Glory be to God for dappled things –

For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow;

For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;

Landscape plotted and pieced – fold, fallow, and plough;

And áll trádes, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange;

Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)

With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:

Praise him.

my source: Called to Communion

This is a guest post by Michael Rennier. Michael received a BA in New Testament Literature from Oral Roberts University in 2002 and a Master of Divinity from Yale Divinity School in 2006. He served the Anglican Church in North America as the Rector of two parishes on Cape Cod, Massachusetts for five years. After discerning a call to conversion, Michael and his family moved to St. Louis. On October 16th, 2011, he and his wife were received into full communion with the Catholic Church by the Most Rev. Robert Carlson, Archbishop of St. Louis. Michael tells the story of his conversion in “Into the Half-Way House: The Story of an Episcopal Priest.” He now works for the Archdiocese of St. Louis.

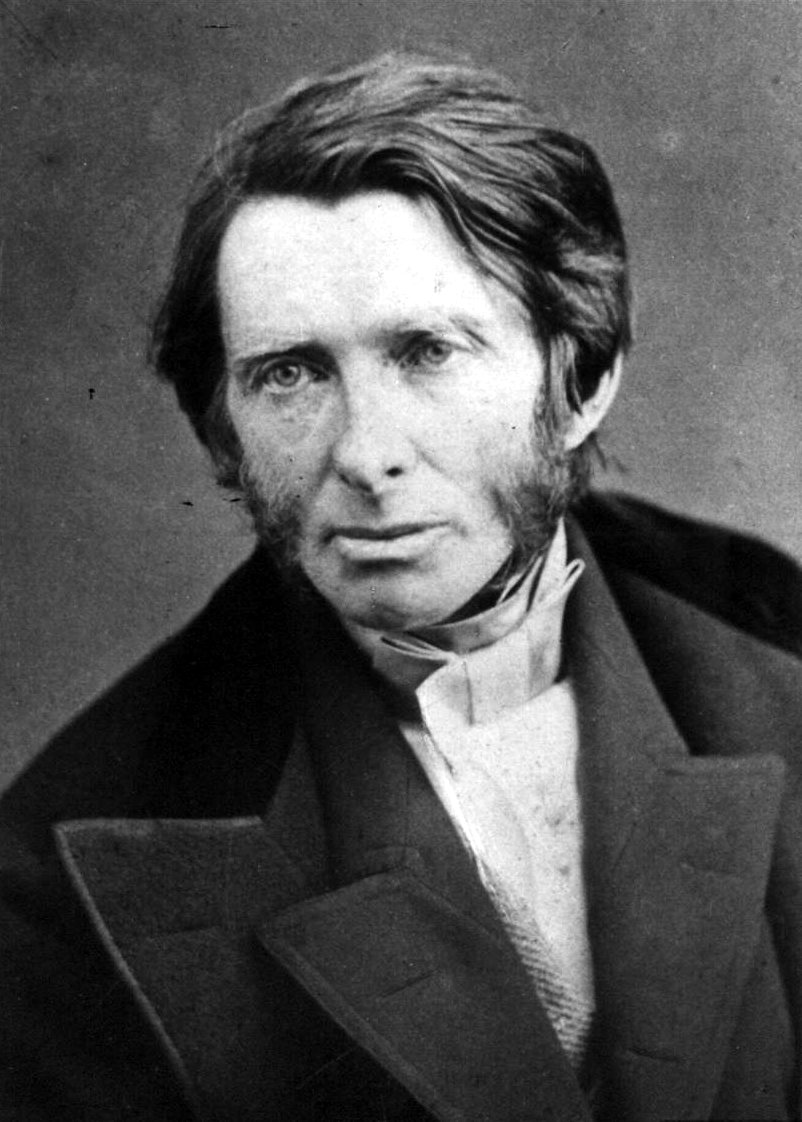

Gerard Manley Hopkins

“TRUMPERY, MUMMERY, AND G.M. HOPKINS FLUMMERY? …REMOVED TO THE OTHER SIDE OF THE WAY” So Gerard Manley Hopkins laughingly writes to his concerned friend Robert Bridges in 1866. Knowing that his impending conversion to the Catholic faith will damage his position at Oxford and change his life forever, laughter is all Hopkins can manage. Not that he is insincere. Rather, his studied unseriousness is a learned reaction from John Henry Newman, who upon hearing of the difficulties Hopkins is about to get himself into, can only laugh and remark that, indeed, there is “no way out” of coming to the Church. We would do better to interpret the laughter as intense, pure happiness. Hopkins himself remarks on this point over and over again. After having felt as an exile and as “a penitent waiting for admission to the Catholic Church” for a good long while, he has finally made up his mind. Consequently, the cares of the world have slipped entirely away.

Even post-Tractarian Oxford was not a hospitable place for a convert. In fact, Hopkins is ruining his life. Such are the words that his father uses to describe the situation. Here is his eldest son, who after a spotless course at Oxford, is preparing to leave it all behind for what appears to be a passing fancy, a youthful attraction. In hindsight, we know that Hopkins’s conversion comes from a far deeper place. His love for the Catholic Church never wavers. Indeed, his career prospects disappear and he, like all other Catholics, is banned from government posts. He never advances far in the Catholic Church as a priest. He never feels comfortable in his role as a pastor. The Society of Jesus, of which he becomes a member, never finds him entirely satisfactory. He ends his life in Ireland as a college teacher; at that time hardly considered a successful conclusion. Certainly Hopkins himself feels the strain of being sent away, as he writes in "To Seem the Stranger", “I am in Ireland now; now I am at a third / remove.” The enjambment of the word “remove” emphasizing the physicality of his estrangement is a nice touch from the poetic genius who was read and appreciated by exactly two people at the time of his death. And yet, his last words as he lies dying at a young age are “I am so happy. I am so happy.”

What is it that compels this bright young Oxford man, impels him inexorably onward to the Catholic Church? How is it that the obstacles imagined and the failures experienced never shake his happiness?

There is a simple answer:

Beauty.

Hopkins is a man who recklessly and relentlessly searches for beauty. Those around him, perhaps, look at his thirst for beauty as an aesthete’s dandyish affectation, hardly a matter to ruin one’s life over. But for Hopkins, beauty is a far more serious matter. It is not a passing fancy. It is not an effete gloss on the surface of deeper, serious thoughts. To him, beauty is immortal; the sparkling diamond of the divine by which all other things are made to shine. His father notices the attitude, admitting that he has noticed his son’s “growing love for high ritual.” His father, however, understands this to be mere attraction to the liturgy itself. In reply, Hopkins sets the matter straight by noting that the Tractarian movement has had its effect; when it comes to surface aesthetics, the Anglican Church wins hands down over the Romans. This, however, is not what compels him. Instead he notes that Catholicism is meant “to be loved — its consolations, its marvelous ideal of holiness, the faith and devotion of its children, its multiplicity, its array of saints and martyrs, its consistency and unity, its glowing prayers, the daring majesty of its claims.” These are not the words of a mere enthusiast attracted to smells and bells. These are the words of a man who has recognized true beauty. It is this which compels him onward.

In the poem "Duns Scotus’s Oxford", Hopkins writes,

this air I gather and I release

he lived on; these weeds and waters, these walls are what

He haunted who of all men most sways my spirits

to peace;

The allusion in the poem is first and foremost to the man who was a great promoter of the Immaculate Conception of the Blessed Virgin Mary, the man who “fired France for Mary without spot.” Beyond this specifically we find brought together two formative influences on Hopkins: there is Oxford with her “coped and poised powers” and there is Duns Scotus and his metaphysics.

To understand what is so compelling about beauty, we must start at Oxford. It is here that Hopkins first develops a particular sensitivity to beauty. He becomes a disciple of Ruskin while at Oxford, at least partially through the influence of the artist Walter Pater. Ruskin teaches that beauty is found in close attention to every particular of a thing, trying to get at the essence of it. He holds that if an artist can paint a leaf, he can paint the world. The role of the artist is to describe his subject in accurate detail. As the inner form, or the inscape (a Hopkins neologism), of the subject comes out, the artist beholds the divine and is beheld by the divine. There is a sort of communion here that ties the perceived and the perceiver together.

In "Wreck of the Deutschland" we see how a few years after conversion Hopkins explicitly connects beauty to the theological. Through finding the instress of a tempestuous sky he finds that he meets God.

I kiss my hand

To the stars, lovely-asunder

Starlight, wafting him out of it; and

Glow, glory in thunder;

Kiss my hand to the dappled-with-damson west:

Since, tho’ he is under the world’s splendour and wonder,

His mystery must be instressed, stressed;

For I greet him the days I meet him, and bless when I understand

Hopkins might not always recognize exactly how the beauty of Christ is present in the world, but theologically he knows that if anything is beautiful it is so by the mystery of God’s presence. The world is God-shaped; fathered forth by “the one whose beauty is past change.”

In addition to Ruskin, there is Duns Scotus. Hopkins is a close reader of Scotus already at Oxford and the influence is easy to recognize in his theory of intuitive cognition, which says that our instincts often point to the truth even if we can’t explain why or how. The beauty of poetry, for instance, is located in that realm of intuition. This is reflected in language, which Hopkins employs by taking apart. His poems aren’t just a string of affected metaphors. Rather, they are an attempt at using language in such a way that it is almost musical, or pre-cognitive. It is word placed in the unique context of Jesus Christ the Word. He is trying to find that precognitive moment, the inscape of the thing, and by so doing he is locating an inexpressible beauty and giving it back to God as worship. Hopkins affectingly writes in a minor poem, “give beauty back, beauty, beauty, beauty, back to God, beauty’s self and beauty’s giver.” Beauty shows us truth and the truth is Jesus.

Thus, after his conversion, Hopkins’s conception of beauty finds a natural development in the thought of St. Ignatius of Loyola. I would argue that the Society of Jesus never was a good fit for Hopkins temperamentally or professionally. He takes vows anyway, drawn in by the tender heart of St. Ignatius whose theme on the practice of the presence of Christ must have been irresistible to a man such as Hopkins.

For instance, notice how the Incarnational worldview of St. Ignatius comes through in The Windhover.

To Christ our Lord

I caught this morning morning’s minion, king-

dom of daylight’s dauphin, dapple-dawn-drawn Falcon, in his riding

Of the rolling level underneath him steady air, and striding

High there, how he rung upon the rein of a wimpling wing

In his ecstasy! then off, off forth on swing,

As a skate’s heel sweeps smooth on a bow-bend: the hurl and gliding

Rebuffed the big wind. My heart in hiding

Stirred for a bird, – the achieve of, the mastery of the thing!

Brute beauty and valour and act, oh, air, pride, plume, here

Buckle! AND the fire that breaks from thee then, a billion

Times told lovelier, more dangerous, O my chevalier!

No wonder of it: sheer plod makes plough down sillion

Shine, and blue-bleak embers, ah my dear,

Fall, gall themselves, and gash gold-vermilion.

The poet is awestruck. At the moment of the bird’s beauty, the bird becomes more than itself and is revealed in its Christed nature. It stirs his heart. Even below in the plowed fields there shines in the dirt a gold-vermillion through a seemingly ordinary nature. In other words, the Incarnationalism is so strong that for Hopkins, he is not just being pointed to Christ, but the flight of the falcon or the overturned dirt in that moment is actually mediating Christ. In the impossible to define world of the poetic, we are somewhere between a metaphor and sacrament. Compare this with St. Ignatius, who writes, “I will consider how God dwells in creatures, in the elements…” Hopkins further points us in this direction when, later in his life, he writes that “my life is determined by the Incarnation down to most of the details of the day.”

We’ve just read through a number of sources that show the development of Hopkins on beauty as his life progresses. We should take careful note of the fact that his early aestheticism as learned at Oxford is not channeled into service of the Church of England’s undoubtedly gorgeous liturgy as an Anglican priest. This is a future that he actively rejects. No, Hopkins’s conception of beauty runs much deeper than an appealing veneer. We can trace the maturation of his thought as his poetry develops. He is not a romantic. Rather, his poetry is unprocessed, wild, and primeval. It is focused not on feelings or individuality, but on wording Christ. The kenosis of the Son into matter is the heart of all beauty and it is only in Christ that beauty is to be found and it is to Christ that beauty leads.

Now we can circle back again and reexamine the conversion to Catholicism. We have an idea of how Hopkins is thinking about beauty, the seed of his thought, so we can ask another question. What beauty does the Catholic faith have that Hopkins denies to the Church of England?

Simple:

The Real Presence.

In The Half-way House, he writes:

My national old Egyptian reed gave way:

I took of vine a cross-barred rod or rood.

Then next I hungered: Love when here, they say,

Or once or never took Love’s proper food;

But I must yield the chase, or rest and eat.-

Peace and food cheered me where four rough ways meet.

The “national old Egyptian reed” is a reference to the Church of England, which he finds giving way as he stands at a crossroads. At the intersection he finds life is suffering and life is pain. He is slowly starving for want of proper food. Life is either meaningless agony or it is the redemption of the Cross. Having examined his old faith, Hopkins finds that it lacks the one thing he needs. It has beautiful worship but it lacks Beauty. Beauty is only found in the Real Presence of Christ immolated on the altar; true food for the hungry.

The Eucharist is Hopkins’s answer to “Why Catholicism?” It is also his answer to “Where Beauty?” Both are perfected by the “better beauty,/ grace.”

No comments:

Post a Comment