Introduction

Here are three articles on the monastic life, two Orthodox and one Catholic (pinched from its monastery website). I chose the article from the Monastery of Christ in the Desert in New Mexico because our Abbot Paul has been there, and he says that it is the monastery that he has seen most like our own Monastery of the Incarnation in Peru. However, having read the article, I would probably say that it is the most like what we want our monastery to be. We are alike in that we live and work within the monastery and, like them, we have no employees to help us.

Those of you well acquainted with monasteries will notice how similar the problems and questions on monastic life in the contemporary world are for Orthodox and Catholic monasteries.

Catholics will be surprised at the contrast between the Archbishop's balanced, intelligent and spiritually valuable treatment of monastic life and his fundamentally silly treatment of Catholicism. I remember an exclamation of a Russian Orthodox deacon from Minsk in Belarus, "Why is it that the Russians are so anti-Catholic when they don't know any Catholics!! Most of us have relatives who are Catholics and all of us have Catholic neighbours, and we know we can't make such sweeping judgements about them. The Russians, on the other hand, are doing it all the time!!"

The trouble with "establishment" Christianity, either in its Vatican or its Orthodox forms, is a tendency to turn God into a Canon lawyer who actually thinks like a canon lawyer.

Cardinal Burke thinks that Christ's teaching on marriage and divorce is identical to the Catholic laws that govern marriage and divorce: thus a change in law will also always be a change in teaching. He does not notice that Jesus was not giving a new version of the Law of Moses - it was a bit late for that because He was about to transcend it by His death and resurrection - but was applying to the problem of marriage and divorce his new commandment to love one another as he has loved us. It is about a self-giving, self-forgetting love that goes beyond law and has become the standard way of living for Christians, a law beyond law which transforms marriage. Like the Beatitudes, it aims for the maximum, nothing less than our sharing in the divine life of the Blessed Trinity: it is the new law of love, the law of the Cross, and not simply a stricter version of the Law of Moses: the Law of Moses remains for those who are still under its yoke, divorce and all.

The Orthodox recognise that the mercy that flows from the Cross of Christ and sets prisoners free is far greater than any law, whatever its provenance. That doesn't mean that laws are unimportant: they are to be observed under normal circumstances; but they cannot be allowed to create circumstances in which people are trapped by their sin so that whatever they do will cause grave harm. It is for the bishops to decide according to the pastoral circumstances. Normally, the laws must be obeyed, and this is called acribia. However, where people are trapped in their sin with no way out, then the bishops should resort to economia, because Christ saving us while we are yet in our sin is what the Christian Mystery is all about: God's mercy rides to the rescue.

However, those who are set free must, in their turn, follow a life marked by the same unlimited forgiveness and mercy by which they have been liberated themselves: hence, Christ's teaching on marriage and divorce.

If the Orthodox Church has much to teach us about how mercy takes preference over law in moral matters, the Catholic Church since Vatican II implicitly applies the same principle of economia over acribia in ecclesiology. I suggest that the Orthodox Church needs to do the same. Where some fall into the temptation to put law above mercy is to put too much emphasis on "canonical" when talking of the importance of "canonical communion": the actual existence of valid sacraments depends on there being "canonical", according to the canons. Thus, for many in the Russian Orthodox Church, the sacraments celebrated in the Kiev Patriarchate are simply meaningless ceremonies in a non-church. We would say that the celebration of the sacraments oblige those who celebrate, whether they are aware of it or not, to an extremely close ecclesial relationship with all others who celebrate the same sacraments, and that these ecclesial relationships should be regulated by canon law so that we may become what the sacraments want to make us; but sacramental life is more basic than legal relationships, being acts of Christ, just as mercy is more basic than law.

The Orthodox recognise that the mercy that flows from the Cross of Christ and sets prisoners free is far greater than any law, whatever its provenance. That doesn't mean that laws are unimportant: they are to be observed under normal circumstances; but they cannot be allowed to create circumstances in which people are trapped by their sin so that whatever they do will cause grave harm. It is for the bishops to decide according to the pastoral circumstances. Normally, the laws must be obeyed, and this is called acribia. However, where people are trapped in their sin with no way out, then the bishops should resort to economia, because Christ saving us while we are yet in our sin is what the Christian Mystery is all about: God's mercy rides to the rescue.

However, those who are set free must, in their turn, follow a life marked by the same unlimited forgiveness and mercy by which they have been liberated themselves: hence, Christ's teaching on marriage and divorce.

If the Orthodox Church has much to teach us about how mercy takes preference over law in moral matters, the Catholic Church since Vatican II implicitly applies the same principle of economia over acribia in ecclesiology. I suggest that the Orthodox Church needs to do the same. Where some fall into the temptation to put law above mercy is to put too much emphasis on "canonical" when talking of the importance of "canonical communion": the actual existence of valid sacraments depends on there being "canonical", according to the canons. Thus, for many in the Russian Orthodox Church, the sacraments celebrated in the Kiev Patriarchate are simply meaningless ceremonies in a non-church. We would say that the celebration of the sacraments oblige those who celebrate, whether they are aware of it or not, to an extremely close ecclesial relationship with all others who celebrate the same sacraments, and that these ecclesial relationships should be regulated by canon law so that we may become what the sacraments want to make us; but sacramental life is more basic than legal relationships, being acts of Christ, just as mercy is more basic than law.

Christ promised that the gates of hell shall no prevail against the Church. When this threatens to happen, due to our stupidity, our pride or because of a simple mistake or because we are in the wrong place at the wrong time, Christ doesn't cut off whole populations from the sacraments without them even knowing about it or turn away from people who invoke his Name as though they were not there, or cease to speak through his Word to people who are eagerly listening. The rules may have been broken, but God's mercy rushes in to heal the wound and to clear the way that has been blocked. The rules have to be obeyed as soon as it becomes possible; but, in the meantime, the gate to heaven is open to all who call on the name of the Lord, and even to those who do not know how to, because the Incarnation makes it possible for all.

Archbishop Arndt seems to believe that there was a mutual excommunication between East and West somewhere, at some time, perhaps in 1054, and all the sacraments in the West stopped working without anyone being aware of it, all preaching lost its force without any external effect to show that this was the case, and Christian holiness ceased to exist against all evidence to the contrary, because "salvation only exists within the Church" which can only mean the Orthodox Church.

As one Greek saint said, "Orthodoxy without charity is the religion of the devil," and any view of Christ who would render his sacraments null and void because of events which most people in the West were largely unaware of and very few could influence, is a diabolical view of Christ contradicted by every line of the Gospel.

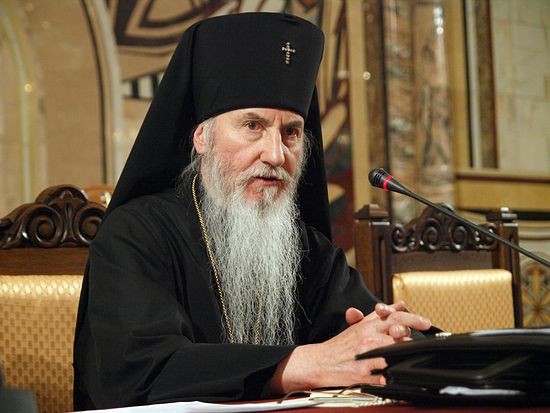

Catholics don't form a part of Archbishop Arndt's world, so it is not a view that does much harm in itself, although it helps explain why the Patriarch of Moscow must tread softly on ecumenical issues. However, Archbishop Arndt does know what he is talking about on monasticism; and I have no hesitation to recommend the following article to you.

As one Greek saint said, "Orthodoxy without charity is the religion of the devil," and any view of Christ who would render his sacraments null and void because of events which most people in the West were largely unaware of and very few could influence, is a diabolical view of Christ contradicted by every line of the Gospel.

Catholics don't form a part of Archbishop Arndt's world, so it is not a view that does much harm in itself, although it helps explain why the Patriarch of Moscow must tread softly on ecumenical issues. However, Archbishop Arndt does know what he is talking about on monasticism; and I have no hesitation to recommend the following article to you.

On Contemporary Monasticism: Interview with Archbishop Mark (Arndt)

my source: pravmir.com

One of the main problems faced by Christians and especially monastics today is that people are not used to restraining themselves, to enduring, or forcing themselves to do anything, to assume obligations, first and foremost to prayer.by KRISTINA POLYAKOVA | 31 JULY 2014

– I’ve lived my entire life outside of Russia and cannot objectively evaluate Russian monasticism. I became a monk having seen the sort of monastic life which was impossible to have under the Soviets, so I grew up on the experience of monasteries abroad—Serbian and those on Mt Athos. But I see that today, a great deal in society—in any society—changes, and is constantly evolving.

In the West, those who enter monasteries are faced with difficulties based on the fact that Western people are educated in individualism, a striving for being special in some way, and for this reason it is difficult to share a monastic residential cell with someone else—more than that, it is almost impossible. That is why I often bless people to share a monastic cell only after a certain time period, allowing a person to live in the monastery for a few years first. From what I’ve seen, monasteries are set up differently in Russia. Common monastic cells, of course, are necessary: people must relate to each other and they know how to. Compared to the West, Russian monastics face other kinds of difficulties. For example, here, it is difficult to give a novice a cell without a private shower. But this problem is resolved differently depending on where you look. There are monasteries where everything is modern—I’ve seen this in Greece. And there are places where this would be impossible—and thank God. Because young people need to learn simplicity, in relating with others, in daily life, in personal needs, etc. Without a doubt, it is different in every country. Every society has its idiosyncrasies and difficulties which must be overcome.

One of the biggest problems we endure in the West is the universal attachment to computers , telephones , of which newer and newer models are always being offered. Such things are necessary for us monastics, too, but in monasteries, the use of such devices must be regulated. You must understand: a person who is dependent on a computer cannot pray properly. The prayer of such a person will always be superficial. That is why using modern technology must be restricted to certain times, restricted for spiritual purposes. When a monk is busy fulfilling his many obediences, it can be difficult for him to tear away from them during divine services or domestic prayer. That is why it is especially important to teach young people how to remove themselves from daily cares.

– Maybe this is an awkward topic to discuss, but they say that there is a decline in monastic life in the West, especially among Catholics. Can you comment?

– Yes, there is a certain weakness, there are faults which must be battled and overcome, but I would not say it is in decline. Such things happen in every society, at any time, and we dare not fall into despair, into a paralyzed state. We must labor so that everything takes its proper place. The Lord gives us enormous opportunities. The possibilities we now have, especially in Russia, were few and far between in the past—it would be better to say that this is a very rare moment in time. We should therefore take action. Let us not be pessimistic, but look for the positive today, on this basis we can build something good.

As far as Catholic monasteries are concerned, there is indeed a decline. In my opinion this is partly a result of the general attitude of Western society which has strayed far from its Christian roots, but also a result of the fact that Roman Catholics do not have a solid foundation for spiritual life, because they abandoned the unity of the Church. Outside the Church there is no salvation.

– In your opinion, is it necessary for monastics to examine the regulations and way of life of other monasteries abroad? Or is there a model for establishing monastic life that everyone should follow?

– There can be no set models to follow in Christian life! If everything is standardized, Christianity, as a rule, dies out. One should not simply copy someone or something—everything is individual. For example, nature itself is completely different in Greece than in Russia. This leads to various needs and problems in the monasteries of these countries. But it is always useful to acquaint oneself with the ways and customs of other monasteries, learn something beneficial, or compare to one’s own ways. One must look at the positive aspects of different monasteries and communities and emulate them if there is a need.

– Vladyka, in your opinion, what is the main problem in the spiritual life of modern man, of a monk?

– One of the main problems faced by Christians and especially monastics today is that people are not used to restraining themselves, to enduring, or forcing themselves to do anything, to assume obligations, first and foremost to prayer. For some reason we stubbornly and persistently chase after sin, but good deed—alas! One of the ancient Church fathers said that prayer is more difficult than hewing rocks. A person today is raised to want everything right away, in abundance and cheaply. We have a consumerist society, everything is desired quickly and easily. But this doesn’t happen, since whatever is quick and easy to obtain is usually not appreciated. Only by obtaining something through great effort and persistence does a person value it highly. That is why persistence in prayer demands just such an approach, and, I think, this is one of the main obstacles faced by modern man, who is not used to achieving anything through patience and painstaking effort.

The Jesus Prayer is necessary for modern man! No Christian can get by without this prayer.

– Is the Jesus Prayer accessible to contemporary man?

– Of course. Moreover, it is absolutely crucial! Not only Christians in general but especially monastics need it. But there must be the desire and persistence, patience and love for Christ.

– The frescoes in Sretensky Seminary depict not only all the Russian saints, but even ascetics who have not yet been canonized, and there is a portrait of Feodor Dostoevsky along with Nikolai Gogol. You often speak of the influence Feodor Mikhailovich had on you, noting that he was one of the most Christian authors in Russian literature. What is your opinion of the role of literature and art on personal spiritual development?

– The Lord employs various means to bring us to know the truth. Good literature is one of these, bringing mankind towards Himself, it is one of the main means that turns the mind and heart to God. A Christian must know and read such writers as Dostoevsky—such reading enriches him spiritually. But when a person has already grown into the Church, there is no need for distraction by lay literature. It is better to read the Holy Fathers.

– Can monastics read lay literature? Is it beneficial?

– To a very limited degree, since if a person did not read literature before joining the monastery, it means he came unprepared. In general, it seems to me, a novice can read such things, but it is better for a monk to avoid it. A monk should be occupied with other things.

– If a monastery lacks a spiritually-experience guide, if there is no opportunity to reveal one’s thoughts to a spiritual father on a daily basis, what is to be done? In particular, this is the situation in some women’s convents.

– In my opinion, a spiritual father should be secondary in a convent—the abbess must be the one with whom a nun should share her thoughts. Or an abbess can appoint a senior nun to counsel the younger sisters. In any case, I think, it is better when a nun can talk to someone of the same sex, not to a man. A priest, a spiritual father is provided to take confession, which is somewhat different than revealing one’s innermost thoughts. Of course, an abbess can summon any spiritually-experienced person for the nuns to talk to. But such a person should display a great deal of tact and approach with caution so as not to interfere in the internal matters of the monastic community. In the Holy Land, two large convents are under my care. Of course, I do provide some counsel to the sisters, I hold discussions with them, but I always stress that at the end of the day, the abbess must rule. Unfortunately, in many monasteries they underestimate the importance of an abbess or elder nun.

– You mentioned that the monastic path must be chosen with great caution. What did you mean, exactly?

– It is necessary to maximally exclude one’s own will and accept God’s instead. In other words, to rely not on one’s own knowledge and limited mind, but on the fact that the heart will accept the Will of God, the heart will open up to the “dew” of the Holy Spirit which will allow the person to discern good from evil, what is beneficial and what is not.

– And the greatest aids for this are the Mysteries of Confession and Communion?

– Yes, primarily. I would say that this is a whole system within which a person should live and develop: prayer, the Mysteries, the revelation of thoughts, Confession, etc. We must emancipate ourselves from the state of that fragmentation which invaded human life as a result of the Western, Roman-Catholic false teachings. Fr Justin (Popovic) once said that the main sin of Catholicism is Papism, and the main sin of Protestantism is that each has its own pope, and that is even worse. This breakdown and emphasis on the human element are completely useless for salvation. It hinders spiritual development, since man is at the forefront, and in the end, there is no room for God. Even if he thinks that he is giving himself over to the Will of God, in reality it is not the case at all—it is self-delusion which will always be an obstacle to communion with God.

– How is one to tell what the Will of God is? One of the fathers of the Church said: “In order to fulfill the Will of God, one needs to know what it is, which is a great and difficult task.”

As long as a person is guided by his own will and his own mind, he cannot hear the call of God.

You understand, the most important thing in monastic life and in the life of a Christian in general is obedience. A person can attain true, genuine obedience only through humility and meekness. Only in this case will he be able to heed the voice of the Lord, to hear the Will of God. A closed, hermetic life demands great experience in obedience, which is possible specifically within a monastic community. In monastic life it is rare to go into seclusion very quickly, this is done only after many years of social life, during which a person suppresses his own ego and obtains the habit of obedience.

– How does one choose a monastery?

– If a person strives for monasticism, he must heed this call and make a conscious choice of a monastery to join. There are various kinds of monasteries . In the Orthodox world, each monastic community has its own identity and characteristics. One must choose according to the heart. Some like physical labor, others are drawn to contemplation. So in choosing a monastery, one should be oriented by individual preferences. For instance, [smiling] it took me eight years to choose.

– How should Christians react to the terrible epidemic of the genocide of our brothers and sisters in Christ in Syria, Metochia, Kosovo and Serbia? Is this active Islamization or the actions of radical extremists, bandits who only assume the mantle of Islam? His Holiness Patriarch Kirill of Moscow and All Russia, during a Liturgy in Christ the Savior Cathedral in Moscow read to his Russian flock the epistle of the Antiochian Patriarch, in which he painfully called to the whole world for help, stressing that the situation is at such a horrifying stage that help is needed not only through prayers to God, but in action. But in Christian society the reigning opinion is that we can help exclusively by prayer.

– I reject the expression “help exclusively by prayer.” That we Christians are only capable of prayer is a false notion. Of course, prayer is our foundation and greatest strength. But if we think that all we can do is pray, we will go astray. Yes, we must pray, but we must also understand that people are often forced by circumstances to soften one’s language. If the Antiochian Patriarch says this, he bases it on the experience of his own nation, where Christians and Muslims always lived in peace. I think that it is incorrect to say that there are only extremists at work there. Reading the Quran, you will see that all of this lies at the foundation of Islam. Extremism exists, of course. Other Eastern hierarchs openly state that they have known about this particular aspect of Islam all their lives. I often serve in Jerusalem . There, for instance, on the feast of the Holy Trinity, right next to the church a muezzin cries from his tower that they believe in the One God Who has no children, no Son and Holy Spirit, etc. He has no compunction to do so, thought these people are not really extremists. What is this? Open, unabashed propaganda against Christianity! They know full well what they do, spewing these slogans during the main Christian holiday of the Pentecost, the celebration of the birth of the Church Herself.

Islam is at its core anti-human. Look at Ramadan—this is the mortification of the human being, of the human body. I saw how people were taken to hospitals during their observance of Ramadan. All day they eat nothing, drink nothing even during baking heat, and at night the cram there stomachs to the point of losing consciousness—it is madness! One must look truth in the eye: this is all anti-human, it is directed against humanity.

Yes, there were times when Muslims tried to live in peace with their neighbors, they even acknowledged that we Christians are people, too. But for many, those times have passed, and now they reveal who they really are.

– In other words, when some say that what is happening in Syria and other fundamentally Christian nations, it is only political, not a religious war against Christianity, it is untrue? Regardless, can we say that the Christians who are murdered for their faith today are martyrs.

There is an intentional war being waged against Christians. Kosovo was the first in the list of such genocide from Christian territory. Then Chechnya. Understand what happened, a Christian nation was simply given away to the Muslims. The destruction of churches continues, tortures, wild fanaticism, murder. Kosovo, Chechnya, Syria, Egypt…

– The next goal for these people, whether they are extremists or not, is to declare Russian Muslim. What are we to do, strengthen our prayers?

– The most important thing is to be real Christians. This means constant participation in the Mysteries of the Church. If the Lord grants someone the crown of martyrdom, it means the person earned it and must accept it with dignity.

Practical Aspects of Observing Monastic Vows in an Urban Monastery

http://www.pravoslavie.ru/english/106172.htm Abbess Maria (Sidiropoulos)

Abbess Maria (Sidiropoulos). Photo: Stefmon.ru.

Speech by Abbess Maria (Sidiropoulos) of St. Elizabeth Convent in Buchendorf, Germany, of the German Diocese of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia, read at the round table “Particilarities of Monastic Life in Urban Monasteries” (St. Petersburg, Russia, August 8-9, 2017).

St. Ephraim the Syrian said “It is not tonsure and garb that makes the monk, but a heavenly desire and Divine living, because in this lies perfection in life.”

God’s commandments are the same for both monastics and laypersons.

Emulating Christ and deification are the meaning of earthly life for every person who calls himself a Christian. Asceticism, sorrows, deprivation, spiritual purity, obedience to God are all necessary not only for monastics but for laity. The life of every Christian is or most become parallel to the life of a monastic. But the laws of parallel lines prohibit them from intersecting…

Monastic tonsure is called a “second baptism,” during which hair is clipped, just as during the Mystery of Baptism. The vows made during monastic tonsure do not differ from those made during baptism, except, of course, the vow of chastity that monks and nuns make. But simply refusing married life does not comprise true and ideal chastity; ideal virginity applies not only to the body but to the soul.

The unmarried woman careth for the things of the Lord, that she may be holy both in body and in spirit, said Holy Apostle Paul (1 Corinthians 7:34). In order to observe a vow of chastity, one must fast, pray and avoid contact with the opposite sex.

All of us, monastics and laypersons, in daily prayer to the Lord, utter the words: “hallowed by Thy Name, Thy Kingdom come, Thy will be done, on earth as it is in Heaven.” We ask of God not wealth and domination over our neighbor, but “our daily bread,” and obedience to God’s will, so that the Lord would take reign in our hearts, which is achieved through perpetual repetition of the Jesus prayer. We likewise beseech Him “lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from the evil one,” that is, to preserve us from spiritual faltering. In other words, we can say that with these words monastics and laypersons ask for virtues which in principle comprise the monastic vows: obedience, poverty, virginity.

The monastery (Ησιχαστειριо), as a place of prayer, was originally connected to the concept of quietude. But this understanding extends to the sphere of spiritual peace. External quiet is required only for engendering the easy and quick achievement of inner silence. Regardless of whether the monastery is high in the mountains, in a distant wilderness or in the center of urban chaos, the monastery walls serves its purpose: it protects, defends the inner life of the monastery from external influences not only visibly, but spiritually.

If the monastery has walls but its gates remain open from dawn until dusk for visitors, then the world and temptations will pour into the monastery. And this is for material gain [from pilgrim donations—Trans.] which pale in comparison to that which we lose—the prayer that we accumulate and the mental concentration of the souls entrusted to us. So even if a monastery church is the only one in town, it is wise to limit visiting times.

Some monks who live in noisy cities are guardians of historic sites, for instance, in the Holy City of Jerusalem. But even there, though these sites are meant for veneration for people from all over the world, pilgrims and tourists, they must guard against mobs of visitors. The gates to such monasteries must remain closed for large portions of the day.

The conditions under which one can preserve one’s monastic vows in urban monasteries depend on many internal and external factors. The monastery’s regulations, especially in urban communities, must offer its residents time for seclusion for prayer and spiritual reading. If a monk is given this opportunity after evening prayer, when he has little strength after the day just passed, then he may succumb to slumber from exhaustion. In our convent, we find solitude for the daily prayer rule during the day, two hours before the beginning of vespers, while we still have strength, and this time allows us to refresh in our minds the life of a saint that will be commemorated in church that evening. In practice, this is an foretaste of the coming divine services, for the smooth transition to evening prayer. Adherence to one’s vows is not an external matter, for we are called upon to tend to our mouths and our eyes to achieve our goals, but the main condition and foundation of the fulfillment of vows, both in the city and in secluded hermitages is to recite the Jesus Prayer unceasingly, which is the basis upon which the monastic life is built.

Watch and pray, that ye enter not into temptation (Matthew 26:41), the Lord cautions us. As St. Isidore of Pelusium explains: “In these words of the Savior we must understand: pray so that temptation does not consume us. If the Savior had said what some people assume, that is, that you must pray lest you fall into any temptation at all, this would make no sense; for the Prophets, and the Apostles as well as other successful pious men all succumbed to great temptations. On the contrary, it might be impossible not to fall to temptation at all, but not to be conquered by them is in fact possible. So many of those who suffer ignorance in this matter can become inconsolable when facing hardship, meanwhile those who are guided by piety deflect misfortune not only by enduring temptations courageously but by pondering victory over them.”

When we utter the most sweet name of Jesus, then our mind, occupied with prayer, has neither the time nor the inclination to think of anything else, so that the very invoking of the name of Jesus Christ has the power to heal and purify the mind and heart from earthly bonds and protect us from failure and temptations.

Can anyone who finds himself in the midst of temptation not be tempted? No, of course not.

We are given examples of times when even during terrible persecutions and brutality against the Church of Christ, people would elect the path of monasticism. They lived and labored on par with laypersons in the cities, and such environments did not hinder them from fulfilling their monastic vows, for they were people of prayer, they burned with love and zeal for the ascetic life, for which they were glorified by the Church. In order the obtain such heartfelt fervor, people today must expend great effort, deny the temptations of the internet and constant flow of news from around the world, read Holy Scripture from a book, and not on a smart phone. Having a cell phone in your hand offers the temptation of reading the news of the day.

The monastic community, being an organism of the Holy Church, when healthy also possesses a robust immune system, just like the human body does. So a monk, as part of a monastic community and truly loving the monastic way of life, upon facing temptation can avoid the devil’s snares. He is helped, if you will, by his “monastic immunity,” which kills or resists the virus which attempts to infect his mind.

For all that is in the world, wrote the beloved disciple of Christ, is the lust of the flesh, and the lust of the eyes, and the pride of life (1 John 2:16). This triple evil must be defeated by chastity, poverty and obedience. That is why true monasticism demands the fulfillment of three vows: virginity, poverty and obedience.

The monastery, a place of prayer and silence but located in a noisy city is fated to develop in “climatic conditions” hostile to prayer, if it is not separated into areas accessible and inaccessible to visitors.

Although monasteries may all differ in external ways, all monasteries contain people who labor in common thought, interests and goals—Christ. Sooner or later they will see Christ in the image of their brother, they will access Him through ascetic labors, fasting and inner peace. They will also see Christ in the face of a pilgrim, with whom he may not even speak, but whom he will join in prayer. But many pilgrims think that if a monastic doesn’t talk to them, the monk or nun is cold, haughty and condescending. On the contrary, if a monastic doesn’t speak to pilgrims, he is passing them by physically but not spiritually; without allowing them entry into his mind, he makes them a place in his heart, for he will pray for them in his cell.

St. Barsonophius the Great says: “Not all who live in a monastery are monks, only those who do the work of a monk.” It is not the task of a monastic to befriend pilgrims, the main work of a monk is to live in obedience, prayer, adhering to his monastic vows. An elder once told a monk: “Better they call you unwelcoming and brusque than they praise you and you fall into the prelest’ [self-deception] of pride…”

Socializing with pilgrims can be very dangerous, especially early in one’s monastic life. Pilgrims may unwittingly become the instrument of the devil and remind and stoke in the soul of the monk memories of earthly life.

Striving for perfection and to fulfilling Divine commandments is the nourishment for a monastic, whose path ascends to one’s own personal Transfiguration. Laypersons who may have the same desires walk along a horizontal path, knowingly or not immersed in the cares of daily life.

I can share one experience, though our convent is not an urban one. We are blessed by God to be located in a town of 700 people, 20 kilometers from Munich, but our monastery is the only Orthodox convent in Germany. Our practices show that while performing missionary work in a foreign land, where interest in Orthodox Christianity is growing, although we rarely turn away pilgrims, still, from 12-2 pm and during cell prayers from 4-6 pm, we close our doors to visitors. Before vigil, we open the doors, and after compline we close again. Our nuns do not have blessing to commune with pilgrims.

Our residents do not have personal effects or phones. The nuns do not have blessing to receive gifts from pilgrims or relatives. If they get a package in the mail, they must bring it to me and receive blessing as to what to do with it. Knowing the weaknesses of each nun, I sometimes give my blessing to share the gifts with one nun or another, or keep something for herself and give the rest for common use. In order to prevent the sisters from becoming attached to material goods, they do not have blessing to bring anything into their cells without the abbess’ blessing. By our rule, the nuns cannot and do not have their own money. Going to town for groceries is done by the nuns only once a week, usually on Mondays.

In one of his lectures, our spiritual father [Archbishop Mark of Berlin and Germany] noted the difference between monastic vows and consumption in society today:

the vow of poverty contrasts with the desire for unlimited consumption of material goods;

the vow of chastity contrasts with sexual promiscuity;

the vow of obedience contrasts with the unlimited “personal freedom” which leads one to self-confirmation at any cost.

The goal of monasticism is achieved through the voluntary fulfillment of Christian commandments and the fundamental monastic vows, which are based on Holy Scripture:

the vow of poverty: Jesus said unto him, If thou wilt be perfect, go and sell that thou hast, and give to the poor, and thou shalt have treasure in heaven: and come and follow me (Matthew 19:21);

the vow of chastity: For there are some eunuchs, which were so born from their mother's womb: and there are some eunuchs, which were made eunuchs of men: and there be eunuchs, which have made themselves eunuchs for the kingdom of heaven's sake. He that is able to receive it, let him receive it (Matthew 19:12).

the vow of obedience: Then said Jesus unto his disciples, If any man will come after me, let him deny himself, and take up his cross, and follow me (Matthew 16:24).

In responding to God’s call to holiness, a contemplative monk fulfills an important role in the Church: he visibly witnesses in his life to the absolute priority of God to any created thing. The contemplative life, then, is the highest form of life that a Christian may live. It is called “the angelic life,” because our contemplation of God will continue in heaven and throughout all eternity. The life of the contemplative monk is already a foretaste of what is to come.

It is for this reason that Christ looks at a man with love and invites him to leave everything he has and to follow Him, to surrender radically to God in His mission for the salvation of mankind. (Mark 10:21). As the monk grows closer to God in love, he both draws God closer to the world and the world closer to God. Thus it comes about that we, too, even though we abstain from exterior activity, exercise nevertheless an apostolate of the very highest order, since we strive to follow Christ in the inmost heart of His saving mission.

Some website visitors read through this vocations section just to learn more about the monastic life at Christ in the Desert. They often wish to support us so that this life can be offered to a world greatly in need of such vocational opportunities, especially for the youth of today. You may do so here and be assured of our gratitude.

Our way of Life at the Monastery

The word monk (from the Greek μοναχός) refers to singleness of heart. A monk is single in several senses: by being celibate; by being single-minded or pure of heart in his dedication to God; and also by a desire for a simple life focused on the ‘one thing necessary’, as Jesus calls it, for eternal life. (Luke 10:42). In modern language a monk lives a life of integrity (wholeness) which he finds in relation to God. Importantly as well, a man desiring to become a monk does not enter an order, but a specific monastery. Thus the way of life or charism of a particular monastery is of greatest importance in the process of discernment.

Our Abbot Philip has declared:

That mirrors the fact that we must be relentless in our search for God every day. When men come to join our community, sometimes they are in for a rude awakening because our life is so very active. One person called it a daily marathon — and it is. Contemplative life does not mean sitting around and thinking about God all day long or even being on our knees and praying to God all day long. Rather, contemplative life for us is the challenge of remembering God in all that we do, say and are during the whole day — while we go about the normal things that monks do. Those normal things are common prayer, common work, common meals, meetings, private prayer, Scripture reading — and of course, some sleep!

The first thing that will strike any visitor to our monastery is that we pray constantly. Christ in the Desert is only one of a handful of monasteries of men in the Americas that still faithfully prays the full psalmody every week as we were instructed to by St. Benedict. (RSB 18:23). Beginning in the early morning, well before sunrise, the monk’s day of prayer begins, when all of nature is silent and the monk is free to meet the living God. Because we gather in our Abbey Church eight times a day to chant the Psalms and celebrate Mass, it is only natural that the monk is molded by this rhythm and his whole life becomes a prayer taken up into that of Christ and the Church far beyond the limits of his understanding. He thus stands before God with and on behalf of all people.

Secondly, at least four hours of the monk’s every weekday is spent in labor.

The Monastery of Christ in the Desert has no employees; all of its day to day work is done by the monastic community. The work engaged in by the monks any day might include cooking for the community, working in the vegetable gardens and on the grounds, painting cells, building walls, cleaning the guesthouse, working in the leather or tailor shops, clearing brush or making rosaries.

Thirdly, no guest leaves the Monastery of Christ in the Desert without noting the peace of the place and the joy of the community. The life of a faithful contemplative monk is joyfully lived in silence, prayer, work and contemplation while holding the deep needs of the world in his heart. The monk has the joy and support of living in the company of like-minded men, men who believe in prayer, who delight in serving their brothers and giving a witness to God’s love for mankind in the presence of our loving God.

How Can I Discern My Vocation?

The great mysteries of our faith, such as the Incarnation and the Trinity, are realities of profound beauty for the believer. A vocation, on the other hand, is not so mysterious. When speaking about a life of celibacy, Our Lord simply concludes: “He who is able to choose this, let him choose it.” (Matt. 19:12). A vocation is primarily a matter of choice — both ours and God’s. While God has called all Christians to holiness, He invites those who can accept a life of poverty, chastity and obedience to choose that life. Since it is an article of faith that none of us can undertake any good thing without the illumination and inspiration of the Holy Spirit, (Council of Orange, 529 A.D. Canon 7; John 15:15), we can know with assurance that any wholesome desire to live the monastic life is a gift of God.

So if at some level you feel drawn to the monastic life, there are three simple and practical things that you can do to determine that such a prompting is from God.

The first is to avail yourself of grace. Participate in the sacraments fully, attending daily Mass if you are able, and going to Confession frequently. Develop your prayer life. Thank God for His great kindness and the many gifts He has given you. Pray that He may help you to be as generous with your life as the Father was in giving His Son to us. And if you are really bold, ask God to bless you with a religious vocation.

Secondly, and in line with prayer, acknowledge God as a Father who truly loves you and wishes to shower you with graces. Since you are God’s child, humbly ask Him to make His will known to you. Be assured He will answer you, as He will do anything that we ask in Christ’s name. (John 14:14). The way God often speaks affirmatively to us is by granting us the fruits of the Holy Spirit in our lives: “love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control.” (Galatians 5:22).

Thirdly, when Our Lord called His first disciples He told them to “come and see” how he lived. So get to know monastic life. Read the Rule of St. Benedict (especially the Prologue and Chapter 58). Read the lives of saintly men and women whose lives may inspire you. Do not be afraid to reach out to the Vocation Director of the monastery and discuss with him your sense of your vocation. He will be able to encourage you and help you think over carefully what is involved. And a natural thing to do is to come and see how monks live. Arrange to spend some time at the monastery, experiencing the rhythm of prayer and work of the monks.

Stages of Formation

After the community comes to know a prospective candidate, he can be invited to live with us for a time in the cloister. Once in the monastery he will participate fully in the life of the community. This stage is referred to as the Observership, and it usually lasts for a month or two depending on each individual. Next comes Postulancy, which is a period of one year. Postulants wear a simple black tunic (cassock) and leather belt, and attend classes with the novices and participate fully in the work and prayer of the monastery.

If the Abbot and his Council determine the postulant is ready, the postulant may petition the community for entry to the novitiate. The Novice receives a new monastic name along with the black tunic, belt and short hooded scapular. During this period of formation he will study the Psalms, chant, liturgy, monastic history and the Rule of Saint Benedict.

During initial formation (Observership, Postulancy and Novitiate) the brothers live in the Old Cells and St. Antony’s Novitiate, both of which are north of the main dormitory cloister of the monastery proper. St. Antony’s has its own chapel where the brothers in initial formation do Lectio Divina (sacred reading) together in common, as well as a gym. In addition to weekly classes, on Sundays and Solemnities the brothers in formation go on hikes together, play volleyball or, in summertime, swim in the Chama River.

At the end of the one year of novitiate, when the Chapter — that is the monks in solemn vows — approves his petition, he may make Simple Vows for one year. At the time of his Simple Profession he is clothed with a black tunic and the long scapular of the professed monks. Classes for the simply professed cover a wide range of topics, including monastic and Church history, liturgy, patristics, philosophy and theology — allowing the monk to focus on a particular field of interest. Simple Vows are renewed each year, normally lasting for a period of three years.

The next stage in a monk’s life begins with his Solemn Profession. This commitment is for life. A Benedictine monk takes the vows of Obedience, Stability, and Conversion of Life. (RSB 58). It is at this point that the monk is given a long black choir robe, known as the Cuculla or Cowl, and assumes the responsibility of a chapter member, those who meet with the Abbot and vote on important matters in the monastery.

God has blessed our monastery with many wonderful vocations. It is perhaps because of our humble way of life and great fidelity to monastic tradition that we have attracted so many vocations. Currently we have six postulants, ten novices and six brothers preparing for Solemn Vows, and during the last 25 years we have made three monastic foundations (two in Mexico and one in Texas) and have helped revive four other contemplative monasteries.

Requirements

Test the spirits to see if they are from God.

–John 4:1

A vocation involves three parties: God who calls, the person who is called, and the Church which, guided by the Holy Spirit, determines whether the call is genuine. In this case, the Church is represented by the Abbot and Community. The testing of a vocation is an interplay of human and divine freedoms and, of necessity, takes some time.

There are, however, some objective criteria which are essential for a genuine vocation to our monastic life. A candidate must be male, single, Roman Catholic, and have received the Sacrament of Confirmation. He must be free from all binding obligations to his family and should not be in debt. In addition to this he should have lived a good, moral, Catholic life for a number of years and, normally, have shown that he is capable of earning his own living. Our life is joyful and rewarding, but it is also demanding, and therefore a candidate needs robust mental and physical health and an ability to live with others in community. Usually he will be between 20 and 35 years of age. He will need the intellectual ability to gain spiritual benefit from two hours of spiritual reading (Lectio Divina) a day and to be able to participate fully in the Mass and Office. Count Montalembert, in his Monks of the West (1872), said that to be a good monk one needs the characteristics of simplicity, generosity and a sense of humor. That still holds true today.

If you are interested in a vigorous monastic life with much prayer and emphasis on seeking God, if you are drawn to common prayer with brothers who are seeking God, if you can accept obedience and humility, then perhaps this is the community for you. If you would like information about joining the Monastery of Christ in the Desert, please contact our Novicemaster or fill in the inquiry form below.

The Role of Monks in the Church

from the Monastery (Catholic) of

Christ in the Desert.

All men and women are called to holiness, to be holy as God is holy. This is the source and goal of our human dignity. Some are called to serve the world by devoting all their energies to preaching the Gospel and tending the poor and needy. Some are called to bring new life into the world through married love. A few, however, are called in love to follow a road less traveled, to give themselves over to God alone in joyous solitude and silence, in constant prayer and willing penance. Such are the monks of the Monastery of Christ in the Desert, whose “principal duty is to present to the Divine Majesty a service at once humble and noble within the walls of the monastery” (Perfectae Caritatis §§ 7 & 9).

O that today you would listen to His voice.—Psalm 94When I am lifted up I shall draw all men to myself.—John 12:32I have loved you with an everlasting love.—Jeremiah 31:3

In responding to God’s call to holiness, a contemplative monk fulfills an important role in the Church: he visibly witnesses in his life to the absolute priority of God to any created thing. The contemplative life, then, is the highest form of life that a Christian may live. It is called “the angelic life,” because our contemplation of God will continue in heaven and throughout all eternity. The life of the contemplative monk is already a foretaste of what is to come.

It is for this reason that Christ looks at a man with love and invites him to leave everything he has and to follow Him, to surrender radically to God in His mission for the salvation of mankind. (Mark 10:21). As the monk grows closer to God in love, he both draws God closer to the world and the world closer to God. Thus it comes about that we, too, even though we abstain from exterior activity, exercise nevertheless an apostolate of the very highest order, since we strive to follow Christ in the inmost heart of His saving mission.

Some website visitors read through this vocations section just to learn more about the monastic life at Christ in the Desert. They often wish to support us so that this life can be offered to a world greatly in need of such vocational opportunities, especially for the youth of today. You may do so here and be assured of our gratitude.

Our way of Life at the Monastery

The word monk (from the Greek μοναχός) refers to singleness of heart. A monk is single in several senses: by being celibate; by being single-minded or pure of heart in his dedication to God; and also by a desire for a simple life focused on the ‘one thing necessary’, as Jesus calls it, for eternal life. (Luke 10:42). In modern language a monk lives a life of integrity (wholeness) which he finds in relation to God. Importantly as well, a man desiring to become a monk does not enter an order, but a specific monastery. Thus the way of life or charism of a particular monastery is of greatest importance in the process of discernment.

Our Abbot Philip has declared:

“Monastic life, as lived at Christ in the Desert, is relentless.”

That mirrors the fact that we must be relentless in our search for God every day. When men come to join our community, sometimes they are in for a rude awakening because our life is so very active. One person called it a daily marathon — and it is. Contemplative life does not mean sitting around and thinking about God all day long or even being on our knees and praying to God all day long. Rather, contemplative life for us is the challenge of remembering God in all that we do, say and are during the whole day — while we go about the normal things that monks do. Those normal things are common prayer, common work, common meals, meetings, private prayer, Scripture reading — and of course, some sleep!

The first thing that will strike any visitor to our monastery is that we pray constantly. Christ in the Desert is only one of a handful of monasteries of men in the Americas that still faithfully prays the full psalmody every week as we were instructed to by St. Benedict. (RSB 18:23). Beginning in the early morning, well before sunrise, the monk’s day of prayer begins, when all of nature is silent and the monk is free to meet the living God. Because we gather in our Abbey Church eight times a day to chant the Psalms and celebrate Mass, it is only natural that the monk is molded by this rhythm and his whole life becomes a prayer taken up into that of Christ and the Church far beyond the limits of his understanding. He thus stands before God with and on behalf of all people.

Secondly, at least four hours of the monk’s every weekday is spent in labor.

As the Rule says: “The Brothers should have specified periods for manual labor as well as for prayerful reading … when they live by the work of their hands … then they are truly monks,” (RSB 48).

The Monastery of Christ in the Desert has no employees; all of its day to day work is done by the monastic community. The work engaged in by the monks any day might include cooking for the community, working in the vegetable gardens and on the grounds, painting cells, building walls, cleaning the guesthouse, working in the leather or tailor shops, clearing brush or making rosaries.

Thirdly, no guest leaves the Monastery of Christ in the Desert without noting the peace of the place and the joy of the community. The life of a faithful contemplative monk is joyfully lived in silence, prayer, work and contemplation while holding the deep needs of the world in his heart. The monk has the joy and support of living in the company of like-minded men, men who believe in prayer, who delight in serving their brothers and giving a witness to God’s love for mankind in the presence of our loving God.

How Can I Discern My Vocation?

My words are addressed to you especially, whoever you may be, whatever your circumstances, who turn from the pursuit of your own self-will and ask to enlist under Christ…”(RSB: Prologue)

The great mysteries of our faith, such as the Incarnation and the Trinity, are realities of profound beauty for the believer. A vocation, on the other hand, is not so mysterious. When speaking about a life of celibacy, Our Lord simply concludes: “He who is able to choose this, let him choose it.” (Matt. 19:12). A vocation is primarily a matter of choice — both ours and God’s. While God has called all Christians to holiness, He invites those who can accept a life of poverty, chastity and obedience to choose that life. Since it is an article of faith that none of us can undertake any good thing without the illumination and inspiration of the Holy Spirit, (Council of Orange, 529 A.D. Canon 7; John 15:15), we can know with assurance that any wholesome desire to live the monastic life is a gift of God.

So if at some level you feel drawn to the monastic life, there are three simple and practical things that you can do to determine that such a prompting is from God.

The first is to avail yourself of grace. Participate in the sacraments fully, attending daily Mass if you are able, and going to Confession frequently. Develop your prayer life. Thank God for His great kindness and the many gifts He has given you. Pray that He may help you to be as generous with your life as the Father was in giving His Son to us. And if you are really bold, ask God to bless you with a religious vocation.

Secondly, and in line with prayer, acknowledge God as a Father who truly loves you and wishes to shower you with graces. Since you are God’s child, humbly ask Him to make His will known to you. Be assured He will answer you, as He will do anything that we ask in Christ’s name. (John 14:14). The way God often speaks affirmatively to us is by granting us the fruits of the Holy Spirit in our lives: “love, joy, peace, forbearance, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness and self-control.” (Galatians 5:22).

Thirdly, when Our Lord called His first disciples He told them to “come and see” how he lived. So get to know monastic life. Read the Rule of St. Benedict (especially the Prologue and Chapter 58). Read the lives of saintly men and women whose lives may inspire you. Do not be afraid to reach out to the Vocation Director of the monastery and discuss with him your sense of your vocation. He will be able to encourage you and help you think over carefully what is involved. And a natural thing to do is to come and see how monks live. Arrange to spend some time at the monastery, experiencing the rhythm of prayer and work of the monks.

A Prayer of Discernment–by Thomas Merton

My Lord God, I have no idea where I am going. I do not see the road ahead of me. I cannot know for certain where it will end. Nor do I really know myself, and the fact that I think that I am following your will does not mean that I actually am doing so. For I believe that the desire to please you does in fact please you, and I hope that I have the desire in all that I am doing. I hope that I will never do anything apart from that desire. And I know that if I do this you will lead me by the right road though I may know nothing about it. Therefore will I trust you always though I may seem to be lost and in the shadows of death. I will not fear, for you will not leave me to face the perils alone. Amen

Stages of Formation

After the community comes to know a prospective candidate, he can be invited to live with us for a time in the cloister. Once in the monastery he will participate fully in the life of the community. This stage is referred to as the Observership, and it usually lasts for a month or two depending on each individual. Next comes Postulancy, which is a period of one year. Postulants wear a simple black tunic (cassock) and leather belt, and attend classes with the novices and participate fully in the work and prayer of the monastery.

If the Abbot and his Council determine the postulant is ready, the postulant may petition the community for entry to the novitiate. The Novice receives a new monastic name along with the black tunic, belt and short hooded scapular. During this period of formation he will study the Psalms, chant, liturgy, monastic history and the Rule of Saint Benedict.

During initial formation (Observership, Postulancy and Novitiate) the brothers live in the Old Cells and St. Antony’s Novitiate, both of which are north of the main dormitory cloister of the monastery proper. St. Antony’s has its own chapel where the brothers in initial formation do Lectio Divina (sacred reading) together in common, as well as a gym. In addition to weekly classes, on Sundays and Solemnities the brothers in formation go on hikes together, play volleyball or, in summertime, swim in the Chama River.

At the end of the one year of novitiate, when the Chapter — that is the monks in solemn vows — approves his petition, he may make Simple Vows for one year. At the time of his Simple Profession he is clothed with a black tunic and the long scapular of the professed monks. Classes for the simply professed cover a wide range of topics, including monastic and Church history, liturgy, patristics, philosophy and theology — allowing the monk to focus on a particular field of interest. Simple Vows are renewed each year, normally lasting for a period of three years.

The next stage in a monk’s life begins with his Solemn Profession. This commitment is for life. A Benedictine monk takes the vows of Obedience, Stability, and Conversion of Life. (RSB 58). It is at this point that the monk is given a long black choir robe, known as the Cuculla or Cowl, and assumes the responsibility of a chapter member, those who meet with the Abbot and vote on important matters in the monastery.

God has blessed our monastery with many wonderful vocations. It is perhaps because of our humble way of life and great fidelity to monastic tradition that we have attracted so many vocations. Currently we have six postulants, ten novices and six brothers preparing for Solemn Vows, and during the last 25 years we have made three monastic foundations (two in Mexico and one in Texas) and have helped revive four other contemplative monasteries.

Requirements

Test the spirits to see if they are from God.

–John 4:1

A vocation involves three parties: God who calls, the person who is called, and the Church which, guided by the Holy Spirit, determines whether the call is genuine. In this case, the Church is represented by the Abbot and Community. The testing of a vocation is an interplay of human and divine freedoms and, of necessity, takes some time.

There are, however, some objective criteria which are essential for a genuine vocation to our monastic life. A candidate must be male, single, Roman Catholic, and have received the Sacrament of Confirmation. He must be free from all binding obligations to his family and should not be in debt. In addition to this he should have lived a good, moral, Catholic life for a number of years and, normally, have shown that he is capable of earning his own living. Our life is joyful and rewarding, but it is also demanding, and therefore a candidate needs robust mental and physical health and an ability to live with others in community. Usually he will be between 20 and 35 years of age. He will need the intellectual ability to gain spiritual benefit from two hours of spiritual reading (Lectio Divina) a day and to be able to participate fully in the Mass and Office. Count Montalembert, in his Monks of the West (1872), said that to be a good monk one needs the characteristics of simplicity, generosity and a sense of humor. That still holds true today.

If you are interested in a vigorous monastic life with much prayer and emphasis on seeking God, if you are drawn to common prayer with brothers who are seeking God, if you can accept obedience and humility, then perhaps this is the community for you. If you would like information about joining the Monastery of Christ in the Desert, please contact our Novicemaster or fill in the inquiry form below.

No comments:

Post a Comment