ADAM, EVE, AND SETH: PNEUMATOLOGICAL REFLECTIONS ON AN UNUSUAL IMAGE IN GREGORY OF NAZIANZUS

Alexander Golitzin

I have been asked to contribute to this volume primarily, I suspect, in order to serve as the voice of the Christian East. While it is perhaps a little odd for a California boy, and coming thus from the uttermost West, to present himself as an "Oriental," I nonetheless welcome this opportunity to speak on behalf of an entire Christian universe of theological discourse which, up until recent centuries at least, took shape independently of the Western (Roman Catholic and Protestant) traditions, and, in particular, with no input whatsoever from the great Father of Western theology, Augustine of Hippo.

It is, of course, St. Augustine's elaboration and defense of the double procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father and the Son which, long after the saint's death (his writings were not translated into Greek until the end of the thirteenth century), provoked heated controversy between medieval Greek and Latin theologians. No single issue between Christian East and West, including the debate over the nature of papal primacy, has led to such an outpouring of polemic as the Western filioque. Indeed, it continues to the present day.

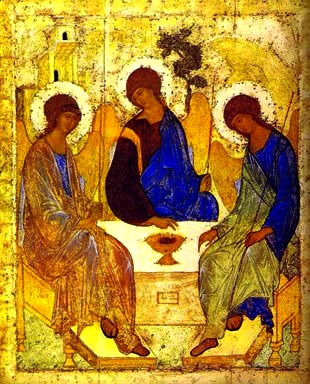

I have no particular wish to dive into this sea of ink, and have so far in my life happily avoided even wading on its shores. Few things so depress the spirit (and occlude the Spirit!) as this seemingly endless controversial literature which, beginning with the Carolingian divines of the late eighth century, now boasts a history of over 1200 years--with no end to it in sight. What I do want to do, however, is offer a very modest suggestion as to why, aside from the more abstruse realms of divine causation, such as the quarrel over one or two sources of origin in the Trinity, or over the more rarified heights of Augustine's analogy of the intellect (mens) for the mutual relations of the Three, Eastern Christians reacted so viscerally, almost instinctively, against the Spirit as proceeding from the Father and Son.

To be sure, there were and are lots of other factors in play: the ancient linkage between the filioque and the legitimacy or illegitimacy of the Carolingian and Byzantine empires, or of papal primacy once the popes had committed themselves to the credal addition, or simply the very human reality of an underdog East asserting itself against the ever more massive material, intellectual, and institutional might of the West.

None of these interests me, at least for the purposes of this essay. What does, though, is the very long, indeed unbroken tradition of Eastern Christian spirituality, and especially the great role played in it by the thought and practice of early Christian Syria, whose Jewish roots are well known and are lately coming under increasing scholarly investigation.

One instance of this influence, only now beginning to be perceived, is that of the Cappadocian Fathers--Basil the Great, Gregory Nazianzus, and Gregory of Nyssa--whose own influence on Eastern pneumatology and triadology is universally admitted and standard fare in the manuals.

This is a vast subject, so for the purposes of one necessarily brief essay allow me to focus on a single passage from the writings of the middle Cappadocian, Gregory Nazianzus, called "the Theologian" in the East out of gratitude for his enormously influential and successful Five Theological Orations, given in defense of Trinitarian doctrine in Constantinople just prior to the Ecumenical Council of 381. The passage in question comes about a third of the way through Gregory's fifth oration, "On the Spirit." He is struggling to explain the difference between the procession (ekporeusis) of the Spirit and the generation (gennesis) of the Son, in order to avoid the twin absurdities of the Son and Spirit as brothers, on the one hand, or the Father as "grandfather" on the other. This is, of course, the point where Augustine's analogies in De trinitate came into play: the Spirit as "love" and "gift" linking "Lover" (Father) and "Beloved" (the Son), or the analogy of the intellect, with will (Spirit) as flowing from memory (Father) and intelligence (Son).

Gregory does something quite different and even a little shocking:

What was Adam? A creature of God. What, then, was Eve? A fragment of the creature. And what was Seth? The begotten of both. Does it, then, seem to you that creature and fragment and begotten are the same thing? Of course not. But were not these persons consubstantial? Of course they were.

He interjects the caution that his scriptural image is not intended to "attribute creation or fraction or any property of the body to the God-head," but then goes on to explain

the meaning of all this. For is not the one an offspring, and the other a something else of the One? Did not Eve and Seth come from the one Adam? And were they both begotten by him? No ... yet the two were one and the same thing ... both were human beings.

"Will you then," he addresses his opponents, "give up your contention against the Spirit, that He must be altogether begotten, or else cannot be consubstantial, or God?"[1] He has demonstrated, through the illustration of Eve's beginning, a mode of origin that is not begetting, but a "something else of the One."

Gregory does not pursue this analogy beyond what I have quoted here, and as far as I know it appears in Greek patristic literature only this once. Perhaps this is why it has not been taken up and examined in detail by the scholarly literature, though I claim no encyclopedic knowledge of the latter. This neglect may be understandable, in that the mental picture which rises unbidden and unwelcome, yet inescapably, from Gregory's image is weird, to say the least, if not positively blasphemous--thus, doubtless, his caution against attributing "any property of the body to the Godhead." On the one hand, he has certainly come up with a very concrete mode of origin that is not begetting, but that very concreteness, on the other hand, cannot avoid giving rise to a certain theological queasiness. I am reminded of nothing so much as my first-grade primer featuring the adventures of Daddy and Mommy, Dick and Jane, and their dog Spot. True, Jane and Spot are missing from Gregory's picture, but the Trinity as nuclear family is otherwise quite complete, and even, we might say, in its limitation to only three ecologically a la mode as well: Adam (the Father), Eve (the Spirit), and their child, Seth (the Son).

The now uneasy reader might also recall at this point Mormon teaching about Mr. and Mrs. God, though I seem to recall that the Mormons do not particularly identify the Spirit with Herself, Whom in any case they generally keep pretty much under wraps.

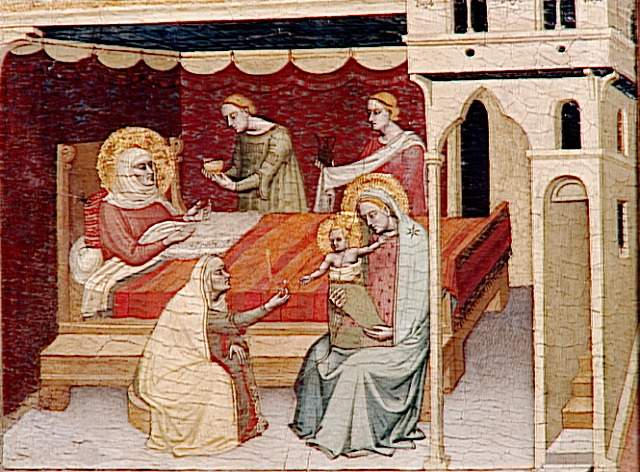

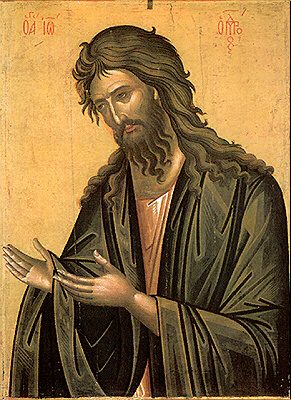

St. Gregory is certainly not a Mormon, but he is, I submit, drawing here on ancient traditions which were especially lively in early Syriac-speaking Christianity and which continue to run--not so openly, but still very deeply--in the wider Christian world east of the Adriatic. These derive first of all from the simple, grammatical fact that spirit or breath, ruach, is a feminine noun in both Hebrew and Aramaic/Syriac. To this we may add, second, the Synoptic accounts of Christ's baptism at the Jordan and, third, St. Luke's narrative of the Lord's nativity, in particular the words of Gabriel addressed to the Virgin: "The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the Power of the Most High will overshadow [episkiasei] you; therefore the child to be born of you will be called holy, the Son of God" (Luke 1:35), words which are reflected indeed in the Niceno-Constantinopolitanum: "made flesh of the Holy Spirit and the Virgin Mary." As Susan Harvey has recently pointed out with great thoroughness and theological restraint, the grammatical use of the feminine for the Spirit remains normative in Syriac Christian literature through the fourth century.

[2] The Gospel story of Christ's baptism and the resting of the Spirit upon Him appears to have been not only central to the earliest Syrian baptismal ordinals, but as well their primary source for the theology of baptism and the Christian life--to the exclusion, for example, of the Pauline notion of sharing in Christ's death (Rom. 6), which only later, sometime in the late fourth century, finds its way into the rite. Likewise, the feast of Epiphany in the East celebrates the baptism at the Jordan and continues to enjoy a more notable prestige (at least judging from the texts and hymns assigned to it) than Christmas, which only later, in imitation of the West, came to be commemorated on its own separate date (save in the case of the Armenians, who have never adopted the Western practice).

[3] To this list I would add the well-known matter of the Eastern epiklesis, itself a source of considerable medieval debate between Greek and Latin theologians over the moment of the eucharistic consecration, i.e., whether the latter takes place at the recitation of the dominical words, hoc est corpus meum, or at the conclusion of the prayer for the Spirit to "make this bread the body of Your Christ." The great Syriac poet and preacher, Jacob of Serug (+521), catches nearly all of these echoes in a few lines from his verse homily "On the Chariot that Ezekiel the Prophet Saw," commenting here on Ezek. 10:6-7 as an image of the eucharist:

It is not the priest [typified by the prophet's "angel in

white linen"] who is sent to sacrifice the Only[-Begotten],

And lift Him up, Who is the sacrifice for sins, before His

Father.

Rather, the Holy Spirit comes down from the Father,

And descending overshadows [sr] and dwells [skn] within the

bread and makes it the body.

And it is He Who makes it kindled pearls of flame,

And Who will clothe those who are betrothed to Him with

riches.[4]

True, Jacob is no longer saying "she" for the Spirit, but nearly everything else--the baptismal narratives and theology, together with Luke 1:35's echo of Exodus 40:34, and the note of transfiguration in the clothing "with riches"--is fully present and accounted for in this image of the eucharistic consecration.

St. Gregory's use of Adam, Eve, and Seth--the "nuclear family"-has even more specific echoes in earlier and even contemporary fourth-century literature. The Holy Spirit as "Mother" of Christ appears, for example, in the fragments we possess of the Semitic Gospel to the Hebrews,[5] while the "family" shows up complete in the strange and beautiful "Hymn of the Pearl," thought by an earlier generation of scholars to be wholly Gnostic in character, but recognized more recently as an essentially Semitic-Christian composition.

[6] Placed in the mouth of the Apostle in the mid-third-century Acts of Thomas, a work advocating typically fierce--even heretically encratite (though not Gnostic)--Syrian asceticism, the "Hymn" describes the descent and return of the soul. It concludes with the speaker's being clothed with the "robe of light," an ancient Jewish and Christian motif (and recall Jacob just above),[7] which in context is clearly intended to signify both transfiguration and the mystical ascent to the heavenly throne, two more themes with roots in ancient Jewish literature and Eastern Christian spiritual writings.[8] What particularly catches my eye for our purposes here are a few lines from midway through the poem. The speaker tells of a letter sent to him in "Egypt" (the fallen world) from his "parents" in heaven, and then quotes it:

From thy Father, the king of kings,

And thy Mother, the mistress of the East,

And from thy brother, our other Son,

To thee, our son in Egypt, greeting!

Awake, and rise up from sleep![9]

Here we have the by now familiar Trinitarian formula: the Father, the Mother (the Holy Spirit, as appears elsewhere in the Acts of Thomas), and the Son, Christ our "brother." Neither is this formula a one-time-only business, nor is it confined to a text of an admittedly still debated nature and provenance.

We find exactly the same formulation in the enormously influential early monastic homilies and correspondence which have come down to us under the name of St. Macarius the Great of Egypt, but which were in fact the product of an unknown Syro-Mesopotamian ascetic. In the well-known collection of The Fifty Spiritual Homilies, "Macarius" links the plague of darkness in Egypt with the fall of Adam:

The veil of darkness came upon his [Adam's] soul. And from

his time until the last Adam, our Lord, man did not see the

true heavenly Father and the good and kind Mother, the grace

of the Spirit, and the sweet and desired Brother, the Lord,

and the friends and relatives, the holy angels, with whom he

[Adam] had been playing and rejoicing.[10]

"Macarius" was not writing in Syriac, but in Greek. He also appears to have directly influenced the third great Cappadocian, Gregory of Nyssa, in at least one of the latter's ascetical and mystical works. Together with one of Gregory Nazianzus's disciples, Evagrius of Pontus (+399), "Macarius" indeed ranks as one of the two most important fourth-century monastic sources for later Eastern Christian spirituality and mysticism. He was not, in short and in spite of the controversy (both ancient and modern) attaching to his works, a marginal character, but was right in the midst of those figures and currents that would determine the later shape of Christian orthodoxy.

Gilles Quispel and Columba Stewart have clearly demonstrated "Macarius's" other debts as well, notably to the originally Jewish-based traditions of Christian Syro-Mesopotamia, and in fact to the Syriac language itself.[11] The extent to which these same influences may have been at work in the great Cappadocians is, as I noted briefly above, only just beginning to come to light.

If my much abbreviated sampling from the early and fourth-century Syrian East has successfully demonstrated that Gregory Nazianzus was not pulling his Adam-Eve-Seth analogy out of thin air, but was rather reflecting ancient formulations of the Christian Trinity current in the surrounding region, we are still left with a couple of obvious questions. First, what if anything does this archaic and to the modern Christian ear unquestionably bizarre image have to do with contemporary theological reflection on the Trinity? Second, and more specifically, what does it have to do with the issue I raised at the beginning of this little essay, the almost equally ancient but still very lively question of the filioque and the matter of the ecumenical dialogue between Christian East and West? I think it says quite a lot, not all of which I have time to expand on here. Suffice it to say that St. Gregory's recourse to the first human family as an illustration of the Trinity is, first of all, explicitly related to the question of the Spirit's origin, and to the difference between the latter and the generation of the Son--Eve from the side of Adam as opposed to the begetting of Seth. This is, indeed, quite as far as Gregory wants to take this or any other analogy.[12] The Spirit's procession is different from the Son's begetting, both are from the Father, and both processes are finally hidden and ineffable:

You tell me what is the unbegottenness of the Father, and I

will explain the physiology of the generation of the Son and

the procession of the Spirit, and we shall both of us be

stricken with madness for prying into the mystery of God.

And who are we to do these things, we who cannot even see

what lies at our feet ... much less enter into the depths of

God?

[13]

These were the conclusions and the attitude which we find enshrined in the original form of the Niceno-Constantinopolitanum, which goes no further than a simple paraphrase of John 15:26.

The fact, however, that Western Christians have taken the matter further, beginning chiefly (though not exclusively) with Augustine, and have raised--legitimately, I think--the question of the Second Person's part in the Spirit's origin, brings us to what I, and several other Orthodox theologians before me, feel that the ancient Semitic-Christian tradition sketched above and presupposed by Gregory can contribute to the discussion. Not to put too fine a point on it, this is the so-far-unaddressed question of the Spirit's role in the generation of the Son. What the old image of the Trinity as "family" reveals, together with the Synoptic baptismal narratives and Luke's account of the Incarnation, is a different Trinitarian taxis or model than the one we are all used to: not Father-Son-Spirit, but Father-Spirit-Son, or, and to borrow a phrase from Leonardo Boff, precisely an implied spirituque.

[14] It is this other taxis which I take to be effectively presupposed both by the Eastern epicleseis over the baptismal font and the eucharistic elements, and by the witness of the Eastern ascetico-mystical tradition, which is to say, that it has its roots in the very deepest and, I would argue, most primordial levels of Christian faith and practice as the latter have been known in the East since--well, since the beginnings of Christianity itself. Here, I think, we arrive at the real reasons--beneath and aside from the abstractions of divine monarchia, relations of origin, and of the properties of ousia and hypostasis, or of the purely canonical question of proper or improper additions to the ecumenical creed--for that visceral, almost instinctively negative Eastern reaction to the filioque which I mentioned at the beginning of this essay.

In a nutshell, the filioque as it stands, tout court, offends as it were the "inner ear" of Eastern Christian faith and practice, almost exactly in the way in which we would speak of the vertigo and nausea resulting from an injury to the fluids of the body's inner ear. Put more briefly still, the filioque strikes us Easterns as unacceptably lopsided. If it answers to a real need to explain in intra-Trinitarian terms the Son's sending of the Spirit, it does so at the expense of the Spirit's own active role and Person. The Latter becomes entirely passive and, in our eyes, this does not in consequence account adequately for the scriptural, liturgical, and--yes--mystical data of the Tradition which witness to His (or, if the reader prefers my ancient Syrians, Her) creative and generative power.

Fr. Boris Bobrinskoy has written very recently, and Fr. Dumitru Staniloae some time ago, of the need to restore a sense of the reciprocity in the relations between the Son and Holy Spirit.

[15] I would like to second that motion. As to the precise theological shape that reciprocity might take, or what formula might be found to express it adequately, I will not venture either to propose or to guess. Allow me instead to close not with my own words, but with those of a great Byzantine saint and mystic who wrote on the very eve of our millennial schism. St. Symeon the New Theologian (+ 1022) testifies here, as so often in his works, to personal transfiguration in the visio dei. It seems to me that his words might be taken as summing up and encapsulating the legitimate insights of both halves of the now sundered Christian ecumene:

What is the "image of the heavenly man" (1 Cor. 15:49)?

Listen to the divine Paul: "He is the reflection of the

Glory and very stamp of the nature" and the "exact image" of

God the Father (Heb. 1:3). The Son is then the icon of the

Father, and the Holy Spirit the icon of the Son. Whoever,

then, has seen the Son, has seen the Father, and whoever has

seen the Holy Spirit, has seen the Son. As the Apostle says,

"The Lord is the Spirit" (2 Cor. 3:7); and again: "The

Spirit Himself intercedes for us with sighs too deep for

words ... crying `Abba, Father!' (Rom. 8:26 and 15). He says

rightly that the Lord is the Spirit when He cries "Abba,

Father!", not that the Son is the Spirit--away with the

thought!--but that the Son is seen and beheld in the Holy

Spirit, and that never is the Son revealed without the

Spirit, nor the Spirit without the Son. Instead, it is in

and through the Spirit that the Son Himself cries "Abba,

Father!"

[16]

"On the Spirit" 11, from Christology of the Later Fathers, trans. E. R. Hardy (London: SCM Press; Philadelphia: Westminster Press, 1954), p. 200.

S. A. Harvey, "Feminine Imagery for the Divine: The Holy Spirit, the Odes of Solomon, and Early Syriac Tradition," St Vladimir's Theological Quarterly 37.2-3 (1993), pp. 111-139.

See, e.g., J. A. Jungman, The Early Liturgy to the Time of Gregory the Great, trans. F. A. Brunner (Notre Dame: University of Notre Dame Press, 1959), pp. 266-277. On the Holy Spirit in Syrian liturgy more intensively, see Sebastian P. Brock, The Holy Spirit in the Syrian Baptismal Tradition (Poona, India: 1979).

Homiliae selectae Mar Jacobi Sarugensis, ed. P. Bedjan (Paris: 1908), Vol. 4: 597, lines 8-13. I find it interesting that Jacob uses the verb skn here for the action of the Spirit, but the same root as noun, sekinto (equivalent to the Rabbinic Sekinah), appears exclusively elsewhere in reference to the Son--see 569:21, 570:13, and 602:20. Thus the Spirit in "abiding" or "dwelling" in the bread of the eucharist makes present the "Abiding" or "Dwelling" of God among us which is Christ, the Immanuel. Here thus I would myself discern an echo of the Nativity narratives in both Luke and Matthew--and perhaps of John 1:14 as well.

See W. Schneemelcher, ed., New Testament Apocrypha, 2nd ed., trans. R. McL. Wilson (Cambridge: Lutterworth Press; Louisville, Ky.: Westminster John Knox Press, 1991), Vol. 1: 177, and relatedly, A. F. J. Klijn, Jewish-Christian Gospel Tradition (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1992), pp. 39-40, 52-55.

In Schneemelcher, New Testament Apocrypha, Vol. II: 380-385. Note that H. Drijvers's introduction to the "Hymn," pp. 330-333, barely breathes the word "Gnostic," whereas G. Bornkam's introduction in the first edition thirty years before can speak of nothing else. The scholarship has shifted one hundred eighty degrees in the space of a generation, and for once it is for the better.

See S. P. Brock, "Clothing Metaphors as a Means of Theological Expression in Syriac Tradition," in Typus, Symbol, Allegorie bei den ostlichen Vatern und ihren Parallelen im Mittelalter, ed. M. Schmidt and C. F. Geyer (Regensburg: Pustet, 1982), pp. 11-38.

On these in Jewish tradition, see C. R. A. Morray-Jones, "Transformational Mysticism in the Apocalyptic-Merkabah Tradition," Journal of Jewish Studies 43 (1992), pp. 1-31, and I. Gruenwald, Apocalyptic and Merkavah Mysticism (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1980); and in Christian literature, A. DeConick, Seek to See Him: Ascent and Vision Mysticism in the Gospel of Thomas (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1996); J. A. McGuckin, The Transfiguration of Christ in Scripture and Tradition (Lewiston, N.Y.: Edwin Mellen Press, 1986); and A. Golitzin, "Temple and Throne of the Divine Glory: Purity of Heart in the Macarian Homilies," in Purity of Heart in Early Ascetic and Monastic Literature: Essays in Honor of Juana Raasch, O.S.B., H. Luckman and L. Kunzler, editors (Collegeville, Minn.: Liturgical Press, 1999), pp. 107-129.

Acts of Thomas 110:41-43, in Schneemelcher, Vol. 2: 382.

Homily 28.4, in Pseudo-Macarius: The Fifty Spiritual Homilies and the Great Letter, trans. G. Maloney (New York: Paulist Press, 1992), p. 185.

G. Quispel, Makarios, das Thomasevangelium, und das Lied von der Perle (Leiden: E. J. Brill, 1967); C. Stewart, "Working the Earth of the Heart": The Messalian Controversy in History, Texts, and Language to A.D. 431 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991).

See him against all analogies in "On the Spirit" 31-33, Christology of the Later Fathers, pp. 213-214.

"On the Spirit" 8, Christology of the Later Fathers, pp. 198-199.

L. Boff, Trinity and Society, trans. P. Burns (Maryknoll, N.Y.: Orbis Books, 1988), p. 205; cited in R. Del Colle, "Reflections on the Filioque," Journal of Ecumenical Studies 34.2 (1997), p. 211 and n. 24.

D. Staniloae, Theology and the Church, trans. R. Barringer (Crestwood, N.Y.: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1980), pp. 92-108; and B. Bobrinskoy, The Mystery of the Trinity: Trinitarian Experience and Vision in the Biblical and Patristic Tradition, trans. A. P. Gythiel (Crestwood, N.Y.: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1999), pp. 63-77, 279-316.

St. Symeon the New Theologian on the Mystical Life: The Ethical Discourses, trans. A. Golitzin, here Discourse III, in Vol. I: The Church and the Last Things (Crestwood, N.Y.: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1995), pp. 128-129.

Published in: Anglican Theological Review, 00033286, Summer2001, Vol. 83, Issue 3

.jpg)