God is a Lover who hungers to be loved in return. Burning with this vision of faith, Catherine Doherty challenged Christians of her day to live a radical Gospel life and to recognize God’s image in every human being.

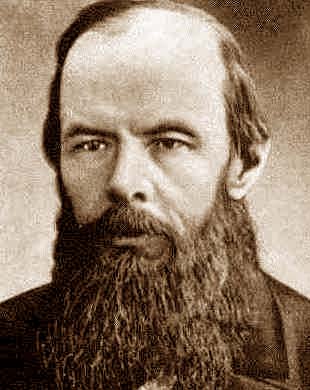

Young Catherine Kolyschkine

She was a pioneer among North American Catholic laity in implementing the Church’s social doctrine in the face of Communism, economic and racial injustice, secularism and apathy. At the same time she insisted that those engaged in social action be rooted in prayer and that they incarnate their faith into every aspect of ordinary life.

Catherine was a bridge between the Christian East and West. Baptized Orthodox and later becoming Roman Catholic, her spiritual heritage drew upon both of these traditions.

Catherine Kolyschkine was born in Nizhny-Novgorod, Russia, on August 15, 1896 to wealthy and deeply Christian parents. Raised in a devout aristocratic family, she grew up knowing that Christ lives in the poor, and that ordinary life is meant to be holy. Her father’s work enabled the family to travel extensively in Catherine’s youth.

At the age of 15, she married her cousin, Boris de Hueck. Soon, the turmoil of World War I sent them both to the Russian front: Boris as an engineer, Catherine as a nurse.

The Russian Revolution destroyed the world they knew. Many of their family members were killed, and they themselves narrowly escaped death at the hands of the Bolsheviks.

The Revolution marked Catherine for life. She saw it as the tragic consequence of a Christian society’s failure to incarnate its faith. All her life she cried out against the hypocrisy of those who professed to follow Christ, while failing to serve him in others.

Catherine and Boris became refugees, fleeing first to England, and then in 1921, to Canada, where their son George was born. In the following years she experienced grinding poverty as she laboured to support her ailing husband and child. After years of painful struggle, her marriage to Boris fell apart; later her marriage was annulled by the Church.

Catherine, Baroness

Catherine’s talent as a speaker was discovered by an agent from a lecture bureau. She began travelling across North America, and became a successful lecturer. Once again she became wealthy—but she was not at peace. The words of Christ pursued her relentlessly: “Sell all you possess, and come, follow Me.” On October 15, 1930 Catherine renewed a promise she had made to God during her ordeal in the revolution, and gave her life to Him. She marked this as the day of the beginning of her Apostolate. With the blessing of Archbishop Neil McNeil of Toronto, Catherine sold all her possessions and provided for her son, George.

In the early 1930’s she went to live a hidden life in the slums of Toronto, desiring to console her beloved Lord as a lay apostle by being one with his poor.

The lay apostolate was still in its infancy in the 1930’s. Dorothy Day, another pioneer in this field, was among the few who understood and supported what Catherine was trying to do. Catherine searched for direction, prompted by an inner conviction that she must preach the Gospel with her life. As she implemented this radical Gospel way of life, young men and women came to join her. They called themselves Friendship House, and lived the spirituality of St. Francis of Assisi.

In the midst of the Great Depression of the 1930’s, the members of Friendship House responded to the needs of the time. They begged for food and clothing to share with those in need and offered hospitality of the heart to all. They also tried to fight the rising tide of Communism, through lectures, classes, and the distribution of a newspaper called “The Social Forum”, based on the great social encyclicals of the Church.

Misunderstanding and calumny plagued Catherine all of her life. False but persistent rumours about her and the working of Friendship House forced its closing in 1936. Catherine left Toronto, feeling her work had failed. Through the seeming failure and great disappointments, she heard the voice of Christ beckoning her to share His suffering.

Soon after she left Toronto, Father John LaFarge, S.J., a well-known Civil Rights Movement leader in the U.S., invited Catherine to open a Friendship House in Harlem. In February, 1938, she accepted his request, and soon the Harlem Friendship House was bursting with activity. Catherine saw the beauty of the Black people and was horrified by the injustices being done to them. She travelled the country decrying racial discrimination against Blacks.

In the midst of widespread rejection and persecution, she found support from Cardinal Patrick Hayes and Cardinal Francis Spellman of New York. In Harlem, a small community formed around her, but again, her work ended in failure. Divisions developed among the staff of Friendship House and in January, 1947, they out-voted Catherine on points she considered essential to the apostolate. Seeing this as a rejection of her vision of Friendship House, she stepped down as Director General.

Eddie Doherty and Catherine.

On May 17, 1947, Catherine came to Combermere, Ontario, Canada, with her second husband, American journalist Eddie Doherty, whom she had married in 1943. Catherine was shattered by the rejection of Friendship House and thought she had come to Ontario to retire. Instead, the most fruitful and lasting phase of her apostolic life was about to begin. As she was recovering from the trauma, Catherine began to serve those in need in the Combermere area, first as a nurse and then through neighbourly services. She and Eddie also established a newspaper, Restoration, and eventually began a training centre for the Catholic lay apostolate.

At a summer school of Catholic Action that Catherine organized in 1950, Fr. John Callahan came to teach. He was to become Catherine and Eddie’s spiritual director and the first priest member of Madonna House. Under his guidance, in February 1951, they made an act of consecration to Jesus through Mary, according to St. Louis de Montfort. Mary, Mother of the Church, became guide to their lives and to their apostolate.

Catherine’s lifelong passion to console Christ in others propelled her forward. Again young men and women asked to join her. Graces abounded. In October 1951, Catherine attended the first Lay Congress in Rome. The Papal Secretary, Msgr. Montini (later to become Pope Paul VI) encouraged Catherine and her followers to consider making a permanent commitment.

Pope John Paul II and Catherine Doherty

On April 7, 1954, those living in Combermere voted to embrace a permanent vocation with promises of poverty, chastity and obedience, and the community of Madonna House was established. The following year, Catherine and Eddie took a promise of chastity and lived celibate lives thereafter. From these offerings, an explosion of life took place and Madonna House grew. On June 8, 1960, Bishop William Smith of Pembroke offered the Church’s approval to the fledgling community at the blessing of the statue of Our Lady of Combermere.

Catherine had a faith vision for the restoration of the Church and our modern culture at a time when the de-Christianization of the Western world was already well advanced. She brought the spiritual intuitions of the Christian East to North America. Lay men and women as well as priests came to Madonna House to live the life of a Christian family: the life of Nazareth. They begged for what they needed and gave the rest away. At the invitation of bishops, they opened houses in rural areas and cities in North and South America, Europe, Russia, Africa, and the West Indies.

Catherine’s vision was immense, encompassing farming, carpentry, cooking and laundry, theology and philosophy, science, the fine arts, and drama. “Nothing is foreign to the Apostolate, except sin… The primary work of the Apostolate is to love one another… If we implement this law of love, if we clothe it with our flesh, we shall become a light to the world,” she said, “for the essence of our Apostolate is love—love for God poured out abundantly for others.”

In response to the deepening dilemmas of the Western world, Catherine offered the spirituality of her Russian past. She introduced the concept of poustinia, which was totally unknown in the West in the 1960’s, but has since become recognized in much of the world. Poustinia is the Russian word for “desert,” which in its spiritual context is a place where a person meets God through solitude, prayer and fasting. Catherine’s vision and practical way of living the Gospel in ordinary life became recognized as a remedy to the depersonalizing effects of modern technology.

In response to the rampant individualism of our century, she called Madonna House to sobornost, a Russian word meaning deep unity of heart and mind in the Holy Trinity—a unity beyond purely human capacity.

Catherine de Hueck Doherty died on December 14, 1985, after a long illness. She left behind a spiritual family of more than 200 members, and foundations around the world. She left to the Church, which she loved passionately, a spiritual heritage that is a beacon for this new century. The following is taken from a Letter to Madonna House Family:

“We need to be poor! Let us live an ordinary life, but, beloved, let us live it with a passionate love for God. Become a mystery. Stretch one hand out to God, the other to your neighbour. Be cruciform. … Christ’s cross will be our revolution and it will be a revolution of love!”

Catherine and the Russian Religious Renaissance

Catherine: Cause Newsletter #19 — Fall 2011

From the Postulator’s desk of Father Robert Wild

Catherine Doherty by a Russian shrine

The Communist Revolution in Russia was of such enormous consequence that other important events happening in Russia in the latter part of the 19th and the early part of the 20th century have gone relatively unnoticed. In this very brief account of Catherine’s relationship to what has been called the Russian Religious Renaissance (RRR) I will spare you references and many quotations—one exception to this will be some quotes from Nicholas Zernov’s The Russian Religious Renaissance—and simply say that my presentation is based on the work of scholars and that the facts related here are fairly widely known to those studying in this field.

After what was called the Golden Age in Russian art and philosophy exemplified by such well-known writers as Pushkin, Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, and Khomyakov, there followed what has been called the Silver Age, a spiritual and cultural movement of even greater intensity. There was an explosion of novels, poetry, music, philosophy, and “religious philosophy,” this latter being a mix of philosophy, theology, and spirituality. When the Communists took over, a number of the most brilliant members of this Silver Age were exiled by Lenin. Their expulsion has been called “an unsolved mystery. It is possible that in this unusual decision flickered the last spark [in Lenin] of suppressed humanism.” Some scholars speculate they were not executed or sent to camps because in their early periods they dabbled in Marxism, and so contributed in some way to the final advent of Communism. But these intelligentsia, in the early part of their thinking careers, quickly saw the many enormous economic, philosophical, and religious flaws in Marxism. They helped the Marxist movement a little, but not much, and not for long.

Some of the most brilliant of the philosophers and theologians—Sergius Bulgakov, Nicholas Berdyaev, S.L. Frank, and Vladimir Lossky—made their way to Paris where they were either directly or indirectly involved in establishing the Theological Institute of St. Sergius. Names more familiar to North Americans who were not born in Russia are Alexander Schmemann (Estonia) and John Meyendorff (Paris). They were educated at St. Sergius and brought some of its Russian treasures to North America via St. Vladimir Seminary in New York City. Scholars are now saying that the full flowering of the Silver Age, begun in Russia but displaced by the revolution, really occurred outside of Russia, as a consequence of an open contact with the western intellectual traditions, and because they now had the complete freedom to write and express their creative ideas. For the purposes of this article it is significant that historians called this a religious and not a philosophical, cultural, or artistic renaissance. To repeat: this was a flowering of the Silver Age outside of Russia.

RRR refers mostly to intellectuals who taught and wrote in the areas of theology, philosophy, history, sociology, law, and art. Understandably, its history and scope is limited to those of the Russian Orthodox Church. In bibliographies some works of spirituality are included, but the main thrust of literally hundreds of books and articles (mostly in Russian) are centered on the concerns of the intelligentsia in Russia before their expulsion.

The main point of this brief article is that those exiles who developed Russian spirituality but who had converted to the Catholic Church should be equally included in the RRR. The contributions of Catherine and others who became Catholics may not be completely Russian because of their new allegiance. However, there were Russian Catholics before the revolution, and Russian Catholicism should be considered as part of Russia’s contribution to the modern Christian world. My emphasis will be on recognized participants in the RRR in the area of spirituality, in which sphere Catherine should be included. I will simply mention some of the more well known of this Renaissance of Russian spirituality outside of Russia; they are listed in Zernov as part of the RRR.

The real inspiration for this article—for making a plea that Catherine be included in the RRR which flowered outside of Russia—came as a result of my visit to the Oriental Institute in Rome. It was one of the remarks of the vice-rector, Fr. Constantin Simon, S.J., that convinced me that Catherine, though a member of the Catholic Church, should be included among those who have brought the treasures of Russia to the West.

Fr. Constantin had just finished writing the history of the Russian Catholic Church and was very familiar with Catherine. He said that Catherine’s writings had done more to bring Russian spirituality to the West than all the writings of the intellectuals. (This was his opinion, of course, and many will think it is exaggerated.) But this convinced me that Catherine and those who brought Russian spirituality to the West, even though they were not Orthodox, should also be considered as part of the RRR.

Zernov includes examples of Russian spirituality in the RRR, and I wish Catherine to be included in this group. The ones mentioned here were also part of Catherine’s spiritual development.

Spirituality in the Silver Age

Staretz Silouan

Staretz Silouan was from Russia, although his spirituality flourished in the Russian monastery of St. Panteleimon on Mt. Athos in Greece. Still, this is the West, and his spirituality grew in a garden free from the influences of the Soviet Union. Through the publication of his writings (The Undistorted Image) we have benefited by an authentic expression of Russian spirituality. It was one of Catherine’s favorite books, and she often read from it publicly and commented on it.

We owe the publication of Silouan’s works to another religious genius, Archimandrite Sofrony. Also from Russia (b.1896) he travelled to Paris and thence to Athos and became a disciple of Silouan. Later he developed his own unique form of Russian spirituality by establishing the monastery of St. John the Baptist near Maldon, Essex, England. I had the privilege of meeting him there; and after his death some other members of our Madonna House community also visited. One of the new aspects of his spirituality—and therefore of the Russian spiritual renaissance—is that St. John’s is a community of both men and women, a great departure from Orthodox monasticism; it may still be unique in the Orthodox world. Needless to say, such a monastic existence is a very appealing development of Russian spirituality to members of Madonna House who live in a community of women and men. This form of community life-styles is, I believe, one of the legitimate developments of Russian spirituality in the RRR, and forms a kinship between Catherine and Sofrony.

Another fairly well known propagator of Russian spirituality was Archbishop Anthony Bloom of England. His writings (Living Prayer, Learning to Pray) were also among Catherine’s favorites.

Some westerners were greatly influenced by these displaced Russians in Paris. The Benedictine Fr. Lev Gillet (publishing under the nom de plume of a Monk of the Eastern Church) made the modern classic, The Way of the Pilgrim, popular in the West.

Elisabeth Behr Sigel, probably less well known, converted from Lutheranism to Russian Orthodoxy, and contributed to an understanding of Russian'

Orthodoxy in the West.

Maria Skobtsova

But perhaps the person closest to Catherine in both life-style and writings is Mother Maria Skobtsova. Because of her background in poetry, literature, politics (she was the first woman mayor of a small Russian town), and theology, she is described by Zernov as “the most original personality among the Christian leaders of the intelligentsia.” She was a married woman, a mother, who became an Orthodox nun “in the world” in Paris. She had an extraordinary love for the poor, as did Catherine. She died in a concentration camp for harboring Jews. She has recently been canonized by the Russian Church. Some people have already started working on a comparison of her spirituality with Catherine’s, because they are very, very similar. If you have never read any of her writings, I highly recommend them.

Catherine and Vladimir Soloviev

Many consider Vladimir Soloviev the greatest Russian philosopher/theologian of all time. Although he died in Russia in 1900, and was not part of the RRR outside of Russia, he is considered the creative genius and inspiration of the Silver Age. Thinkers such as Bulgakov, Berdyaev, Lossky, and others were inspired by his genius and built upon, and continued, his legacy. We can find, therefore, in his writings, the great themes that were developed in the RRR. The writings and teachings of Soloviev is one of the great documented links between Catherine and the RRR.

Vladimir Soloviev

Her father used to read Soloviev to them as children; and she said publicly once that she was a “product of Soloviev.” She certainly read some of his writings; she had his whole collection of letters in her possession—of course, in Russian. His ideas became the themes of the RRR, and Catherine developed, lived, and wrote about these themes in her own unique way, adding to the riches of the RRR in the West. And so I will simply state some of these topics. (They were the interests also of the theologian who is considered Soloviev’s greatest heir, Sergius Bulgakov.)

Since many of my present readers are familiar with Catherine’s writings, I will now just briefly allude to some of the main themes of her teachings, and indicate how they were also the concerns of the Silver Age, and thus of the RRR.

“Godmanhood” and Ecumenism

One of the first public and major presentations of Soloviev’s thought, attended by Dostoyevsky and Tolstoy—and probably also Catherine’s father—was entitled Lectures on Godmanhood, his word for the unity of the human race in Christ. Christ was not a theory but an absolute fact of history. Soloviev’s whole teaching was built on the fact of our world history—the Incarnation of God. Catherine longed for this unity. Her body of teaching is a profound guide of how each individual can contribute to the growth of this Godmanhood.

It has been said that the question that preoccupied the Russians during the period of the Silver Age was, “How is society to be organized?” Almost every piece of Russian art, poetry, or even music of the Silver Age made some reference to “the people” and their social problems. The Tsarists, the secular humanists, the Marxists, all had their theories. The little village of Madonna House in Combermere is Catherine’s answer to this central problem of the Silver Age, or of any age. The teaching that forms our community of love flowed from many sources, but Catherine’s Russian roots are the primary fountainhead.

It is widely known that ecumenism is not Orthodoxy’s strong suit. As an ecumenist in the late 19th century, Soloviev was far in advance of his Orthodox confreres. He believed in the development of doctrine around the same time that Blessed Cardinal Newman was writing his own treatise by that title. Neither is Orthodoxy particularly known for its approval of the development of doctrine. But Soloviev pointed out that the history of the Church includes the bible, tradition and the Holy Spirit, who is always active and working to make scripture and tradition relevant and understandable, “like the householder who brings out of his storehouse thing new and old” (Matt.13:52). The Holy Spirit is the origin of newness, and thus there is always development in doctrine and in the Church.

Applying this notion of development to Catherine, she had a great devotion to the Holy Spirit. Thus, she did not simply pass on Russian spirituality as it was handed down from past ages. She was extremely creative in uniting doctrine, her experience, and listening to the movements of the Holy Spirit. Her teaching is, therefore, very unique, distinctive, and a good example of the development of spirituality. Just as it was Newman’s study of the development of doctrine that brought him into the Catholic Church, so it brought Soloviev to study the history of the Church.

He presented his findings of the history of the Church in his book Russia and the Universal Church. His conclusion was so revolutionary—I would say prophetic!—that it had to be published outside of Russia. What was his conclusion? That the whole Church must have a head, and that historically this was the bishop of Rome. He called the Pope the “wonder-working icon of Christian unity”, and this in the last quarter of the 19th century in Orthodox Russia! Needless to say, this was not popular with the Orthodoxy of his day. It is debatable whether or not he became a Catholic. Probably he simply saw his recognition of the papacy as a necessary complement to his Orthodox faith. But no doubt his writings influenced Catherine to enter the Catholic Church in a formal way without, as far as I can discover, any really traumatic break with her religious past.

Love and Judaism

Vladimir Soloviev (portrait, 1885)

Soloviev, in delivering his Lectures on Godmanhood, probably astonished everyone at the beginning by saying that he agreed with those who found modern Christianity irrelevant! He said Christianity was practiced in his day in some kind of separate compartment of life; it did not influence the whole of life as it should. This was one of Catherine’s constant themes also: that nothing in life is outside the sphere of the Gospel. From my study of her life and writings I believe she got this vision from Soloviev.

Soloviev’s book, The Meaning of Love, was considered by the great psychiatrist Karl Stern to be the best book on love ever written. As is well known, love was everything for Catherine, and this theme permeates all of Soloviev’s writings. Besides often speaking of God’s love for us and ours for him, and of our loving others, Catherine often emphasized that we must love ourselves as well. Soloviev wrote: “Failure to recognize one’s own absolute significance is equivalent to a denial of human worth; this is a basic error and the origin of all unbelief. If one is so faint-hearted that he is powerless even to believe in himself, how can he believe in anything else?”

Soloviev lost his teaching position in Moscow for some of his revolutionary and prophetic ideas. Among them was that anti-Semitism is contrary to the Gospel. There was a great deal of anti-Semitism in Russia, even more than in Germany. “Pogrom” is a Russian word. Soloviev simply pointed out that Jesus was Jewish, and that most of the first Christians were Jewish. And more than 100 years before Pope Benedict would say clearly, once and for all, that only a handful of the Jewish elders can be held responsible for the death of Jesus, Soloviev was teaching this as well: there is no theological or biblical support for the doctrine that all the Jews, as a people, are responsible for the death of Christ. If anything, we are all responsible.

Catherine often told us of how her father used to invite Jewish people to their home. When she asked him about this he said he was following the teaching of a very great man. When Catherine asked him who that man was, he said Soloviev. Catherine always had a great love for the Jews, and often, along with Pope John XXIII, reminded us of our Jewish spiritual roots. (It is more accurate to say we are spiritually Jewish (a religion), than Semites (a race).

As a real prophet, Soloviev was calling for the union of Orthodoxy and Catholicism before anyone else seriously entertained the hope. His vision of Godmanhood required the unity of the churches. (He pointed out that the Orthodox churches were not united either.) He even had an audience with Pope Leo XIII who, of course, had the same desire, but said it would require a miracle to be achieved at that time.

The founders of the St. Sergius Institute continued to work for this unity. Sergius Bulgakov, especially, was involved in the early deliberations of the World Council of Churches, and many of the members of the RRR were deeply committed to Church unity. Again, this was not a priority of Orthodoxy in Russia but a result of Soloviev’s vision, and of the contact of the Russian émigrés with the West; it was a prominent feature of the RRR.

Here again Catherine shows her solidarity with the RRR and can rightly be considered a part of this movement. All her life, in a variety of ways, she worked for, prayed for, hoped for the unity of Christendom, and most of all for the reunion of Orthodoxy and Catholicism. Madonna House tries to live and breathe with both lungs of the Church, as famously articulated by Bl. John Paul II. In this also she is part of the best movements of the RRR, not academically, but, in her own way, by a living personal union with both of these great traditions.

Of course, I have not read very much of recent literature regarding the RRR. But, except for Fr. Constantin mentioned above, I have never read of Catherine being included in this flowering of the Silver Age outside of Russia. I think the main cause may simply be that she is simply unknown in most academic circles. And her having become a Catholic may dampen interest.

The Silver Age as Renaissance and Flowering

Scholars (Catherine Evtuhov) ask: “Why was the religious theme so pervasive and insistent at a time that social historians, quite rightly, tell us was an age of industrialization, urbanization, modernization, and revolution?” Several answers are given. I choose the one most applicable to Catherine and which is an authentic part of the renaissance as distinguished from a flowering: “Ernst Troeltsch considered the Eastern Church to have remained ‘genuinely medieval’ into the twentieth century, for it retained the Middle Ages’ ‘unity of civilization which combined the sacred and the secular, the natural and the supernatural, the State and the Church.’” The intelligentsia (continues Evtuhov) “understood that reform in the church could hold the key to reform in society as a whole.”

Russians go to the root of things. Their own revolt against the isms of the 20th century “took them all the way, and ended up with modernist philosophy that was also deeply religious.” They were still grafted on to “a tree whose roots went deep into the soil still fed by the living waters of Eastern Orthodoxy.” (Zernov) It led them back to the medieval vision of Church and society. In their writings they sought to purify both government and church of whatever was contrary to true freedom and the correct idea of person. But they retained the vision of the Church’s overarching place in morals, culture, and thought.

When Catherine came to the West the secularization of society was very far advanced. She must have experienced a real culture shock at the lack of the presence of the Church and religion in society. Religion was very compartmentalized, as Soloviev said. Unlike most of the intelligentsia in their early periods, she probably never lost the medieval vision that they had to resurrect—give re-birth to—in their minds and thinking. And she found this vision also in the Catholic Church, even though its permeation of society also had much to be desired. But this medieval vision was part of Catherine’s vision for the fulfillment of Godmanhood in society. And Madonna House—though on a small scale—is the incarnation of this vision: it deeply links her spiritually and ideologically to the RRR.

My final point is that we may need an additional term to describe these émigrés of Russia who made contributions to the West in the areas of theology, philosophy, spirituality, art, and culture.

In this article I have been using a word that I think is also appropriate to this movement in a complementary way. Besides the word renaissance, which implies the rebirth of something from the past (like the rebirth of the classics in the West), what strikes me as also appropriate is the word flowering. Russia is a relatively new Christian people: the gospel was brought there almost 1,000 years later than it came to Greece, Rome, and Western Europe. And just as the 13th century in the West is often called the greatest of the centuries—the flowering of the fruits of a thousand years of Christianity with cathedrals, music, the visual arts, theology and philosophy—so Russia entered its greatest Christian century in the 20th. But it was not only through a renaissance but also through a long-awaited flowering of 1,000 years of Christianity.

Soloviev, Bulgakov, Bloom, Lossky, Evdokimov, Saint Maria Skobtsova, Schmemann, and Meyendorff are not only part of a Russian renaissance but, as with Catherine, they are a flowering of a Russian expression of the Gospel, and probably the high point of that flowering. As it took Christianity in the West 1,000 years to achieve the 13th century, likewise, after 1,000 years, the Russian spirit finally exploded in a flowering of creativity. We cannot know what other immense treasures would have been brought forth if some kind of Christian sanity had prevailed in 1917, and if these geniuses had been allowed to bloom on their native soil. However, such blossoming could not be stopped. The Russians who left Russia carried their immense treasure with them, the seeds of their whole history. And it was providentially forced to grow outside of Russia only because of the revolution.

It should also be emphasized that this flowering was as much a result of the Russian spirit itself as of its contact with the West and Western Christianity. Even in the Silver Age still within Russia, scholars attribute much of its fruitfulness to its contact with Western art and philosophy in the 19th century. This flowering is part of that incarnation of the Godmanhood Soloviev so well described and longed for. He taught that it could not be achieved without the union of the churches and the cross-fertilization of the truths of other cultures. And if the final union has not yet happened, there has been at least a significant union of minds and hearts—as in Catherine—of the best of the Russians with the best of the West. Madonna House is one of the authentic incarnations of the vision that inspired the members of the RRR. I think Soloviev would be pleased with what has happened in the minds and hearts of those involved in the RRR; and he would be pleased as well with Catherine and Madonna House.