Half way between the Thursday of the Ascension in the (Latin) Gregorian Calendar and the Ascension Thursday of the (Orthodox) Julian Calendar, lies the Sunday of the Ascension as celebrated nowadays in much of the Latin Rite. We shall, therefore, celebrate both.

JEAN CORBON O.P. ON THE ASCENSION

Chapter 4

The Ascension and the Eternal Liturgy

''The river of life, rising from the throne of God and of the Lamb" (Rev 22:1), flowed hidden in the passage of the time of the promises and God's patience. But "when the completion of the time came" (Gal 4:4), that is, when the incarnation occurred, the river entered into our world and assumed our flesh. In the "hour" of the cross and the resurrection it sprang forth from the incorruptible and life-giving body of Christ. From that moment on it has been and is liturgy. A new period thus began within "the present time" (1) in which after its decisive defeat death carries on its war on all fronts but in which, at the same time, the Passage of the Lord continues to penetrate the depths of humanity and history. We are in "the last times." (2)

Just as the hour of Jesus has his cross and his resurrection as inseparable phases, so too the "moment" or "date" (kairos) (3) which begins the "last times" has the Lord's ascension and the outpouring of his Spirit as inseparable phases. The relation between the "hour" and this special date or moment is to be looked for not in their chronological succession (to look for it there would be to remain at the level of dead time [4]) but in the exercise of the divino-human energy whereby the river of life becomes liturgy.

Jesus died and rose "once and for all," and that event now lives on through all of history and sustains it. But when in his humanity he takes his place beside the Father and from there pours out the life-giving gift of the Spirit, he does not cease to manifest and carry out the liturgy. There is but a single Passover or Passage but its mighty energy is displayed in a continual ascension and Pentecost.

It is highly regrettable that the majority of the faithful pay so little heed to the ascension of the Lord. Their lack of appreciation of it is closely connected with their lack of appreciation of the mystery of the liturgy. A superficial reading of the end of the Synoptic Gospels and the first chapter of Acts can give the impression that Christ simply departed. In the mind of readers not submissive to the Spirit a page has been turned; they now begin to think of Jesus as in the past and to speak of what "he said" and what "he did."

They have carefully sealed up the tomb again and filled up the fountain with sand; they continue to "look among the dead for someone who is alive" and they return to their narrow lives in which some things have to do with morality and others with cult, as in the case of the upright men and women of the old covenant. But in fact the ascension is a decisive turning point. It does indeed mark the end of something that is not simply to be cast aside: the end of a relationship to Jesus that is still wholly external. Above all, however, it marks the beginning of an entirely new relationship of faith and of a new time: the liturgy of the last times.

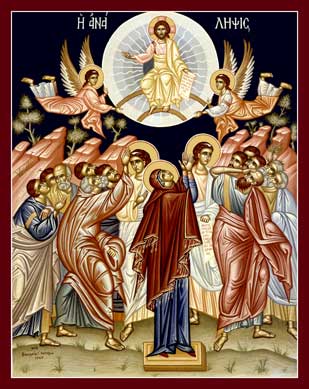

We can only wonder at, and try to recapture for ourselves, the insight shown by the early Christians and by Christians down to the beginning of the second millennium, who placed the Christ of the ascension in the dome of their churches. When the faithful gathered to manifest and become the body of Christ, they saw their Lord both as present and as coming. He is the head and draws his body toward the Father while giving it life through his Spirit.

The iconography of the churches of both East and West during that period was as it were an extension of the mystery, of the ascension throughout the entire visible church. Christ, the Lord of all" (Pantocrator), is "the cornerstone which the builders had rejected"; (5) when he is raised up on the cross, he is in fact being raised to the Father's side and, in his life-giving humanity, becomes with the Father the wellspring of the river of life. (6)

In the vault of the apse there was also to be seen the Woman and her Child (Rev 12); that single vision embraces both the Virgin who gives birth and the Church in the wilderness. In the sanctuary were to be seen the angels of the ascension or other expressions of the theophanies of the Holy Spirit. (7) Finally, on the walls of the church were the living stones: the throng of saints, the "cloud of witnesses," the Church of the "firstborn" (Heb 12:23).

The ascension of the Lord was thus really the new space for the liturgy of the last times, and the iconography of the church built of stone was its transparent symbol. (8) In his ascension, then, Christ did not at all disappear; on the contrary, he began to appear and to come. For this reason, the hymns we use in our churches sing of him as "the Sun of justice" that rises in the East. He who is the splendor of the Father and who once descended into the depths of our darkness is now exalted and fills all things with his light.

Our last times are located between that first ascension and the ascension that will carry him to the zenith of his glorious parousia. The Lord has not gone away to rest from his redemptive toil; his "work" (Jn 5:17) continues, but now at the Father's side, and because he is there he is now much closer to us, "very near to us," (9) in the work that is the liturgy of the last times. "He leads captives," namely, us, to the new world of his resurrection, and bestows his "gifts," his Spirit, on human beings (see Eph 4:7-10). His ascension is a progressive movement, "from beginning to beginning." (10)

Jesus is, of course, at his Father's side. If, however, we reduce this "ascent" to a particular moment in our mortal history, we simply forget that beginning with the hour of his cross and resurrection Jesus and the human race are henceforth one. He became a son of man in order that we might become children of God. The ascension is progressive "until we all ... form the perfect Man fully mature with the fullness of Christ himself" (Eph 4:13).

The movement of the ascension will be complete only when all the members of his body have been drawn to the Father and brought to life by his Spirit. Is that not the meaning of the answer the angels gave to the disciples: "Why are you Galileans standing here looking into the sky? This Jesus who has been taken up from you into heaven will come back in the same way as you have seen him go to heaven" (Acts 1:11). The ascension does not show us in advance the setting of the final parousia; it is rather the activation of the paschal energy of Christ who "fills all things" (Eph 4: 1 0). It is the ever-new "moment" of his coming.

The Heavenly Liturgy

What, then, is this "work" by which the conqueror of death pours out his life in abundance? What is this energy with which the Father and the risen Son henceforth "still go on working" (Jn 5:17)? It is the fontal liturgy in which the life-giving humanity of the incarnate Word joins with the Father to send forth the river of life; it is the heavenly liturgy. (11) In the words of the Letter to the Hebrews, "the principal point of all that we have said is that we have a high priest [who... has taken his seat at the right of the throne of divine Majesty in heaven, and is the minister of the divine sanctuary and of the true Tent which the Lord, and not any man, set up" (Heb 8:1-2). (12) This liturgy is eternal (inasmuch as the body of Christ remains incorruptible) and will not pass away; on the contrary, it is this liturgy that "causes" the present world "to pass" into the glory of the Father in an ever more efficacious great Pasch.

This mystery could not be revealed until its consummation was at hand. That is the meaning conveyed by the final book of the Bible, the Apocalypse or "revelation" of the complete mystery of Christ. To us who are living in the last times this book makes known the hidden face of history. There are many hypotheses to explain the book in its final form, but none denies the noteworthy fact that the vision of faith expressed in the book develops consistently on two levels.

It seems at first glance that, as with icons, we have a lower level (earth) and a higher level (heaven). But we must not let ourselves be misled by the literary device. In the increasingly dramatic movement of the last times these two levels are co-inherent. The one that is more obvious unveils the carnival of death being celebrated by the prince of this world; the one that is more hidden takes us into the presence of him who holds the keys of death. The experience in both cases is an experience of the liturgy.

As the very name makes clear, (13) the liturgy essentially involves action and energy; the heavenly liturgy tells us of all the actors in the drama: Christ and the Father, the Holy Spirit, the angels and all living things, the people of God (whether already enjoying incorruptible life or still living through the great tribulation), the prince of this world, and the powers which worship him. The heavenly liturgy is "apocalyptic" in the original sense of this word: it " reveals" everything in the very moment in which it brings it to pass. When the event is present, prophecy becomes "apocalyptic."

The Return to the Father

"I saw a throne standing in heaven, and the One who was sitting on the throne" (Rev 4:2). At the heart of the liturgy, at its very source, there is the Father! He is obviously the fountain both in eternity and since the beginning of time: "the fountain of life, the fountain of immortality, the fountain of all grace and all truth", (14) the fountain that the patriarchs were looking for when they dug wells, the one that the people abandoned for cracked water-tanks, the one that drew the Samaritan woman, the one for which the dying Jesus thirsted. But at this point there was no liturgy as yet.

Only "when the life that burst from the tomb had become liturgy could the liturgy finally be celebrated -- only when the river returned to its fountainhead, the Father. The liturgy begins in this movement of return. The energy of the gift in which the Father committed himself unreservedly from the beginning; the suffering love with which he handed over his Son and his Spirit; the kenoses (emptying) that had marked the river of life since creation; the promise; the incarnation that included even death on a cross and burial in a tomb: all this faithful and patient "tradition" of the Father's agape at last bursts forth in its fruit. The liturgy is this vast reflux of love in which everything turns into life. That love had always cast its seed in pure unmerited generosity; now is the everlasting time for giving thanks. "For his love is everlasting!"

"If you only knew what God is offering!" If we only knew how to enter, without any merit on our part, through the "door open in heaven" (Rev 4:1) into the joy of the Father! For the liturgy is the celebration of the Father's joy. He whom we used to fear as Adam did when he hid far from his face (Gen 3:8); of whom we had a mistaken idea, like the two sons in the parable (Lk 15:11-31); or whose ineffable name -- "I AM" (Ex 3:14) -- we used to murmur amid the cloud -- now at last we can recognize him: "He is, he was, and he is to come" (Rev 1:4), and "worship him in spirit and truth: that is the kind of worshiper the Father seeks" (Jn 4:23). The joy we give to the Father by letting him find us inspires the exultation that keeps the liturgy ever alive. How could he, the wellspring, not be filled with wonder when he sees human beings becoming a wellspring in their turn and responding to his eternal thirst?

Transcending the parables in which Jesus gave a glimpse of this jubilation ("There will be more rejoicing in heaven over one sinner repenting" Lk 15:7) is the reality now attained: the eternal joy of the Father at the return of his beloved Son. The latter had gone forth as the only Son; now he returns in the flesh, bringing the Father's adoptive children: "Look, I and the children whom God has given me" (Heb 2:13). The Father's indescribable joy has taken concrete form and embodiment in the countless faces that mirror the face of his beloved Son. In them the joy of the wellspring can break out and leap up and sing like so many echoes and accents made possible by pure grace, and each of them is unique: "In the same way, I tell you, there is rejoicing among the angels of God" (Lk 15:10).

"God's glory is the living human being." (15) The glorification of the Father began in the hour in which the Son of man was glorified (Jn 12:28). From that point on it continues without intermission. (16) The reason is not only that he has "brought everything together" in Christ "to the praise of the glory of his grace" (Eph 1:3-14), but also that, to his joy, new adopted children are born at each moment as they emerge from the great tribulation.

The liturgical language of the Church has from the beginning expressed this glorification in a term that we are rediscovering today: "doxology." The liturgy is essentially doxological" in its celebration of the wellspring. (17) The astounding thing is that he from whom the energy of the Gift proceeds eternally should now reveal himself as also an energy of acceptance: from all creatures who are conformed to his Son he accepts the jubilant reflux of the river of life. The celebration of the eternal liturgy consists in this ever new ebb and flow of the trinitarian communion as shared by all of creation: the angels before his face, the living creatures, all the "times" (Rev 4: 4-11).

"Ebb and flow": because the Father does not keep this joy for himself when he receives it but causes it to flow forth anew in still greater love and life. The eternal liturgy is thus the celebration of the sharing in which each is wholly for the others. The mystery of holiness has at last turned into liturgy because it is shared and communicated. In its source and in its unfolding the celebration is entirely bathed in this radiant holiness: "holy, holy holy...... It takes the form of adoration.

The Lord of History

Once we have realized that the ascension of Jesus is the reflux of the river of life to its fountainhead, the return of the Word to the heart of the Father after having accomplished its mission (Is 55:11), we will see how the various biblical images converge, especially those of the Apocalypse, which speaks of the heavenly liturgy in its present operation. The heavenly liturgy celebrates the ongoing event of the return of the Son -- and of all others in him -- to the Father's house. It is the feast, the banquet, even the marriage, of the beloved and his bride. All is not yet completed, but the great event of history is now present at the heart of the Trinity; there, one with the Father, it becomes a wellspring.

This covenant at the wellspring is expressed in the central symbol of the Book of Revelation: the Lamb. "Then I saw, [standing] in the middle of the throne with its four living creatures and the circle of the elders, a Lamb that seemed to have been sacrificed" (Rev 5:6). Christ is risen ("standing") but he carries the signs of his passage through our death ("sacrificed"). His key action in the heavenly liturgy is to take the scroll from the right hand of him who sits on the throne; no one except the Lamb is able to break the seals and open the scroll (Rev 5).

Only Jesus, by his victory over death, has accomplished the event that writes history and deciphers its meaning. Apart from his Pasch-Passage everything is meaningless. Human beings can write history, while other human beings think of themselves as making it. But only he who brings time to -- its completion can reveal the "meaning of history" by rending the veil of death and deceit. He is the meaning of our history because he is the event that makes it. He is the Lord of history.

All this means that the liturgy of Christ's ascension is the harvest feast not only of the history before the ascension but also of ongoing history: the paschal event is constantly bearing its eternal fruit in the history that we experience. For the Lord of history is still the "trustworthy" and "true" knight who "in uprightness ... makes war," whose "cloak [is] soaked in blood, and whose name is "the Word of God" (Rev 19:11-21). His liturgy is the concrete extension of his victory in the struggle of the last times: "Do not be afraid; it is I, the First and the Last; I am the Living One, I was dead and look -- I am alive for ever and ever, and I hold the keys of death and of Hades" (Rev 1: 17-18).

The heavenly liturgy is the gestation of the new creation because our history is sustained by Christ who is now in the bosom of the Blessed Trinity. It is there that the Lord of history is at every moment the Savior of his body and of the least of his brothers and sisters: he calls and feeds them, heals them and makes them grow, forgives and transforms them, delivers and divinizes them, tells them that they are loved by the Father and are being increasingly united to him until they reach their full stature in the kingdom.

The energy which Christ exerts in the heavenly liturgy is summed up by the Letter to the Hebrews in a title which the Letter intends should convey the whole newness of the paschal event: Jesus is our high priest. "'Look, I and the children whom God has given me.' Since all the children share in the same human nature, he too shared equally in it, so that by his death he could set aside him who held the power of death, namely the devil.... It was essential that he should in this way be in made completely like his brothers so that he could become a compassionate and trustworthy high priest for their relationship to God" (Heb 2:13-17). "He became for all who obey him the source of eternal salvation" (Heb 5:9). "His power to save those who of the heavenly liturgy is to be heard a groaning cry, that of the witnesses "killed on account of the Word of God"; from underneath the altar they shout in a loud voice: "Holy, true Master, how much longer will you wait before you pass sentence?" (Rev 6:9-10).

History did not come to an end with the ascension; on the contrary it is en route to its final deliverance; the "last times" have begun. Each time that the Lamb breaks a seal on the scroll of history, the same cry echoes -- "Come!" What, then, is this roaring of mighty waters in creation that is undergoing the pangs of childbirth, and in the human body, and even in the depths of the human heart (Rom 8:22-27)? The ebb and flow of the heavenly liturgy ceaselessly draws the world b come to God through him is absolute, since he lives for ever to intercede for them" (Heb 7:25). "As the high priest of all the blessings which were to come ... he has entered the sanctuary once and for all, taking with him ... his own blood, having won an eternal redemption" (Heb 9:12). "This he did once and for all by offering himself" (Heb 7:27).

In the iconography of the ascension the Lord Jesus holds the scroll of history but he also blesses it with his right hand. Being one with the Father, the Lamb is a source of blessing: he pours out the river of life. Because we are "already" in the eternal liturgy, its current carries us along all the more impatiently to its consummation. For at the heart of the heavenly liturgy is to be heard a groaning cry, that of the witnesses "killed on account of the Word of God"; from underneath the altar they shout in a loud voice: "Holy, true Master, how much longer will you wait before you pass sentence?" (Rev 6:9-10).

History did not come to an end with the ascension; on the contrary it is en route to its final deliverance; the "last times" have begun. Each time that the Lamb breaks a seal on the scroll of history, the same cry echoes -- "Come!" What, then, is this roaring of mighty waters in creation that is undergoing the pangs of childbirth, and in the human body, and even in the depths of the human heart (Rom 8:22-27)? The ebb and flow of the heavenly liturgy ceaselessly draws the world back to its wellspring, and it is then that the river of life gushes forth in its final kenosis: the Holy Spirit.

please click on:

by A. Schmemann (Orthodox)

(plus) some lectures by Metropolitan Kallistos Ware

by Fr Thomas Hopko

Orthodox

by Fr Thomas Hopko

More will be added during the day.

ABBOT PAUL'S HOMILY

ABBOT PAUL'S HOMILY

Since Easter Sunday we have been celebrating the Resurrection of Jesus our Lord, reading the wonderful Gospel narratives, singing those glorious Easter hymns and meditating on the tremendous mysteries of our faith. So many images of our Risen Lord come to mind when we think of the Resurrection: the empty Tomb, the women and the angels, Mary Magdalene, who took him for the gardener, Cleopas and his companion, who failed to recognise Jesus on the road to Emmaus until he entered into their home and broke bread for them, the disciples in the upper room and the meeting with Thomas a week later (Blessed are those who have not seen and yet believe), the encounter on the shores of the Lake Galilee (Do you love me more than these?) and, then, reading the rest of the Gospel in the light of the Resurrection and beginning to see what it all means. What a forty days it has been!

The final event is that recounted in today’s Gospel from St Mark. “’Go out to the whole world; proclaim the Good News to all creation.’ So the Lord Jesus, after he had spoken to them, was taken up into heaven: there at the right hand of God he took his place, while, they, going out, preached everywhere, the Lord working with them and confirming the word by the signs that accompanied it.” Today we celebrate Jesus being taken up into heaven, his Ascension, but what is it he takes up into heaven? He takes with him his body, born of Mary his Mother, a body just like ours. However, his body was scourged and crowned with thorns, crucified, died and was buried and lay three days in the sepulchre; his body rose victoriously on the third day and appeared to the disciples, showing them his hands and his side, a body whose wounds were still open when he invited Thomas to put his finger into the holes in his hands and his hand into the wound in his side. The body that Jesus takes up into heaven is risen, glorified auch is the depth of his mercy and love.

Pope Francis often has interesting insights into Scripture and the Christian faith. He said on Ascension Day last year that, “When Jesus returns to the Father, he shows him his wounds and says to him, ‘Look, Father, this is the price of the forgiveness that you give.’ When the Father looks at his Son’s wounds, he always forgives us, not because we are good but because Jesus paid the price for us. Looking at Jesus’ wounds, the Father manifests the fullness of his mercy. This is the great work of Jesus in heaven today: showing the Father the price of forgiveness, his wounds. How wonderful this is because it moves us not to have fear of asking forgiveness. The Father always forgives because he looks at the wounds of Jesus, looks at our sin and forgives it.”

Today’s Gospel also reminds us that, just as Jesus sent out his apostles to preach the Good News and to share with the whole of creation the joy of God’s loving mercy, so he is sending us out as missionaries today. There is nothing optional about the command of Jesus, “Go out to the whole world: proclaim the good news.” We cannot call ourselves Christian if we keep the Good News to ourselves. If we truly live in the presence of the Lord and the power of his Spirit, then we too can be the apostles Jesus wants us to be. That’s what’s so exciting about being a Christian, the fact that we take Jesus to others.

So we ask Him today to transform our lives through his Resurrection and Ascension and we thank him for the gift of forgiveness and for calling each one of us to be an apostle and so share in the mission of the Church. Will you take up the challenge?nd transformed into a new reality and yet the wounds of his Passion and Death, by which he redeemed us and reconciled us with the Father, are still open and will remain so until the last soul is saved.

No comments:

Post a Comment