“And in this he showed me a little thing, the quantity of a hazel nut, lying in the palm of my hand, as it seemed. And it was as round as any ball. I looked upon it with the eye of my understanding, and thought, ‘What may this be?’ And it was answered generally thus, ‘It is all that is made.’ I marveled how it might last, for I thought it might suddenly have fallen to nothing for littleness. And I was answered in my understanding: It lasts and ever shall, for God loves it. And so have all things their beginning by the love of God.

In this little thing I saw three properties. The first is that God made it. The second that God loves it. And the third, that God keeps it.”

― Julian of Norwich, Revelations of Divine Love

Catholics live in an enchanted world, a world of statues and holy water, stained glass and votive candles, saints and religious medals, rosary beads and holy pictures. But these Catholic paraphernalia are mere hints of a deeper and more pervasive religious sensibility which inclines Catholics to see the Holy lurking in creation. As Catholics, we find our houses and our world haunted by a sense that the objects, events, and persons of daily life are revelations of grace. (Andrew Greeley: The Catholic Imagination - Introduction)

Choosing to become Catholic has, in part, been a realization that the way I think and see the world is already deeply Catholic. While the Protestant imagination can be said to be dialectic, thinking in terms of either/or and stressing the unlikeness of things, the Catholic imagination is analogic — incarnational — seeing things in terms of likeness and unity, welcoming paradox. There is no schism between faith and reason, between the sacred and secular, between the natural and the numinous; God, the ground of all Being, inhabits each of these realms. All of reality is engraced.”

Having told us how, according to St Thomas Aquinas, we exist because we participate in God's own being, and that this makes us and all created things closer to Him than we are to anything else, Josef Pieper, the well-known German Thomist philosopher praises the very act of simply being. He writes:

A man who needs the unusual to make him "wonder" shows that he has lost the capacity to find the true answer to the wonder of being."

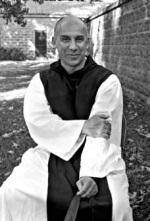

In 1958, Fr Louis, (Thomas Merton), experienced this in a direct mystical experience in Louisville. He wrote in his Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander:

“In Louisville, at the corner of Fourth and Walnut, in the center of the shopping district, I was suddenly overwhelmed with the realization that I loved all those people, that they were mine and I theirs, that we could not be alien to one another even though we were total strangers. It was like waking from a dream of separateness, of spurious self-isolation in a special world, the world of renunciation and supposed holiness… This sense of liberation from an illusory difference was such a relief and such a joy to me that I almost laughed out loud… I have the immense joy of being man, a member of a race in which God Himself became incarnate. As if the sorrows and stupidities of the human condition could overwhelm me, now I realize what we all are. And if only everybody could realize this! But it cannot be explained. There is no way of telling people that they are all walking around shining like the sun.”

However, even if everything and everyone that exists, at the point where he, she or it comes into existence, emerging from the love of God the Creator, shining with the normally invisible light of the Creator, sin has entered the world, weakening our wills, distorting our judgement and urging us to disobey God and harm our fellow creatures. It has also reached out to nature itself: there are orcs as well as elves in Middle Earth, Gollum as well as his distant cousins the hobbits; and machinery is creating ugliness, pollution and death.

Because God is intimately engaged with his creation, closer to each created being than any other created thing, the working of God's grace in weak and vulnerable human beings and in sinful situations is the stuff from which great Catholic novels are written. The country priest's encounter with a prostitute in the novel of Georges Bernanos in which the priest realises that "Grace is everywhere", the whisky priest with a sin unrepented who, alone among the priests, goes on ministering to the people in Mexico until he dies for his faith in "The Power and the Glory"; Scobie in "The Heart of the Matter"; "Silence", the story of the Jesuit missionary, Fr Sebastian Rodrigues, who gave in to Japanese pressure and stamped on the image of Christ, by the Catholic author Shusako Endo; even Sebastian in Evelyn Waugh's "Brideshead Revisited": all these show the Catholic authors' fascination with the workings of God's Grace where, according to the theologians and canon lawyers of the time, God's Grace should not be.

The presence of Sin in such a God-drenched world makes things difficult. From one point of view, it makes sin far more evil than if God were safely at a distance, and it makes God's mercy, his constant Love, a far tougher Reality than we can imagine: it is, after all, what created the universe. Nevertheless, it makes it more difficult spotting the Divine Will lurking under the surface of things because of the weakness and distortion in ourselves and the ugliness of sin around us. We must seek out what Father J-P de Caussade called the Sacrament of the Present Moment. He wrote:

We will finish with a poem of Gerald Manley Hopkins which sums everything up:

God's Grandeur

BY GERARD MANLEY HOPKINS

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man's smudge and shares man's smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs —

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

Source: Gerard Manley Hopkins: Poems and Prose (Penguin Classics, 1985)

”

Because God is intimately engaged with his creation, closer to each created being than any other created thing, the working of God's grace in weak and vulnerable human beings and in sinful situations is the stuff from which great Catholic novels are written. The country priest's encounter with a prostitute in the novel of Georges Bernanos in which the priest realises that "Grace is everywhere", the whisky priest with a sin unrepented who, alone among the priests, goes on ministering to the people in Mexico until he dies for his faith in "The Power and the Glory"; Scobie in "The Heart of the Matter"; "Silence", the story of the Jesuit missionary, Fr Sebastian Rodrigues, who gave in to Japanese pressure and stamped on the image of Christ, by the Catholic author Shusako Endo; even Sebastian in Evelyn Waugh's "Brideshead Revisited": all these show the Catholic authors' fascination with the workings of God's Grace where, according to the theologians and canon lawyers of the time, God's Grace should not be.

The presence of Sin in such a God-drenched world makes things difficult. From one point of view, it makes sin far more evil than if God were safely at a distance, and it makes God's mercy, his constant Love, a far tougher Reality than we can imagine: it is, after all, what created the universe. Nevertheless, it makes it more difficult spotting the Divine Will lurking under the surface of things because of the weakness and distortion in ourselves and the ugliness of sin around us. We must seek out what Father J-P de Caussade called the Sacrament of the Present Moment. He wrote:

Abandonment to Divine Providence Jean-Pierre de Caussade

“The duties of each moment are the shadows beneath which hides the divine operation.”“If we have abandoned ourselves to God, there is only one rule for us: the duty of the present moment.” There is not a moment in which God does not present Himself under the cover of some pain to be endured, of some consolation to be enjoyed, or of some duty to be performed. All that takes place within us, around us, or through us, contains and conceals His divine action.” Whatever connexion the divine will has with the mind, it nourishes the soul, and continually enlarges it by giving it what is best for it at every moment. It is neither one thing nor another which produces these happy effects, but what God has willed for each moment. What was best for the moment that has passed is so no longer because it is no longer the will of God which, becoming apparent through other circumstances, brings to light the duty of the present moment. It is this duty under whatever guise it presents itself which is precisely that which is the most sanctifying for the soul. If, by the divine will, it is a present duty to read, then reading will produce the destined effect in the soul. If it is the divine will that reading be relinquished for contemplation, then this will perform the work of God in the soul and reading would become useless and prejudicial. Should the divine will withdraw the soul from contemplation for the hearing of confessions, etc., and that even for some considerable time, this duty becomes the means of uniting the soul with Jesus Christ and all the sweetness of contemplation would only serve to destroy this union. Our moments are made fruitful by our fulfilment of the will of God. This is presented to us in countless different ways by the present duty which forms, increases, and consummates in us the new man until we attain the plenitude destined for us by the divine wisdom. This mysterious attainment of the age of Jesus Christ in our souls is the end ordained by God and the fruit of His grace and of His divine goodness.

We will finish with a poem of Gerald Manley Hopkins which sums everything up:

God's Grandeur

BY GERARD MANLEY HOPKINS

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man's smudge and shares man's smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs —

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast and with ah! bright wings.

Source: Gerard Manley Hopkins: Poems and Prose (Penguin Classics, 1985)

”

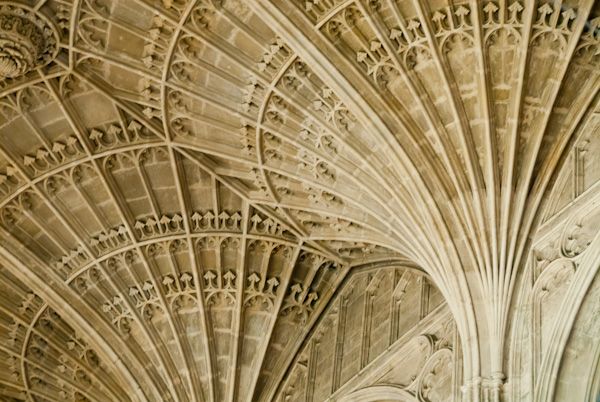

God helps us in our task. Even though God is present everywhere and in all circumstances, only waiting for our faithful response to discover Him, He also provides what the Irish call "thin" places, in which the divine Presence threatens to burst through the thin layer of the material world. Anywhere near the Blessed Sacrament is in danger of invasion. I have met too many converts who have been bould over by his Presence in the tabernacle before they have known what it was that hit them. Icons can have the same effect, like St Francis and the crucifix in the ruined chapel of St Damian's. Shrines are "thin" places, and Gregorian chant has been known turn the air thin. A field, a forest or a glen can do the job. And the Lord can take us by surprise. The modern world needs as many thin places as possible, and religion can weaken for lack of them. A monastery's main work can be to become a thin place for guests.

No comments:

Post a Comment