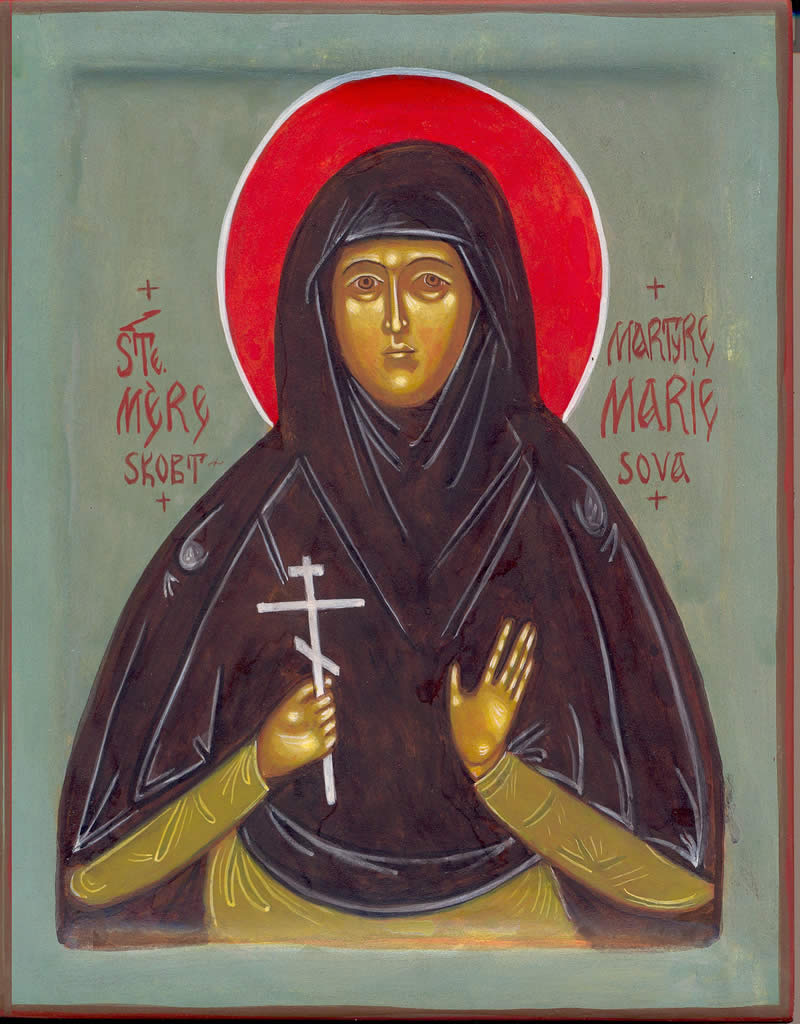

MOTHER MARIA SKOBTSOVA

Mother Maria Skobtsova — now recognized as Saint Maria of Paris — died at Ravensbrück concentration camp in 1945, paying with her life for her vocation of hospitality. In many ways, it was a life that similar to that of Dorothy Day. The extraordinary courage Mother Maria displayed in confronting Nazism is becoming better known, thanks to her recent canonization, but English translations of her essays have been difficult to obtain. Now Mother Maria Skobtsova: Essential Writings is available as part of the Orbis Modern Spiritual Masters Series.

Mother Maria Skobtsova — now recognized as Saint Maria of Paris — died at Ravensbrück concentration camp in 1945, paying with her life for her vocation of hospitality. In many ways, it was a life that similar to that of Dorothy Day. The extraordinary courage Mother Maria displayed in confronting Nazism is becoming better known, thanks to her recent canonization, but English translations of her essays have been difficult to obtain. Now Mother Maria Skobtsova: Essential Writings is available as part of the Orbis Modern Spiritual Masters Series.

Here is one review:

When, during Great Lent of 1932, Metropolitan Evlogii received the monastic vows of Elisaveta Skobtsova at the church of St. Serge Institute in Paris, many must have been scandalized. After all, this woman had been twice divorced, had an illegitimate child by another man, had leftist political sympathies and was an original by any standard. At her profession she took the name of Maria in memory of St. Mary of Egypt, a prostitute who became a hermit and extreme ascetic. As a religious, Mother Maria continued to scandalize. Her “angelic habit” was usually stained with grease from the kitchen and paint from her workshop; she would hang out at bars late at night; she had little patience with the long Orthodox liturgies, and found the strict and frequent fasts a burden. And — horror of horrors — she even smoked in public in her habit! Her canonization process has been initiated by the Orthodox church. Her “essential writings” constitute the latest book in the Orbis series of Modern Spiritual Masters.

Jim Forest introduces this volume with a biographical essay of Mother Maria. The book consists mainly of articles published in obscure magazines and one long text discovered only recently. This is not stuff for the faint-hearted. The charity that Mother Maria proposes as an obligation of Christian life is severe, absolute, uncompromising and insane. We must love others as Jesus loved, without reserve, in an utter and unconditional self-sacrificing of everything. We must follow the Son of Man not only to Golgotha but beyond — to the very depths of hell where God is absent. We must be willing, as was St. Paul, to be separated from Christ so long as we can see our brothers saved. For we are not alone before God. As members of the body of Christ, each of us shares the fate of all; each of us is justified by the righteous and bears responsibility for the sins of sinners. This means taking upon oneself the crosses of all: their doubts, griefs, temptations, falls and sins.

And Mother Maria leaves us no wiggle room: “It goes without saying that it seems to every man as if nothing will be left of his heart, that it will bleed itself dry if he opens it, not for the countless swords of all of humanity, but even for the one sword of the nearest and dearest of his brothers. … Natural law, which in some false way has penetrated into the spiritual life, will say definitively: Bear your cross responsibly, freely, and honestly, opening your heart now and then to the cross-swords of your neighbor and that is all. … But if the cross of Christ is scandal and folly for natural law, the two- edged weapon that pierces the soul should be as much of a folly and scandal for it. … All that is not the fullness of cross-bearing is sin.” This is, of course, sheer madness — the madness of the Eternal Wisdom, judged and condemned, spat upon and mocked, abused and humiliated, making his the sins of all and descending to the place of the damned.

Mother Maria has no patience with those who are preoccupied with their “spiritual life” and their personal relationship with God. It is precisely this spiritual life that must be lost, given in sacrifice, if one truly loves. If this is not given, tongues and prophecy are useless, faith and martyrdom are in vain. Christian egocentrism is a contradiction in terms. He who seeks to save his soul will lose it. There is no room for complacency or self-righteousness. These are idols that must be destroyed. There is a gift to be given and it must be a total gift — “thine own of thine own.”

What applies to individuals applies also to the church. In her final essay on “Types of Religious Life” (which really concerns types of piety), Mother Maria examines certain aspects of the church’s inner life and the danger of a fascination with its institutional structures, rituals, esthetic beauties and ascetical practices as ends in themselves to the detriment of a relationship to the Living Christ whose image is found in every person. Although she refers directly to the Orthodox church, her words are equally valid for all Christian churches:

“The eyes of love will perhaps be able to see how Christ himself departs, quietly and invisibly, from the sanctuary that is protected by a splendid iconostasis. The singing will continue to resound, the clouds of incense will arise, the faithful will be overcome by the ecstatic beauty of the services. But Christ will go out onto the church steps and mingle with the crowd: the poor, the lepers, the desperate, the embittered, the holy fools. Christ will go out into the streets, the prisons, the low haunts and dives. Again and again Christ lays down his soul for his friends … and so he will return to the churches and bring with him all those he has summoned to the wedding feast, has gathered from the highways, the poor and maimed, prostitutes and sinners … and [they] will not let him into the church because behind him will follow a crowd of people deformed by sin, by ugliness, drunkenness, depravity, and hate. Then their chant will fade away in the air, the smell of incense will disperse and Someone will say to them: ‘I was hungry and you gave me no food …’ ”

This does not imply a rejection of traditions and usages. In another essay, “In Defense of the Pharisees,” Mother Maria underlines the necessity of the collective memory of past blessings and the need for securities and points of reference. During certain historical epochs, of persecution or even in times of relative stability and in the absence of prophecy, adherence to traditions could be the predominant note in the life of the church, its anchor and guarantee. But this fidelity to the past must not become a paralyzing slavery. History is constantly presenting new challenges, and the church must be free to receive the prophetic gifts when such gifts are given and renew itself accordingly. Faced with modernity and bearing witness to the Gospel in our contemporary world, the church cannot let itself be bound by archaic and irrelevant structures.

Mother Maria’s view of the Christian life is anything but horizontal. She has no use for “trends of social Christianity … based on a certain rationalistic humanism [that] apply only the principles of Christian morality to ‘this world’ and do not seek a spiritual and mystical basis for their constructions.” The gift of oneself to others must be rooted in an intense and loving communion with the Son of God “who descended into the world, became incarnate in the world, totally, entirely, without holding any reserve, as it were, for his divinity. … Christ’s love does not know how to measure and divide, does not know how to spare itself.” Our love should not be any different.

In her writings, Mother Maria expresses what she tried to live. After taking her monastic vows — which she saw as a means of committing herself irrevocably to her vocation within the church — she rented a building that became her monastery, a soup kitchen and a refuge for the rejects of society. It resembled a Catholic Worker house more than anything else. One observer described the “monastery” as “a strange pandemonium; we have young girls, madmen, exiles, unemployed workers and, at the moment, the choir of the Russian opera and the Gregorian choir of Dom Malherbe, a missionary center, and now services in the chapel every morning and evening.” The monastery hosted lectures and discussions with speakers from the St. Serge Institute. Mother Maria’s very intense, mystical and personalist convictions did not prevent her from organizing on a larger scale. She founded a sanatorium for impoverished Russians suffering from tuberculosis and was instrumental in the launching of Orthodox Action with its multiple charitable works.

When the German armies occupied Paris, the monastery of Mother Maria became a refuge for persecuted Jews until escape routes could be found. For those who requested them, false baptismal certificates were provided. The Nazis eventually discovered what was going on. Mother Maria, her son Yuri, the monastery’s chaplain and its lay administrator were detained and sent to concentration camps. Only the lay administrator would survive. Those who knew Mother Maria in the camps bore witness to the courage, hope and optimism she imparted to others in the worst of conditions. The date and circumstances of her death are uncertain. There were reports that her name appeared on a list of those sent to the gas chambers on April 31, 1945, and that she offered herself in the place of a young Polish woman — but that has not been fully established.

Maria Skobtsova is, indeed, in the tradition of those fools for Christ who call the church to its essential mission, who strip aside illusions and delusions, a sign of contradiction to all that is human prudence and human “decency.” She challenges us in our complacency and self-satisfaction, our half-measures and sterile piety. She brings a sledgehammer to the all-too-prevalent contemporary search for personal fulfillment, harmony, peace and satisfaction in religion. But she would not be Orthodox if death and suffering were to have the final word — for it is precisely by descending into hell, losing himself among the godless, that life vanquished the dominion of death; where life has entered, death can no longer exist. It is from the tomb that the glory of the resurrection shines forth.

Olivier Clement did the preface to this book. His final paragraph is worth citing: “If we love and venerate Mother Maria it is not in spite of her disorder, her strange views and her passion. It is precisely these qualities that make her so extraordinarily alive among so many bland and pious saints. Unattractive and dirty, strong, thick and sturdy, yes, she was truly alive in her suffering, her compassion, her passion.”

— Jerry Ryan (National Catholic Reporter)

The book can be ordered from the publisher: http://www.maryknollsocietymall.org/description.cfm?ISBN=978-1-57075-436-4

THE MEASURELESSNESS OF CHRISTIAN LOVE

by Mother Mary Skobtsova

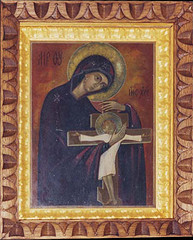

The cross-bearing Theotokos

by Mother Mary Skobtsova

Saint Mary of Paris

my source: Streams of the River

The Eucharist . . . is the Gospel in action. It is the eternally existing and eternally accomplished sacrifice of Christ and of Christ-like human beings for the sins of the world. Through it earthly flesh is deified and having been deified enters into communion again with earthly flesh. In this sense the Eucharist is true communion with the divine. And is it not strange that in it the path to communion with the divine is so closely bound up with our communion with each other. It assumes consent to the exclamation: “Let us love one another, that with one mind we may confess Father, Son and Holy Spirit: the Trinity, one in essence and undivided.”

The Eucharist needs the flesh of this world as the “matter” of the mystery. It reveals to us Christ’s sacrifice as a sacrifice on behalf of mankind, that is, as his union with mankind. It makes us into “christs,” repeating again and again the great mystery of God meeting man, again and again making God incarnate in human flesh. And all this is accomplished in the name of sacrificial love for mankind.

But if at the center of the Church’s life there is this sacrificial, self-giving eucharistic love, then where are the Church’s boundaries, where is the periphery of this center? Here it is possible to speak of the whole of Christianity as an eternal offering of the Divine Liturgy beyond church walls. What does this mean? It means that we must offer the bloodless sacrifice, the sacrifice of self-surrendering love not only in a specific place, upon the altar of a particular temple; the whole world becomes the single altar of a single temple, and for this universal Liturgy we must offer our hearts, like bread and wine, in order that they may be transubstantiated into Christ’s love, that he may be born in them, that they may become “Godmanhood” hearts, and that he may give these hearts of ours as food for the world, that he may bring the whole world into communion with these hearts of ours that have been offered up, so that in this way we may be one with him, not so that we should live anew but so that Christ should live in us, becoming incarnate in our flesh, offering our flesh upon the Cross of Golgotha, resurrecting our flesh, offering it as a sacrifice of love for the sins of the world, receiving it from us as a sacrifice of love to himself. Then truly in all ways Christ will be in all.

Here we see the measurelessness of Christian love. Here is the only path toward becoming Christ, the only path which the Gospel reveals to us. What does all this mean in a worldly, concrete sense? How can this be manifested in each human encounter, so that each encounter may be a real and genuine communion with God through communion with man? It implies that each time one must give up one’s soul to Christ in order that he may offer it as a sacrifice for the salvation of that particular individual. It means uniting oneself with that person in the sacrifice of Christ, in flesh of Christ. This is the only injunction we have received through Christ’s preaching of the Gospel, corroborated each day in the celebration of the Eucharist. Such is the only true path a Christian can follow. In the light of this path all others grow dim and hazy. One must not, however, judge those who follow other conventional, non-sacrificial paths, paths which do not require that one offer up oneself, paths which do not reveal the whole mystery of love. Nor, on the other hand, is it permitted to be silent about them. Perhaps in the past it was possible, but not today.

Such terrible times are coming. The world is so exhausted from its scabs and its sores. It so cries out to Christianity in the secret depths of its soul. But at the same time it is so far removed from Christianity that Christianity cannot, should not even dare to show a distorted, diminished, darkened image of itself. Christianity should singe the world with the fire of Christian love. Christianity should ascend the Cross on behalf of the world. It should incarnate Christ himself in the world. Even if this Cross, eternally raised again and again on high, be foolishness for our new Greeks and a stumbling block for our new Jews, for us it will still be “the power of God and the wisdom of God” (1 Cor. 1:24).

We who are called to be poor in spirit, to be fools for Christ, who are called to persecution and abuse — we know that this is the only calling given to us by the persecuted, abused, disdained and humiliated Christ. And we not only believe in the Promised Land and the blessedness to come: now, at this very moment, in the midst of this cheerless and despairing world, we already taste this blessedness whenever, with God’s help and at God’s command, we deny ourselves, whenever we have the strength to offer our soul for our neighbors, whenever in love we do not seek our own ends.

The Asceticism of the Open Door

This is an extract from an essay, “The Second Gospel Commandment,” in Mother Maria Skobtsova: Essential Writings, published by Orbis. The book’s editor is Helene Klepinin Arjakovsky, daughter of Fr. Dmitri Klepinin, co-worker with Mother Maria, who died, as she did, in a concentration camp. The translation is by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky.

“The sign of those who have reached perfection is this: if ten times a day they are given over to be burned for the love of their neighbor, they will not be satisfied with that, as Moses, and the ardent Paul, and the other disciples showed. God gave His Son over to death on the Cross out of love for His creature. And if He had had something more precious, he would have given it to us, in order thereby to gain humankind. Imitating this, all the saints, in striving for perfection, long to be like God in perfect love for their neighbor.”

“No man dares to say of his love for his neighbor that he succeeds in it in his soul, if he abandons the part that he fulfills bodily, as well as he can, and in conformity with time and place. For only this fulfillment certifies that a man has perfect love in him. And when we are faithful and true in it as far as possible, then the soul is given power, in simple and incomparable notions, to attain to the great region of lofty and divine contemplation.”

These words from St. Isaac the Syrian, both from the Philokalia, justify not only active Christianity, but the possibility of attaining to “lofty and divine contemplation” through the love of one’s neighbor — not merely an abstract, but necessarily the most concrete, practical love. Here is the whole key to the mystery of human relations as a religious path.

For me these are truly fiery words. Unfortunately, in the area of applying these principles to life, in the area of practical and ascetic behavior toward man, we have much less material than in the area of man’s attitude toward God and toward himself. Yet the need to find some precise and correct ways, and not to wander, being guided only by one’s own sentimental moods, the need to know the limits of this area of human relations — all this is very strongly felt. In the end, since we have certain basic instructions, perhaps it will not be so difficult to apply them to various areas of human relations, at first only as a sort of schema, an approximate listing of what is involved.

Let us try to find the main landmarks for this schema in the triune makeup of the human being — body, soul, and spirit. In the area of our serving each of these main principles, ascetic demands and instructions emerge of themselves, the fulfillment of which, on the one hand, is unavoidable in order to reach the goal, and, on the other hand, is beyond one’s strength.

It seems right to me to draw a line here between one’s attitude toward oneself and one’s attitude toward others. The rule of not doing to others what you do not want done to yourself is hardly applicable in asceticism. Asceticism goes much further and sets much stricter demands on oneself than on one’s neighbors.

In the area of the relation to one’s physical world, asceticism demands two things of us: work and abstinence. Work is not only an unavoidable evil, the curse of Adam; it is also a participation in the work of divine economy; it can be transfigured and sanctified. It is also wrong to understand work only as working with one’s hands, a menial task; it calls for responsibility, inspiration, and love. It should always be work in the fields of the Lord.

Work stands at the center of modern ascetic endeavor in the area of man’s relation to his physical existence. Abstinence is as unavoidable as work. But its significance is to some degree secondary, because it is needed mainly in order to free one’s attention for more valuable things than those from which one abstains. One can introduce some unsuitable passion into abstinence — and that is wrong. A person should abstain and at the same time not notice his abstinence.

A person should have a more attentive attitude toward his brother’s flesh than his own. Christian love teaches us to give our brother not only material but spiritual gifts. We must give him our last shirt and our last crust of bread. Here personal charity is as necessary and justified as the broadest social work. In this sense there is no doubt that the Christian is called to social work. He is called to organize a better life for the workers, to provide for the old, to build hospitals, care for children, fight against exploitation, injustice, want, lawlessness.

In principle the value is completely the same, whether he does it on an individual or a social level; what matters is that his social work be based on love for his neighbor and not have any latent career or material purposes. For the rest it is always justified — from personal aid to working on a national scale, from concrete attention to an individual person to an understanding of abstract systems of the right organization of social life. The love of man demands one thing from us in this area: ascetic ministry to his material needs, attentive and responsible work, a sober and unsentimental awareness of our strength and of its true usefulness.

The ascetic rules here are simple and perhaps do not leave any particular room for mystical inspiration, often being limited merely to everyday work and responsibility. But there is great strength and great truth in them, based on the words of the Gospel about the Last Judgment, when Christ says to those who stand on His right hand that they visited Him in prison, and in the hospital, fed Him when He was hungry, clothed Him when He was naked. He will say this to those who did it either on an individual or on a social level.

Thus, in the dull, laborious, often humdrum ascetic rules concerning our attitude toward the material needs of our neighbor, there already lies the pledge of a possible relation to God, their spirit-bearing nature. ❖

by Mother Maria Skobtsova

my source: In CommunionThis is an extract from an essay, “The Second Gospel Commandment,” in Mother Maria Skobtsova: Essential Writings, published by Orbis. The book’s editor is Helene Klepinin Arjakovsky, daughter of Fr. Dmitri Klepinin, co-worker with Mother Maria, who died, as she did, in a concentration camp. The translation is by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky.

“The sign of those who have reached perfection is this: if ten times a day they are given over to be burned for the love of their neighbor, they will not be satisfied with that, as Moses, and the ardent Paul, and the other disciples showed. God gave His Son over to death on the Cross out of love for His creature. And if He had had something more precious, he would have given it to us, in order thereby to gain humankind. Imitating this, all the saints, in striving for perfection, long to be like God in perfect love for their neighbor.”

“No man dares to say of his love for his neighbor that he succeeds in it in his soul, if he abandons the part that he fulfills bodily, as well as he can, and in conformity with time and place. For only this fulfillment certifies that a man has perfect love in him. And when we are faithful and true in it as far as possible, then the soul is given power, in simple and incomparable notions, to attain to the great region of lofty and divine contemplation.”

These words from St. Isaac the Syrian, both from the Philokalia, justify not only active Christianity, but the possibility of attaining to “lofty and divine contemplation” through the love of one’s neighbor — not merely an abstract, but necessarily the most concrete, practical love. Here is the whole key to the mystery of human relations as a religious path.

For me these are truly fiery words. Unfortunately, in the area of applying these principles to life, in the area of practical and ascetic behavior toward man, we have much less material than in the area of man’s attitude toward God and toward himself. Yet the need to find some precise and correct ways, and not to wander, being guided only by one’s own sentimental moods, the need to know the limits of this area of human relations — all this is very strongly felt. In the end, since we have certain basic instructions, perhaps it will not be so difficult to apply them to various areas of human relations, at first only as a sort of schema, an approximate listing of what is involved.

Let us try to find the main landmarks for this schema in the triune makeup of the human being — body, soul, and spirit. In the area of our serving each of these main principles, ascetic demands and instructions emerge of themselves, the fulfillment of which, on the one hand, is unavoidable in order to reach the goal, and, on the other hand, is beyond one’s strength.

It seems right to me to draw a line here between one’s attitude toward oneself and one’s attitude toward others. The rule of not doing to others what you do not want done to yourself is hardly applicable in asceticism. Asceticism goes much further and sets much stricter demands on oneself than on one’s neighbors.

In the area of the relation to one’s physical world, asceticism demands two things of us: work and abstinence. Work is not only an unavoidable evil, the curse of Adam; it is also a participation in the work of divine economy; it can be transfigured and sanctified. It is also wrong to understand work only as working with one’s hands, a menial task; it calls for responsibility, inspiration, and love. It should always be work in the fields of the Lord.

Work stands at the center of modern ascetic endeavor in the area of man’s relation to his physical existence. Abstinence is as unavoidable as work. But its significance is to some degree secondary, because it is needed mainly in order to free one’s attention for more valuable things than those from which one abstains. One can introduce some unsuitable passion into abstinence — and that is wrong. A person should abstain and at the same time not notice his abstinence.

A person should have a more attentive attitude toward his brother’s flesh than his own. Christian love teaches us to give our brother not only material but spiritual gifts. We must give him our last shirt and our last crust of bread. Here personal charity is as necessary and justified as the broadest social work. In this sense there is no doubt that the Christian is called to social work. He is called to organize a better life for the workers, to provide for the old, to build hospitals, care for children, fight against exploitation, injustice, want, lawlessness.

In principle the value is completely the same, whether he does it on an individual or a social level; what matters is that his social work be based on love for his neighbor and not have any latent career or material purposes. For the rest it is always justified — from personal aid to working on a national scale, from concrete attention to an individual person to an understanding of abstract systems of the right organization of social life. The love of man demands one thing from us in this area: ascetic ministry to his material needs, attentive and responsible work, a sober and unsentimental awareness of our strength and of its true usefulness.

The ascetic rules here are simple and perhaps do not leave any particular room for mystical inspiration, often being limited merely to everyday work and responsibility. But there is great strength and great truth in them, based on the words of the Gospel about the Last Judgment, when Christ says to those who stand on His right hand that they visited Him in prison, and in the hospital, fed Him when He was hungry, clothed Him when He was naked. He will say this to those who did it either on an individual or on a social level.

Thus, in the dull, laborious, often humdrum ascetic rules concerning our attitude toward the material needs of our neighbor, there already lies the pledge of a possible relation to God, their spirit-bearing nature. ❖

Servant of God Dorothy Day

By

This essay by Jim Forest was originally written for The Encyclopedia of American Catholic History, published by the Liturgical Press; the text was updated for this web site in 2013. Jim Forest, once a managing editor of The Catholic Worker, is the author of All Is Grace: A Biography of Dorothy Day; and Living With Wisdom: A Biography of Thomas Merton. Both are published by Orbis Press.

“What you did to the least person, you did to me.”

— Jesus, Gospel of Matthew, 25:40

At their 2012 annual meeting, the Catholic bishops of the United States unanimously recommended the canonization of Dorothy Day, founder of the Catholic Worker movement. By then the Vatican had already given her the title “Servant of God,” the first step in formally recognizing Dorothy Day as a saint. On Ash Wednesday, 2013, preaching in Saint Peter’s Basilica in Rome, Pope Benedict XVI spoke of Dorothy Day as a model of conversion.

While awareness of her remarkable life has been growing steadily, she is at present still not widely known. Who was Dorothy Day? Why do so many people regard her as a model of sanctity for the modern world?

She was born into a journalist’s family in Brooklyn, New York, on November 8, 1897. After surviving the San Francisco earthquake in 1906, the Day family moved into a tenement flat on Chicago's South Side. It was a big step down in the world, made necessary because John Day was out of work. Day's understanding of the shame people feel when they fail in their efforts dated from this time.

Her father was passionately anti-Catholic, but in Chicago Day began to form positive impressions of Catholicism. Later in life she would recall her discovery of a friend's mother, a devout Catholic, praying at the side of her bed. Without embarrassment, she looked up at Day, told her where to find her daughter, and returned to her prayers. "I felt a burst of love toward her that I have never forgotten," Day recalled.

When John Day was appointed sports editor of a Chicago newspaper, the Day family moved into a comfortable house on the North Side. Here Dorothy began to read books that stirred her conscience. A novel by Upton Sinclair, The Jungle, inspired Day to take long walks in poor neighborhoods on Chicago's South Side, the area where much of Sinclair’s novel was set. These long walks were the start of a life-long attraction to areas many people avoid.

Day had a gift for finding beauty in the midst of urban desolation. Drab streets were transformed by pungent odors: geranium and tomato plants, garlic, olive oil, roasting coffee, bread and rolls in bakery ovens. "Here," she said, "was enough beauty to satisfy me."

Day won a scholarship that brought her to the University of Illinois campus at Urbana in the fall of 1914, but she was a reluctant scholar. Her reading drew her in a radical social direction. She avoided campus social life and insisted on supporting herself rather than living on money from her father.

Dropping out of college two years later, she moved to New York where she found a job reporting for The Call, the city's one socialist daily; she covered rallies and demonstrations and interviewed people ranging from butlers to revolutionaries.

She next worked for The Masses, a magazine that opposed American involvement in the European war. In September, the Post Office rescinded the magazine's mailing permit. Federal officers seized back issues, manuscripts, subscriber lists and correspondence. Five editors were charged with sedition. Day, the newest member of the staff, was able to get out the journal’s final issue.

Day’s conviction that the social order was unjust changed in no substantial way from her adolescence until her death, though she never identified herself with any political party.

In November 1917 Day went to prison for being one of forty women arrested in front of the White House for protesting women's exclusion from the electorate. Arriving at a rural workhouse, the women were roughly handled. The women responded with a hunger strike. Finally they were freed by presidential order.

Returning to New York, Day felt that journalism was a meager response to a world at war. In the spring of 1918, she signed up for a nurses’ training program in Brooklyn.

Her religious development was a gradual process. As a child she had attended services at an Episcopal Church in Chicago and been baptized. As a young journalist in New York, she would sometimes make late-at-night visits to St. Joseph's Catholic Church on Sixth Avenue. The Catholic climate of worship appealed to her. While she knew little about Catholic belief, Catholic spiritual discipline fascinated her. She saw the Catholic Church as "the church of the immigrants, the church of the poor."

In 1922, in Chicago working as a reporter, she roomed with three young women who went to Mass every Sunday and holy day and set aside time each day for prayer. It was clear to her that "worship, adoration, thanksgiving, supplication ... were the noblest acts of which we are capable in this life."

Her next job was with a newspaper in New Orleans. Living near St. Louis Cathedral, Day often attended evening Benediction services.

Back in New York in 1924, Day bought a beach cottage in the New York borough of Staten Island using money from the sale of movie rights for The Eleventh Virgin, an autobiographical novel she had written. She also began a four-year common-law marriage with Forster Batterham, a botanist she had met through friends in Manhattan. Batterham was an anarchist who opposed both marriage and religion. In a world of such cruelty, he found it impossible to believe in a God. By this time Day's belief in God was unshakable. It grieved her that Batterham didn't sense God's presence within the natural world. "How can there be no God," she asked, "when there are all these beautiful things?" Batterham’s irritation with her "absorption in the supernatural" often led them to quarrel.

What transformed everything for Dorothy was discovering she was pregnant. She had been pregnant once before, years earlier, as the result of a love affair with a journalist. This resulted in the great tragedy of her life, an abortion. The affair’s awful aftermath, Day concluded in the years following, had left her barren. "For a long time I had thought I could not bear a child, and the longing in my heart for a baby had been growing," she confided in her autobiography, The Long Loneliness. "My home, I felt, was not a home without one."

Her pregnancy with Batterham seemed to Day nothing less than a miracle. Batterham, however, did not rejoice. He didn't believe in bringing children into such a violent world.

On March 3, 1926, Tamar Theresa Day was born. Day could think of nothing better to do with the gratitude that overwhelmed her than arrange Tamar's baptism in the Catholic Church. "I did not want my child to flounder as I had often floundered. I wanted to believe, and I wanted my child to believe, and if belonging to a Church would give her so inestimable a grace as faith in God, and the companionable love of the Saints, then the thing to do was to have her baptized a Catholic."

Following Tamar's baptism, there was a permanent break with Batterham, a heart-breaking event for Day. On December 28, she was received into the Catholic Church. A period commenced in her life as she tried to find a way to bring together her religious faith and her radical social values.

In the winter of 1932 Day travelled to Washington, D.C., to report for two Catholic journals, Commonweal and America, on a radical protest called the Hunger March. Day watched the protesters parade down the streets of Washington carrying signs calling for jobs, unemployment insurance, old age pensions, relief for mothers and children, health care and housing. What kept Day in the sidelines was that she was a Catholic and the march had been organized by Communists, a party at war with not only capitalism but religion.

It was December 8, the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. After witnessing the march, Day went to the Shrine of the Immaculate Conception where she expressed her torment in prayer: "I offered up a special prayer, a prayer which came with tears and anguish, that some way would open up for me to use what talents I possessed for my fellow workers, for the poor."

Her prayer was quickly answered. The next day, back at her apartment in New York, Day met Peter Maurin, a French immigrant 20 years her senior, who was to change her life.

Maurin, a former Christian Brother, had left France for Canada in 1908 and later made his way to the United States. When he met Day, he was a handyman at a Catholic boys' camp in upstate New York, receiving meals, use of the chaplain's library, living space in the barn and occasional pocket money.

During his years of wandering, Maurin had come to a Franciscan attitude, embracing poverty as a vocation. His celibate, unencumbered life offered time for study and prayer, out of which a vision had taken form of a social order instilled with basic values of the Gospel "in which it would be easier for men to be good." A born teacher, he found willing listeners, among them George Shuster, editor of Commonweal magazine, who gave him Day's address.

As remarkable as the providence of their meeting was Day's willingness to listen. It seemed to her he was an answer to her prayers, someone who could help her discover what she was supposed to do.

What Day should do, Maurin said, was start a newspaper to publicize Catholic social teaching and promote steps to bring about the peaceful transformation of society. Day readily embraced the idea. If family past, work experience and religious faith had prepared her for anything, it was this.

Day found that the Paulist Press was willing to print 2,500 copies of an eight-page tabloid paper for $57. Her kitchen was the new paper's editorial office. She decided to sell the paper for a penny a copy, "so cheap that anyone could afford to buy it."

On May 1, the first copies of The Catholic Worker were handed out on Union Square.

Few publishing ventures meet with such immediate success. By December, 100,000 copies were being printed each month. Readers found a unique voice in The Catholic Worker. It expressed dissatisfaction with the social order and took the side of labor unions, but its vision of the ideal future challenged both urbanization and industrialism. It wasn't only radical but religious. The paper didn't merely complain but called on its readers to make personal responses.

For the first half year The Catholic Worker was only a newspaper, but as winter approached, homeless people began to knock on the door. Maurin's essays in the paper were calling for renewal of the ancient Christian practice of hospitality to those who were homeless. In this way followers of Christ could respond to Jesus' words: "I was a stranger and you took me in." Maurin opposed the idea that Christians should take care only of their friends and leave care of strangers to impersonal charitable agencies. Every home should have its "Christ Room" and every parish a house of hospitality ready to receive the "ambassadors of God."

Surrounded by people in need and attracting volunteers excited about ideas they discovered in The Catholic Worker, it was inevitable that the editors would soon be given the chance to put their principles into practice. Day's apartment was the seed of many houses of hospitality to come.

By the wintertime, an apartment was rented with space for ten women, soon after a place for men. Next came a house in Greenwich Village. In 1936 the community moved into two buildings in Chinatown, but no enlargement could possibly find room for all those in need. Mainly they were men, Day wrote, "grey men, the color of lifeless trees and bushes and winter soil, who had in them as yet none of the green of hope, the rising sap of faith."

Many of the down-and-out guests were surprised that, in contrast with most charitable centers, no one at the Catholic Worker set about reforming them. A crucifix on the wall was the only unmistakable evidence of the faith of those welcoming them. The staff received not salary, only food, board and occasional pocket money.

The Catholic Worker became a national movement. By 1936 there were thirty-three Catholic Worker houses spread across the country. Due to the Great Depression, there were plenty of people needing them.

The Catholic Worker attitude toward those who were welcomed wasn't always appreciated. These weren't the "deserving poor," it was sometimes objected, but drunkards and good-for-nothings. A visiting social worker asked Day how long the "clients" were permitted to stay. "We let them stay forever," Day answered.. "They live with us, they die with us, and we give them a Christian burial. We pray for them after they are dead. Once they are taken in, they become members of the family. Or rather they always were members of the family. They are our brothers and sisters in Christ."

Some justified their objections with biblical quotations. Didn't Jesus say that the poor would be with us always? "Yes," Day once replied, "but we are not content that there should be so many of them. The class structure is our making and by our consent, not God's, and we must do what we can to change it. We are urging revolutionary change."

The Catholic Worker has also experimented with farming communes. In 1935, a house with a garden was rented on Staten Island. Soon after came Maryfarm in Easton, Pennsylvania, a property finally given up because of strife within the community. Another farm was purchased in upstate New York near Newburgh. Called the Maryfarm Retreat House, it was destined for a longer life. Later came the Peter Maurin Farm on Staten Island, which later moved to Tivoli and then to Marlborough, both in the Hudson Valley. Day came to see that the vocation of the Catholic Worker was not so much to found model agricultural communities, though several have been productive and long-lasting, as rural houses of hospitality.

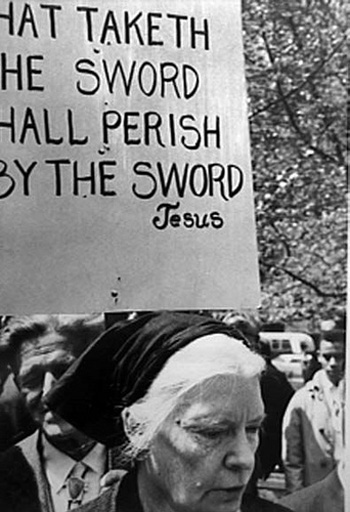

What got Day into the most trouble was pacifism. A nonviolent way of life, as she saw it, was at the heart of the Gospel. She took as seriously as the early Church the command of Jesus to Saint Peter: "Put away your sword, for whoever lives by the sword shall perish by the sword."

For many centuries the Catholic Church had accommodated itself to war. Popes had blessed armies and preached Crusades. In the thirteenth century Saint Francis of Assisi had revived the pacifist way, but by the twentieth century, it was unknown for Catholics to take such a position.

The Catholic Worker's first expression of pacifism, published in 1935, was a dialogue between a patriot and Christ, the patriot dismissing Christ's teaching as a noble but impractical doctrine. Few readers were troubled by such articles until the Spanish Civil War in 1936. The fascist side, led by Franco, presented itself as defender of the Catholic faith. Nearly every Catholic bishop and publication rallied behind Franco. The Catholic Worker, refusing to support either side in the war, lost two-thirds of its readers.

Those backing Franco, Day warned early in the war, ought to "take another look at recent events in [Nazi] Germany." She expressed anxiety for the Jews and later was among the founders of the Committee of Catholics to Fight Anti-Semitism.

Following Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor and America's declaration of war, Dorothy announced that the paper would maintain its pacifist stand. "We will print the words of Christ who is with us always," Day wrote. "Our manifesto is the Sermon on the Mount." Opposition to the war, she added, had nothing to do with sympathy for America's enemies. "We love our country.... We have been the only country in the world where men and women of all nations have taken refuge from oppression." But the means of action the Catholic Worker movement supported were the works of mercy rather than the works of war. She urged "our friends and associates to care for the sick and the wounded, to the growing of food for the hungry, to the continuance of all our works of mercy in our houses and on our farms."

Not all members of Catholic Worker communities agreed. Fifteen houses of hospitality closed in the months following the U.S. entry into the war. But Day's view prevailed. Every issue of The Catholic Worker reaffirmed her understanding of the Christian life. The young men who identified with the Catholic Worker movement during the war generally spent much of the war years either in prison or in rural work camps. Some did unarmed military service as medics.

The world war ended in 1945, but out of it emerged the Cold war, the nuclear-armed "warfare state," and a series of smaller wars in which America was often involved.

One of the rituals of life for the New York Catholic Worker community beginning in the late 1950s was the refusal to participate in the state's annual civil defense drill. Such preparation for attack seemed to Day part of an attempt to promote nuclear war as survivable and winnable and to justify spending billions on the military. When the sirens sounded June 15, 1955, Day was among a small group of people sitting in front of City Hall. "In the name of Jesus, who is God, who is Love, we will not obey this order to pretend, to evacuate, to hide. We will not be drilled into fear. We do not have faith in God if we depend upon the Atom Bomb," a Catholic Worker leaflet explained. Day described her civil disobedience as an act of penance for America's use of nuclear weapons on Japanese cities.

The first year the dissidents were reprimanded. The next year Day and others were sent to jail for five days. Arrested again the next year, the judge jailed her for thirty days. In 1958, a different judge suspended the sentence. In 1959, Day was back in prison, but only for five days. Then came 1960, when instead of a handful of people coming to City Hall Park, 500 turned up. The police arrested only a few, Day conspicuously not among those singled out. In 1961 the crowd swelled to 2,000. This time forty were arrested, but again Day was exempted. It proved to be the last year of dress rehearsals for nuclear war in New York.

Another Catholic Worker stress was the civil rights movement. As usual Day wanted to visit people who were setting an example and therefore went to Koinonia, a Christian agricultural community in rural Georgia where blacks and whites lived peacefully together. The community was under attack when Day visited in 1957. One of the community houses had been hit by machine-gun fire, and Ku Klux Klan members had burned crosses on community land. Day insisted on taking a turn at the sentry post. Noticing that an approaching car had reduced its speed, she ducked just as a bullet struck the steering column in front of her face.

Concern with the Church's response to war led Day to Rome during the Second Vatican Council, an event Pope John XXIII hoped would restore "the simple and pure lines that the face of the Church of Jesus had at its birth." In 1963 Day was one of fifty "Mothers for Peace" who went to Rome to thank Pope John for his encyclical Pacem in Terris. Close to death, the pope couldn't meet them privately, but at one of his last public audiences blessed the pilgrims, asking them to continue their labors.

In 1965, Day returned to Rome to take part in a fast expressing "our prayer and our hope" that the Council would issue "a clear statement, `Put away thy sword.'" Day saw the unpublicized fast as a "widow's mite" in support of the bishops' effort to speak with a pure voice to the modern world.

The fasters had reason to rejoice in December when the Constitution on the Church in the Modern World was approved by the bishops. The Council described as "a crime against God and humanity" any act of war "directed to the indiscriminate destruction of whole cities or vast areas with their inhabitants." The Council called on states to make legal provision for conscientious objectors while describing as "criminal" those who obey commands which condemn the innocent and defenseless.

Acts of war causing "the indiscriminate destruction of ... vast areas with their inhabitants" were the order of the day in regions of Vietnam under intense U.S. bombardment in 1965 and the years following. Many young Catholic Workers went to prison for refusing to cooperate with conscription, while others did alternative service. Nearly everyone in Catholic Worker communities took part in protests. Many went to prison for acts of civil disobedience.

Probably there has never been a newspaper so many of whose editors have been jailed for acts of conscience. Day herself was last jailed in 1973 for taking part in a banned picket line in support of farmworkers. She was seventy-five.

Day lived long enough to see her achievements honored. In 1967, when she made her last visit to Rome to take part in the International Congress of the Laity, she found she was one of two Americans — the other an astronaut — invited to receive Communion from the hands of Pope Paul VI. On her 75th birthday the Jesuit magazine America devoted a special issue to her, finding in her the individual who best exemplified "the aspiration and action of the American Catholic community during the past forty years." Notre Dame University presented her with its Laetare Medal, thanking her for "comforting the afflicted and afflicting the comfortable."

Among those who came to visit her when she was no longer able to travel was Mother Teresa of Calcutta, who had once pinned on Day's dress the crucifix normally worn only by fully professed members of the Missionary Sisters of Charity.

Long before her death on November 29, 1980, Day found herself regarded by many as a saint. No words of hers are better known than her brusque response, "Don't call me a saint. I don't want to be dismissed so easily." Nonetheless, having herself treasured the memory and witness of many saints, she is a candidate for inclusion in the calendar of saints. Cardinal John O’Connor, Archbishop of New York, launched the canonization process in 1997, the hundredth anniversary of Day’s birth.

"If I have achieved anything in my life," she once remarked, "it is because I have not been embarrassed to talk about God."

* * *

Bibliography:

Robert Coles, Dorothy Day: A Radical Devotion (Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley, 1987)

Tom Cornell, Robert Ellsberg and Jim Forest, editors, A Penny a Copy: Writings from The Catholic Worker (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1995)

Dorothy Day, The Long Loneliness. (Chicago: Saint Thomas More Press, 1993)

Robert Ellsberg, editor, Dorothy Day: Selected Writings (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 1992)

Robert Ellsberg, editor, The Duty of Delight: The Diaries of Dorothy Day (Marquette University Press, 2007)

Robert Ellsberg, editor, All the Way to Heaven: The Selected Letters of Dorothy Day (Marquette University Press, 2010)

Jim Forest, All Is Grace: a biography of Dorothy Day (Maryknoll, NY: Orbis, 2011)

William Miller, Dorothy Day: A Biography (New York: Harper & Row, 1982)

No comments:

Post a Comment