THOMAS MERTON ON FATHER ALEXANDER SCHMEMANN

There were a few comments a while ago that raised the topic of Thomas Merton’s relationship with Orthodoxy, and TheraP mentioned a review that he had written on Father Alexander Schmemann’s work. I had read the review in Monastic Studies (no. 4, Advent 1966: 105-115) earlier this year, and since reading Father Schmemann’s The Eucharist Sacrament of the Kingdom: Sacrament of the Kingdom, had been wanting to return to it. TheraP drew my attention to the fact that it had also been included in the volume Merton & Hesychasm: The Prayer of the Heart & the Eastern Church (The Fons Vitae Thomas Merton series), and this weekend I have been visiting friends who have this book. The whole book looks fascinating and there are several other essays that I have dipped into and would like to read properly, both by Merton and by people like Metropolitan Kallistos Ware, Canon A.M. Allchin, Rowan Williams and Jim Forest. But I re-read his review of Father Schmemann’s Sacraments and Orthodoxy and of Ultimate Questions. Here are a few extracts:

…Sacraments and Orthodoxy, a powerful, articulate and indeed creative essay in sacramental theology which rival Schillebeeckx and in some ways excels him. Less concerned than Schillebeeckx with some of the technical limitations of Catholic sacramental thought, Schmemann can allow himself to go the very root of the subject without having to apologize for his forthrightness or for his lack of interest in trivialities.

Let the reader be warned. If he is now predisposed to take a comfortable, perhaps exciting mysterious, excursion into the realm of a very “mystical” and highly “spiritual” religion, the gold-encrusted cult thick with the smoke of incense and populated with a legion of gleaming icons in the sacred gloom, a “liturgy which to be properly performed requires not less than twenty-seven heavy liturgical books,” he may find himself disturbed by Fr. Schmemann’s presentation. Certainly, Sacraments and Orthodoxy will repudiate nothing of the deep theological and contemplative sense of Orthodox faith and worship. But the author is intent on dispelling any illusions about the place of “religion” in the world of today. In fact, one would not suspect from the title of this book, it is one of the strongest and clearest statements of position upon this topic of the Church and the world. (474) ….

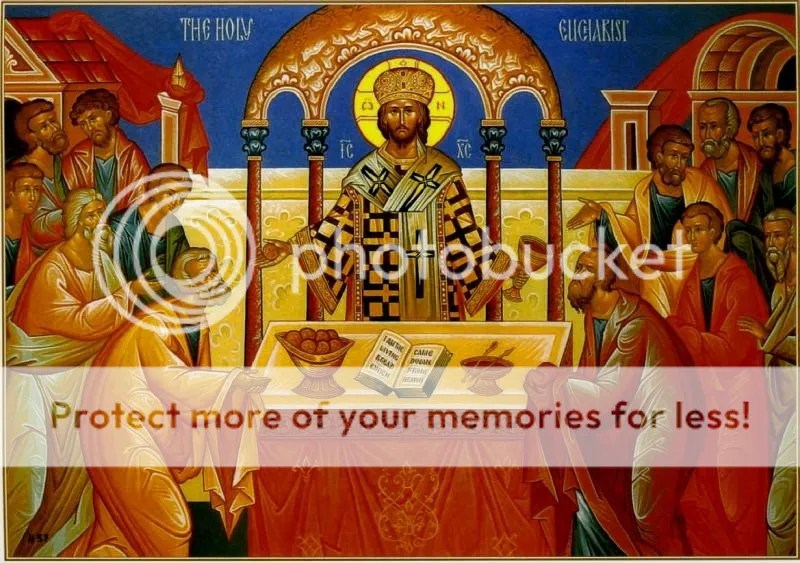

The heart of Fr. Schmemann’s argument is that the Church’s vocation to worship and witness in the world is a vocation to a completely eucharistic view of all creation, a view which, far from setting aside worship and confining it to a special limited area of cult, sees and celebrates the world itself as “meaningful because it is the sacrament of God’s presence.” “Life itself,” he continues, in terms that would perhaps disconcert those habituated to the strict logical categories of scholastic thought, “is worship.” “We were created as celebrants of the sacrament of life.” Man is regarded by Fr. Schmemann as naturally homo adorans, the high priest of creation, the “priest of the cosmic sacrament” (the material world).

Even in his most fallen and alienated state, far from the Church and from the vision of God, man remains hungry for the eucharistic life. He longs, unconsciously, to enter into the sacred banquet, the wedding feast, the celebration of the victory of life over death. But his tragedy is that he is caught in a fallen world which is confused and opaque, which is no longer seen as “sacrament” but accepted as an end in itself. That is to say, it is no longer seen as a gift to be received from God in gladness and returned to Him in praise and celebration. It is accepted on its own terms as an area in which the individual ego engages in a desperate struggle against time to attain some measure of happiness and self-fulfillment before death inevitably ends everything. Even when he seeks a “religious” answer to his predicament in the fallen world, man finds himself struggling to produce “good behavior” to make things come out so that he will have happiness in the world – or, failing that, in the next.

Even Christianity sometimes ends up by being a pseudo Christian happiness cult, a judicious combination of ethical tranquilizing and sacramental happy making, plus a dart of art and a splash of political realism (a crusade!). This of course calls for specialists in counselling, men trained to give the right answers, engineers of uplift! “Adam failed to be the priest of the world and because of this failure the world ceased to be the sacrament of divine love and presence and became ‘nature’. And in this ‘natural’ world, religion became an organized transaction with the supernatural and the priest was set apart as the transactor.” It is precisely from this state of affairs that secularism arises: “Clericalism is the father of secularism.”

True to the tradition of the Greek Fathers, Fr. Schmemann sees all life as “cosmic liturgy,” and views man as restored by the Incarnation to his place in that liturgy, so that, with Christ and in Christ, he resumes his proper office as high priest in a world that is essentially liturgical and eucharistic. The function of the Church (and of the sacraments) is then to lead all mankind back on a sacred journey to reconciliation with the Father. In the liturgy, the Church calls together all men and invites them to join ranks with her and, in answer to the “tidings of great joy,” to go out in procession to meet the Lord and enter with Him into the wedding banquet which is His Kingdom of joy and love. (477-478)

Dom André Louf on the Liturgy of the Heart

This is my report of a public lecture given by Dom André Louf in Saint Andrew’s Orthodox Parish, Ghent, as part of the colloquium on the Syrian Fathers. Please note my earlier disclaimer on the accuracy of my reporting and translations, something that may particularly apply to my reporting of this talk as I was tired and my note taking somewhat uneven! I also have the impression that Dom André skipped over some sections due to time constraints. Once the text is published I may consider doing an English translation for publication somewhere.

The late Dom André Louf, ocso was abbot emeritus of the abbey of Mont des Cats in France and author of several books, including Teach us to Pray, The Cistercian Way and Grace can do more. He became a hermit and translated Syrian texts. He was responsible for the French translation of the second series of St Isaac’s homilies.

The phrase “liturgy of the heart” is not found in Scripture but it finds its roots in the reference in 1 Peter 3, 4 in which Peter speaks of the “ho kruptos tès kardias anthropos” (“interior disposition of the heart”, NJB, or “inner self”, NRSV), literally the hidden human being of the heart.

This interior human heart is viewed by Scripture in rather ambiguous terms. It may be orientated to wicked schemes (Gen. 6, 5), it may be hard and even turned to stone (Ex. 7, 3) but it may also be softened and humbled (2 K 22, 19) and especially contrite (Ps 50, 17) and to be healed by God (Ps 147, 3). God reproaches the uncircumcised heart (Lv 26,41; Dt 10, 16; 30, 6; Jer. 9, 26). It is on the tablets of the heart that God will write a new law (Pr. 3,3; 7, 3). With the prophet Ezekiel God promises to change the heart of stone to a heart of flesh (11, 19; 36, 26). Solomon will plead for such a heart at the beginning of his reign (1 K. 3, 9) and advises his son David to watch over his heart, for from the heart come the wellsprings of life. (Pr. 4, 23)

Jesus’ teaching on interiority lies within this tradition. He calls the pure of heart blessed, and contrasts them with closed hearts and hearts which bring forth evil (Mt. 15, 18). “Good people draw what is good from the store of goodness in their hearts; bad people draw what is bad from the store of badness. For the words of the mouth flow out of what fills the heart.” (Lk 6, 45) It is in the heart that one can ponder the Word as Mary did (Lk 2, 19) for as Paul reminds us (quoting Deuteronomy) “the word is very near to you; it is in your mouth and in your heart.” (Rm 10, 8) It is likewise the hearts that burned within when Jesus appeared to the disciples on the road to Emmaus. (Lk 24, 32) The heart is also the temple of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor. 6, 19), a temple in which an interior liturgy is celebrated (Ep. 5, 19).

Such are the biblical illusions that are summed up in the phrase “ho kruptos tès kardias anthropos” of 1 Peter 3, 4.

Paul contrasts this “inner nature” with our “outer nature” that is decaying. (2 Cor. 4, 16-18).

Could it be that this most interior reality is frightening for our contemporaries? We can even ask why the text from Ephesians 5, 19 “sing and praise in your hearts” is often translated today as “with all your heart”. While this might be linguistically defensible, no single Church Father interpreted in this way, for they understood it as alluding to the interior liturgy of the heart, which runs as a thread through the entire patristic tradition.

This liturgy of the heart is something which the Holy Spirit is constantly praying in every baptised person, whether we are aware of it or not. “…the Spirit too comes to help us in our weakness, for, when we do not know how to pray properly, then the Spirit personally makes our petitions for us in groans that cannot be put into words” (Rm 8, 26). This prayer is something which all Christians carry in their hearts, whether they are aware of it or not. In the deepest part of our being we find grace and prayer, and even if we are unaware of it the Spirit is praying “Abba, Father” in us.

If this is true, then the purpose of prayer is simply to bring us into contact with this prayer that is already being prayed in us. Any “methods” or “techniques” of prayer, or the disciplines of turning inwards and quieting the heart, only exist to help this unconscious prayer to become conscious. This is, moreover, an unconsciousness that is much deeper than the psychological unconscious which is becoming better known today. This is an unconscious that touches the very roots of our being. It is metaphysical and meta-psychological, for it is concerned with that place where our being is immersed in God and repeatedly springs up from God. This is the place where prayer does not stop, the domus interior or templum interius as it was called in the Middle Ages.

Most of the time we are not conscious of the prayer taking place in this inner temple. We can only believe in it with a growing certainty, and trust that God will lift the veil and allow a little of this unconscious prayer to emerge to consciousness. Sometimes this is merely a sudden illumination, a passing light which clarifies aspects of our existence and which never leaves us even in the midst of new periods of dryness. More often, though, it involves a slow and patient process in which something emerges towards the surface, awakening a new sensitivity or what Ruusbroec called a “feeling above all feelings”.

While it is certainly true that some circumstances are more conducive to this process than others, and thus silence, simplicity and asceticism can be important preparations for prayer, Christian prayer is never determined by such preparations. God allows prayer to arise in us “when He wills, as He wills and where He wills” as Ruusbroec says. For God is always greater than our heart and remains the only Master of our prayer. Prayer is totally gratuitous although we need to persevere in times of trial.

In persevering in times of dryness and crisis, in seeing all of our efforts ending in dead ends, and in being confronted with our own weakness that we receive the grace of recognising ourselves for the sinners who we really are. It is precisely in encountering ourselves as sinners that we also encounter the grace of God. John Cassian tells us:

Let us in this way learn in all that we do to perceive both our own weakness and the grace of God at the same time, so that we are able to proclaim every day with the saints: “They have pushed me down to make me fall, but the Lord has supported me.”

What is our task as human beings in this process? It has only one name, and that is humility. Cassian describes this as “every day humbly following the grace of God that draws us.” Learning humility, even, or perhaps especially, through failure, is the greatest lesson that we can learn. As one of the Fathers said: “I would rather choose a defeat humbly accepted than a victory achieved with pride.”

This is the heart of the process, the point at which it is possible for a new sensitivity to be born, and it can be characterised by confusion and doubt. The old Christian literature referred to this with the imagery of “diatribe tès kardias” or “contritio cordis” or “contrition mentis”. It would be good to try and recapture something of the jolting language which has been lost in later translations, for this is not simply about “contrition” as we have come to understand it in recent spiritual literature but rather about a “broken” and “pulverised” heart that has literally been shattered. In this we are reminded of the utter poverty of the Christian. Isaac of Nineveh writes:

Believe me, my brother, you have not yet understood the power of temptation, nor the subtlety of its guiles. One day the experience will teach it to you and you will see yourself as a child who no longer knows where to look. All your knowledge will be nothing more than confusion, like that of a little child. Your spirit which appeared to be so firmly anchored in God, your precise knowledge, your balanced thought world, they will all be submerged in an ocean of doubt. Only one thing will be able to help you and will conquer them, namely, humility. Once you have grasped this, their power will disappear.

And, as Saint Basil tells us, “Often it is humility that saves someone who has sinned frequently and heavily.”

This is a painful pedagogy. Instead of fleeing from it, we are called to follow its trajectory and to make it our own, not out of masochism, but because one senses that it is the secret source of the only true life. In biblical language we can say that it is here that the heart of stone becomes broken so that may be made into a heart of flesh.

If such temptation does lead to sin then this is not due to a lack of generosity, but rather to a lack of humility. And sin offers us the chance to discover the narrow and low gate that leads to the Kingdom. Indeed, it could be that the most dangerous temptation is not the temptation that leads to sin, but rather the temptation that follows sin, namely the temptation of despair. It is only through eventually learning humility that we can escape this. And through this we learn the gift of mercy. Isaac of Nineveh writes:

Who can still be brought into confusion by the memory of his own sins…? Will God forgive me these things whose memory so torments me? Things that I have an aversion to but which I nevertheless slip towards. And when I have done them their memory torments me more than a scorpion’s bite. I detest them and yet I find myself in their midst, and when I feel pain and sorrow over them I continue to seek them our – oh unhappy person that I am! … This is how many God fearing people think, people who desire virtue but whose weakness forces them to take into account their own frailty: they live continually imprisoned between sin and remorse. … Nevertheless, do not doubt your salvation … His mercy is much greater than you can imagine, and His grace is greater than you can dare to ask for. He looks only for the slightest sorrow …

How does this transition occur? We cannot predict when or how we will be brought into this interiority, but when it happens we know that we are not in control. We become aware of a new sensitivity and of a peace that cannot deceive us, of a centeredness and of a prayer that emerges of its own accord. There are certain times or places in our lives at which we find ourselves closer to this breakthrough, times or places where one is closer to its becoming a reality.

One of these privileged places is always the listening to the Word of God in Scripture. Scripture has the power to shake our heart awake, to drill through it, batter it open, so that prayer can spring up. Likewise, sickness, the death of someone close to us, and great temptations are favourable moments in which our longing for God means that we are more open to Him.

We find all these favourable moments brought together in the celebration of the Liturgy. The Church has instinctively sensed the mysterious affinity between the external Liturgy celebrated in churches of stone and the Liturgy celebrated in the deepest depth of each baptised Christian. The Church has learnt through experience how to harmonise these two liturgies of the praying Christian.

In our contemporary world we find conflicting desires that make such interiority difficult. On the one hand there is a desire for such interiority, but, on the other hand, there is much that makes it difficult for us to surrender to it. We cannot blame this on God, who desires to give Himself to us. But the children of the Church are also the children of their culture and find themselves in a cultural transition. It may be that there are elements in our culture, both of yesterday and of today, that make it more difficult to find real interiority. Or it may be that there are elements that at first sight make it easier to enter into such interiority – such as the reactions to the dangers below found in some youth movements which are orientated to religious experience – but which are really illusory.

We can name three negative influences in the religious culture of the last decades. The first is to reduce the Gospel to an ideology, which is more orientated to thought patterns than to life. The Second is to reduce the Gospel to activism, in which one loses contact with one’s inner life and reduces the Gospel to marketing. And the third is to reduce the Gospel to moralism in which a skewed moral vision which can hinder authentic interior experience.

[Dom André skipped over the first two points - I suspect due to time pressure - and concentrated on the third.]

The life of the Holy Spirit in us seeks ways to express itself in concrete circumstances, but if it is authentic this is, in the first place, expressed in spontaneity, freedom and deep joy. In a second moment we can describe Christian behaviour from without, such as Paul does in his teaching on the fruits of the Spirit. Such a moral pedagogy should help to bring us into contact with the inner experience and make us sensitive to the workings of the Spirit. However, it has not always been so simple. Influenced by cultural ethical schemas, morality has sometimes lost its way in abstract and absolutised studies of human behaviour which resulted in an idealised set of rules which one had to adhere to.

This is not to deny the need for ethical norms, but rather to recognise their pitfalls, and in particular the danger of separating interior disposition and exterior action. This can result in two dangers. Firstly, it can result in someone who is unable to live up to the expectations of the law becoming caught up in a spiral of guilt. The law accuses, but Jesus refuses to accuse and has come to free us from guilt. Secondly, it can result in a more subtle and dangerous danger, that of an easy conscience and apparent perfection in which one becomes cut off from the liberating action of the Holy Spirit.

Jesus avoided both of these dangers. He never drove sinners to despair and he confronted the conceit of the Pharisees. He did not come for the righteous, but for sinners.

To speak about sin and sinners is a problem in our contemporary world, which does not know how to deal with sin and sinners. Yet there is a link between sin and our access to the inner way. We may be desperate sinners who are burdened with guilt feelings. Or we may play the role of freed sinners who dream of a morality without sin. Or – and this is the worst – we may be the incurably righteous who look down on sinners. Insofar as we belong to one of these categories we are not able to access the inner way.

God longs for sinners as a Father longs for his lost son. For genuine sinners, who do not seek to gloss over or excuse their weakness, but who have become reconciled with their weakness and who rely on God’s mercy. At the moment that one receives God’s forgiveness, someone is opened up in one’s heart so that one’s heart can become transformed from a heart of stone to a heart of flesh. Sin no longer drags one down and bruises one, but has rather become the door to the depths of our heart for it leads us to the knowledge of the merciful Father.

The Heart

“At the center of our being is a point of nothingness which is untouched by sin and by illusion, a point of pure truth, a point or spark which belongs entirely to God, which is never at our disposal, from which God disposes of our lives, which is inaccessible to the fantasies of our own mind or the brutalities of our own will. This little point of nothingness and of absolute poverty is the pure glory of God in us. It is so to speak His name written in us, as our poverty, as our indigence, as our dependence, as our sonship. It is like a pure diamond, blazing with the invisible light of heaven. It is in everybody, and if we could see it we would see these billions of points of light coming together in the face and blaze of a sun that would make all the darkness and cruelty of life vanish completely ... I have no program for this seeing. It is only given. But the gate of heaven is every- where.” ― Thomas Merton, Conjectures of a Guilty Bystander

Ten Days on Mount Athos

(Orthodox)

Seeking God: Benedictines of Norcia

(Catholic)

No comments:

Post a Comment