obliterated the differences among building “types.” Whereas we used to recognize a building from what it “looked like,” and we gave it a name because of its form—we called a certain building a “church” because it had the recognizable form of a church, another a “bank” because it had the form of a bank—now if we take the “bank” sign off the bank and put the “church” sign on it, then it becomes a church. In fact, often, if not for the sign, it would be hard to tell the difference.

Building from the Inside Out: Functionalism and the Principle of “Expressed Structure”

So if “functionalism” does not mean that a church should facilitate the function of a church, namely, the liturgy, and if “form follows function” does not mean that a church should have the identifiable form of a church, then what does it mean? We can perhaps best illustrate what Fr. Reinhold means by “functionalism” by simply turning to his book. What is interesting to note is that this book on “functional” church design does not begin by examining historical examples of buildings that have facilitated the liturgical celebration, nor does it begin with an analysis of the liturgical action itself in order to determine what sorts of structures might be needed. Fr. Reinhold instead immediately informs his reader that, since Baptism and the Eucharist are “the two most important sacraments” in the Church: “the prominence of these two sacraments must determine the architecture of a church, inside and out.” “A parish church,” he declares, “is above all a Eucharist ... and Baptism ... church. Its inside should express this. If its inside organs are thus disposed and visibly emphasized,” he says, “honest architecture (functionalism in its true sense) should manifest these two foci on the outside—in the right place.”

Now one could certainly quibble with this particular hierarchical view of the sacraments (and every person to whom I have explained Fr. Reinhold’s position has, and usually with some vehemence). Even if we granted—just for the sake of argument—that Baptism and the Eucharist were the two most important sacraments, it would not necessarily follow that this factor should determine the structure of the church building, both inside and out. It is not a principle one finds in the works of any of the great church architects of the past. So why has this become the absolutely essential principle of church architecture for Fr. Reinhold?

The answer, quite simply, is that it was an essential principle of architecture for architectural modernists. It is what they meant by “functionalism.” So, for example, The Columbia Encyclopedia, describes “functionalism” as follows:

Functionalist architects and artists design utilitarian structures in which the interior program dictates the outward form, without regard to such traditional devices as axial symmetry and classical proportions ... Functionalism was subsequently absorbed into the International style as one of its guiding principles.6

Indeed, it was the famous Swiss modernist architect Le Corbusier who instructed his disciples in his landmark book Towards a New Architecture that “The Plan is what determines everything” and that “The Plan proceeds from within to without; the exterior is the result of the interior.”7 This notion that “the interior program should dictate the outward form” is also known as “the principle of expressed structure.” In his best-selling book on modernist architecture, From Bauhaus to Our House, author Tom Wolfe explains:

Then there was [among the Modernists] the principle of “expressed structure.” ... Henceforth walls would be thin skins of glass or stucco ... Since walls were no longer used to support a building—steel and concrete or wooden skeletons now did that—it was “dishonest” to make walls look as chunky as a castle’s. The inner structure, the machine-made parts, the mechanical rectangles, the modern soul of the building, must be expressed on the outside, completely free of applied decoration.8

This is why Fr. Reinhold believes that, if the inside organs are visibly emphasized on the outside, this is “honest architecture (functionalism in its true sense).” The unexamined question, however, is whether all buildings must be built this way. The “principle of expressed structure” is merely presumed to be true. It has become by Fr. Reinhold’s time—at least in the circles he runs in—an unexamined, self-evident truth.

Using the Principle of “Expressed Structure” to Judge All Church Architecture of the Past

Indeed, this set of modernist principles and presuppositions seems to trump every other authority for Fr. Reinhold, even the authority of his own Church’s traditional heritage of architecture. Take, for example, his view of the Gothic. What Fr. Reinhold admires about the Gothic is not its simple yet elegant lines, the amazing feeling of lightness it conveys, the breathtaking way it draws the eye upward, or even the beautiful windows such construction made possible. No, what interests him about the Gothic is that it reveals the interior structure of the building externally. So, for example, he says of the Gothic use of the flying buttress: “The skeleton that was hidden in the Romanesque church has, [with the Gothic], grown out of its layers of skin and flesh, and man is turned inside out in his Gothic churches: he shows his interior ... This honesty in construction ... is something we begin again to love.”

And yet, while admiring the Gothic’s “honesty in construction,” still Fr. Reinhold finds it sadly lacking as suitable church architecture. For example, he writes of the magnificent Gothic cathedrals of Canterbury and York: “The beautiful ‘central’ towers of Canterbury and York are a magnificent architectural accent, but have no liturgical, intrinsic function whatsoever.” “The spires of so many cathedrals,” he continues, “though lovely creations, create architectural emphasis around the comparatively insignificant bells—if anything. Even if you consider them as ‘fingers pointing to heaven,’ then the ‘sermon in stone’ or the architectural ‘outcry of the redeemed’ reaches its highest pitch at the gates, or straddles across the joining of the crossbeams in a cruciform church, [but are] unrelated to the internal organs.” Ah yes, the great sin: external structure unrelated to the internal organs.

In fact, according to this principle, as it turns out, almost all the famous churches of Christendom have been failures. Of the legendary Church of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia) in Constantinople, Fr. Reinhold insists that it suffers from having what he calls “misplaced accents.” Notice how the “architectural focus” (line A) and the “liturgical focus” (line B) are out of synch. This must not happen, something that the architects who built Hagia Sophia seem not to have noticed.

And this scandalous problem of “misplaced accents” besets, as it turns out, the majority of Western churches. “In many cases,” says Fr. Reinhold—namely “medieval England, [the] baroque continent, [and] modern America”—in these churches “the accent question was not answered very well.” Notice how the “liturgical focus” (line C) does not line up with the structural foci (lines A and B). This just cannot be allowed. Though lovely creations, these buildings just do not have the right “idea.”

An “Ideogram” of the Ideal Church

What would be the right idea? In answer, Fr. Reinhold offers his reader a diagram—something he calls an “ideogram” of the ideal church. Notice below that the entryway is in the middle between the baptismal font and the main altar. That is Fr. Reinhold’s ideologically preferred place. Following this plan—this ”ideogram”—will finally give us (after centuries of misguided attempts) “suitable” liturgical architecture.

Now Fr. Reinhold is quick to assure his readers that this “ideogram” is not meant to be an actual “architectural design.” And yet, by the same token, even if an “ideogram” is not a full-fledged “architectural design,” it is still specific enough to stipulate that the architect must always put the entryway in the middle of the building, between the altar and the baptismal font. That is not only bizarre; it is what most architects would consider a very distinctive “design feature.”

Be that as it may, Fr. Reinhold insists that his “ideogram” could be built in “Gothic, Renaissance, or Modern Style, if there were good reasons to decide to do so.” How one builds a Gothic or a Romanesque church without a major entryway at the western end—a fundamental characteristic of nearly all churches up until, oh, about the mid-1950s or so—is hard to fathom. And what is more, nowhere in his book does Fr. Reinhold offer us any “good reasons” to build churches in either the Gothic or the Renaissance styles. Indeed, in the conclusion of his book, he positively discourages it. He says of these older styles that they were “children of their own day” and that our architects “must find as good an expression in our language of form, as our fathers did in theirs.”

Church Architecture and the “Spirit of the Age”

But this comment merely shows how distinctively modernist Fr. Reinhold’s mind-set is. For it was Mies van der Rohe who famously described architecture as “the will of the age conceived in spatial terms,”9 and it was Le Corbusier before him who declared: “Our own epoch is determining, day by day, its own style.”10

It would have been completely foreign to a medieval or Renaissance church architect to talk this way. Not only because most of them believed they were expressing their Christian faith by means of their craft, but also because they saw themselves as part of an artistic tradition—one whose standards they had to live up to. Far from looking back on the past with scorn and disdain as something passé (“architecture,” insisted Le Corbusier, “is stifled by custom”11), medieval and Renaissance architects looked upon the tradition of which they were a part with a sense of both pride and humility as something to be emulated and imitated.

And what if the “spirit of the age” is somehow at odds with the “spirit of Christianity”? That thought does not seem to have occurred to Fr. Reinhold. But it certainly occurred to modernists like Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, for whom the “spirit of the age” was clearly meant to effect a “revision of values”12 that would help people to realize that “God is dead” and Christianity obsolete.

Starting from Zero

Indeed, the modernists, rather than seeing themselves as part of a tradition, sought to throw off all those “chains” of the past and create architecture anew—from the ground up—much as Descartes had attempted to re-create philosophy by methodically doubting everything that had come before him. Author Tom Wolfe has written about those who studied in Germany’s Bauhaus, for example, that:

The young architects and artists who came to the Bauhaus to live and study and learn from the Silver Prince [the Bauhaus’s founder, Walter Gropius] talked about “starting from zero.” One heard the phrase all the time: “starting from zero” ... [H]ow pure, how clean, how glorious it was to be ... starting from zero! ... So simple! So beautiful ... It was as if light had been let into one’s dim brain for the first time. My God!—starting from zero! ... If you were young, it was wonderful stuff. Starting from zero referred to nothing less than re-creating the world.13

Just as after Descartes there no longer seemed to be any point in reading the likes of Plato or Aristotle or Thomas Aquinas, so too after Le Corbusier and Gropius, there no longer seemed to be any point in studying Vitruvius or Palladio or any of the work of the classical architects and designers. They were, quite literally, banned from the curriculum in favor of “starting from zero.”

Indeed, modernists would often deny that “functionalism” was part of a “style” at all. For them, “starting from zero” meant getting behind the “mask” of all styles and getting at the essence of what a building is, without any additions of style. This helps to explain the draconian minimalism of most modernist buildings: you strip away all the supposedly superfluous external additions, and what you are left with is just the essence of the building—without “style.” This also helps to explain why, although Fr. Reinhold denies repeatedly throughout his book that the Church should favor any one “style” over any other, he is more than willing to base his entire discussion on one of the central tenets of modernism.

The Church as a Shelter or Skin for Liturgical Action and the Loss of a Recognizable Language of Form

“Starting from zero.” A draconian minimalism. A style which seeks to get behind the “mask” of all style, and a principle of design that says a building should be designed from the inside out. All of these characteristics of modernism go a long way toward explaining why contemporary churches often look so odd: multiple roofs jutting out at perilous angles; impossible-to-find doorways; oblong, narrow, or triangular windows that one never seems to be able to see out of; a bevy of bizarre angles in the nave; little or no symmetry anywhere. Why so strange? Well, one problem is that when you design a building from the inside out, the exterior is often the last thing on your mind. An architecture that designs buildings from the inside out tends to see the exterior of a building primarily as a “covering” or “skin” around a particular interior space or action. For example, the caption of this next photograph, taken from the highly influential little book Environment and Art in Catholic Worship, claims: “The building or cover enclosing the architectural space is a shelter or ‘skin’ for liturgical action.”14 Le Corbusier famously said that a house is a “machine for living in.” Given this view of architecture, I suppose we would have to call a church a “machine for worshipping in.”15 The difficulty with this view, however, is that, in most cases we do not care very much what the outside of a machine looks like. Yes, sometimes we smooth over the rough edges a bit: we put the sewing machine mechanism in a nice, smooth beige-colored container, just as we put the hardware of a computer in a nice beige-colored box. But the automobile engine does not have the shape of sewing machine, and the sewing machine does not have the shape of a laptop computer. In each case, the shape is largely determined by the nature of the mechanism; the outside is a skin that simply covers the mechanism. Such seems to be the mentality that goes into much contemporary church design.

Things were not always thus. Traditionally, architects conceived of the inside and outside of a building as serving two very different purposes and functions. Unlike the private, interior space of a building, the exterior form was generally thought to have a distinctively public, civic function. Indeed, in different places and within various cultures, there generally arose over the years a common and characteristic “language of form” that local building designers could call upon—a language that local citizens could generally recognize and understand.

With modernist “functionalism,” however, we are often left with church buildings that make few, if any, references to the iconic heritage or architectural traditions of the Catholic Church. How exactly, then, are the common, working people of the parish supposed to recognize and understand their own building when it is not speaking their own language of form?

And for those elite few who do understand the “meaning” of the building, what can they say to the pious, hardworking churchgoers whose tithes have gone to pay for the building? That it was the goal of modernists to sweep away all the traditions of the past in order to make way for an architecture that would not only “represent,” but in fact help to create, the new industrial, technological man of the future? It was Le Corbusier who wrote that:

Architecture has for its first duty, in the period of renewal, that of bringing about a revision of values .... We must create the mass-production spirit. The spirit of constructing mass-production houses. The spirit of living in mass-production houses. The spirit of conceiving mass-production houses.

For the rest of the article, go to the link under the photo of a modern church. Contrast it with the equally modern Wo be done.

THE LIVING MERCY SEAT

orth Abbey. The church that heads o

orth Abbey. The church that heads o

THE LIVING MERCY SEAT

orth Abbey. The church that heads o

orth Abbey. The church that heads o