This article is an excerpt from The Wellspring of Worship by Jean Corbon

Jean Corbon was the principal author of the fourth and final part of the Catechism of the Catholic Church, "Christian Prayer. He served as translator and theologian at the Second Vatican Council, and was active and influential in ecumenical efforts. A native of Paris, Father Corbon was a member of the Dominican community of Beirut, Lebanon, and a priest of the Greek-Catholic eparchy of Beirut.

He was a favourite theologian of Joseph Ratzinger, and his influence in the Catechism goes beyond the section he directly wrote/ The section on our participation in the Christian Mystery which introduces the theme of the sacraments, while not having been written by him, is really his theology. He died in 2001.

If we consent in prayer to be flooded by the river of life, our entire being will be transformed; we will become trees of life and be increasingly able to produce the fruit of the Spirit: we will love with the very Love that is our God. It is necessary at every moment to insist on this radical consent, this decision of the heart by which our will submits unconditionally to the energy of the Holy Spirit; otherwise we shall remain subject to the illusion created by mere knowledge of God and talk about him and shall in fact remain apart from him in brokenness and death. On the other hand, if we do constantly renew this offering of our sinful hearts, let us not imagine that our New Covenant with Jesus will be a personal encounter pure and simple. The communion into which the Spirit leads us is not limited to a face-to-face encounter between the person of Christ and our own person or to an external conformity of our wills with his. The lived liturgy does indeed begin with this "moral" union, but it goes much further. The Holy Spirit is an anointing, and he seeks to transform all that we are into Christ: body, soul, spirit, heart, flesh, relations with others and the world. If love is to become our life, it is not enough for it to touch the core of our person; it must also impregnate our entire nature.

To this transformative power of the river of life that permeates the entire being (person and nature), the undivided tradition of the Churches gives an astonishing name that sums up the mystery of the lived liturgy: theosis or divinization. Through baptism and the seal of the gift of the Holy Spirit we have become "sharers of the divine nature" (2 Pet 1:4). In the liturgy of the heart, the wellspring of this divinization streams out as the Holy Spirit, and our individual persons converge in a single origin. But how is this mysterious synergy to infuse our entire nature from its smallest recesses to its most obvious behaviors? This process is the drama of divinization in which the mystery of the lived liturgy is brought to completion in each Christian.

The Mystery of Jesus

To enter into the name of the holy Lord Jesus does not mean simply contemplating it from time to time or occasionally identifying with his passionate love for the Father and his compassion for men. It also means sharing faithfully and increasingly in his humanity, in assuming which he assumed ours as well. In our baptism we "put on Christ" in order that this putting on might become the very substance of our life. The beloved Son has united us to himself in his body, and the more he makes our humanity like his own, the more he causes us to share in his divinity. The humanity of Jesus is new because it is holy. Even in its mortal state it shared in the divine energies of the Word, without confusion and in an unfathomable synergy in which his will and human behavior played their part. Jesus is not a divinized man; he is the truly incarnated Word of God.

This last statement means that we need not imitate, from afar and in an external way, the behavior of Jesus as recorded in the Gospel, in order thereby to effect our own divinization and become "like God"; self-divinization is the primal temptation ever lurking in wait. On the contrary, it is the Word who divinizes this human nature, which he has united to himself once and for all. Since his Resurrection his divinehuman energies are those of his Holy Spirit, who elicits and calls for our response; in the measure of this synergy of the Spirit and our heart, our humanity shares in the life of the holy humanity of Christ. To enter into the name of Jesus, Son of God and Lord, means therefore to be drawn into him in the very depths of our being, by the same drawing movement in which he assumed our humanity by taking flesh and living out our human condition even to the point of dying. There is no "panchristic" pseudo-mysticism here, because the human person remains itself, a creature who is free over against its Lord and God. Neither, however, is there any moralism (a further error that waits to ensnare us), because our human nature really shares in the divinity of its Savior.

"Man becomes God as much as God becomes a man", says Saint Maximus the Confessor. [1] Christian holiness is divinization because in our concrete humanity we share in the divinity of the Word who married our flesh. The "divine nature" of which Saint Peter speaks (2 Pet 1:4) is not an, abstraction or a model, but the very life of the Father, which he eternally communicates to his Son and his Holy Spirit. The Father is its source, and the Son extends it to us by becoming a man. We become God by being more and more united to the humanity of Jesus. The only question left, then since this humanity is the way by which our humanity will put on his divinity–is this: How did the Son of God live as a man in our mortal condition? The Gospel has been written precisely in order to show us "the mind of Christ Jesus" (Phil 2:5); [2] it is this mind with which the Holy Spirit seeks to fill our hearts.

According to the spirituality of the Church and according to the gifts of the Spirit given to every one, each of the baptized lives out more intensely one or other aspect of the mind of Christ; at the same time, however, the mystery of divinization is fundamentally the same in all Christians. Their humanity no longer belongs to them, in the possessive and deadly sense of "belong", but to him who died and rose for them. In an utterly true sense, all that makes up my nature–its powers of life and death, its gifts and experiences, its limits and sins–is no longer "mine" but belongs to "him who loved me and gave himself up for me". This transfer of ownership is not idealistic or moral but realistic and mystical. As we shall see, the identification of Jesus with the humanity of every human person plays a very large part in the new relationship that persons establish with other men; but when the identification is willingly accepted and when our rebellious wills submit to his Spirit, divinization is at work. I was wounded by sin and radically incapable of loving; now Love has become part of my nature again: "I am alive; yet it is no longer 1, but Christ living in me" (Gal 2:20).

The Realism of the Liturgy of the Heart

The mystical realism of our divinization is the fruit of the sacramental realism of the liturgy. Conversely, evangelical moralism, with which we so often confuse life according to the Spirit, is the inevitable result of a deterioration of the liturgy into sacred routines. But when the fontal liturgy, which is the realism of the mystery of Christ, gives life to our sacramental celebrations, in the same measure the Spirit transfigures us in Christ.

The Fathers of the early centuries tell us that "the Son of God became a man, in order that men might become sons of God". The stages by which the beloved Son came among us and united himself to us to the point of dying our death are the same stages by which he unites us to him and leads us to the Father, to the point of making us live his life. These stages of the one Way that is Christ are shown to us in figures in the Old Testament; Jesus fulfilled the prefigurations. The stages are creation and promise, Passover and exodus, Covenant and kingdom, exile and return, restoration and expectation of the consummation. The two Testaments inscribed this great Passover of the divinizing Incarnation in the book of history. But in the last times the Bible becomes life; it exists in a liturgical condition, and the action of God is inscribed in our hearts. Knowledge of the mystery is no longer a mental process but an event that the Holy Spirit accomplishes in the celebrated liturgy and then brings to fulfillment by divinizing us.

But it is not enough simply to understand the ways in which Christ divinizes us; the primary thing is to be able to live them. At certain "moments" the celebrated liturgy gives us an intense experience of the economy of salvation, which is divinization, in order that we may live it at all "times", these new times into which it has brought us. According to the Fathers of the desert, either we pray always or we never pray. But in order to pray always we must pray often and sometimes at length. In like manner (for we are dealing with the same mystery), in order to divinize us the Spirit must divinize us often and sometimes very intensely. The economy of salvation that emerges from the Father through his Christ in the Holy Spirit expands to become the divinized life that Christians live in the Holy Spirit, through the name of Jesus, the Christ and Lord, in movement toward the Father. But the celebration of the liturgy is the place and moment in which the river of life, hidden in the economy, penetrates the life of the baptized in order to divinize it. It is there that everything that the Word experiences for the sake of man becomes Spirit and life.

The Holy Spirit, Iconographer of Divinization

In the economy of salvation everything reaches completion in Jesus through the outpouring of the Holy Spirit; in the liturgy as celebrated and as lived everything begins through the Holy Spirit. That is why at the existential origin of our divinization is the liturgy of the heart, the synergy in which the Holy Spirit unites himself to our spirit (Rom 8:16) in order to make us be, and show that we are, sons of God. The same Spirit who "anointed" the Word with our humanity and imprinted our nature upon him is written in our hearts as the living seal of the promise, in order that he may "anoint" us with the divine nature: he makes us christs in Christ. Our divinization is not passively imposed on us, but is our own vital activity, proceeding inseparably from him and from ourselves.

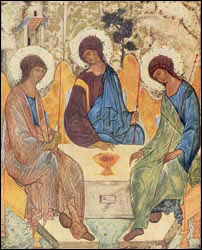

When the Spirit begins his work in us and with us, he is not faced with the raw, passive earth out of that he fashioned the first Adam or, much less, the virginal earth, permeated by faith, that he used in effecting the conception of the second Adam. What the Spirit finds is a remnant of glory, an icon of the Son: ceaselessly loved, but broken and disfigured. Each of us can whisper to him what the funeral liturgy cries out in the name of the dead person: I remain the image of your inexpressible glory, even though I am wounded by sin!" [3] This trust that cannot be confounded and this Covenant that cannot be broken form the space wherein the patient mystery of our divinization is worked out.

The sciences provide grills for interpreting the human riddle, but when these have been applied three great questions still remain in all that we seek and in all that we do: the search for our origin, the quest for dialogue, the aspiration for communion. On the one hand, why is it that I am what I am, in obedience to a law that is stronger than I am (see Rom 7)? On the other, in the smallest of my actions I await a word, a counterpart who will dialogue with me. Finally, it is clear that our mysterious selves cannot achieve fulfillment on any level, from the most organic to the most aesthetic, except in communion. These three pathways in my being are, as it were, the primary imprints in me of the image of glory, of the call of my very being to the divine likeness in which my divinization will be completed. The Holy Spirit uses arrows of fire in restoring our disfigured image. The fire of love consumes its opposite (sin) and transforms us into itself, which is Light.

We wander astray like orphans as long as we have not accepted him, the Spirit of sonship, as our virginal source. All burdens are laid upon us, and we are slaves as long as we are not surrendered to him who is freedom and grace. And because he is the Breath of Life, it is he who will teach us to listen (we are dumb only because we are deaf); then, the more we learn to hear the Word, the better we shall be able to speak. Our consciences will no longer be closed or asleep, but will be transformed into creative silence. Finally, Utopian love and the communion that cannot be found because it is "not of this world" are present in him, the "treasure of every blessing", not as acquired and possessed but as pure gift; our relationship with others becomes transparent once again. This communion of the Holy Spirit is the master stroke in the work of divinization, because in this communion we are in communion also with the Father and his Son, Jesus (2 Cor 13:13; Jn 1:3), and with all our brothers.

Following these three pathways of the transfigured icon, we are divinized to the extent that the least impulses of our nature find fulfillment in the communion of the Blessed Trinity We then "live" by the Spirit, in oneness with Christ, for the Father. The only obstacle is possessiveness, the focusing of our persons on the demands of our nature, and this is sin for the quest of self breaks the relation with God. The asceticism that is essential to our divinization and that represents once again a synergy of grace consists in simply but resolutely turning every movement toward possessiveness into an offering. The epiclesis on the altar of the heart must be intense at these moments, so that the Holy Spirit may touch and consume our death and the sin that is death's sting. Entering into the name of Jesus, the Son of God and the Lord who shows mercy to us sinners, means handing over to him our wounded nature, which he does not change by assuming but which he divinizes by putting on. From offertory to epiclesis and from epiclesis to communion the Spirit can then ceaselessly divinize us; our life becomes a eucharist until the icon is completely transformed into him who is the splendour of the Father.

Address of His Holiness Pope Francis at the Divine Liturgy of the Patriarchal Cathedral of St. George (30.11.14)

When I was the Archbishop of Buenos Aires, I often took part in the celebration of the Divine Liturgy of the Orthodox communities there. Today, the Lord has given me the singular grace to be present in this Patriarchal Church of Saint George for the celebration of the Feast of the holy Apostle Andrew, the first-called, the brother of Saint Peter, and the Patron Saint of the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

Meeting each other, seeing each other face to face, exchanging the embrace of peace, and praying for each other, are all essential aspects of our journey towards the restoration of full communion. All of this precedes and always accompanies that other essential aspect of this journey, namely, theological dialogue. An authentic dialogue is, in every case, an encounter between persons with a name, a face, a past, and not merely a meeting of ideas.

This is especially true for us Christians, because for us the truth is the person of Jesus Christ. The example of Saint Andrew, who with another disciple accepted the invitation of the Divine Master, "Come and see", and "stayed with him that day" (Jn 1:39), shows us plainly that the Christian life is a personal experience, a transforming encounter with the One who loves us and who wants to save us. In addition, the Christian message is spread thanks to men and women who are in love with Christ, and cannot help but pass on the joy of being loved and saved. Here again, the example of the apostle Andrew is instructive. After following Jesus to his home and spending time with him, Andrew "first found his brother Simon, and said to him, ‘We have found the Messiah' (which means Christ). He brought him to Jesus" (Jn 1:40-42). It is clear, therefore, that not even dialogue among Christians can prescind from this logic of personal encounter.

It is not by chance that the path of reconciliation and peace between Catholics and Orthodox was, in some way, ushered in by an encounter, by an embrace between our venerable predecessors, Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras and Pope Paul VI, which took place fifty years ago in Jerusalem. Your Holiness and I wished to commemorate that moment when we met recently in the same city where our Lord Jesus Christ died and rose.

By happy coincidence, my visit falls a few days after the fiftieth anniversary of the promulgation of Unitatis Redintegratio, the Second Vatican Council's Decree on Christian Unity. This is a fundamental document which opened new avenues for encounter between Catholics and their brothers and sisters of other Churches and ecclesial communities.

In particular, in that Decree the Catholic Church acknowledges that the Orthodox Churches "possess true sacraments, above all – by apostolic succession – the priesthood and the Eucharist, whereby they are still joined to us in closest intimacy" (15). The Decree goes on to state that in order to guard faithfully the fullness of the Christian tradition and to bring to fulfilment the reconciliation of Eastern and Western Christians, it is of the greatest importance to preserve and support the rich patrimony of the Eastern Churches. This regards not only their liturgical and spiritual traditions, but also their canonical disciplines, sanctioned as they are by the Fathers and by Councils, which regulate the lives of these Churches (cf. 15-16).

I believe that it is important to reaffirm respect for this principle as an essential condition, accepted by both, for the restoration of full communion, which does not signify the submission of one to the other, or assimilation. Rather, it means welcoming all the gifts that God has given to each, thus demonstrating to the entire world the great mystery of salvation accomplished by Christ the Lord through the Holy Spirit. I want to assure each one of you here that, to reach the desired goal of full unity, the Catholic Church does not intend to impose any conditions except that of the shared profession of faith. Further, I would add that we are ready to seek together, in light of Scriptural teaching and the experience of the first millennium, the ways in which we can guarantee the needed unity of the Church in the present circumstances. The one thing that the Catholic Church desires, and that I seek as Bishop of Rome, "the Church which presides in charity", is communion with the Orthodox Churches. Such communion will always be the fruit of that love which "has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us" (cf. Rom 5:5), a fraternal love which expresses the spiritual and transcendent bond which unites us as disciples of the Lord.

In today's world, voices are being raised which we cannot ignore and which implore our Churches to live deeply our identity as disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ.

The first of these voices is that of the poor. In the world, there are too many women and men who suffer from severe malnutrition, growing unemployment, the rising numbers of unemployed youth, and from increasing social exclusion. These can give rise to criminal activity and even the recruitment of terrorists. We cannot remain indifferent before the cries of our brothers and sisters. These ask of us not only material assistance – needed in so many circumstances – but above all, our help to defend their dignity as human persons, so that they can find the spiritual energy to become once again protagonists in their own lives. They ask us to fight, in the light of the Gospel, the structural causes of poverty: inequality, the shortage of dignified work and housing, and the denial of their rights as members of society and as workers. As Christians we are called together to eliminate that globalization of indifference which today seems to reign supreme, while building a new civilization of love and solidarity.

A second plea comes from the victims of the conflicts in so many parts of our world. We hear this resoundingly here, because some neighbouring countries are scarred by an inhumane and brutal war. Taking away the peace of a people, committing every act of violence – or consenting to such acts – especially when directed against the weakest and defenceless, is a profoundly grave sin against God, since it means showing contempt for the image of God which is in man. The cry of the victims of conflict urges us to move with haste along the path of reconciliation and communion between Catholics and Orthodox. Indeed, how can we credibly proclaim the message of peace which comes from Christ, if there continues to be rivalry and disagreement between us (cf. Paul VI, Evangelii Nuntiandi, 77)?

A third cry which challenges us is that of young people. Today, tragically, there are many young men and women who live without hope, overcome by mistrust and resignation. Many of the young, influenced by the prevailing culture, seek happiness solely in possessing material things and in satisfying their fleeting emotions. New generations will never be able to acquire true wisdom and keep hope alive unless we are able to esteem and transmit the true humanism which comes from the Gospel and from the Church's age-old experience. It is precisely the young who today implore us to make progress towards full communion. I think for example of the many Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant youth who come together at meetings organized by the Taizé community. They do this not because they ignore the differences which still separate us, but because they are able to see beyond them; they are able to embrace what is essential and what already unites us.

Your Holiness, we are already on the way towards full communion and already we can experience eloquent signs of an authentic, albeit incomplete union. This offers us reassurance and encourages us to continue on this journey. We are certain that along this journey we are helped by the intercession of the Apostle Andrew and his brother Peter, held by tradition to be the founders of the Churches of Constantinople and of Rome. We ask God for the great gift of full unity, and the ability to accept it in our lives. Let us never forget to pray for one another.

WHAT IS THE LITURGY?

Address of His Holiness Pope Francis at the Divine Liturgy of the Patriarchal Cathedral of St. George (30.11.14)

When I was the Archbishop of Buenos Aires, I often took part in the celebration of the Divine Liturgy of the Orthodox communities there. Today, the Lord has given me the singular grace to be present in this Patriarchal Church of Saint George for the celebration of the Feast of the holy Apostle Andrew, the first-called, the brother of Saint Peter, and the Patron Saint of the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

Meeting each other, seeing each other face to face, exchanging the embrace of peace, and praying for each other, are all essential aspects of our journey towards the restoration of full communion. All of this precedes and always accompanies that other essential aspect of this journey, namely, theological dialogue. An authentic dialogue is, in every case, an encounter between persons with a name, a face, a past, and not merely a meeting of ideas.

This is especially true for us Christians, because for us the truth is the person of Jesus Christ. The example of Saint Andrew, who with another disciple accepted the invitation of the Divine Master, "Come and see", and "stayed with him that day" (Jn 1:39), shows us plainly that the Christian life is a personal experience, a transforming encounter with the One who loves us and who wants to save us. In addition, the Christian message is spread thanks to men and women who are in love with Christ, and cannot help but pass on the joy of being loved and saved. Here again, the example of the apostle Andrew is instructive. After following Jesus to his home and spending time with him, Andrew "first found his brother Simon, and said to him, ‘We have found the Messiah' (which means Christ). He brought him to Jesus" (Jn 1:40-42). It is clear, therefore, that not even dialogue among Christians can prescind from this logic of personal encounter.

It is not by chance that the path of reconciliation and peace between Catholics and Orthodox was, in some way, ushered in by an encounter, by an embrace between our venerable predecessors, Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras and Pope Paul VI, which took place fifty years ago in Jerusalem. Your Holiness and I wished to commemorate that moment when we met recently in the same city where our Lord Jesus Christ died and rose.

By happy coincidence, my visit falls a few days after the fiftieth anniversary of the promulgation of Unitatis Redintegratio, the Second Vatican Council's Decree on Christian Unity. This is a fundamental document which opened new avenues for encounter between Catholics and their brothers and sisters of other Churches and ecclesial communities.

In particular, in that Decree the Catholic Church acknowledges that the Orthodox Churches "possess true sacraments, above all – by apostolic succession – the priesthood and the Eucharist, whereby they are still joined to us in closest intimacy" (15). The Decree goes on to state that in order to guard faithfully the fullness of the Christian tradition and to bring to fulfilment the reconciliation of Eastern and Western Christians, it is of the greatest importance to preserve and support the rich patrimony of the Eastern Churches. This regards not only their liturgical and spiritual traditions, but also their canonical disciplines, sanctioned as they are by the Fathers and by Councils, which regulate the lives of these Churches (cf. 15-16).

I believe that it is important to reaffirm respect for this principle as an essential condition, accepted by both, for the restoration of full communion, which does not signify the submission of one to the other, or assimilation. Rather, it means welcoming all the gifts that God has given to each, thus demonstrating to the entire world the great mystery of salvation accomplished by Christ the Lord through the Holy Spirit. I want to assure each one of you here that, to reach the desired goal of full unity, the Catholic Church does not intend to impose any conditions except that of the shared profession of faith. Further, I would add that we are ready to seek together, in light of Scriptural teaching and the experience of the first millennium, the ways in which we can guarantee the needed unity of the Church in the present circumstances. The one thing that the Catholic Church desires, and that I seek as Bishop of Rome, "the Church which presides in charity", is communion with the Orthodox Churches. Such communion will always be the fruit of that love which "has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us" (cf. Rom 5:5), a fraternal love which expresses the spiritual and transcendent bond which unites us as disciples of the Lord.

In today's world, voices are being raised which we cannot ignore and which implore our Churches to live deeply our identity as disciples of the Lord Jesus Christ.

The first of these voices is that of the poor. In the world, there are too many women and men who suffer from severe malnutrition, growing unemployment, the rising numbers of unemployed youth, and from increasing social exclusion. These can give rise to criminal activity and even the recruitment of terrorists. We cannot remain indifferent before the cries of our brothers and sisters. These ask of us not only material assistance – needed in so many circumstances – but above all, our help to defend their dignity as human persons, so that they can find the spiritual energy to become once again protagonists in their own lives. They ask us to fight, in the light of the Gospel, the structural causes of poverty: inequality, the shortage of dignified work and housing, and the denial of their rights as members of society and as workers. As Christians we are called together to eliminate that globalization of indifference which today seems to reign supreme, while building a new civilization of love and solidarity.

A second plea comes from the victims of the conflicts in so many parts of our world. We hear this resoundingly here, because some neighbouring countries are scarred by an inhumane and brutal war. Taking away the peace of a people, committing every act of violence – or consenting to such acts – especially when directed against the weakest and defenceless, is a profoundly grave sin against God, since it means showing contempt for the image of God which is in man. The cry of the victims of conflict urges us to move with haste along the path of reconciliation and communion between Catholics and Orthodox. Indeed, how can we credibly proclaim the message of peace which comes from Christ, if there continues to be rivalry and disagreement between us (cf. Paul VI, Evangelii Nuntiandi, 77)?

A third cry which challenges us is that of young people. Today, tragically, there are many young men and women who live without hope, overcome by mistrust and resignation. Many of the young, influenced by the prevailing culture, seek happiness solely in possessing material things and in satisfying their fleeting emotions. New generations will never be able to acquire true wisdom and keep hope alive unless we are able to esteem and transmit the true humanism which comes from the Gospel and from the Church's age-old experience. It is precisely the young who today implore us to make progress towards full communion. I think for example of the many Orthodox, Catholic and Protestant youth who come together at meetings organized by the Taizé community. They do this not because they ignore the differences which still separate us, but because they are able to see beyond them; they are able to embrace what is essential and what already unites us.

Your Holiness, we are already on the way towards full communion and already we can experience eloquent signs of an authentic, albeit incomplete union. This offers us reassurance and encourages us to continue on this journey. We are certain that along this journey we are helped by the intercession of the Apostle Andrew and his brother Peter, held by tradition to be the founders of the Churches of Constantinople and of Rome. We ask God for the great gift of full unity, and the ability to accept it in our lives. Let us never forget to pray for one another.

WHAT IS THE LITURGY?

THE LITURGY AS HEAVEN ON EARTH

click on: THE INNER MEANING OF THE LITURGY - I

No comments:

Post a Comment