History of Palm Sunday

by Fr. Francis X. Weiser

As soon as the Church obtained her freedom in the fourth century, the faithful in Jerusalem re-enacted the solemn entry of Christ into their city on the Sunday before Easter, holding a procession in which they carried branches and sang the Hosanna (Matthew 21, 1-11). In the early Latin Church, people attending Mass on this Sunday would hold aloft twigs of olives, which were not, however, blessed in those days.

This Palm Sunday procession, and the blessing of palms, seems to have originated in the Frankish Kingdom. The earliest mention of these ceremonies is found in the Sacramentary of the Abbey of Bobbio in northern Italy (beginning of the eighth century). The rite was soon accepted in Rome and incorporated into the liturgy. The prayers used today are of Roman origin. A Mass was celebrated in some church outside the walls of Rome, and there the palms were blessed. Then a solemn procession moved into the city to the basilica of the Lateran or to Saint Peter's, where the Pope sang a second Mass. The first Mass, however, was soon discontinued, and in its place only the ceremony of blessing was performed. Even today the ritual of the blessing clearly follows the structure of a Mass up to the Sanctus.

Everywhere in medieval times, following the Roman custom, a procession composed of the clergy and laity carrying palms moved from a chapel or shrine outside the town, where the palms were blessed, to the cathedral or main church. Our Lord was represented in the procession, either by the Blessed Sacrament or by a crucifix, adorned with flowers, carried by the celebrant of the Mass. Later, in the Middle Ages, a quaint custom arose of drawing a wooden statue of Christ sitting on a donkey (the whole image on wheels) in the center of the procession. These statues (Palm Donkey; Palmesel) are still seen in museums of many European cities.

As the procession approached the city gate, a boys' choir stationed high above the doorway would greet the Lord with the Latin song, Gloria, laus et honor. This hymn, which is still used today in the liturgy of Palm Sunday, was written by the Benedictine Theodulph, Bishop of Orleans (821):

Glory, praise and honor,

O Christ, our Savior-King,

To thee in glad Hosannas

Inspired children sing.

After this song, there followed a dramatic salutation before the Blessed Sacrament or the image of Christ. Both clergy and laity knelt and bowed in prayer, arising to spread cloths and carpets on the ground, throwing flowers and branches in the path of the procession. The bells of the churches pealed, and the crowds sang the Hosanna as the colorful procession entered the cathedral for the solemn Mass.

In medieval times this dramatic celebration was restricted more and more to a procession around the church. The crucifix in the church yard was festively decorated with flowers. There the procession came to a halt. While the clergy sang the hymns and antiphons, the congregation dispersed among the tombs, each family kneeling at the grave of relatives. The celebrant sprinkled holy water over the graveyard, the procession formed again and entered the church. In France and England they still retain the custom of decorating graves and visiting the cemeteries on Palm Sunday.

The inspiring rites and ceremonies of ancient times have long since disappeared, only the sacred texts of the liturgy are still preserved. Today the blessing of palms and the procession (if any) are performed within the churches preceding the Mass. In America, Catholic, and some Episcopal, churches distribute palms to all the congregation.

The various names for the Sunday before Easter come from the plants used--palms (Palm Sunday) or branches in general (Branch Sunday; Domingo de Ramos; Dimanche des Rameaux). In most countries of Europe real palms are unobtainable, so in their place people use many other plants: olive branches (in Italy), box, yew, spruce, willows, and pussy willows. In fact, some plants have come to be called palms because of this usage, as the yew in Ireland, the willow in England (palm-willow) and in Germany (Palmkatzchen). From the use of willow branches Palm Sunday was called Willow Sunday in parts of England and Poland, and in Lithuania Verbu Sekmadienis (Willow-twig Sunday). The Greek Church uses the names Sunday of the Palm-carrying and Hosanna Sunday.

Centuries ago it was customary to bless not only branches but also various flowers of the season (the flowers are still mentioned in the antiphons after the prayer of blessing).[35] Hence the name Flower Sunday which the day bore in many countries—Flowering Sunday or Blossom Sunday in England, Blumensonntag in Germany, Pasques Fleuris in France, Pascua Florida in Spain, Viragvasarnap in Hungary, Cvetna among the Slavic nations, Zaghkasart in Armenia.

The term Pascua Florida, which in Spain originally meant just Palm Sunday, was later also applied to the whole festive season of Easter Week. Thus the State of Florida received its name when, on March 27, 1513 (Easter Sunday), Ponce de Leon first sighted the land and named it in honor of the great feast.

In central Europe, large clusters of such plants, interwoven with flowers and adorned with ribbons, are fastened to the top of a wooden stick. All sizes of such palm bouquets may be seen, from the small children's bush to rods of ten feet and more. The regular palm, however, consists in most European countries of pussy willows bearing their catkin blossoms. In the Latin countries and in the United States, palm leaves are often shaped and woven into little crosses and other symbolic designs. This custom was originated by a suggestion in the ceremonial book for bishops, that little crosses of palm be attached to the boughs wherever true palms are not available in sufficient quantity.

This item 105 digitally provided courtesy of CatholicCulture.org

vexilla regis prodeunt

PALM SUNDAY & HOLY WEEK

by Dom Prosper Gueranger OSB

As we have already observed, there are three objects which principally engage the thoughts of the Church during Lent. The Passion of our Redeemer, which we have felt to be coming nearer to us each week; the preparation of the catechumens for Baptism, which is to be administered to them on Easter eve; the reconciliation of the public penitents, who are to be readmitted into the Church on the Thursday, the day of the Last Supper. Each of these three object engages more and more the attention of the Church, the nearer she approaches the time of their celebration.

The miracle performed by our Saviour almost at the very gates of Jerusalem, by which He restored Lazarus to life, has roused the fury of His enemies to the highest pitch of phrensy. The people’s enthusiasm has been excited by seeing him, who had been four days in the grave, walking in the streets of their city. They ask each other if the Messias, when He comes, can work greater wonders than these done by Jesus, and whether they ought not at once to receive this Jesus as the Messias, and sing their Hosanna to Him, for He is the Son of David. They cannot contain their feelings: Jesus enters Jerusalem, and they welcome Him as their King. The high priests and princes of the people are alarmed at this demonstration of feeling; they have no time to lose; they are resolved to destroy Jesus. We are going to assist at their impious conspiracy: the Blood of the just Man is to be sold, and the price put on it is thirty silver pieces. The divine Victim, betrayed by one of His disciples, is to be judged, condemned, and crucified. Every circumstance of this awful tragedy is to be put before us by the liturgy, not merely in words, but with all the expressiveness of a sublime ceremonial.

The catechumens have but a few more days to wait for the fount that is to give them life. Each day their instruction becomes fuller; the figures of the old Law are being explained to them; and very little now remains for them to learn with regard to the mysteries of salvation. The Symbol of faith is soon to be delivered to them. Initiated into the glories and the humiliations of the Redeemer, they will await with the faithful the moment of His glorious Resurrection; and we shall accompany them with our prayers and hymns at that solemn hour, when, leaving the defilements of sin in the life-giving waters of the font, they shall come forth pure and radiant with innocence, be enriched with the gifts of the holy Spirit, and be fed with the divine flesh of the Lamb that liveth for ever.

The reconciliation of the penitents, too, is close at hand. Clothed in sackcloth and ashes, they are continuing their work of expiation. The Church has still several passages from the sacred Scriptures to read to them, which, like those we have already heard during the last few weeks, will breathe consolation and refreshment to their souls. The near approach of the day when the Lamb is to be slain increases their hope, for they know that the Blood of this Lamb is of infinite worth, and can take away the sins of the whole world. Before the day of Jesus’ Resurrection, they will have recovered their lost innocence; their pardon will come in time to enable them, like the penitent prodigal, to join in the great Banquet of that Thursday, when Jesus will say to His guests: ‘With desire have I desired to eat this Pasch with you before I suffer.’ [St. Luke xxii. 15.]

Such are the sublime subjects which are about to be brought before us: but, at the same time, we shall see our holy mother the Church mourning, like a disconsolate widow, and sad beyond all human grief. Hitherto she has been weeping over the sins of her children; now she bewails the death of her divine Spouse. The joyous Alleluia has long since been hushed in her canticles; she is now going to suppress another expression, which seems too glad for a time like the present. Partially, at first [Unless it be the feast of a saint, as frequently happens during the first of these two weeks. The same exception is to be made in what follows.], but entirely during the last three days, she is about to deny herself the use of that formula, which is so dear to her: Glory be to the Father, and to the Son, and to the Holy Ghost. There is an accent of jubilation in these words, which would ill suit her grief and the mournfulness of the rest of her chants.

Her lessons, for the night Office, are taken from Jeremias, the prophet of lamentation above all others. The colour of her vestments is the one she had on when she assembled us at the commencement of Lent to sprinkle us with ashes; but when the dreaded day of Good Friday comes, purple would not sufficiently express the depth of her grief; she will clothe herself in black, as men do when mourning the death of a fellow-mortal; for Jesus, her Spouse, is to be put to death on that day: the sins of mankind and the rigours of the divine justice are then to weigh him down, and in all the realities of a last agony, He is to yield up His Soul to His Father.

The presentiment of that awful hour leads the afflicted mother to veil the image of her Jesus: the cross is hidden from the eyes of the faithful. The statues of the saints, too, are covered; for it is but just that, if the glory of the Master be eclipsed, the servant should not appear. The interpreters of the liturgy tell us that this ceremony of veiling the crucifix during Passiontide, expresses the humiliation to which our Saviour subjected Himself, of hiding Himself when the Jews threatened to stone Him, as is related in the Gospel of Passion Sunday. The Church begins this solemn rite with the Vespers of the Saturday before Passion Sunday. Thus it is that, in those years when the feast of our Lady’s Annunciation falls in Passion-week, the statue of Mary, the Mother of God, remains veiled, even on that very day when the Archangel greets her as being full of grace, and blessed among women.

PALM SUNDAY

by Dom Prosper Gueranger

Early in the morning of this day, Jesus sets out for Jerusalem, leaving Mary His Mother, and the two sisters Martha and Mary Magdalene, and Lazarus, at Bethania. The Mother of sorrows trembles at seeing her Son thus expose Himself to danger, for His enemies are bent upon His destruction; but it is not death, it is triumph, that Jesus is to receive today in Jerusalem. The Messias, before being nailed to the gross, is to be proclaimed King by the people of the great city; the little children are to make her streets echo with their to the Son of David; and this in presence of the soldiers of Rome's emperor, and of the high priests and pharisees: the first standing under the banner of their eagles; the second, dumb with rage.

The prophet Zachary had foretold this triumph which the Son of Man was to receive a few days before His Passion, and which had been prepared for Him from all eternity. 'Rejoice greatly, O daughter of Sion! Shout for joy, O daughter of Jerusalem! Behold thy fling will come to thee; the Just and the Saviour. He is poor, and riding upon an ass, and upon a colt, the foal of an ass.'[1] Jesus, knowing that the hour has come for the fulfilment of this prophecy, singles out two from the rest of His disciples, and bids them lead to Him an ass and her colt, which they would find not far off. He has reached Bethphage, on Mount Olivet. The two disciples lose no time in executing the order given them by their divine Master; and the ass and the colt are soon brought to the place where He stands.

The holy fathers have explained to us the mystery of these two animals. The ass represents the Jewish people, which had been long under the yoke of the Law; the colt, upon which, as the evangelist says, no man yet hath sat.[2] is a figure of the Gentile world, which no one had ever yet brought into subjection. The future of these two peoples is to be decided a few days hence: the Jews will be rejected, for having refused to acknowledge Jesus as the Messias; the Gentiles will take their place, to be adopted as God's people, and become docile and faithful.

The disciples spread their garments upon the colt; and our Saviour, that the prophetic figure might be fulfilled, sits upon him,[3] and advances towards Jerusalem. As soon as it is known that Jesus is near the city, the holy Spirit works in the hearts of those Jews, who have come from all parts to celebrate the feast of the Passover. They go out to meet our Lord, holding palm branches in their hands, and fondly proclaiming Him to be King.[4] They that have accompanied Jesus from Bethania, join the enthusiastic crowd. Whilst some spread their garments on the way, others out down boughs from the palm-trees, and strew them along the road. Hosanna is the triumphant cry, proclaiming to the whole city that Jesus, the Son of David, has made His entrance as her King.

Thus did God, in His power over men's hearts, procure a triumph for His Son, and in the very city which, a few days later, was to glamour for His Blood. This day was one of glory to our Jesus, and the holy Church would have us renew, each year, the memory of this triumph of the Man-God. Shortly after the birth of our Emmanuel, we saw the Magi coming from the extreme east, and looking in Jerusalem for the King of the Jews, to whom they intended offering their gifts and their adorations: but it is Jerusalem herself that now goes forth to meet this King. Each of these events is an acknowledgment of the kingship of Jesus; the first, from the Gentiles; the second, from the Jews. Both were to pay Him this regal homage, before He suffered His Passion. The inscription to be put upon the gross, by Pilate's order, will express the kingly character of the Crucified: Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews. Pilate, the Roman governor, the pagan, the base coward, has been unwittingly the fulfiller of a prophecy; and when the enemies of Jesus insist on the inscription being altered, Pilate will not deign to give them any answer but this: 'What I have written, I have written.' Today, it is the Jews themselves that proclaim Jesus to be their King: they will soon be dispersed, in punishment for their revolt against the Son of David; but Jesus is King, and will be so for ever. Thus were literally verified the words spoken by the Archangel to Mary when he announced to her the glories of the Child that was to be born of her: 'The Lord God shall give unto Him the throng of David, His father; and He shall reign in the house of Jacob for ever.'[5] Jesus begins His reign upon the earth this very day; and though the first Israel is soon to disclaim His rule, a new Israel, formed from the faithful few of the old, shall rise up in every nation of the earth, and become the kingdom of Christ, a kingdom such as no mere earthly monarch ever coveted in his wildest fancies of ambition.

This is the glorious mystery which ushers in the great week, the week of dolours. Holy Church would have us give this momentary consolation to our heart, and hail our Jesus as our King. She has so arranged the service of today, that it should express both joy and sorrow; joy, by uniting herself with the loyal of the city of David; and sorrow, by compassionating the Passion of her divine Spouse. The whole function is divided into three parts, which we will now proceed to explain.

The first is the blessing of the palms; and we may have an idea of its importance from the solemnity used by the Church in this saved rite. One would suppose that the holy Sacrifice has begun, and is going to be offered up in honour of Jesus' entry into Jerusalem. Introit, Collect, Epistle, Gradual, Gospel, even a Preface, are said, as though we were, as usual, preparing for the immolation of the spotless Lamb; but, after the triple the Church suspends these sacrificial formulas, and turns to the blessing of the palms. The prayers she uses for this blessing are eloquent and full of instruction and, together with the sprinkling with holy water and the incensation, impart a virtue to these branches which elevates them to the supernatural order, and makes them means for the sanctification of our souls and the protection of our persons and dwellings. The faithful should hold these palms in their hands during the procession, and during the reading of the Passion at Mass, and keep them in their homes as an outward expression of their faith, and as a pledge of God's watchful love.

It is scarcely necessary to tell our reader that the palms or olive branches, thus blessed, are carried in memory of those wherewith the people of Jerusalem strewed the road, as our Saviour made His triumphant entry; but a word on the antiquity of our ceremony will not be superfluous. It began very early in the east. It is probable that, as far as Jerusalem itself is concerned, the custom was estate. fished immediately after the ages of persecution St. Cyril, who was bishop of that city in the fourth century, tells us that the palm-tree, from which the people out the branches when they went out to meet our Saviour, was still to be seen in the vale of Cedron.[6] Such a circumstance would naturally suggest an annual commemoration of the great event. In the following century, we find this ceremony established, not only in the churches of the east, but also in the monasteries of Egypt and Syria. At the beginning of Lent, many of the holy monks obtained permission from their abbots to retire into the desert, that they might spend the saved season in strict seclusion; but they were obliged to return to their monasteries for Palm Sunday, as we learn from the life of Saint Euthymius, written by his disciple Cyril.[7] In the west, the introduction of this ceremony was more gradual; the first trace we find of it is in the sacramentary of St. Gregory, that is, at the end of the sixth, or the beginning of the seventh, century. When the faith had penetrated into the north, it was not possible to have palms or olive branches; they were supplied by branches from other trees. The beautiful prayers used in the blessing, and based on the mysteries expressed by the palm and olive trees, are still employed in the blessing of our willow, box, or other branches; and rightly, for these represent the symbolical ones which nature has denied us.

The second of today's ceremonies is the procession, which comes immediately after the blessing of the palms. It represents our Saviour's journey to Jerusalem, and His entry into the city. To make it the more expressive, the branches that have just been blessed are held in the hand during it. With the Jews, to hold a branch in one's hand was a sign of joy. The divine law had sanctioned this practice, as we read in the following passage from Leviticus, where God commands :His people to keep the feast of tabernacles: And you shall take to you, on the first day, the fruits of the fairest tree, and branches of palm-trees, and boughs of thick trees, and willows of the brook, and you shall rejoice before the Lord your God.[8] It was, therefore, to testify their delight at seeing Jesus enter within their walls, that the inhabitants, even the little children, of Jerusalem, went forth to meet Him with palms in their hands. Let us, also, go before our King, singing our to Him as the conqueror of death, and the liberator of His people.

During the middle ages, it was the custom, in many churches, to carry the book of the holy Gospels in this procession. The Gospel contains the words of Jesus Christ, and was considered to represent Him. The procession halted at an appointed place, or station: the deacon then opened the sacred volume, and sang from it the passage which describes our Lord's entry into Jerusalem. This done, the cross which, up to this moment, was veiled, was uncovered; each of the clergy advanced towards it, venerated it, and placed at its foot a small portion of the palm he held in his hand. The procession then returned, preceded by the gross, which was left unveiled until all had re-entered the church. In England and Normandy, as far back as the eleventh century, there was practised a holy ceremony which represented, even more vividly than the one we have just been describing, the scene that was witnessed on this day at Jerusalem: the blessed Sacrament was carried in procession. The heresy of Berengarius, against the real presence of Jesus in the Eucharist, had been broached about that time; and the tribute of triumphant joy here shown to the sacred Host was a distant preparation for the feast and procession which were to be instituted at a later period.

A touching ceremony was also practised in Jerusalem during today's procession, and, like those just mentioned, was intended to commemorate the event related by the Gospel. The whole community of the Franciscans (to whose keeping the holy places are entrusted) went in the morning to Bethphage. There, the father guardian of the holy Land, being vested in pontifical robes, mounted upon an ass, on which garments were laid. Accompanied by the friars and the Catholics of Jerusalem, all holding palms in their hands, he entered the city, and alighted at the church of the holy sepulchre where Mass was celebrated with all possible solemnity.

We have mentioned these different usages, as we have done others on similar occasions, in order to aid the faithful to the better understanding of the several mysteries of the liturgy. In the present instance, they will learn that, in today's procession, the Church wishes us to honour Jesus Christ as though He were really among us, and were receiving the humble tribute of our loyalty. Let us lovingly go forth to meet this our King, our Saviour, who comes to visit the daughter of Sion, as the prophet has just told us. He is in our midst; it is to Him that we pay honour with our palms: let us give Him our hearts too. He comes that He may be our King; let us welcome Him as such, and fervently cry out to Him: Hosanna to the Son of David!'

At the close of the procession a ceremony takes place, which is full of the sublimes" symbolism. On returning to the church, the doors are found to be shut. The triumphant procession is stopped; but the songs of joy are continued. A hymn in honour of Christ our King is sung with its joyous chorus; and at length the subdeacon strikes the door with the staff of the gross; the door opens, and the people, preceded by the clergy, enter the church, proclaiming the praise of Him, who is our resurrection and our life.

This ceremony is intended to represent the entry of Jesus into that Jerusalem of which the earthly one was but the figure-the Jerusalem of heaven, which has been opened for us by our Saviour. The sin of our first parents had shut it against us; but Jesus, the King of glory, opened its gates by His cross, to which every resistance yields. Let us, then, continue to follow in the footsteps of the Son of David, for He is also the Son of God, and He invites us to share His kingdom with Him. Thus, by the procession, which is commemorative of what happened on this day, the Church raises up our thoughts to the glorious mystery of the Ascension, whereby heaven was made the close of Jesus' mission on earth. Alas! the interval between these two triumphs of our Redeemer are not all days of joy; and no sooner is our procession over, than the Church, who had laid aside for a moment the weight of her grief, falls back into sorrow and mourning.

The third part of today's service is the offering of the holy Sacrifice. The portions that are sung by the choir are expressive of the deepest desolation; and the history of our Lord's Passion, which is now to be read by anticipation, gives to the rest of the day that character of saved gloom, which we all know so well. For the last five or six centuries, the Church has adopted a special chant for this narrative of the holy Gospel. The historian, or the evangelist, relates the events in a tone that is at once grave and pathetic; the words of our Saviour are sung to a solemn yet sweet melody, which strikingly contrasts with the high dominant of the several other interlocutors and the Jewish populace. During the singing of the Passion, the faithful should hold their palms in their hands, and, by this emblem of triumph, protest against the insults offered to Jesus by His enemies. As we listen to each humiliation and suffering, all of which were endured out of love for us, let us offer Him our palm as to our dearest Lord and King. When should we be more adoring, than when He is most suffering?

Palm Sunday by R. Barron

These are the leading features of this great day.

Commentary on St Mark's Passion

What happened on the Cross?

How does Mark see Christ's Death?

HOMILY OF ABBOT PAUL, 2018

Christus factus est pro nobis

“Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest.” We are struck on Palm Sunday by the stark contrast between the joyful exuberance of the blessing of palms with its procession and the bleak reality of the Mass that follows, centred as it is on the Passion. That first Holy Week, the disciples were unprepared for what was to follow on from the triumphal entry into Jerusalem. They hadn’t really understood the words of Jesus that he would suffer and die so as to enter fully into his glory. The same crowds, who welcomed him into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, would soon be screaming out, “Crucify him! Crucify him!” Some would mock him saying, “He saved others, he cannot save himself,” little realising the truth concealed in their words, for on the cross Jesus didn’t need to save himself but he did save everyone else.

St Mark’s Gospel, short and succinct as it is, contains a highly developed theology of the cross. More than Matthew, Luke or John, he emphasizes the abandonment of Jesus and how he faced his arrest, trial, condemnation, crucifixion and death alone. At Gethsemane his disciples can’t fathom his fear and distress or understand the meaning of his words, “My soul is sorrowful to the point of death.” They fall asleep as he prays not to be put to the test, for “the spirit is willing but the flesh is weak.” He is already alone, even while Peter, James and John are still with him. He goes on to die in total isolation and, after his death, it’s a centurion, a gentile, not one of the disciples, who acknowledges who he is, when he confesses, “Truly, this man was a son of God.” Only the women are there, but at a distance, frightened and confused.

The glory of Jesus was to suffer and die for us, for our forgiveness and salvation. St Paul tells the Philippians that from the moment of his death on the cross, “all beings in the heavens, on earth and in the underworld, should bend the knee at the name of Jesus and every tongue proclaim that Jesus Christ is Lord, to the glory of God the Father.” Christ’s Death and Resurrection are a great comfort to all who see in Jesus the image of the unseen God. In Christ’s Passion we derive great consolation as we find our own cross hard to bear. It wasn’t easy for Jesus: it’s clear from St Mark’s Passion narrative that he experienced human vulnerability, distress, fear, agitation and grief, even to the point of death. He begged the Father that this hour might pass him by and the cup of suffering be taken from him. He was indeed, “a man like us in all things but sin.”

Contemplating Our Lord’s Passion and Crucifixion this week, let us thank him for his sacrifice of love that sets us free to love God and our neighbour. We pray that we too may give our lives in sacrifice, not thinking of ourselves and of our own needs, but putting others first. Let us thank him for showing us the meaning of the mystery of life, that, by patiently taking up our own cross every day and following him, we may come to share in the glory of his Resurrection as we now share in his suffering and death. Amen.

Christus factus est pro nobis

(Bruckner)

HH Pope Benedict XVI

in Westminster Cathedral

CELEBRATION OF PALM SUNDAY OF THE PASSION OF THE LORD

HOMILY OF POPE FRANCIS

St. Peter's Square

29th World Youth Day

Sunday, 13 April 2014

This week begins with the festive procession with olive branches: the entire populace welcomes Jesus. The children and young people sing , praising Jesus.

But this week continues in the mystery of Jesus’ death and his resurrection. We have just listened to the Passion of our Lord. We might well ask ourselves just one question: Who am I? Who am I, before my Lord? Who am I, before Jesus who enters Jerusalem amid the enthusiasm of the crowd? Am I ready to express my joy, to praise him? Or do I stand back? Who am I, before the suffering Jesus?

We have just heard many, many names. The group of leaders, some priests, the Pharisees, the teachers of the law, who had decided to kill Jesus. They were waiting for the chance to arrest him. Am I like one of them?

We have also heard another name: Judas. Thirty pieces of silver. Am I like Judas? We have heard other names too: the disciples who understand nothing, who fell asleep while the Lord was suffering. Has my life fallen asleep? Or am I like the disciples, who did not realize what it was to betray Jesus? Or like that other disciple, who wanted to settle everything with a sword? Am I like them? Am I like Judas, who feigns loved and then kisses the Master in order to hand him over, to betray him? Am I a traitor? Am I like those people in power who hastily summon a tribunal and seek false witnesses: am I like them? And when I do these things, if I do them, do I think that in this way I am saving the people?

Am I like Pilate? When I see that the situation is difficult, do I wash my hands and dodge my responsibility, allowing people to be condemned – or condemning them myself?

Am I like that crowd which was not sure whether they were at a religious meeting, a trial or a circus, and then chose Barabbas? For them it was all the same: it was more entertaining to humiliate Jesus.

Am I like the soldiers who strike the Lord, spit on him, insult him, who find entertainment in humiliating him?

Am I like the Cyrenean, who was returning from work, weary, yet was good enough to help the Lord carry his cross?

Am I like those who walked by the cross and mocked Jesus: “He was so courageous! Let him come down from the cross and then we will believe in him!”. Mocking Jesus….

Am I like those fearless women, and like the mother of Jesus, who were there, and who suffered in silence?

Am I like Joseph, the hidden disciple, who lovingly carries the body of Jesus to give it burial?

Am I like the two Marys, who remained at the Tomb, weeping and praying?

Am I like those leaders who went the next day to Pilate and said, “Look, this man said that he was going to rise again. We cannot let another fraud take place!”, and who block life, who block the tomb, in order to maintain doctrine, lest life come forth?

Where is my heart? Which of these persons am I like? May this question remain with us throughout the entire week.

© Copyright - Libreria Editrice Vaticana

Pope Palm Sunday Mass: Sing out loud "Hosanna"! 2018

By Sr Bernadette Mary Reis, fspReflecting on the Liturgy of Palm Sunday, Pope Francis contrasted the joy of the people who celebrated Jesus’ entry into Jerusalem with the cries of those who want to silence him.

Pope Francis invites us all to see ourselves in the Palm Sunday liturgy. He says that the liturgy “expresses the contradictory feelings that we too, … experience”: love and hatred, self-sacrifice and “washing our hands”, loyalty and betrayal.

Pope Francis Palm Sunday and Angelus of 25 March 2018

Sounds of joy

The Pope says that we can imagine that among those in the crowd who sang and shouted as Jesus entered Jerusalem would have been such people as the prodigal son, the healed leper, “those who had followed Jesus because they felt his compassion for their pain and misery.” Their “outcry is the song and the spontaneous joy of all those left behind and overlooked, who, having been touched by Jesus, can now shout: ‘Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord.’ ” These people cannot but help to praise the person responsible for restoring their dignity and their hope, making it possible for them to trust again, the Pope says.

Joy suppressed

But there is another group present as well. The joy of those who have been touched by God’s mercy is unbearable and intolerable for others Pope Francis points out. “How hard it is for the comfortable and the self-righteous to understand the joy and the celebration of God’s mercy!”

This prompts another kind of shouting, Pope Francis observes. It comes from those wishing to “twist reality,” “invent stories,” “gain power,” “silence dissonant voices,” “spin facts,” defend themselves, and discredit the defenseless. In the end, “they disfigure the face of Jesus and turn him into a ‘criminal,’ ” Pope Francis says.

“And so the celebration of the people ends up being stifled. Hope is demolished, dreams are killed, joy is suppressed; the heart is shielded and charity grows cold.”

The joy of the young

The conclusion of Pope Francis’ homily was directed to the young. He pleaded with them not to succumb to the attempts of their elders to silence them.

“Dear young people, the joy that Jesus awakens in you is a source of anger and irritation to some, since a joyful young person is hard to manipulate,” he says.

Pope Francis recalls the words of Jesus to the Pharisees who wanted to silence his disciples. To “Teacher, rebuke your disciples,” Jesus replied, “I tell you, if these were silent, the very stones would cry out” (Lk 19:39-40).

Pope Francis begs young people to choose to sing Hosanna and not to keep quiet: “Please, make that choice, before the stones themselves cry out.”

EASTERN 5TH SUNDAY OF LENT

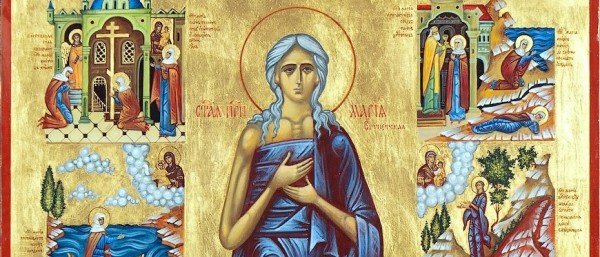

It is not possible to establish with any certainty what part history and what part legend play in the traditions that relate to St Mary of Egypt. One may as well admit the fact that the Church wished to make her, as we sing in matins, "a pattern of repentance". She is a symbol of conversion, of contrition, and of austerity. On this last Sunday of Lent, she expresses the last and most urgent call that the Church addresses to us before the sacred days of the Passion and the Resurrection.

The epistle read at the liturgy (Heb.9. 11-14) compares the ministry of Christ to that of the High Priest of the Jews. Once, each year, he entered into the Tabernacle, but Christ "entered only once into the holy place, having obtained eternal redemption for us". The High Priest purified and sanctified the faithful by sprinkling them with the blood and ashes of sacrificed animals. "How much more shall the blood of Christ, who through the eternal Spirit offered himself without spot to God, purge your conscience from dead works to serve the living God"

The Gospel (Mark 10, 32-45) describes Jesus's ascent to Jerusalem before his Passion. Jesus takes the twelve apostles aside and starts to tell them that he will be betrayed, condemned and put to death, and that he will rise again from the dead. At the threshold of Holy Week could we be "taken aside" by the Saviour for a talk in which he explains to us, personally, the mystery of Redemption? Do we ask the Master to help us understand at greater depth what is taking place for our sakes on Golgotha? Do we make it possible for Jesus to meet us in secret? Do we seize opportunities to be alone and quiet with the Lord? Then the sons of Zebedee come to Jesus and ask him to let them sit with him in his glory, one on his right and the other on his left. Jesus asks them - and puts the same question to us: "Can you drink of the cup that I drink of?" The Master then explains to his disciples that true glory lies in serving others. For "the son of man came not to be ministered unto but to minister, and to give his life as a ransom for many."

Already the evening of this last Sunday in Lent allows a glimmer of the light of Holy Week, the following Sunday, to shine in it. Next Saturday will be the Saturday of Lazarus, whom Jesus will raise from the dead; and vespers which are celebrated in the evening of the fifth Sunday of Lent, by alluding to Lazarus, the begger in the Gospel parable, announce Lazarus who was raised from the dead.

"Grant me to be with the poor man Lazarus, and deliver me from the punishment of the rich man...allow us to rival his endurance and long-suffering."

The Church, as if somehow impatient to enter the very holy days which begin the following week, urge us, on the last Sunday of Lent, to anticipate the feast which we will celebrate in seven days:

Let us sing a hymn in preparation for the feast of Palms, to the Lord who comes with glory to Jerusalem in the power of the Godhead, that he may slay death...Let us prepare the branches of victory crying, "Hosannah to the Creator of all."

The Year of Grace of the Lord

by a monk of the Eastern Church

St Vladimir's Seminary Press

ISBN 0-13836-68-0

Commemoration of St Mary of Egypt

On the final Sunday of Great Lent in the Orthodox Church we remember St. Mary of Egypt and her great example of repentance.

“Then she (St. Mary of Egypt) turned to Zosima and said: ‘Why did you wish, Abba Zosima, to see a sinful woman? What do you wish to hear or learn from me, you who have not shrunk from such great struggles?’ Zosima threw himself on the ground and asked for her blessing. She likewise bowed down before him. And thus they lay on the ground prostrate asking for each other's blessing. And one word alone could be heard from both: ‘Bless me!’ After a long while the woman said to Zosima: ‘Abba Zosima, it is you who must give blessing and pray. You are dignified by the order of priesthood and for many years you have been standing before the holy altar and offering the sacrifice of the Divine Mysteries.’ This flung Zosima into even greater terror. At length with tears he said to her: ‘O mother, filled with the spirit, by your mode of life it is evident that you live with God and have died to the world. The grace granted to you is apparent -- for you have called me by name and recognized that I am a priest, though you have never seen me before. Grace is recognized not by one's orders, but by gifts of the Spirit, so give me your blessing for God's sake, for I need your prayers.’ Then giving way before the wish of the elder the woman said: ‘Blessed is God Who cares for the salvation of men and their souls.’" (The Life of St. Mary of Egypt, attributed to Sophronius of Jerusalem)

Among the many not-very “pc” moments in the Life of St. Mary of Egypt, read in our churches at matins of the fifth Thursday of Lent, the one quoted above caught my attention this year. Zosima, who is a priest-monk, is asking for, nay, begging for “with tears,” the blessing of a woman. (She made “a grown man cry,” in fact, – so even the Rolling Stones would be impressed, I’m thinking, rather irrelevantly, and probably irreverently). Zosima notes that “grace is recognized not by one’s orders, but by gifts of the Spirit.”

From all this I can glean a basic lesson about the openness of the Holy Spirit to all of us, regardless of our gender, or “order,” or anything else, when we open ourselves to participating in His grace. All of us can, indeed, be blessed, and also impart “blessing” (“ev-logia” in Greek, meaning “a good word”) onto our world and those we encounter, when we choose to embrace God’s “good” Word, the eternal “Logos” and our Lord, Jesus Christ, – rather than “other” words and narratives of reality, like the voices in our own heads or other sources of merely-human opinion.

So let me be blessed this morning, by re-connecting with God’s Spirit in some heartfelt prayer, that I may bless, throughout my schedule today. Holy Mother Maria, pray to God for us!

St Mary of Egypt by Sister Vassa

(Happy Thursday, dear zillions! Please NOTE, you can get these reflections daily via EMAIL, simply by typing in your email-address at our website. So just do it: www.coffeewithsistervassa.com)

No comments:

Post a Comment