So what interested him was not systems, but persons and their meeting. Not God as a philosophical idea, not God as somehow an explanation for the order that we find in the world round us. I don’t think he spoke much about that. But about the need to meet God personally in our own lives.Xenia Luchenko, Michael Sarni | 15 July 2015

– Your Eminence, this year we mark the 100th anniversary of Metropolitan Anthony of Sourozh’s birth. People in Russia know him mostly through his books, recordings of his sermons and talks, and reminiscences of those Russians whose life he touched. But could we speak of Metropolitan Anthony contributing in a significant way to the preaching of the Gospel in the 20th century Britain? To what extent the British society was receptive to his message? Has he left a mark in the British culture? Or his message was mostly to the Russian émigré community?

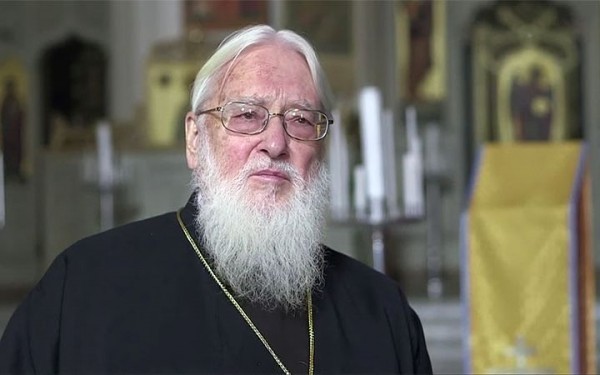

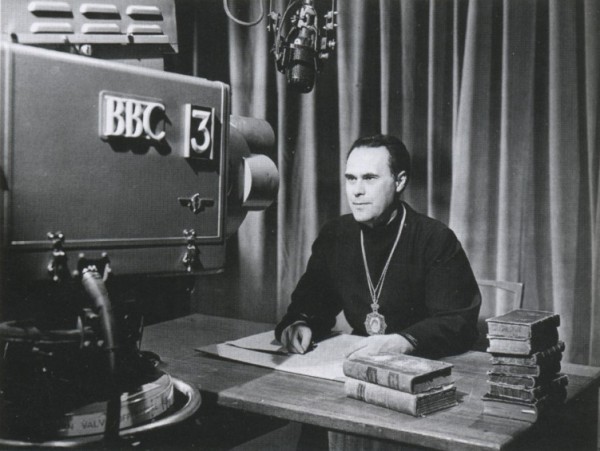

– Metropolitan Anthony made impact both on Russian émigré community in London and on the wider public. He was the first Orthodox figure in England, either from clergy or laity, who became widely known to the British public as a whole. Yes, there had been other Orthodox who were active in making contact with non-Orthodox. But Metropolitan Anthony particularly through his appearances on television was the first who established himself as an influential figure in the imagination of the British public at large. So certainly he made a contribution there. But he also made a contribution in building up the Russian parish in London which was under the jurisdiction of the Moscow Patriarchate (there was also Russian parish belonging to the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, Zarubezhnaya Tserkov). When Metropolitan Anthony took over the Moscow Patriarchal parish in London in the late 1940s, it was a small congregation of émigré Russians. He built it up into an active community mainly of English Orthodox. But then in the last years that Metropolitan Anthony was active, there was also a new influx of émigrés from Russia. Yes, his impact on the British public at large came first of all through his journeys around Britain to speak to different groups, then through his television appearances, and then through his books. And no other Orthodox has had that extent of influence on the popular level. Somehow his particular message spoke to people’s hearts.

– How would you assess the contribution made by the Russian Orthodox community, and Metropolitan Anthony in particular, towards the development of an English-language Orthodox service?

– In the Russian parish in London, Metropolitan Anthony was the first to use English on a regular basis. Certainly when he began his ministry in the late 1940s all the services held by Orthodox Christians in the British Isles would have been either in Greek or in Slavonic. Occasional English liturgies were organised by the Fellowship of St. Alban and St. Sergius, but these took place outside the framework of Orthodox parish life. When Metropolitan Anthony extended his work beyond London and built up a diocese, again, most of the parishes within his diocese were English-language. So it could be said he played a pioneering role in the use of English (not that at Ennismore Gardens in London there were ever liturgies exclusively in English, as there were in other parishes that came under his Episcopal care). However, he does not stand alone here. English has also been extensively used by the Orthodox parishes that belong to the Patriarchate of Antioch. They have one parish in London that is Arabic-speaking, but all their other parishes are with convert clergy and using English. Equally, there are within the Greek Archdiocese a number of parishes using English, but they are in a minority there. So we may say that Metropolitan Anthony was a pioneer in the use of the English language, though now his work does not stand alone.

– The liturgical style of Metropolitan Anthony combined a very personal conversation with God with boldness of a leader of the congregation, praying ‘for each and for all’. Did this style influence some of the young priests? Or it was a unique gift?

– Metropolitan Anthony celebrated the Liturgy with solemnity. Certainly, in Ennismore Gardens, though he was opposed to an excessive use of ceremonial. He said to me once that he was against what he called ecclesiastical pageantry. But he certainly celebrated the Divine Liturgy in a solemn way with the episcopal practices. He also had, yes, his own very personal style of celebrating. Usually, not with the book in his hand: he knew the service by heart. Often his eyes were closed when he celebrated. His manner of celebration to me and to many others conveyed an impression of powerful prayer. I felt he was not simply going through the established ritual, but that he prayed from the heart as he celebrated. Now how far he influenced others in celebrating the same way, I am not sure. It would be very difficult to assess. And Metropolitan Anthony, in the intonation of his voice, in his way of moving, he was not easily copied. It would, I think, have been a mistake for others to try and model themselves on what was a very personal style of celebration.

– Thank you. How did you meet Metropolitan Anthony? Which of his characteristic features, or subjects of your conversations, or some events, you most vividly remember? When his name is mentioned, what first comes to mind? Do you feel he has influenced you in any way?

– The first time I heard Metropolitan Anthony speak was, I think, at the annual conference of the Fellowship of St. Alban and St. Sergius in 1955. This was before I had become Orthodox. I must also have heard him sometimes when he visited Oxford, as he did with some regularity. I came to know him more personally at a later date. For certain period I used to go to him for confession. And certainly I have heard him speak on numerous occasions and have shared meals with him. And I would not say we were very close. Yet, I knew him not only from a distance, but fairly close at hand. What I remember, yes, are first of all his public addresses, but also his more personal conversation. Metropolitan Anthony was a person of high intelligence. I think, there is no doubt that he had an able mind. He had not been trained systematically in theology in sense that he had never been to an organised theological seminary and he had never studied theology in university. He had, however, been taught on a more personal level in Paris by Vladimir Lossky.

I found his public addresses impressive at the time. His delivery was very remarkable. I had the feeling (as many others have done) as I listened: here is something immensely exciting that he is telling us. Afterwards, however, I often found it difficult to remember exactly what he had said. He wove a kind of spell through his delivery. He spoke almost invariably without written text, without any notes. Most of his writings are in fact transcripts that have been edited to a greater or lesser degree of his addresses. I don’t think he ever sat down to write a book. Sometimes, the editorial work is rather small, and you can see features which would have been perfectly natural in a spoken address, but do not look so good on paper. The book of his which I find the clearest in having a definite argument, an explicit thread, is Meditations on a Theme. And interestingly I learnt from the publisher, Richard Mulkern, that he himself had done a lot of editorial work. In most of the other books far less work was done. And when you read his addresses on paper somehow the argument does not appear so coherent. That perhaps was a natural effect of speaking without notes. How far he prepared in advance what he was going to say I don’t know. But I think often as he spoke he moved from one topic to another, more on the personal connection or ideas, rather than following out a single argument. So often I do not remember exactly what he said. And yet, I find in my own pastoral work, in my preaching and in the advice that I give to people in confession or when counselling them, often things that Metropolitan Anthony said come back to my mind. Illustrations that he used. Particular points that he emphasized. And I find them very helpful. So his gift was perhaps intuitive than systematic. But his intuitions frequently were very perceptive. And it’s those, as it were, fragments that come back to my mind from what he said, which illuminate things for me afterwards.

– Metropolitan Anthony was above all a renowned preacher and missionary. While being no theologian in the strict sense of the word, he made use of the treasures of Christian theology in a creative way, which allowed some people, especially in Russia, to speak of the ‘theology of Metropolitan Anthony’. Which of his theological views are close to your own? Are there any on which you hold a different opinion?

– Certainly Metropolitan Anthony was not a systematic theologian, nor in any sense of the word an academic theologian. I see him as above all a theologian of the human person. In his preaching and in his guidance given face-to-face, one-to-one the element that he emphasized above all was personal encounter. We are to meet God personally. We are to relate to others as one living person to another. This I think was the underlying theme of his teaching. And he would insist on the need for us to be true to ourselves as persons. So what interested him was not systems, but persons and their meeting. Not God as a philosophical idea, not God as somehow an explanation for the order that we find in the world round us. I don’t think he spoke much about that. But about the need to meet God personally in our own lives. He was not interested in dogmas in the abstract, but in dogmas as a living expression of personal life. He was not particularly interested in Church history. His interests lay in the work of Christ today. So I see him in that way as a personalist theologian. Perhaps he was influenced in his youth by the existentialism that was fashionable in France in the middle of the 20th century. But if so, this was an influence that he had assimilated and internalized. So yes, if we are to speak of the theology of Metropolitan Anthony, then I think his message could be summed up that there is nothing more important than persons and their encounter. He himself used to speak of how once when he sat down to read the Gospel of St. Mark, after he had got to one of the early chapters, he suddenly felt that Christ was there before him in the room. And this sense of personal presence, so he claimed, continued throughout his life. And so personal presence – whether on a vertical plane between us and God, or a horizontal plane between us and one another – that to me was the heart of his experience and his message. ‘Be a real person’ – not that I heard him use that phrase – but I think that is what he taught me.

– Although Metropolitan Anthony was highly respected by many, there are widely different opinions regarding his work and legacy. What in your view might have been causes for that?

– Yes, he had difficulties with the Russian community at the cathedral in London towards the end of his life. There were tensions between the older group of English converts, people whom he had received into the Church from the 1950s onwards, and then the new Russians who came in large numbers after the fall of communism in the 1990s. And he was unable to resolve the tensions which arose there. So from that point of view he had to face difficulties at the end of his life certainly. And it could be said that he failed to solve the tensions. That had a reason. His successor Bishop Basil also failed. In the end most of the English converts have left Ennismore Gardens. When I go there now, I see very few of the people I know, but I see lots of young Russian women. And the group of converts whom Bishop Anthony brought into the Church, they have gone to the parishes that exist under the Deanery which is now in the Ecumenical Patriarchate. So there I could say that Bishop Anthony’s life was not simply a success story. If he had been younger and in better health, perhaps he could have overcome these tensions. But as it was he didn’t.

I think Bishop Anthony was at his best one-to-one. Or one him speaking to a large group. He was not really a committee man. Therefore he did not work easily in organised structures, I think, as I’ve said already, his forte was personal encounter. Yes, in his later years he built up various organised structures in the Diocese of Sourozh. Lot of time was spent preparing elaborate constitution for the diocese. But Bishop Anthony felt quite free to ignore that constitution if he wished to. So his strength was on the personal level, and I don’t think he worked so well through organisations. Now the main criticism that I would make of Bishop Anthony is that he would allow people to become colossally dependent upon him. They would idolise him. Perhaps that was not entirely his fault that they came to feel such ardent devotion towards him. But I felt there was something unhealthy here. It was too personal in the wrong sense, that they saw him almost as a god on earth. And he would allow people, particularly women, to become very closely dependent upon him. And then he would suddenly abandon them. I don’t think I am indulging here in malicious gossip, but I know a number of cases where he had spent a lot of time with people, particular people, and then suddenly he would cut off, not see them anymore, not respond to their letters or telephone calls. Now I don’t know why he allowed such a close relationship be built up and then abandoned them. But if I was to criticise his work, I would think there was the weakest point.

– Metropolitan Anthony envisaged a Local British Church. Are we now closer to the fulfilment of that vision?

– Not much closer. One important development that has happened is the establishment in Britain of an Orthodox Episcopal Assembly. Now such groups existed in other parts of the world quite a long time ago. Since 1960 in the United States there has been the Standing Conference of Orthodox Bishops (SCOBA). In France there had been Episcopal committees of various kinds, certainly from the 1970s. But we in Britain until a few years ago never had any structure whereby the different bishops of the various jurisdictions met together in a formal way. There would be informal friendly contacts among the bishops, among the jurisdictions, but there were no organised contacts. Then at the inter-Orthodox conference at Chambésy, it was back in 2009, it was said that in all parts of the world Episcopal committees should be set up. And for the first time we had such a committee in Britain. This has been a step forward, not of course anything like the creation of a local church. I don’t think that Metropolitan Anthony had particularly close relations with the other Orthodox jurisdictions. What he did was to develop a diocese, with its constitution of which I’ve been speaking, that perhaps might serve as a model. But I don’t think he was particularly concerned with building up practical contacts with the other jurisdictions. In fact he did not have very close or happy relations with Archbishop Athenagoras (Kokkinakis), Athenagoras II, or with his successor in the Archdiocese Thyateira, Archbishop Methodios. But I have every reason to believe that the present Archbishop Gregorios of Thyateira was always a good friend of Metropolitan Anthony. I think they got along quite well together. In the same way I don’t think he had particular contacts with the Russian Church in Exile, ROCOR. In fact when he first arrived, the relations were quite difficult. But the reconciliation between ROCOR and Moscow came after his time. So Metropolitan Anthony was primarily influential with the general public and within his own diocese, and particularly community in London. But I don’t think he was very prominent in inter-Orthodox work. Not that he was against it.

– And the last question, a very long one. The London Russian Cathedral of the Dormition of the Mother of God has in recent year become predominantly a Russian Diaspora parish. The departure of Metropolitan Antony has played a part, and so did the sharply increased numbers of the Russians living in Britain. And what about the current state of Orthodoxy in the UK? Are there many English-language parishes? Could we say that there are some traditions peculiar to the British Orthodoxy? Do the children of the people who joined the Orthodox Church remain Orthodox when they grow up? Are there many second- and third-generation Orthodox faithful? Is there an interest towards Orthodoxy among British people, and, if so, what kind of interest – a scholarly inquiry into theological and cultural legacy of the Orthodox Church, or a search for a Christianity beyond Protestantism?

– That is not so much one question as a whole series of questions. First of all, the development of the Russian Orthodox Cathedral of the Dormition in London into predominantly a Russia diaspora parish, that was a tendency that had already begun before Metropolitan Anthony died. Though it has developed much more since that time. I don’t think Metropolitan Anthony himself particularly confronted this problem of how to work specifically with the new emigration of Russians. But it had begun before he died. As for the situation of English-language Orthodoxy, there has undoubtedly been an enormous development in the last fifty years. For example, I was ordained deacon in 1965, priest in 1966. At that time in the whole of Orthodoxy in Britain there was, I think, only one other English Orthodox priest, Fr. Kyril Taylor in the Moscow Church with Bishop Anthony. And there was an English Orthodox deacon in the Polish Orthodox Church, Fr. Cyril Browne. I can’t remember if there were any other English converts who were clergy at that time. Certainly there were none in the Greek Archdiocese of Thyateira. Today out of about 200 Orthodox clergy in all the different jurisdictions in the British Isles at least a third are English converts. Perhaps, as many as 70 to 80. So there has been an undoubted growth in English Orthodox presence. And these English Orthodox clergy are to be found not only in the Sourozh Diocese of Metropolitan Anthony, or what is now the Deanery under Constantinople. They are to be found notably with the Antiochians, a few with the Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia, quite a large number with the Ecumenical Patriarchate Diocese of Thyateira. So on the level of clergy there’s been an undoubted growth.

In the fifty years that I’ve been serving in the Church, there has also been a great increase in the use of the English language. But this is uneven. I would say in the Greek Archdiocese there is still a need for much more English than is being used at present. Because the young people in the large Greek Cypriot parishes do not understand Greek. And so they rapidly lose interest in the Church, because in many of the central Greek parishes in London and elsewhere nothing is used but Greek. If the young people don’t understand, they say: well, this is for the old ones, but it says nothing to us. And they drift away. So yes, there is progress, much more English is being used, but I don’t think enough is being done. It is an interesting point that until quite recently in all the Orthodox parishes in London, and there must be over 40 of them, nowhere was the Liturgy being celebrated exclusively in English. Yes, a lot of English is used in Ennismore Gardens, but along with Slavonic. And elsewhere some English was used. Outside London, yes, there were purely English Orthodox parishes. Now there is one such parish in London itself, using the Anglican church of St. Botolph under the Antiochians. But it is a curious fact that in London we have lagged behind at the use of English language. If you were to go Paris, you would find quite a number of parishes using French, not just predominantly, but exclusively. So we have moved rather slowly here. But outside London, yes, there are plenty of English-language parishes, rather small for the most part. The large Greek parishes are still strongly Greek national. So things change, but they change only gradually.

You made a good point in asking what happens to the children of the converts – do they stay in the Church. I haven’t had enough experience of this to form a general judgment. My impression is that it varies very widely. And it is difficult to give a single reason why in some cases the children remain, and in other cases they don’t. And among the English Orthodox clergy who are converts sometimes the children have stayed with their priest father, in other cases – not. So there does not seem to be a single pattern. And certainly I cannot think of any magic solution for keeping young people in the Church. If we have a problem there, of course so do all other Christians. And we cannot as Orthodox say that we are exempt from the difficulties that the others face.

There is an interest in the Orthodoxy among British people. Surely a growing influence. But there are very many for whom Orthodoxy is strange and foreign. We’re bound to go a long way before we will be considered one of the firmly established Christian communities in this country. When people think of Christianity in Britain, very often they don’t think of the Orthodox. Yes, there is a scholarly interest in Orthodoxy. But there’s no doubt that for many British people discovery of Orthodoxy is being life-changing. What is it that attracts people to the Orthodox Church? Again, it will be hard to give a single answer. Sometimes the influence will come through personal contact. But for myself I may mention three things that drew me to the Orthodox Church. The first was the theological beauty of the Orthodox services and especially the Divine Liturgy. I say theological beauty because it was not just aesthetic, though I love Russian Church music. But my earliest contacts with the Orthodoxy were through the Church worship; that was what drew me. So the discovery of the Divine Liturgy in all its spiritual beauty and theological depth was the first thing that attracted me. But I was also drawn secondly to Orthodoxy by the tradition of inner prayer, and especially the use of the Jesus prayer, which has played a central part in my personal life. And the third element in Orthodoxy that influenced me was the sense of living tradition, the sense that is an unbroken continuity between Orthodoxy today and the past. In the West, various breaks came with the development of the papacy, scholasticism in the High Middle Ages, the Reformation, the Enlightenment… Encountering Orthodoxy I felt: here’s the Church that still remains patristic, that has not known Scholasticism or Middle Ages in the Western sense; that has only been peripherally affected by the controversies of the Reformation. It is now being affected by the Enlightenment and secularism, yes, certainly. But I felt in Orthodoxy: here is a Church in living continuity with the Church of the apostles, of the martyrs. I was very impressed by the stories of persecutions in Russia in the 1920s and 1930s, and the fidelity of the Orthodox people under persecution in Russia. Yes, Church of the apostles, the martyrs, of the early Fathers, of the Ecumenical Councils. Yet, I felt in Orthodoxy: this is not something archaeological, or merely result of scholarly enquiry, but it is a living heritage in which the whole people of God share. So those three things drew me to Orthodoxy: the Divine Liturgy, the inner prayer and a sense of living continuity of tradition. I can’t speak for others.

Source: http://www.pravmir.com/metropolitan-kallistos-no-other-orthodox-has-had-that-extent-of-influence-on-the-popular-level/#ixzz3gCMG2Oh4

PLEASE LISTEN TO THIS VIDEO

Archbishop Anthony Bloom was one of the most charismatic persons I have ever met. When he spoke, it seemed that it came from his own experience of Holy Tradition - he was a holy man.

No comments:

Post a Comment