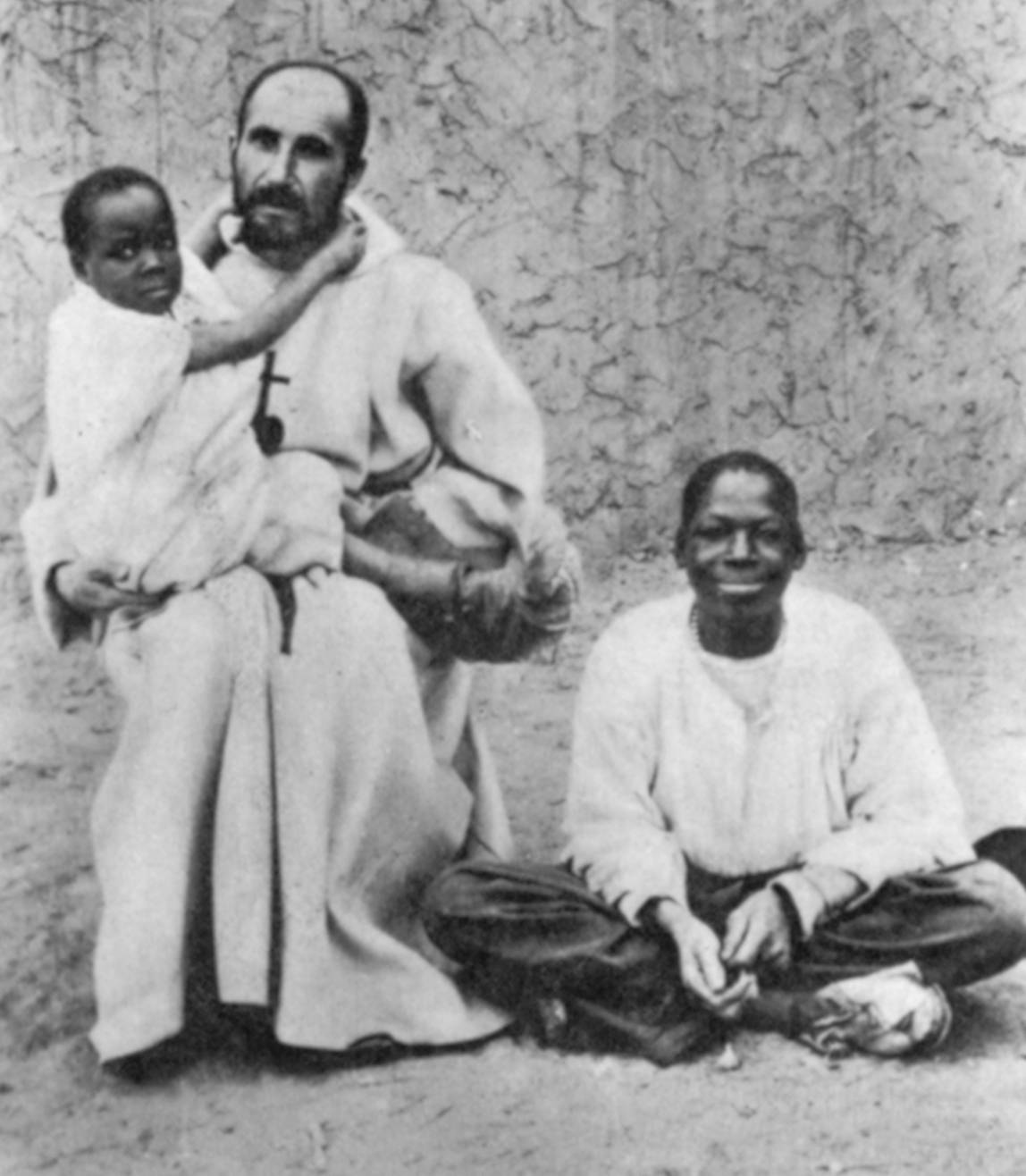

Charles de Foucauld is one of the reasons I was so keen to come to Peru. He had inspired me as a young monk to wish to rub shoulders with the poor. He had pushed me to help in the "Samaritans" in Hereford in my spare time, and gave me the impulse to go to Peru. This is just a small "thankyou" as my time in Peru comes to an end, even though I had to pinch Brother Ian Latham's work to make the gesture.

In every age, there are saints whom God uses to show the Church the path it should take. St Benedict inaugurated the Benedictine centuries; St Francis illuminated the Middle Ages; St Ignatius and St Charles Borromeo were signposts in the Counter Reformation.

We must be approaching a time in our history of immense importance because we have been given a number of great saints as well as Vatican II to help us on our way. Perhaps the two greatest saintswere those who lived hidden lives. One died in the obscurity of a Carmelite convent, while the other was killed by a bunch of drunken Touaregs in his Saharan hermitage, having achieved nothing he had set out to do. The messages they gave the Church by their lives were very simple.

As the Church takes on the world in the New Evangelisation, St Therese can teach us that great things can be achieved if we put ourselves completely at God’s disposition by humble obedience in little things, moment by moment;and Charles de Foucauld sows us by his example that we should identify with the poor and the outcast and become brothers and sisters to all. This is based, not on a wishy-washy liberalism but has the Incarnation as a foundation. In becoming man, Christ was united to all and each human being by the Holy Spirit, making all of us brothers and sisters in Christ. This is a reality to which we Christians must bear witness by our lives, and even by our deaths.

When the Coptic woman addressed her nation on television after her whole family had been killed by an ISIS bomb in a church on Palm Sunday this year and told those watching that she forgave the terrorists, did not want anything bad to happen to them and prayed for them, she impressed public opinion in Egypt and truly bore witness to Christ: the New Evangelization has already started!

my source: The Vision of the Gospel For Brother Charles, Jesus is the One who is present: this, I think, is something that strikes us immediately. It’s something we feel in Charles, himself, and which, in his company, influences our own approach to Jesus.

Presence is the answer to isolation. Two people, each one separate and alone, are walking through a park. One, tired, sits on a bench. Later, the other feels inclined to do the same and finds a space on the bench. After a while, they swap a few routine phrases (‘What a summer!’ -’Yes, isn’t it?...).Then one confides ‘I’m feeling so sad: my wife, you know ... died last month!..’ And the other replies ‘I’m so sorry, I know what you are feeling....’ And the next day they meet again... Physical proximity opens out into personal presence. In fact, there is no real presence except that of persons; and this presence of persons to one another is only realized through a recognition of the other and a giving of oneself to that other, leading to the shared recognition and self-giving of friendship, provided that the movement is brought to fulfillment.

God’s presence

Of course, God’s presence is something quite unique: an apparent absence that is really total presence. For with God, simply being and being preHe’s closer to us than we are to ourselves, as Augustine says. But, paradoxically, we aren’t, and in the main can’t be, aware of this, at least directly. The marvelous signs and the prophetic word, coupled with thesages’ reflections, are a first move towards closing this gap. But it’s only, I think, with the Incarnation that God becomes present for us. And it’s only through the gift of the Spirit that we can recognize this presence of God-with-us and respond to it, so that the all-present God becomes effectively present to us. For an unrecognized presence is not properly a presence: there needs to be mutuality. John’s gospel, in particular, reveals this presence in the full sense, and the wonders of it.

Presence of the Beloved

Charles, it is I think clear, was struck by this ‘presence’ of the Beloved. In fact, he was seized by it, and it becomes the dominant note of his spiritual path. At first, he finds this presence above all in the Blessed Sacrament. Jesus is ‘there’, in front of him; and so he can ‘talk’ with Jesus – speaking, listening, resting in silence... So he feels the urge to spend long moments simply ‘there’, present to ‘the presence’, present with love to the presence of Love.

A developing relationship

For Charles, this is the expression of an intensely personal relationship. And because personal it develops. If Jesus is present in the Sacrament, he’s also present in the word of the Gospels: there, and there alone, we can see him acting, hear his words, follow his journey... and so are stimulated to join him and walk with him. Most of his meditations are gospel meditations; and some of his texts, such as ‘Le modele unique’ are nothing but strings of gospel quotes, largely of Jesus’ words. For, as he says, to love is to imitate...

This personal relationship with Jesus’ presence in word and Sacramento grows, at Beni-Abbes in particular, into the recognition of Jesus’ presence in the person who comes, whoever that may be, and especially in ‘the least’. In fact, the Eucharistic presence and the Neighbour presence are explicitly connected: ‘the one who said ‘this is my body’ said ‘whatever you do to the least of my brothers and sisters you do to Me’ – no word of the gospel has more impressed me’... A decision at Tamanrasset Later, when in Tamanrasset, Charles is faced with the question: should he stay with the people, with the few local Touareg families, without the possibility of celebrating or reserving the Eucharist; or, on the contrary, should he return to Beni-Abbes, or somewhere further north, to have again the opportunity of the Mass with a server as then required, but leaving, perhaps permanently, the Touareg people whose lives he had come to share and which he alone could do? ‘It’s hard to spend Christmas without Mass’ (1907). How does he reason? ‘Formerly I tended to see on one side the Infinite, the holy Sacrifice, and on the other the finite, everything apart from God, and was always ready to sacrifice, anything to celebrate. Holy Mass. But there must have been a mistake in my reasoning here, for from the time of the apostles, the greatest saints have sometimes sacrificed the possibility of celebrating to works of spiritual charity, to make journeys and so on... It is good to live alone in the land [the Hoggar]; one can do things there, even though they are of no great importance, for one becomes ‘at home’ there – easily available to people and quite ‘ordinary’. (July 1907 to Mgr Guerin).

Praying as relationship with God

Simplicity, absolute simplicity – that is what marks Charles’ way of praying. As breathing for the body, so is praying for the soul. In fact, he makes this

comparison himself: breathing in is like receiving God, breathing out like giving back what he has given.

His basic approach can be summed up in the ‘formula’: loving attention to Jesus. We could add... to Jesus present, and supposing always, Jesus as Love incarnate. This, surely, is in the pure gospel tradition:

‘This is my Son, my Beloved, listen to Him’, ‘Remain in me.. in my Word... in my Love’

(John 15 and the whole of 1 John).

It is also in line with the way of Teresa of Avila and John of the Cross, whom Charles constantly read and recommended. Of course, Charles personalizes this gospel and Carmelite way of praying in his own fashion. It follows that we may wish to express it differently, in a manner personal to each of us. Charles explicitly allows for this (remember he was always expecting others to arrive and join him), saying ‘let each be guided by the Spirit’. But contact with Charles, through his writings, may well give us a new insight into the real meaning of praying. Each time I reread him, I feel this renewal in myself.

Simple means

As Charles’ approach to prayer is simple, so are the means that he employs. Firstly the gospel:

‘Find the time to read a few lines of the holy gospel each day.. for a certain time (it should not be too long)..meditate for a few moments on what you find... Youshould try to soak yourself in the spirit of Jesus by reading and rereading, meditating and remeditating the words and examples of Jesus. It should be like the drop of water falling steadily on the same, stone in the same place..’ (to Massignon, 1914).

Secondly the Eucharist: ‘The Eucharist is Jesus’, Jesus present, Jesus our food, Jesus our sacrifice. An outward ‘bodily’ sign which Charles found to be ‘an extreme delight, a great support, and strength’... (to Marie de Bondy 1914), but which he was ready to give up, if need be, in favour of the reality signified, Jesus himself as always present (he had just received permission to reserve the Sacrament after a long interval).

Thirdly, daily life and events:

‘Be sure that God will give you what is best for his glory, best for your soul, best for the souls of others... (to Massignon 1916 1st December).

Events, and especially people, are occasions for receiving the coming of Jesus, and for responding in living faith and the Spirit’s love.

These great ‘means’ or ‘moments’ are basically unchanging and always valid. But the little methods of praying are, for Charles, purely relative, and vary as needed, to suit the variety of situations and the changing spiritual psychology. Always simple, they become as Charles goes forward, simpler still. Always, too, there is a combination of vocal prayers – psalms, rosary, exclamations – with meditation, mainly on the gospel, and with contemplation

– simple loving attention to Jesus present. This last, contemplation, is for Charles, prayer in the full sense, the ‘end’ to which we are aiming. But he readily acknowledges that vocal prayer and gospel meditation are the normal supports of contemplation and the preparation for it. This approach is at once practical, starting from where we are, and goes to the heart of real prayer in all its depths.

Guided by the Holy Spirit

‘We should let ourselves be guided by the Holy Spirit’ (on John 14, 28-33; see OS 159). How to pray? How to act? In both cases the Holy Spirit is our one guide (on Mark 13,2; see OS 155-157).

Not only does he ‘inspire’ our praying, giving it life and aim, but he guides us to pray in this or thatway, at this or that moment of our lives. Charles is convinced of this and constantly returns to this theme. ‘To hear well the voice of the divine Spirit, the help of a wise director is good’. Notice the role attributed to the ‘director’: simply to help a person listen better to the Spirit’s voice. For as Charles adds, ‘It is for God himself to form for each our interior life, and not for us nor for other creatures: Father into your hands I commend my spirit’. This understanding makes Charles totally free: free in adapting and changing his own concrete way of praying, free also in envisaging whatever form of praying is most appropriate to this or that person at this or that moment. Free finally to have or not to have the help of a director according to availability. Charles had the ‘good fortune’ to have the Abbé Henri Huvelin as his spiritual guide, a priest supremely conscious of the unique ‘work’ of the Holy Spirit.

The Mission of Brother Charles

Charles’ early life is, clearly, that of a person searching for, and finding faith And his life continues to be, up till the end, a journey in faith (cf Lumen Gentium 56: Mary, precisely as model of the Church and her members, ‘advanced in her pilgrimage of faith’..). Having found the Truth in the person of the one Lover, to become his ‘Beloved’, he continues to search for the way ahead, but now in the light of faith, a ‘light’ that for him – as for us – often appears as ‘darkness’ (cf the ‘dark nights’ of faith’s journey according to John of the Cross, whom Charles constantly read, and advised others to read).

‘Does Jesus love me?.. I feel nothing.. I have to grip hard to pure faith.’

Vocation: not chosen but found.

Converted at the age of 28, Charles, in willing acceptance of the Abbé Huvelin’s ‘direction’( so ‘gentle and firm’, so open to the Spirit), spends three full – and to him long – years in search of his personal vocation. As he later says, a vocation is ‘not chosen but found’, and ‘once found to be embraced wholeheartedly.

And his vocation-search is in line with his faith-discovery: total. He wants, and needs to give his ‘all’ for the ‘All’ that he has received:

‘As soon as I knew that God existed, I knew that I could only live for Him’

(we can recognize, again, his affinity with the ‘all and nothing’ of John of the Cross).

Who is this God that Charles comes to know

...and wishes to live for? It is not the all-powerful Creator and just Judge (the popular image of God at the time), but the God who is Presence, the God who is Love: the God whom Charles encountered in his conversion experience, whom he later names as ‘Jesus-Caritas’, and whose mercies he sings in his ‘retreat of Nazareth’ of 1897. Charles is far from denying the

total Transcendence (he had found a pointer to this among the Muslims), but this transcendent God meets him and embraces him in the heart of human experience.

‘By his incarnation, the Son of God has... united himself with each and every human person’(Gaudium et Spes).

It’s these words of the Council that are spelled out in Pope John Paul’s first, programmatic, encyclical, and are continued in all the others: Jesus’ redemption, God the Father’s mercy, the Spirit’s uplifting and healing power are present at the root of all human experience, be it personal history, family life, work, social relations and institutions. We only need faith (of which we have so little) – faith like that of Mary – to become aware of this ‘presence’ and to correspond to it in our actions.

Where is God present?

In Nazareth... This is Charles’ great discovery. Visiting the Holy Land (at Huvelin’s suggestion), Charles is attracted irresistibly by Jesus’ life in Nazareth, but he will only discover little by little all its meaning for himself and his followers. He chooses to enter a Trappist monastery precisely because it is, for him, a ‘Nazareth’: a place of poverty and manual work in ‘imitation of Jesus’, a place of ‘sacrifice’ for Jesus. As we know, Charles left the monastery. While clearly expressing what he felt God’s will to be for himself at this critical moment, he entrusted the decision totally – as was his way – into the hands of the Abbot General and his Council.

A mistaken vocation?

Was Charles’ seven-year stay with the Trappists a case of mistaken vocation? No it was not a mistake; but it was incomplete, though only the experience itself made Charles and his community aware of this. For Charles learnt much as a Trappist: self-discipline, community life, the ways of prayer... But he failed to find the ‘abjection of Jesus’: hadn’t Jesus chosen ‘the last place’ (as he had heard the Abbe Huvelin say)?

God the worker of Nazareth

Charles had seen something of this ‘last place’ when asked to visit a sick man, a poor Armenian, who lived with his family in the hills near the monastery of Akbés.

It was this that drew him to go and live in Nazareth itself and to be a ‘workman’. For wasn’t Jesus ‘God the worker of Nazareth’? In fact, Charles lived and worked as a handyman for the local convent of Poor Clares, and while doing odd jobs for the community (his manual skills, as it turned out, were limited!), he spent the greater part of his time in prayer before the Blessed Sacrament, in meditation on the Gospels, and in writing copy-book after copy-book of gospel-based reflections (the majority of his writings are from this three-year period).

It was like a long retreat (his contact with the village people was limited), in which he explored the meaning of Nazareth: the meaning for Jesus, for

himself, and for the future ‘fraternity’ of Nazarene ‘brothers’ and ‘sisters’.

From the first Charles, surprisingly, envisaged founding communities. Surprisingly, for he felt called to the ‘hiddenness’ of Jesus’ Nazareth life; and he had absolutely no means of realizing his desires. But it was only after an internal struggle that he accepted an invitation from the Mother Abbess of the Poor Clares at Jerusalem, to ask for priestly ordination, once assured that it was compatible with the ‘humility’ of Jesus.

For the salvation of all.

Ordination, at the age of 42, is for Charles a turning point. Before, he had put all his energies into his personal relationship with Jesus. Now he thinks in terms of being Jesus for others: as his ordination notes affirm,

he now wishes to ‘join Jesus in his immolation for the salvation of all’

Being a brother or sister to one and all

‘You have one Father and you are all brothers and sisters.’

Charles quotes this text time and time again, and tries constantly to conform his actions to it. We can say, I think, that for Charles ‘brotherhood’ derives

from Jesus and extends to every person, covering all their needs at every level. Let us then look at this more closely.

With Charles, all begins, always, with Jesus

Jesus is ‘our beloved Brother and Lord’. The one who loves us and whom we love is – astonishingly –our Brother: astonishingly, for Charles first discovered him as God-with-us and as the Lord who gives and asks all. Our Brother because he is ‘one of us’ and because he ‘shares our human condition’ (cf Hebrews chapters 2 and 5 and Gaudium et Spes 22).

As we know, Charles is particularly struck by the fact that Jesus shares our Nazareth situation: our simple ordinariness, with its daily routine of work, monotony, and anonymity, as also the poverty and abjection of so many.

And it is as our Brother that Jesus is ‘obedient’ to the Father and ‘journeys’ towards the Father. An obedience in trust, a journey through suffering... that he calls us to ‘follow’. ‘I am ascending to my Father and to your Father’ (John 20:17): this movement

covers the whole of Jesus’ life, from his boyhood to his death and glorification (cf Luke 1:50, 9:51, 23:46). And it is precisely as our Brother that Jesus, ‘the firstborn among many brothers’ (Rm 8:30), draws us along with him, to share his life in our here-and-now and, in the end, his destiny. That is, as our Brother that he shares our life, in all its humanness, and, by so doing, invites us to share his life of sonship with the Father, so that we are with him ‘sons in the Son’ (St Augustine).

For Charles, Jesus as our Brother applies not only to Christians but also – and equally – to every person, whatever their religion or lack of it. Charles sees Jesus primarily in his Nazareth situation: he is among us as our brother. A brother first to those who are of his family, to those who recognize and accept him; but a brother equally to all those around, to each and every person in the ‘village’ and, risen from the dead, to each and everyone, everywhere, in each and every generation. A brother, moreover, who is present, walking with each person in their life journey. This truth, that Charles instinctively came to see, is, I think, a new discovery of our time. In fact, to my mind, it only comes to clear expression in the first encyclical of John Paul, his programme/encyclical Redemptor Hominis. Commenting on Gaudium et Spes 22, he declares:

‘with man – with each man without any exception whatever – Christ is in a way united, even when man is unaware of it’;

and again,

‘each one of the four thousand million human beings living on our planet has become a sharer in Jesus from the moment he is conceived’.

Let’s analyze ‘being a brother or sister’ It is, surely, based on a recognition of equality: of being equally human, of being of equal worth and so of having an equal dignity. This leads to an attitude of respect and to its practical corollary, an attitude of concern. The whole of Charles’ experience

in the Hoggar is a witness to his growth in this recognition of others, so different in appearance, in culture and in religion, as being his equals, and hence as being worthy of respect. ‘We are all brothers and sisters, and we hope one day to share the same heaven’ (1904).

Notice the two levels of being brothers and sisters: as humans, and as having the same destiny. Charles’ approach is

always to begin with the practical and obvious human needs, and to work ‘upwards’ to the cultural and the religious.

A young Touareg girl, as she then was, recalled long after, how she would enjoy visiting the Marabout, ‘He always smiled, and he never kept us waiting’.

A simple enough remark, but full of meaning. For Charles was working long hours on his Touareg dictionary, and he was a man of intense concentration and strict routine, never willing to waste a minute. Yet he was able to spare time to serve others.

No comments:

Post a Comment