ST AUGUSTINE AND THE ROLE OF HUMILITY

THE HUMILITY OF GOD MEETS AND TRANSFORMS THE HUMILITY OF THE CHRISTIAN

my source: from a very rich article: The Humble God , Healer,Mediator and Sacrificeby Deborah Wallace Ruddy. I advise yo to read the whole article.

Augustine understood humility as a distinctly Christian attribute. It was inconceivable to him that humility could be valued apart from a belief in the Incarnation. In reference to the various moral systems of his day, Augustine writes, “Everywhere are to be found excellent precepts concerning morals and discipline, but this humility is not to

be found. This way of humility comes from another source; it comes from Christ. . . . What else did he teach but this humility?”4 In other words, only through the grace of believing in this divine descent could we appreciate humility as central to human perfection. In the Confessions, Augustine explains that Christian love begins and builds

on the “foundation of humility which is Christ Jesus.”5 All other Christian virtues are built on and sustained by this foundational Christian attribute that grows out of God’s self-disclosure in Jesus Christ.6 To know Jesus is to know his humility, for he is the archetype and master of humility (magister humilitatis).7 What is so singular about Augustine’s teaching on humility is that he so clearly views Christ’s humility as more than a moral example to be imitated; it is the central way that our reconciliation with God occurs. Christ’s humility is both salvific and exemplary.8 It is the way and the truth. Augustine’s distinctive contribution to the topic of humility, then, is his direct linking of humility to soteriology:

On every side the humility of the good master is being assiduously impressed upon us, seeing that our very salvation in Christ consists in the humility of Christ. There would have been no salvation for us, after all, if Christ had not been prepared to humble himself for our sakes.9 Christ’s humility is a “saving humility.”10 Moveover, the way that God saves us is inseparable from salvation itself: “our very salvation in Christ consists in the humility of Christ.”

11 To understand better the salvific nature of humility, Augustine directs us to three fundamental aspects of Christ’s humility.

First, it is confrontational—stressing the contrast between humility and pride:

“Because pride has wounded us, humility makes us whole.”

Just as the source of spiritual blindness and bondage is human pride, so the source of spiritual sight and freedom is divine humility.

Second, it is mediatory—bridging the chasm that pride creates between humanity and God.

Third, and most important, it is kenotic. Here we see the full extent and cost of humility. The divine self-emptying begins with the Incarnation and extends to death on a cross.

Confrontational:

Since we had abandoned God through pride, it was impossible for us to return to him except through humility, and there was no one we could take as a model in this effort. Pride had corrupted the whole human race. And even if there were some men to be found who were humble in spirit, such as the prophets and patriarchs, mankind could not bring itself to imitate mere men, however humble. In order then that men might not disdain to imitate a humble man, God himself became humble; even human pride could not refuse to follow in the steps of God!15

Listen . . . in case you should be broken by despair; listen to how you have been loved when you weren’t in the least lovable, listen to how you were loved when you were foul, ugly, before there was anything in you worth loving. You were first loved, in order to become worth loving.18

So he is the doctor who in no way needs any such medicine; and yet to encourage the sick person he drinks what he had no need of himself, by way of coaxing him out of his refusal and easing his dread of the medicine; he drinks it first. The cup, he says, which I am to drink. There’s nothing in me that needs to be treated by that cup, but I’m going to drink it all the same, so that you won’t loftily refuse to drink it; and you certainly need to.

MEDIATOR BETWEEN GOD AND MANKIND

At the heart of Augustine’s understanding of Christ’s mediation is the joining of humanity to the divinity in Christ’s person:

“He has appeared as Mediator between God and men, in such ways as to join both natures in the unity of one Person, and has both raised the commonplace to the heights of the uncommon and brought down the uncommon to the commonplace.”28

This new bond between God and humanity is not a joining of equals—the ordinary becomes incorporated into the extraordinary, and through this mingling the ordinary takes on new meaning and possibility. The unity of Christ’s person heals and ennobles what has been wounded and disgraced. It is possible not only to be restored to right relationship with God and creation but also to share in the divine life itself, “O, happy fault.”

While Augustine maintains his antithetical style within his theology of mediation, it is similarity more than dissimilarity that is emphasized here. In The Trinity, Augustine writes,

“Just as the devil in his pride brought proud thinking man down to death, so Christ in his humility brought obedient man back to life.”29

As the devil mediates death, Christ mediates life.30 The devil’s pride is a rebellion against God; Christ’s humility is a submission to God. As the antidote

to pride, Christ’s humility works negatively through confrontation and contrast. But in the context of mediation, Christ’s humility works more positively, drawing the sinner closer throughsimilarity and kinship:

But when sin had placed a wide gulf between God and the human race, it was expedient that a Mediator, who alone of the human race was born, lived, and died without sin, should reconcile us to God, and procure even for our bodies a resurrection to eternal life, in order that the pride of man might be exposed and cured through the humility of God; that man might be shown how far he had departed from God, when God became incarnate to bring him back.31

Christ’s Humility as Kenosis:

Crux illa signum est humilitatis

Augustine, more directly than any other Church Father, credits St. Paul,“the least” of the apostles,50 as the source of his appreciation for Christ’s humility.51 St. Paul taught Augustine that the humility of the Incarnation52 is utterly distinct from the teachings and categories of Neoplatonism and other pagan philosophies.53 Sometime during his rereading of Paul’s letters , Augustine is struck in a new way by the humility of Christ’s self-emptying. As he reflects on the second chapter of Paul’s letter to the Philippians, in which Christ’s humbling is parallel to his emptying he highlights how Christ’s kenosis is essential to the meaning of humility.

In this humble act of self-emptying love, Christ reveals the very structure of our salvation. Out of humility, the Son who shares all the divine characteristics

with the Father takes on humanity.Without losing divinity, he comes to us in the form of a servant.

The Philippians hymn encapsulates the full scope of Christ’s humility, for it describes Christ’s two divine “humblings.” The first humbling is God becoming human—fully entering what is less and sharing earthly limitations. Not grasping at divinity or exploiting his power as God, the Word freely takes on the limits of the human condition.

Augustine stresses that this act of humility, in itself, is astounding. In this act of becoming human, the Word forms a new bond between God and humanity. But God’s self-abasement goes even further. The second humbling—Christ’s suffering and death -demonstrates the consummation of humility: “And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death—even death on a cross” Christ’s humble selfemptying extends to suffering the ridicule and abuse of his persecutors who nail him to a cross. The self-emptying that unfolds throughout Jesus’ life culminates in his being condemned and crucified by those he came to save. Without sin, and consequently unbound to the path of human mortality, Christ chose to take on the consequences of our sin. Augustine stresses that Christ’s humility is God’s initiative given in love and generosity for our sakes. He suffers freely and without coercion.

Augustine tries to understand why God chose to save humanity in such an extreme and costly way. He insists there is nothing haphazard, accidental, or even necessary about the cross. Christ deliberately chose to make himself accountable for our sin through his suffering and death. As God, he was fully in charge and did not need to suffer or die. His humility is pure sacrifice. Highlighting Christ’s free decision to accept the cross, Augustine writes,

“It would, after all, have been perfectly easy for him to come down from the cross.”55

But by choosing the lowly path, Christ ensures the victory of all subsequent

suffering patterned on Christ’s own suffering.

In the second part of Philippians , Christ is the recipient of the Father’s action of glorification. The receptive dimension of Christ’s humility is seen in his total openness before the Father who exalts him and gives him “the name that is above every name.”56 Here, Christ teaches us we cannot receive God’s Spirit unless we recognize

our need for God and freely choose to depend on God. As the eternal doer and receiver of the Father’s will, Christ models the agency and receptivity his followers are called to embody in their own lives.

Augustine explains that the second part of Paul’s pericope describes the depth of God’s love for us and the full extent of the Word’s self-emptying. Christ’s submission to humiliations, torture, and death demonstrates the full meaning of the first part of the hymn. His death is the completion of the kenosis that is first revealed in the Word made flesh.

[Paul] wouldn’t have defined the full measure of [Christ’s] humility yet, if he hadn’t added,death too on a cross ... he took upon himself, something peculiarly disgraceful, in order to provide a reward for those who are not ashamed of this thing,humility.57

The cross, then, is not merely an instrument to salvation; it is the precise way God chose to reveal himself and establish our own return to God.

According to the Philippians hymn, the Christian life reflects Christ’s self-offering and consists of a voluntary lowering, or abasement, followed by a “raising up,” or exaltation, to union with God.

The Word gives up exaltation for a time so we might be exalted with him. Christ does not seek his own glory but the glory of the Father, who exalts him above all.58 Christ’s descent into humanity and, ultimately, into the grave, becomes the road to ascent. Augustine explains that the foundation of this salvific pattern is humility:

“For from death comes resurrection, from resurrection ascension, from ascension the sitting at the Father’s right hand; therefore the whole process began in death, and the glorious splendor had its source in humility.”59

Benedictine Monasticism: Humility

The spiritual battle takes place within. This battle is one of returning to God, of turning back to the One whom we have abandoned through our sin. Thus, the battle takes the form of uprotting vice and developing virtue. This combat occurs on several fronts, which are traditionally divided into the world, the flesh, and the devil.

This combat is also against the seven capital sins: gluttony, lust, greed, anger, envy, sloth, and pride. Pride, the most insidious of these, in a certain sense encompasses all of the rest. Consequently, the whole conversion process hinges upon conquering pride. The antidote is the virtue of humility.

Humility is defined as "a quality by which a person considering his own defects has a humble opinion of himself and willingly submits himself to God and to others for the sake of God." To be humble is to know truly the relationship between oneself and God. When the perspective is focused, the utter dependence of the creature upon God becomes evident. God is to be adored. He is to be loved above all and the neighbor loved for His sake and in Him. The humble monk is able to love God perfectly. This view of humility is multi-faceted. It is like an entire arsenal to vanquish each vice, making room for every virtue. Our Holy Father Benedict teaches twelve steps of humility to his monks in the Holy Rule. St. Benedict teaches that a monk must

1. Always be aware of the presence of God2. Love not doing his own will but the will of God3. Submit to the Abbot in obedience4. Obey superiors even in hardship5. Confess his sins to a spiritual father6. Be content with his circumstances7. Believe in his heart that he is least of the brothers8. Follow the rule and tradition of the monastery9. Refrain from excessive speech10. Refrain from raucous laughter11. Speak as is appropriate in a monastery

12. Keep a humble bearing in his body

The reward of these steps of humility is to "come quickly to that love of God which in its fulness casts our all fear." To follow this path is to act with prudence, justice, temperance and fortitude. With these cardinal virtues in place, the monk can fulfill the will of God and be raised by grace to the heights of holiness.

Christ in his humanity is the greatest example of Humility. This truth is explicated in the grand hymn of Saint Paul:

"Though he was in the form of God, he did not regard equality with God as something to be exploited, but emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself and became obedient to the point of death – even death on a cross." (Philippians 2:6-8)

COMMENTARY ON CHAPTER 7

by Abbot Philip Lawrence, Christ in the Desert

Chapter 7, Verses 31-33

31 The second step of humility is that a man loves not his own will nor takes pleasure in the satisfaction of his desires; 32 rather he shall imitate by his actions that saying of the Lord: I have come not to do my own will, but the will of him who sent me (John 6:38). 33 Similarly we read, “Consent merits punishment; constraint wins a crown.”

Commentary by Philip Lawrence, OSB, Abbot of Christ in the Desert

The steps of humility go against so much that we value. Naturally, I love my own will and I take pleasure in the satisfaction of my desires. Thus, this road of humility that Saint Benedict maps out for us is clearly, from the beginning, a road that is not easy to travel. I am invited to become single-minded in seeking God’s will and doing God’s will. There have been many ways of saying this in the long Christian and monastic tradition.

We speak about “conforming my will to God’s will.” That is because we recognize that I cannot kill my own will. I must always remain responsible for my actions. Thus whenever I discover that God’s will is not my will, I seek to change my will and accept His will.

This is intimately tied up with not taking pleasure in the satisfaction of my own desires. It is a discipline for me to deny my own desires. I do this, not in some sadistic or masochistic way, but simply in the ordinary things of life. The purpose of such an activity is to free me, so that I can recognize that there are lots of things that I do that bind me. The whole challenge of the spiritual life is to become free IN ORDER TO DO GOD’S WILL.

Today, at the end of the 2nd millenium, we are so caught up trying to discover who we are and trying to be faithful to our inner spirit that it is difficult to recognize the call of the Gospel which indicates that we shall discover ourselves by denying ourselves for the sake of doing God’s will. For many, this makes no sense. For those who have discovered its inner dynamic, it seems almost self-evident. For the one following the monastic way, it is the only road.

Chapter 7, Verse 34

34 The third step of humility is that a man submits to his superior in all obedience for the love of God, imitating the Lord of whom the Apostle says: He became obedient even to death (Phil 2:8).

Commentary by Philip Lawrence, OSB, Abbot of Christ in the Desert

This degree of humility is always read to us on Good Friday, no matter what section of the Rule falls on that day. There have been many attempts to re-interpret this degree of humility, but it is really difficult to put any other interpretation on this: submit to the superior. There are some communities today where even the word “superior” is banished from the vocabulary. For Benedict, a superior is simply someone over us–not someone better than us, not someone who knows more than we do and for sure not necessary anyone more holy than we. The “superior” is simply another human being who is set over us. And we submit to the superior in obedience. Why? Because we want to die! This is no morbid desire, but simply the desire to die to ourselves so that we may live fully in Christ. Surely one of the quickest way to deep inner freedom is the mature choice to submit ourselves to another human being in obedience in all things except that which is sinful. Such obedience almost immediately opens a spiritual vista before us, showing that so much of what we hold important, even necessary, simply impedes spiritual growth. This is a tried and true road to living in Christ. It is a road that is often rejected today but which is a wonderful way to the Lord.

Chapter 7, Verses 35-43

35 The fourth step of humility is that in this obedience under difficult, unfavourable, or even unjust conditions, his heart quietly embraces suffering 36 and endures it without weakening or seeking escape. For Scripture has it: Anyone who perseveres to the end will be saved (Matt 10:22), 37 and again, Be brave of heart and rely on the Lord (Ps 26[27]:14). 38 Another passage shows how the faithful must endure everything, even contradiction, for the Lord’s sake, saying in the person of those who suffer, For your sake we are put to death continually; we are regarded as sheep marked for slaughter (Rom 8:36; Ps 43[44]:22). 39 They are so confident in their expectation of reward from God that they continue joyfully and say, But in all this we overcome because of him who so greatly loved us (Rom 8:37). 40 Elsewhere Scripture says: God, you have tested us, you have tried us as silver is tried by fire; you have led us into a snare, you have placed afflictions on our backs (Ps 65[66]:10-11). 41 Then, to show that we ought to be under a superior, it adds: You have placed men over our heads (Ps 65[66]:12).

42 In truth, those who are patient amid hardships and unjust treatment are fulfilling the Lord’s command: When struck on one cheek, they turn the other; when deprived of their coat, they offer their cloak also; when pressed into service for one mile, they go two (Matt 5:39-41). 43 With the Apostle Paul, they bear with false brothers, endure persecution, and bless those who curse them (2 Cor 11:26; 1 Cor 4:12).

Commentary by Philip Lawrence, OSB, Abbot of Christ in the Desert

This step of humility gives some details or developments of the steps two and three. Today we are taught to resist injustice. We must stand up for our rights. We must protest. How far different is this attitude of the Holy Rule. There is surely no problem is stating that injustice is injustice. Benedict is not asking us to embrace immorality of any type. Yet we are invited to endure injustice with a quiet heart and embrace the suffering that it brings–for the sake of serving the Lord.

Again, we must say immediately that there are many who reject this teaching or who want to spiritualize it so that there is no sting to it. But in the sting comes the spiritual growth. In verse 41 Benedict is clearly stating that the one who follows the monastic way will suffer from the “superior.” Clearly Benedict expects this and believes that spiritual growth will come through it.

Today there is huge emphasis on community, on leadership, on consensus and all the nice qualities that work so well in a perfect community. Benedict seems not to expect that kind of community at all. Consensus for Benedict lies in following the decision of the superior, even when the superior is stubborn, contradictory and stupid. It is interesting to see the contrast between the form of community so often advocated today and that of the Holy Rule. There is no doubt that Benedict wants the superior of the community to listen to the members; Benedict wants the superior to strive to make good decisions. The real challenge is when the superior does not do that or does it in a way that goes against me.

Am I willing to accept this challenge? Can I embrace this monastic road that leads to Christ? Will I let myself be put down so that Christ may triumph in me?

Chapter 7, Verses 44-47

44 The fifth step of humility is that a man does not conceal from his abbot any sinful thoughts entering his heart, or any wrongs committed in secret, but rather confesses them humbly. 45 Concerning this, Scripture exhorts us: Make known your way to the Lord and hope in him (Ps 36[37]:5). 46 And again: Confess to the Lord, for he is good; his mercy is forever (Ps 105[106]:1; Ps 117[118]:1). 47 So too the Prophet: To you I have acknowledged my offence; my faults I have not concealed. 48 I have said: Against myself I will report my faults to the Lord, and you have forgiven the wickedness of my heart (Ps 31 [32]:5).

Commentary by Philip Lawrence, OSB, Abbot of Christ in the Desert

Now, to add insult to injury, Benedict asks the monk to reveal any sinful thoughts that enter his heart to the abbot! We can ask ourselves: Isn’t it bad enough to have to admit the mistakes that I make that are all too obvious to everyone? Do I really have to reveal even the thoughts that come to me which I work to hard to conceal?

We come up against this question again: Do I want to follow this monastic path? Nobody is forcing me to do so. It is an invitation of the Lord. There are many today who follow the monastic way but who will not follow this path! We can certainly find lots of literature tell us that this is not the way to go.

I do not think that this is one of those things that monastic tradition has proven to be unworkable, such as the Abbot always eating with the guests. Rather, this is one of those things in the spiritual tradition that really demands a deep humility and most of us are simply scared to try this path. This path is not demanded of me, but the invitation is clearly there if I take the steps of humility seriously.

Chapter 7, Verses 49-50

49 The sixth step of humility is that a monk is content with the lowest and most menial treatment, and regards himself as a poor and worthless workman in whatever task he is given, 50 saying to himself with the Prophet: I am insignificant and ignorant, no better than a beast before you, yet I am with you always (Ps 72[73]:22-23).

Commentary by Philip Lawrence, OSB, Abbot of Christ in the Desert

If we have accepted the first steps of humility, this one is a cinch! If we have worked hard to do steps two, three, four and five, this sixth step will hardly delay us at all. We find this manner of living even among non-Christians who are seeking a spiritual path. What I do is not really important. How I do it makes all the difference in the world. Surely we have all felt the sting of being thought less capable that we think we are. Can we embrace that evaluation with peace and even with joy. It is not a matter of fooling others. We are not invited to think: “Oh, yes, I am undervalued and I shall offer it to Christ!” No, it is a matter of deeply believing that others evaluation of me are really not important and that I can do whatever I am asked to do–with great joy and gladness. This is not low self-esteem, but rather a simple recognition of who I am before the Lord. My value comes from the Lord. My life comes from the Lord. I give it back to the Lord without any fanfare.

Chapter 7, Verses 51-54

51 The seventh step of humility is that a man not only admits with his tongue but is also convinced in his heart that he is inferior to all and of less value, 52 humbling himself and saying with the Prophet: I am truly a worm, not a man, scorned by men and despised by the people (Ps 21[22]:7). 53 I was exalted, then I was humbled and overwhelmed with confusion (Ps 87[88]:16). 54 And again: It is a blessing that you have humbled me so that I can learn your commandments (Ps 118[119]:71,73).

Commentary by Philip Lawrence, OSB, Abbot of Christ in the Desert

Living this step of humility is impossible if we are looking at anything other than God. If we look at God and all else only in God, then we see only God in everything and yet still know our own weaknesses and failures. The weaknesses and failures of others no longer concern us or distract us–for we were never able to judge them anyway. Our own weaknesses and failures–there we do know the motivations and the lack of choosing God. We can truly say that we are inferior and of less value than all else. The purpose of this humility is to learn God’s ways, God’s commandments.

Chapter 7 Verse 55

55 The eighth step of humility is that a monk does only what is endorsed by the common rule of the monastery and the example set by his superiors.

Commentary by Philip Lawrence, OSB, Abbot of Christ in the Desert

This step of humility goes against my desire to be different from others. So often I want to do that which is different simply to assert my own identity. What this step of humility is telling me is that I must find my identity from within, from within Christ, not from what I do. One Abbot said: “Follow the good example of the seniors, not their bad example.” What a delight it is in a Monastery when we encounter young monks who simply want to do what is right and what is best and understand the meaning of this degree of humility intuitively.

56 The ninth step of humility is that a monk controls his tongue and remains silent, not speaking unless asked a question, 57 for Scripture warns, In a flood of words you will not avoid sinning (Prov 10:19), 58 and, a talkative man goes about aimlessly on earth (Ps 139[140]:12).

Commentary by Philip Lawrence, OSB, Abbot of Christ in the Desert

This step of humility trains us in patience, that wonderful virtue that helps us suffer for the sake of growth. For anyone: try to practice for one day not speaking unless someone asks you a question! What a learning experience this is! All of us can benefit from the discipline of this step of humility. How many words we use each day that are not really necessary. How often we use talk to distract ourselves.

Chapter 7, Verse 59

59 The tenth step of humility is that he is not given to ready laughter, for it is written: Only a fool raises his voice in laughter (Sir 21:23).

Commentary by Philip Lawrence, OSB, Abbot of Christ in the Desert

This step is very much like the previous step, but now we struggle against our own laughter. There is a laughter that delights in the Lord and in others. Too often, however, our laughter comes from other realities within us. How often do I laugh from nervousness? Do I laugh at times simply because others are laughing–and sometimes the laughter hurts others or makes light of something that should be taken seriously? How much do I know about my own laughter–its causes and its effects?

Chapter 7, Verses 60 and 61

60 The eleventh step of humility is that a monk speaks gently and without laughter, seriously and with becoming modesty, briefly and reasonably, but without raising his voice, 61 as it is written: “A wise man is known by his few words.”

Commentary by Philip Lawrence, OSB, Abbot of Christ in the Desert

If we have worked on the 9th and the 10th steps, this one is the combination of the fruits of the previous two. Silence can teach us to speak gently. Gentleness always helps others hear us. We know–all of us–that if we go to a person and start a conversation with insulting words, generally we will not be heard. Often just the tone of voice opens or closes our capacity of truly hearing the other person. Thus Benedict would have us speak with gentleness. And how many of us know people who take a half hour to say what could have been said in two minutes! What about ourselves? Can we strive to be modest, brief and reasonable in our speech? Does that really ask too much of us?

Chapter 7, Verses 64-66

62 The twelfth step of humility is that a monk always manifests humility in his bearing no less than in his heart, so that it is evident 63 at the Work of God, in the oratory, the monastery or the garden, on a journey or in the field, or anywhere else. Whether he sits, walks or stands, his head must be bowed and his eyes cast down. 64 Judging himself always guilty on account of his sins, he should consider that he is already at the fearful judgment, 65 and constantly say in his heart what the publican in the Gospel said with downcast eyes: Lord, I am a sinner, not worthy to look up to heaven (Luke 18:13). 66 And with the Prophet: I am bowed down and humbled in every way (Ps 37[38]:7-9; Ps 118[119]:107).

Commentary by Philip Lawrence, OSB, Abbot of Christ in the Desert

Today, when there is so much emphasis on “integration,” this aspect of humility should be understand easily. The interior attitude should be visible in the external deportment. There are people with very poor self-image who always have their heads bowed down and their eyes downcast–but this is obviously not true humility. The person who is humble has a true sense of self-worth. This person knows that God is always present and is centered in that reality, rather than in self. The truly humble person knows when to look up and when to look down, when to bow the head and when to lift the head, when to look and when to cast the gaze down.

Chapter 4, Verses 67-70

67 Now, therefore, after ascending all these steps of humility, the monk will quickly arrive at that perfect love of God which casts out fear (I John 4:18). 68 Through this love, all that he once performed with dread, he will now begin to observe without effort, as though naturally, from habit, 69 no longer out of fear of hell, but out of love for Christ, good habit and delight in virtue. 70 All this the Lord will by the Holy Spirit graciously manifest in his workman now cleansed of vice and sins.

Commentary by Philip Lawrence, OSB, Abbot of Christ in the Desert

At last we come to a quiet time in life. Surely it does come, even in the spiritual life. The monastic men and women of the desert said to beware of such times, because they can be illusion. Quiet time does not mean that there is no struggle, but life is certainly much easier. There are three things that characterize the monastic person at this level of integration: acting from the love of Christ, from good habit and from delight in virtue. Once in a great while we find this in young people in the monastery, generally we hope to find it in those who have lived the life for a number of years.

"DESCENT AS A WAY OF MEETING GOD"

Conversations with Abba Isaac: Spiritual Neurosis

by Fr Micah Hirschy

About a month ago, returning from a funeral in northern Alabama, I decided to turn on the radio. Driving down a very rural country road, I began to listen to a local broadcast where people would call in and speak with the host/Pastor of the show about the Bible. I am not sure which verse or verses were being discussed, but what struck me was the story of a gentleman who called in and the subsequent conversation he had with the host.

The gentleman related to the host how shortly after becoming a Christian, he suffered from severe anxiety and depression, being filled with an inner turmoil about whether or not he was one of the “saved”. It was only after years of therapy that he was able to “work through things”. The host’s response was not of surprise, but rather, he accepted this man’s story as one he had heard seemingly countless times before.

At the time, I was quite shocked by the story and response, and found it disturbing that a seemingly normal and balanced individual would, upon becoming religious, undergo what he himself characterized as a breakdown.

As I thought about this, it occurred to me that there is a certain spiritual neurosis that religious people often develop and that this is indeed nothing new and something that we Orthodox are not immune to. Our beloved Father and contemporary, Saint Porphyrios, speaks on this topic at some length:

For many people, however, religion is struggle, a source of agony and anxiety. That’s why many of the ‘religious minded’ are regarded as unfortunates, because others can see the desperate state they are in. And so it is. Because for the person who doesn’t understand the deeper meaning of religion and doesn’t experience it, religion ends up as an illness, and indeed a terrible illness. So terrible that the person becomes weak willed and spineless… They make prostrations and cross themselves in Church and they say, ‘we are unworthy sinners’, then as soon as they come out they start to blaspheme everything holy whenever someone upsets them a little.

St. Porphyrios goes on to say that the healing and transfiguring power of our Christian faith has a “most important precondition” and that precondition is humility.

It was precisely for this reason that the great luminary of the desert and our Father among the Saints, Abba Isaac, over a thousand years ago recognized that any and every religious activity without humility is nothing and worse than nothing. He tells us, “Humility, even without works, gains forgiveness for many offenses; but without her, works are of no profit to us and instead prepare for us great evils.”

According to Abba Isaac, humility is the way to authentic life, balance, and both wholeness and holiness. “A humble man is never rushed, hasty, or agitated, never has any hot or volatile thoughts, but at all times remains calm. Even if the heavens were to fall upon the earth, the humble man would not be dismayed.”

He teaches that humility is a gift from God. However, we can and must prepare ourselves and strive to become worthy of such an exalted gift. This is done through a “precise knowledge of one’s sins or as a result of recognizing the lowliness of our Lord – or rather, as a result of recollecting the greatness of God and the extent to which the greatness of the Lord lowered itself…”

Abba Isaac raises the lowliness of the humble man to such heights that he says, “Rightly directed labors and humility make man a god upon earth.” We must remember that our ascent to God upon the ladder of humility is deifying because our Lord descended to us upon the ladder of humility – or rather, He has Himself become for us the ladder of humility uniting us to God.

For humility is the clothing of the Godhead. The Word who became man clothed Himself in it…Every man who has been clothed in it has truly been made like unto Him who came down from His own exaltedness, and hid the splendor of His majesty… less creation be utterly consumed by the contemplation of Him.

THE LADDER OF DIVINE ASCENT AND MORAL IMPROVEMENT

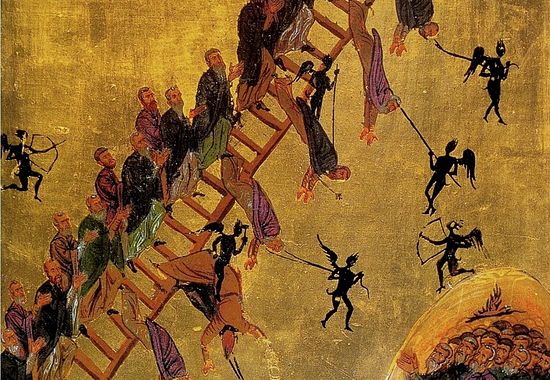

The Fourth Sunday of Great Lent in the Orthodox Church, is dedicated to St. John Climacus, the author of the ancient work, The Ladder of Divine Ascent. It is a classic work describing “steps” within the life of the struggling ascetic. There is an icon associated with this work, picturing monastics climbing the rungs of a ladder to heaven, battling demons who are trying to pull them off. However, ladders are dangerous things to put in the hands of a modern Christian.

Modernity likes ladders. We like the idea of upward mobility, of continuing improvement, of moral progress. We speak of “career ladders” and the “ladder of success.” It is the myth of personal power. Modernity is a cultural phenomenon created by the theology of the Reformation and the philosophy of the Enlightenment. Freed from the constraints of inherited tradition (such as the Catholic Church) and the royal state (hurrah for democracy), modernity is a story told to individuals that they can now become whatever they want. Freedom and personal industry are the twin rails supporting the rungs of progress. As a philosophy, this idea and its associated notions are the bedrock of free-market capitalism. As theology, it is the foundation for self-help Christianity and the positive, motivational preaching of contemporary religion. “Be all that you can be, and Jesus can help!”

Nurtured in this culture, contemporary Orthodox believers are not immune to its allure, particularly if the images appear in the guise of desert monasticism and Byzantine/Russian-style striving. More than once I have heard the sad confession, “I don’t feel like I’m a very good Orthodox Christian.” Implied in this statement is that Orthodox Christians should, somehow, be better than other Christians. Some foolish people even call us the “marines” of the spiritual life.

Of course, all of this, particularly when applied to writings such as St. John’s Ladder, is pure distortion and delusion. Its most subtle and seductive version is that of moral progress. I wrote a series of articles last year denouncing the concept of moral progress, identifying it as largely a modern notion and not consistent with the mind of the fathers. Here, I reaffirm that without equivocation.

We simply are not saved by getting better. It is a false image and a false goal. Of course, critics will charge that I’m being defeatist and suggesting a path devoid of moral effort. I am doing nothing of the sort. Everyone should, at all times, struggle against sin. But measuring, even watching for improvement can be not only self-defeating but sinful in itself. The Ladder points to a very different path:

“You cannot escape shame except by shame,” St. John says (4.62).

We do not gradually improve and thereby leave our shame behind us. The way down is the way up. The ladder of divine ascent is actually a ladder of divine descent. The path to union with God is only found in making the descent with Him. “Lo, if I descend into hell, Thou art there” (Ps 139:8). St. Gregory the Theologian says, “If He descends into hell, go with Him” (Oration 45).

The path of modernity carries no humility. It breeds pride, and frequently contempt. Failure is its nemesis. We blame ourselves for laziness and sloth, certain that a little more effort will make the difference. Like a child given a bad grade, we plead that we’ll try harder. Confession is seen as the Second Chance, the opportunity to pull up our grades. “Loser!” is the taunt of the modern world (a word spawned in the pit of hell).

But St. John points us towards our shame. He does not describe a path of moral improvement. His path follows the Cross, which is the descent into Hades. My failure, not sought for its own sake (we do not sin in order to gain grace), is always and immediately the gate of Hades and the gate of Paradise. When I acknowledge my failure and refuse to hide from its shame, we can call out for Christ to comfort us. “I did not turn my face from the shame and the spitting” (Is. 50:6). He will meet us in our shame, and takes it upon Himself. My failure becomes the failure of God (2 Cor. 5:21). It does not separate me from Christ, but, ironically, unites me to Him in the paradox that is at the very heart of our salvation. God became what we are, that we might become what He is. God does not meet us in the middle. He meets us at the bottom and asks us to meet Him there as well.

It is within that place that true humility is born. Judgment ceases. If I accept my shame in union with Christ, how can I judge another? Indeed, it is largely my efforts to avoid my shame that makes me judge my brother. We can only avoid judging if we “see our own transgressions” (as we are taught in the Prayer of St. Ephrem).

Modernity loves excellence. The moral improvement pitches of the motivational preachers love the drive for excellence. Our bosses and the owners demand that we strive for excellence. God is not our boss, nor does He place us in His debt (“freely you have received”). The constant nagging voice demanding improvement and excellence is not the voice of God. It is often nothing more than the neurotic echo of modernity sounding in our brains. It drives us with the threat of shame. However, Christ has trampled down shame by shame and invites us to do the same thing. “You cannot escape shame except by shame.”

Become a Christian who follows Christ. We do not seek to please Him with our excellence. We seek to imitate Him by going where He has gone.

Requiem Mass

for Dom Antony Tumelty O.S.B.

PAX

Of your charity pray for the repose of the soul of

Dom Antony Tumelty

who died on 27th August 2017,

in his 64th year,

fortified by the Rites of Holy Church.

He had been professed 43 years

and ordained 37 years.

7th September 2017

Fr Antony has asked me not to say anything about him this afternoon, but rather to speak only about God, his infinite love and mercy and the precious gift of life, his own life, which he has shared with us through the Incarnation of his Divine Son, Our Lord and Saviour Jesus Christ, and his Sacrifice on the Cross, in which we are united to him through the Sacraments and in our own personal suffering, which must always be seen in the light of Our Lord’s Passion and Death. He asked me to tell you, his beloved community, family and friends, to focus on God and worship him alone, for nothing else matters. He wanted no attention whatever drawn to himself, but asked us simply to pray for the repose of his soul. St Paul wrote to the Philippians, “You have been granted the privilege not only to believe in Christ but also to suffer for his sake.” (Ph. 1:29) May we see in our own sufferings, whatever they may be, a privileged participation in the sufferings of Christ, the Sacrifice of the Eternal High Priest.

In today’s second reading, we heard St Paul say, “The sufferings of this present time are not worthy to be compared with the glory which shall be revealed in us.” (Rm. 8:18) Our faith teaches us that Christ has opened the gates of Heaven to those who believe and take up their cross every day and follow him. Nevertheless, despite our good intentions and many prayers, we are all conscious of our failings and sinfulness. As we grow older and prepare for death, we are even more aware of our need for God’s mercy and forgiveness. St Benedict tells his monks in the Holy Rule that we should always keep death before our eyes. As Catholics we firmly believe in the reality and truth of Purgatory and of the need to pray for the dead. Indeed, that is the very purpose of a Requiem Mass and of our many Mass intentions. Purgatory is not a place of punishment but of purification; it is the antechamber or narthex, you could say, that leads up to the gates of Heaven and “the glory which shall be revealed in us.”

It is the duty of every Christian to pray for the souls in Purgatory, the Church Expectant, especially the souls that have been forgotten and have no one to pray for them. It is the greatest act of charity. In Purgatory the souls of the faithful departed are filled with joyful hope as their sins are washed away and their burdens lifted. There their wedding garments are restored to their pristine beauty in anticipation of the heavenly Bridegroom’s call, inviting them to enter the Banquet of the Lamb, “Come, you blessed of my Father, inherit the Kingdom prepared for you from the foundation of the world.” (Matt. 25:34) This is Fr Antony’s final word and testament to us all.

Requiem aeternam dona ei, Domine, et lux perpetua luceat ei. Requiescat in pace. Amen.

No comments:

Post a Comment