TWO MOVEMENTS: ONE SPIRIT

The monastic movement sprang up in the early Church as though from nowhere in Egypt and Syria where, from the earliest days, the Judeo-Christian influence was particularly strong and the links between church and synagogue lasted longer than in other places. In Syria, their first language was a form of Aramaic, while in Persian Syria, their theology was strongly Semitic. The Hellenistic Judaism of Alexandria was responsible for the translation of the Hebrew Bible into the Septuagint, was famous for its intellectual life as true centre of Hellenistic Judaism. The famous Jewish thinker Philo taught the allegorical interpretation of Scripture which was inherited by the Alexandrian school of Christian theology. On the other hand, this was opposed by the rabbinic theology of the pharisees whose basic position on Scripture was inherited by the Antiochene school of theology, along with Antioch's opposition to Alexandria. Nevertheless, for all their opposition to each other, the monastic movement has its roots in both traditions.

The Charismatic Movement is also one without any clear human founder. With its roots in the Protestant sects Revival with the Methodist Holiness Movement of the 18th and 19th centuries among the afro poor and the marginalised whites, forming pentecostal sects.

It began to spread into the mainline Protestant churches. Then, in 1968, it hit the Catholic Church that had become all too cerebral and theoretical since Vatican II at the expense of devotion.

Here is a good account of how it became Catholic:

Here is a good account of how it became Catholic:

In my experience, there is much imagination at work in the Catholic Charismatic Renewal: there are people who imagine they are having a profound encounter with the Spirit; people who imagine they are exercising the gift of healing and those who imagine they are being healed; those who imagine that the Spirit speaks through them etc. There are people also who are quite bonkers or who disguise their egocentricity in charismatic clothes. However, the same can be said about monastic life: imagination can cause people to think they are holier than they are.

Yet, I have met real growth in holiness, real humility, profound prayer and clear indications of the Holy Spirit at work. I have heard and taken part in singing in tongues in which the sound was stunningly beautiful,moving to a climax and descending harmoniously into a deep silence: each voice was doing its own thing, without any conducter, but the general impression was like a Russian Orthodox Liturgy.

For almost seven years, I was parish priest of a charismatic renewal parish in northern Peru, and I met the Renewal at its worst and the Renewal at its best; and I had no doubt that it is a school of authentic Catholic holiness, often as imagination was transformed into reality.

Neverthless, I believe it would be greatly improved and matured as a Catholic movement if it were to go out of its way to learn from the other great charismatic movement in Catholic history.

- It should learn and emphasise the importance of humility in anyone who wishes to act as an instrument of the Holy Spirit in the community: many are humble, but it is not sufficiently taught.

- There are two ways that a person might exercise charisms, a) simply allowing the Spirit to act through you in ways discerned by the community; or, as Fr Tom Hopko tells us, as we receive the gift of the Person of the Spirit, we allow him more and more, to act in synergy with us as persons, without mixing, or separation, with Him enabling us and we, in ever deeper humble obedience, allowing Him to act. Thus we have the charismatic activity of St John Mary Vianney, St Seraphim of Sarov or Padre Pio. It is the way of the saints. The Charismatic Renewal needs Elders with experience to whom others willingly obey. The importance of humble obedience and training in it.

- The importance of silent, one-to-one, prayer. The Jesus prayer fits into the Charismatic spirituality very well.

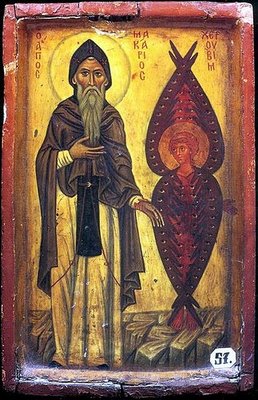

St. Macarius the Great: Clothed with the Holy Spirit

St. Marcarius the Great was truly a saint chosen by God from a very young age, perhaps even from his birth. He was born in the village of Shabsheer-Menuf, in the province of Giza south of Cairo, from good and righteous parents. His story is reflective of another found in the Holy Bible. His parents were Abraham and Sarah and they had no son. In a dream an angel of God told Abraham that he would have a son and his name would be known all over the earth. This son would be further blessed with a multitude of spiritual sons.

When Abraham's son was born, he was named "Marcarius" which means blessed. He was an obedient son in all things. At his parent's insistence and against his will he was forced into marriage. Feigning an illness, he asked to be allowed to go into the wilderness to seek a speedy recovery. While in the wilderness Marcarius prayed to the Lord Jesus Christ to be directed to do what was pleasing unto Him. His humbleness gave him the strength to be obedient in all things despite his personal desires.

While in the desert Marcarius had a vision in which he saw a beautiful winged Cherubim who took him to a high mountaintop. While at the height of the mountain, Marcarius was told, "God has given the desert to you and your spiritual sons for an inheritance." He was shown the vast expanse of the desert to the east and west, north and south. Following this he returned from the wilderness home to find that his virgin wife had departed. Although respective of the departure, Marcarius was now happy to lead the life in which he so ardently desired.

Shortly thereafter, his parents also departed and he gave all that they had left to the poor. At about the age of 30, he began his life of asceticism in a cell near his village. The people of the village admired his humbleness and purity and took him to the Bishop of Ashmoun who ordained Marcarius as a priest for them. Father Marcarius had not wished to become a priest. In his humility he could not refuse.

A certain young girl in the village became pregnant and accused Father Macarius of fathering her unborn child. The people without weighing the matter immediately sought him out and brought him back to the village. They beat and whipped Father Marcarius severely and hung huge black pots around his neck. He was forced to go before the village while they were mocking him and saying, "This monk seduced our daughter. Let him be hanged." With the merciless behavior shown to him he continued in humility.

When allowed to return to his cell, he gave a young man all the mats that he had made from the work of his hands. Father Marcarius instructed the young man to "Sell these mats and give the money to MY WIFE that she may eat." Father Macarius in thought had accepted this young woman as his wife without a single denial or bitter thought. He worked night and day making mats to send money to her. Humbleness was the mother of forgiveness in this saints soul.

At the time of the young girl's delivery, she suffered many days in labor. The unbearable pain motivated the girl into telling the truth regarding Father Macarius. She related to all that she had falsely accused this priest and that he had never so much as touched her. Having not been able to deliver until she confessed, the entire village was remorseful at their judgmental actions. When Father Macarius heard that the village was on route to seek his forgiveness he fled to the place where he would live the remainder of his holy life. His humble and forgiving natures were the clothes in which he would wear throughout his life.

This is how he came to the Desert of Scetis in the Valley of Nitron. He is known to have visited St. Anthony to seek his spiritual guidance in beginning his life in the desert. The prophecy foretold to him by his lifetime companion the cherub was about to be fulfilled. Many monks joined Father Marcarius in the desert, filling the wilderness with prayers and fasting. Countless cells and caves were filled with these men who desired to be in continual worship to the Lord Jesus Christ.

It is said that he dwelt in the Inner Desert, in the place of the Monastery of Sts Maximus and Domadius, which is now known as the Monastery of El-Baramous. As the monasteries rose in number this dry desert begin to flower and became known as "The Paradise of the Holy Fathers".

One day while meditating St. Macarius thought that perhaps there were no more righteous people in the world. A voice came from Heaven and said "In the City of Alexandria you will find two very righteous women." He took his staff and went to the city. He was guided to the home of the two women where he inquired of their life. One of them related to him, "There is no kinship between us and when we married these two brothers we asked them to leave us to be nuns but they refused. So we committed ourselves to spend our life fasting until evening and we pray diligently. When each of us had a son, whenever one of them would cry, any one of us would carry and nurse him even if he was not her own son. We are in one living arrangement, the unity of opinion is our model, and our husbands work as shepherds, we are poor and only have our daily bread and what is left over we give to the poor and needy." Rejoicing he bade them farewell. Reflecting upon the comfort of the Holy Spirit to all those who loved the Lord his soul was filled with compassion once again and he returned to his beloved desert.

Father Marcarius is known for his humble encounters with those whom followed him into the desert way of life. There was a certain monk who was leading other monks astray in his proclaiming that there was no resurrection of the dead. The bishop of the City of Osseem went to Father Marcarius and told him about the saying of this particular monk. Father Marcarius went and stayed with the erring monk until the monk returned to the correct and true beliefs concerning the resurrection of the dead.

As the abbot of his monastery, Abba Marcarius dealt with many problems and always solved them in a humbled manner. It was reported to him through the monks of the monastery that a particular monk had allowed a woman to enter his cell. Abba Macarius did not reprimand nor scold this monk. The monks continued to wait for the woman's return. Upon discovering her presence once again they reported their finding to Abba Macarius.

He entered the monk's cell and asked the others to wait outside. Upon hearing the approaching footsteps of others, the brother had hidden the women in a big trunk used for storing grain. When Abba Macarius entered he promptly sat upon the trunk knowing its hidden contents. He called the other monks to enter. They did not see the women in question and dared not to ask Abba Macarius the contents of the trunk he was sitting upon. When the others had left, Abba Macarius looked at the brother in question and said, "Brother, judge yourself before they judge you, because the true judgment comes only from God." As did our Lord and Savior, Abba Macarius concealed other people's sins.

As was the birth of this humble saint so is his departure date. The twenty-seventh day of the Blessed Month of Baramhat is also the Commemoration of the Crucifixion of the Lord Jesus Christ. I am sure this humble saint considers it with solemn humility to have his departure date overshadowed by the Commemoration of the Crucifixion. With the Holy Crucifixion foremost in everyone's mind, the Lord our God allowed Abba Macarius the Great's life to remain "clothed in humility" for all generations and all the years to come.

His "clothing in humility" led him to be remembered as "Epnevma-Tovoros" meaning "clothed WITH the Holy Spirit". "Blessed are the poor in spirit for theirs is the Kingdom of God" (Matthew 5:3)

May we keep the humbleness of Abba Macarius and his total dependence upon God ever before us and may this great saint's blessings be with us all.

H.G. Bishop Youssef

Bishop, Coptic Orthodox Diocese of the Southern United States

Introduction to Precious Vessels of the Holy Spirit

The Lives & Counsels of Contemporary Elders of Greece

The Ancient Christian Ministry of Spiritual Eldership:

It is not uncommon, among both non-Orthodox as well as Orthodox, in the west (and increasingly even among Orthodox in traditionally "Orthodox" countries), for the ancient tradition of spiritual eldership to be either completely unknown or misunderstood. The central role, however, that the relation of elder to spiritual child has played in the life of the Church throughout Christian history attests to its legitimacy. Similarly, the existence of living links to this Christian tradition, inherited from one generation to the next, even to the present day, attests to its vitality.

Although an academic exposition of the historical roots of eldership falls outside the scope of the present work, we do feel it necessary to look at these roots in general outline so as to place the present work in its proper context.[1] This outline necessarily begins with the New Testament witness, which may then be traced historically to the present day, and to the Greek monastic elders in this book.

Spiritual eldership, preserved by the Holy Spirit from apostolic times, descends to us in much the same way as does apostolic succession (understood as the historical succession of bishops from apostolic times until the present). As Bishop Kallistos Ware explains:

Alongside this [apostolic succession], largely hidden, existing on a 'charismatic' rather than an official level, there is secondly the apostolic succession of the spiritual fathers and mothers in each generation of the Church—the succession of the saints, stretching from the apostolic age to our own day, which Saint Symeon the New Theologian termed the "golden chain."... Both types of succession are essential for the true functioning of the Body of Christ, and it is through their interaction that the life of the Church on earth is accomplished. [2]

The foundation on which the spiritual tradition of eldership is based is found in Holy Scripture. In particular, Christ's Incarnation, Death and Resurrection, reveal His kenotic [3] Fatherly love for His children and for the world. This love has as its goal the ontological rebirth of man from within, not the ethical improvement of man (although this is an inevitable fruit of true spiritual rebirth) from without. [4] Faithfully following Christ's example, St. Paul gives us a clear picture of what the relationship of elder to spiritual child means in practical terms. His relationship to the churches he founded is not simply the relationship of teacher to disciple, "For though ye have ten thousand instructors in Christ, yet have ye not many fathers: for in Christ Jesus I have begotten you through the gospel. Wherefore I beseech you, be ye followers of me." (I Corinthians 4:15-16). St. Paul's birth imagery is significant here, as the relationship of mother to child is transposed onto the spiritual plane. His words also indicate the completely free nature of this relationship: full of love for his spiritual children, and selflessly interested in their spiritual well being, he beseeches them to follow his example. [5] In his letter to the Galatians, St. Paul uses similar imagery, "My little children, of whom I travail in birth again until Christ be formed in you." (Galatians 4:19). As becomes clear from these passages, St. Paul does not see his role as that of a simple teacher who teaches people and then leaves them to their own devices, nor as a psychologist, who tries to provide psychological answers to spiritual questions. He accepts responsibility for his children, identifying himself with them, "Who is weak, and I am not weak? Who is offended, and my heart is not ablaze with indignation?" (2 Corinthians 11:29). Bishop Kallistos develops this point a bit further, "He helps his children in Christ precisely because he is willing to share himself with them, identifying his own life with theirs. All this is true also of the spiritual father at a later date. Dostoevsky's description of the starets may be applied exactly to the ministry of Saint Paul: like the elder, the apostle is one who 'takes your soul and your will into his soul and will.'" [6] It is significant here, furthermore, that the elder does not assert his own will upon the spiritual child. On the contrary, he accepts the spiritual child as he is, receiving the child's soul into his own soul. This most basic aspect of this spiritual relationship points to one of the reasons that this ancient ministry is so uncommon, especially today.

The ability the elder has to, "take your soul and your will into his soul and will," is a fruit of his own willingness to empty himself (according to the kenosis Christ teaches by His example on the Cross) and thus make room for others. This self-emptying is not at all superficial, but very much ontological, such that there is a real identification of the elder with the life of his spiritual child. [7] Such a total commitment to other people requires complete self-sacrifice, as well as advancement along the spiritual path. Without experiential knowledge of the spiritual path the elder is practically unable to help others. [8]

When experiential knowledge of the spiritual path is absent, humanity seeks other ways to deal with its spiritual woes. The solution of modern man has been to provide materialistic answers to spiritual problis. Psychology, modern medicine, and so on attempt to heal man; however, detached as they are from genuine Orthodox Christian spiritual life, their attempts to answer the very deep existential problis of contemporary man remain hopelessly ineffectual. The Holy Spirit, abiding in the Church, and guiding Her into all truth (John 16:13) since Pentecost, has taught the Church the ways of spiritual healing, establishing Her as a "spiritual hospital." The elder acts both as this hospital's finest surgeon as well as its chief medical school instructor. [9]

The Wisdom of the Gospel: Key to the Lives and Counsels

Perhaps the most important interpretive key for approaching the lives and counsels presented herein is the realization that they may only be understood according to their own "logic," which is not the logic of this world. This logic, of course, is none other than the wisdom of Christ's life and Gospel teaching. For contemporary man, however, Christ's wisdom is truly difficult to grasp, it is a "hard" saying, and so the lives and teachings of those who have followed, experientially and existentially, the narrow path of Christ will similarly seem difficult to grasp and a "hard" saying. Early on St. Paul understood this opposition between the wisdom of the world and the wisdom of Christ,

For it is written, I will destroy the wisdom of the wise, and will bring to nothing the understanding of the prudent. Where is the wise? Where is the scribe? Where is the disputer of this world? Hath not God made foolish the wisdom of this world? For after that in the wisdom of God the world by wisdom knew not God, it pleased God by the foolishness of preaching to save them that believe. For the Jews require a sign, and the Greeks seek after wisdom: But we preach Christ crucified, unto the Jews a stumbling block, and unto the Greeks foolishness; but unto them which are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God, and the wisdom of God. Because the foolishness of God is wiser than men; and the weakness of God is stronger than men. (1 Corinthians 1:19-25).

Accepting Christ's message (and the incarnation of this message in the lives of the elders gathered here) is particularly difficult for contemporary people, even faithful Christians, for many of us live most of our lives according to the wisdom of this world and not according to the "foolishness" of the Cross. If one is able at least to understand that a chasm lies between worldly wisdom, and the wisdom of the Gospel, it will make the comprehension of the following lives more realizable. When this shift in vision is realized, it reveals one's poverty of faith, as well as the distance between where one is, and the absolute demands of the Gospel commandments.

For the person who is seeking God the realization of the absolute difference between the wisdom of this world and the wisdom of the Gospel begets repentance. It is significant that the Greek word for repentance, metanoia, means, literally, a "change of mind." This change of mind is a prerequisite for the comprehension of the Gospel, and so it is not surprising that St. John the Baptist began his public ministry with the injunction, "Repent ye: for the kingdom of heaven is at hand." (Matthew 3:2). Likewise, Christ began His ministry with the same message, "From that time Jesus began to preach, and to say, Repent: for the kingdom of heaven is at hand." (Matthew 4:17) That the lives and counsels of the Greek monastic elders contained in this book force the reader to shift to the wisdom of the Gospel testifies to their spiritual ministry as prophets, a ministry that monasticism has always fulfilled. [10]

In the context of the wisdom of the Gospel, those aspects of these lives that surpass human understanding should not shock or scandalize. Christ told His disciples that, "He that believeth on me, the works that I do shall he do also; and greater works than these shall he do." (John 14:12). The Church in Her wisdom and strength has preserved the witness of those who, in the two thousand years since Christ's coming, have followed faithfully in His steps. The lives of the Saints and the writings of ancient and contemporary Fathers of the Church [11] give unquestionable witness to the riches of God's mercy, and the experience of the action of the Holy Spirit. The lives and sayings contained herein are contemporary witnesses to the truth that the Holy Spirit continues to act and to inspire Christians to live lives fully dedicated to Christ.

It is to witness to this truth that the present book has been compiled. It is this witness that is the most precious aspect of these lives (and not their miraculous aspect, impressive though this may be). One may legitimately object, of course, after reading the lives, that the culture in which these men were raised is significantly different from that in which we live. The testimony we have from the Fathers of the Church, however, is that it is not the place that we live that is most significant, but rather the way that we live. They tell us, furthermore, that there are no circumstances that could prevent us from keeping Christ's commandments, from following the way Christ has shown us. [12] This is also the witness of the Scriptures wherein we understand that the Scriptural injunctions are not dependent on time or place, but are always pertinent and binding on man. [13]

To many, the absolute character of Christ's commandments may seem a heavy burden. Again, however, the wisdom of the Gospel surprises us, as Christ says, "Come unto me, all ye that labour and are heavy laden, and I will give you rest. Take my yoke upon you, and learn of me; for I am meek and lowly in heart: and ye shall find rest unto your souls. For my yoke is easy, and my burden is light." (Matthew 11:28-30). [14]

Perhaps more than anything else the lives of the Saints (and of the Greek monastic elders in this book) provide an "interpretation" of Christ's Gospel, "written not with ink, but with the Spirit of the living God; not in tables of stone, but in fleshly tables of the heart." (2 Corinthians 3:3). That which is of greatest importance in these lives are not so much the details of each life, but rather the spirit that breathes in them, which shaped them into precious vessels of the Holy Spirit. These lives bear witness to the transformation of man that is possible, when the Christian gives himself wholly over to the will of God. As Elder Sophrony of Essex has written, it is not arbitrary asceticism or the possession of supernatural gifts that constitute genuine Christian spiritual life, but rather obedience to the will of God. Each person has his own capabilities and his own path to tread; the keeping of Christ's commandments, however, remains a constant. Fr. Sophrony also repeatedly insists, following the teaching of his elder, St. Silouan the Athonite, that the truth or falsity of one's path may be measured, not by one's asceticism or spiritual gifts, but by love for one's enemies, by which St. Silouan did not mean a "scornful pity; for him the compassion of a loving heart was an indication of the trueness of the Divine path." [15] In another place Fr. Sophrony develops this point more fully,

There are known instances when Blessed Staretz Silouan in prayer beheld something remote as though it were happening close by; when he saw into someone's future, or when profound secrets of the human soul were revealed to him. There are many people still alive who can bear witness to this in their own case but he himself never aspired to it and never accorded much significance to it. His soul was totally engulfed in compassion for the world. He concentrated himself utterly on prayer for the world, and in his spiritual life prized this love above all else. [16]

Fr. Sophrony's words reveal to us a mystery of the ways of Christian monasticism and eldership: according to the wisdom of this world, the monastic elder's departure from the world seems like an escape from humanity. The reality, however, is that according to the wisdom of the gospel, separation from the world enables those who love God to love the world more than those who live in the world do. It is this paradox that the monastic elder lives, and an explication of which Dr. Georgios Mantzaridis provides in his Foreword. [17]

Endnotes

For a more complete exposition, the reader may want to consult Bishop Kallistos Ware's "The Spiritual Father in Saint John Climacus and Saint Symeon the New Theologian," published in Studia Patristica XV111/2. Kalamazoo: Cistercian Publications-Leuven: Peeters, 1990. This article may also be found as the Foreword of Irenee Hausherr's Spiritual Direction in the Early Christian East. Kalamazoo, MI: Cistercian Publications, 1990, p. vii-xxxiii, from which we quote. Also, by the same author, "The Spiritual Guide in Orthodox Christianity," published in The Inner Kingdom: Volume One of the Collected Works. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Press, 2000, p. 127-151.Bishop Kallistos Ware, "The Spiritual Father in Saint John Climacus and Saint Symeon the New Theologian," p. vii.Kenosis/kenotic : Greek word meaning "self-emptying."We are not aware of a sufficient study in English that addresses the crucial difference between an ethical and an ontological understanding of Christianity, although it is touched upon in Eugene Rose's (the future Fr. Seraphim Rose) "Christian Love," in Heavenly Realm. Platina, CA: St. Herman Brotherhood, 1984, p. 27-29.As St. John Chrysostom assures us, "He [St. Paul] is not setting forth his dignity herein, but the excess of his love." [Homily 13, PG 61:111 (col. 109). Translation: Homilies. Found in The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church. First Series. Edited by Philip Schaff, D.D., LL.D. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Vol. XII, 1969 (reprint).]Bishop Kallistos Ware, ibid., p. viii-ix.This is the deeper meaning of Christ's second commandment, "Thou shalt love... thy neighbor as thyself." (Luke 10:27). St. Silouan the Athonite taught that this love is not quantitative (i.e., "as much as you love yourself," but qualitative (i.e., "in the same way as you love yourself,") thus emphasizing that the perfection of love for others is realized in one's complete identification with them. Dr. Mantzaridis, in his Foreword, which follows, develops precisely this point. It is only in humanity's identification with Christ and with its neighbor that the true union of mankind is possible.St. John Climacus explains this necessary aspect of the elder: "A genuine teacher is he who has received from God the tablet of spiritual knowledge, inscribed by His Divine finger, that is, by the in-working of illumination, and who has no need of other books." [Ad Pastorem. PG 88: 1165B. Translation: Archimandrite Lazarus Moore, The Ladder of Divine Ascent. Brookline, MA: Holy Transfiguration Monastery, 1991, p. 231.It should be noted that this charismatic ministry is not at odds with the ministry of the priest-confessor. On the contrary, both have as their goal the reconciliation of man with God. Although the priest-confessor's ministry of guidance may be hindered by the absence of experiential knowledge of the ways of spiritual growth and healing, he still bears the responsibility and blessing to hear confession, to forgive man his sins, and to reconcile man to God. For more on the Orthodox understanding of the Church as spiritual hospital, see Metropolitan Hierotheos Vlachos' Orthodox Psychotherapy. Levadia, Greece: Birth of the Theotokos Monastery, 1994."And God hath set some in the church, first apostles, secondarily prophets, thirdly teachers...." (1 Corinthians 12:28). This prophetic ministry was central to both the Old and New Testaments. The roots of monasticism lie in this ancient ministry, which is not so much concerned with telling the future (although this aspect of its ministry continues up to the present day), as calling the world to a change of heart, to repentance, so that the world might more easily accept the gospel message.Fathers of the Church: This term is used in the Orthodox Church to refer to Saints of all times whose teaching has been accepted by the Church as an authentic expression of Her life and faith. Roman Catholics tend to define this term more narrowly, limiting the Fathers to those Saints of the Church who lived during the "golden age" of theology, in the first millennium of Christianity, whose writings played a significant role in the development of the dogmatic expression of the faith.St. Symeon the New Theologian goes so far as to say that to believe otherwise is heresy, "But the men of whom I speak and whom I call heretics are those who say that there is no one in our times and in our midst who is able to keep the Gospel commandments and become like the holy Fathers." The Discourses. (Translation by C.J. deCatanzaro), Mahwah, NJ: Paulist Press, 1980, p. 312. See also, Archimandrite Sophrony Sakharov, St. Silouan the Athonite. Essex, England: Stavropegic Monastery of St. John the Baptist, 1991, p. 242-243.See, Matthew 5:18, 24:35, Mark 13:31, Luke 21:33, etc.St. John Chrysostom interprets this passage precisely within the framework we have discussed, in relation to man's attempt to be faithful to Christ's commandments, "But if virtue seems a difficult thing, consider that vice is more difficult.... Sin too has labor, and a burden that is heavy and hard to bear.... For nothing so weighs upon the soul, and presses it down, as consciousness of sin; nothing so gives it wings, and raises it on high, as the attainment of righteousness and virtue.... If we pursue such a philosophy, all these things are light, easy, and pleasurable.... Virtue's yoke is sweet and light." [Homily 38, PG 57: 428-431 (cols. 431-434). Translation: Homilies on the Gospel of St. Matthew. Found in The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church. First Series. Translated by Rev. Sir George Prevost, Barontet, M.A., Philip Schaff, D.D., LL.D. Edited and revised, with notes by Rev. M. B. Riddle, D.D. Grand Rapids, MI: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Company, Vol. X, 1975].Archimandrite Sophrony Sakharov, St. Silouan the Athonite, p. 228.Ibid., p.130.One final note on the application of the spiritual principles found in this book to one's own life; as with all aspects of the spiritual life, spiritual guidance is a necessary prerequisite for spiritual growth.

tips on prayer from the desert fathers

a wonderful revelation to the world

THE IDEAL OF MONASTIC LOVE

One learns the discipline of service in community. And it is this discipline which in turn opens one to the workings of the Spirit.

For a group of men to live together in harmony and peace there must be sacrifice and generosity. The good of the brothers and the interests of others must often take precedence over one's own desires. Selfless service of others is a great school of love.

And yet it is love of a particular sort. It is different from familial love, since the monastery is not strictly speaking a family. The relation of husband and wife, parents and children is not there. We speak of the "monastic family", but only in a loose sense of the word. It would be fatal to look for the monastic community to supply what one would normally have in a family.

It is more than fraternal love, since a monastery is not just a fraternity. One does speak more correctly of the monks having brotherly love for one another, yet even this must be understood correctly. They are more than "buddies." More than comrades. More even than brothers in the flesh. Their love for one another is primarily in Christ. It is because they love Christ that they love one another.

The ideal of monastic love is noble and not easily come by. It takes time and effort and grace to bring it about. But a community of men with genuine love for one another in Christ is a great joy. It is a profound force in the world, able to move mountains. It will not always be obvious, even to those who share in it. This kind of love is deeper than smiles and camaraderie, a certain effusive sentiment. It is a kind of love that makes death for one's brother easy and understandable

Thus monks wash each other's clothes and do the dishes and cook the food; they clean toilets and type letters and make fruitcakes, and get dinner ready. They work, in other words, and endeavor to work literally for love.

And it is this discipline of service which opens the heart and makes a man available to the Lord who would woo his heart if He could get close enough. It is service that lets God in because selfishness is in the process of being driven out.

-- Fr Matthew Kelty

CHRIST LEADS US IN UNIQUE WAYS

The monk gives body to one aspect of the Christian life, and that is prayer, particularly prayer in solitude. The monk is with Christ on the mountain alone at night, with Christ in the forty days in the desert, in the garden of Gethsemani, in the hidden years. But those in monastic life are not his companion in the ministry, in the healing, in his miracles, or even in his passion and death. The Christ at prayer is the monk's Christ and everything follows from that, though what follow may well include ministry, preaching, miracles, passion and death, should God will.

No one can follow Christ in everything, but one can follow Christ with a particular attention to a particular aspect of his life.

We do not take Christ apart; Christ is whole and cannot be divided. Yet, in our accompanying him we are with him sometimes visibly and sometimes not, most often not.

Christ did nothing worthwhile for thirty years. One carpenter more or less in Nazareth could scarcely have mattered. For all practical purposes, they were wasted years. And it is precicely to that kind of waste that most people are called. And even within the scope of his few public years, Christ was wont to waste further time by running off to the hills when there was work to be done. Even in the few years he did apostolic work, as we call it, he reached few, healed fewer, and in the end succeeded only in raising so much opposition and ill-will that they put him to death.

In all of that I see no justification whatever for the notion that work for God necessarily means a life of feverish action.

As for the monks....... The futility of saying: "What good is it? What use? Who needs it? Who needs incense? Who needs bells? Can't you get yourself a watch? Who needs cowls and choir stalls and cloister and abbot?" No one, really, if that is your approach. Who needs song and dance? Who needs processions and icons and candles? Candles --- in the monastic church.... All these lights on --- 39 of them, 12,000 watts --- and you light candles. This is madness.

In a context of beauty and peace, barren of noise and strife, some people thrive. Call it a contemplative identity if you will, a certain cast of soul that prefers inner to outer, pondering to preaching, quiet to action.

That's why Brother Joachim was right when he answered the question of a couple wandering in the woods: "What do you do?"

"I am a monk."

"We know that. But what do you do?"

And Brother Joachim answered with that intensity he is capable of: "I am a monk."

So I pass the question to you: "What do you do?"

--- Fr Matthew Kelty

SOME WORDS OF CAUTION

Some kinds of people are much drawn to monasteries and must be warned that such a life is not good for them, and may even do them much harm. Normally such persons will be noted before they enter, but a great deal of anguish can be spared them if they do not even move that far along the road toward something that is not meant for them.

People with emotional hang-ups of serious dimensions - enough to require hospitalization - ought to stay clear of monasteries no matter how strongly they feel God is calling them to enter one.

Let us put it plainly: monastic life is no picnic. Day by day there is really nothing very difficult about it, but put a number of days in a row, one after another, and certain types are apt to climb the walls. Some people cannot stand silence, seclusion, quiet, a lack of excitement and diversion.

If you do not like people, the monastery is no place to go. If you hate the world, this is no place to come. If you get moody and depressed, this will crush you for sure.

To ask for healthy young men from a culture such as ours is to ask a great deal. But there must be a certain amount of good sense, of courage, and of enthusiasm. There will have to be a love for life and a desire to truly live.

Narrowing it down to what makes the contemplative calling we might add: a sense of wonder.

And a certain intuitive grasp that there is something else beside action. That while action is good enough and absolutely necessary, there is another side of the coin: there is something to be said for musing, for pondering, for mulling.

There ought to be a desire to go to some place where men pray, yes; where they work, yes; where they read good books, yes ..but in addition to that, where they do nothing. Where the pause that refreshes is not a drink .... A place for men who love the night, and know the moon, who listen to birds sing and watch the wind in the grass on the hill.

And men who can take discipline, can accept the responsibility of being who they are and what they are.

Fr Matthew Kelty

SILENCE

Perhaps one of the things that is envied in the monk's life is his silence. In a world becoming daily more noisy, the idea of quiet, of a life in which there are areas of silence becomes very attractive.

Silence is a privilege to which all are entitled and of which most are robbed in this age. The monk is not a freak for loving silence; he is simply normal and human.

Silence is a real part of monastic life. It is perhaps the greatest single factor in spiritual growth. Without it nothing happens.

It is not a matter of taciturnity. Men who do not easily and happily communicate with their fellowmen do not make good monks. A lack of sensitivity to others is no sign of a Trappist vocation. On the other hand, the monk must gradually acquire a feeling for silence.

One reason monks rise early to pray is the quiet of night. Darkness is a kind of visual quiet and monks love it. The hours before dawn are sacred.

Silence need not make monks a weird crew, though this sometimes happens when common sense is abandoned. Monks in former times went to great lengths to "keep silence."

Their efforts strike modern people as somewhat theatrical and showy. But unless a man can see the point of silence he might just as well not bother coming to the monastery. It is inevitable that the whole thing will never mean anything to him. He has to have a feeling for this kind of thing.

Simply has to.

* * *

Before speaking about the baptism, or outpouring, in the Spirit, I think it is important to understand what the renewal in the Spirit is, where this experience happens and of which it constitutes the source and the high point. Then we will better understand that the outpouring is not an event in and of itself but rather the beginning of a journey whose aim is the profound renewal of life in the whole Church.

Renewal in the Spirit

The expression “renewal in the Spirit” has two biblical equivalents in the New Testament. To understand the soul of the charismatic movement, its profound inspiration, we must primarily search the Scripture. We need to discover the exact meaning of this phrase that is used to describe the experience of the renewal.

The first text is in Ephesians 4:23-24: “Be renewed in the spirit of your minds and . . . clothe yourselves with the new self.” Here the word “spirit” is written with a small “s,” and rightly so, because it indicates “our” spirit, the most intimate part of us (the spirit of our minds), which Scripture generally calls “the heart.” The word “spirit” here indicates that part of ourselves that needs to be renewed in order for us to resemble Christ, the New Man par excellence. “Renewing ourselves” means striving to have the same attitude that Christ Jesus had (see Philippians 2:5), striving for a “new heart.”

This text clarifies the meaning and the aim of our experience: The renewal should be, above all, an interior one, one of the heart. After the Second Vatican Council, many things were renewed in the church: liturgy, pastoral care, the Code of Canon Law and religious constitutions and attire. Despite their importance, these things are only the antecedents of true renewal. It would be tragic to stop at these things and to think that the whole task has been completed.

What matters to God is people, not structures. It is souls that make the church beautiful, and therefore she must adorn herself with souls. God is concerned about the hearts of His people, the love of His people, and everything else is meant to function as a support to that priority.

Our first text is not enough, however, to explain the phrase “renewal in the Spirit.” It highlights our obligation to renew ourselves (“be renewed!”) as well as what must be renewed (the heart), but it doesn’t tell us the “how” of renewal. What good is it to tell us we “must” renew ourselves if we are not also told how to renew ourselves? We need to know the true author and protagonist of the renewal.

Our second biblical text, from Titus, addresses that precise issue. It says that God “saved us, not because of any works of righteousness that we had done, but according to his mercy, through the water of rebirth and renewal by the Holy Spirit” (Titus 3:5).

Here “Spirit”has a capital“S” because it points to the Spirit of God, the Holy Spirit. The preposition “by”points to the instrument, the agent. The name we give to our experience signifies, then, something very exact: renewal by the work of the Holy Spirit, a renewal in which God, not man, is the principal author, the protagonist. “I [not you]” says God, “am making all things new” (Revelation 21:5); “My Spirit [and only He] can renew the face of the earth” (see Psalm 104:30).

This may seem like a small thing, a simple distinction, but it actually involves a real Copernican revolution—a complete reversal that people, institutions, communities and the whole church in its human dimension must undergo in order to experience a genuine spiritual renewal.

We often think according to the “Ptolemaic system”: Its foundation consists in efforts, organization, efficiency, reforms and good will. The “earth” is at the center of this scheme, and God comes with His grace to empower and crown our efforts. The “Sun” revolves around the earth and is its vassal; God is the satellite of man.

However, the Word of God declares, “We need to give the power back to God” (see Psalm 68:35) because the “power belongs to God” (Psalm 62:11). That is a trumpet call! For too long we have usurped God’s power, managing it as though it were ours, acting as though it were up to us to “govern” the power of God. Instead, we need to revolve around the “Sun.” That’s the Copernican revolution I’m talking about.

Through that kind of revolution, we recognize, simply, that without the Holy Spirit we can do nothing. We cannot even say, “Jesus is Lord!” (see 1 Corinthians 12:3). We recognize that even our most concerted effort is simply the effect of salvation, rather than its cause. Now we can begin to really “lift up our eyes” and to “look up,” as the prophet exhorts (see Isaiah 60:4), and to say, “I lift up my eyes to the hills—from where will my help come? My help comes from the Lord, who made heaven and earth” (Psalm 121:1-2).

The Bible often repeats the command of God, “You shall be holy, for I the Lord your God am holy!” (Leviticus 19:1; see Leviticus 11:44; 1 Peter 1:15-16). But in one place in that very same book of Leviticus, we find a statement that explains all the others: “I am the Lord; I sanctify you!” (Leviticus 20:8). I am the Lord who wants to renew you with My Spirit! Let yourselves be renewed by My Spirit!

Baptism: An “Unreleased” Sacrament

Now let’s move on to the theme of the baptism of the Spirit. First of all it must be said that this expression is not a recent invention of pentecostals and charismatics. It comes directly from Jesus. Before leaving his disciples he said to them: “John baptized in water but, not many days from now, you are going to be baptized with the Holy Spirit” (Ac 1:5). We know what happened not many days from that moment: Pentecost! The expression baptism in the Spirit therefore on one hand refers to the event of Pentecost and on the other hand to baptism. We could speak of it in terms of “ a new Pentecost” for the church (and I often do so) or in terms of a renewal of our baptism. This time I want to explore this second dimension of it.

The term “baptism in the Spirit” indicates that there is something here that is basic to baptism. We say that the outpouring of the Spirit actualizes and revives our baptism. To understand how a sacrament received so many years ago and administered in infancy can suddenly come alive and be revived and release such energy as we see on the occasions of outpouring, we must recall some aspects of sacramental theology.

Catholic theology can help us understand how a sacrament can be valid and legal but “unreleased.” A sacrament is called “unreleased” if its fruit remains bound, or unused, because of the absence of certain conditions that further its efficacy. One extreme example would be the sacrament of marriage or of holy orders received while a person is in the state of mortal sin. In those cases, such sacraments cannot confer any grace on a person. If, however, the obstacle of sin is removed by repentance, the sacrament is said to revive (reviviscit) due to the faithfulness and irrevocability of the gift of God. God remains faithful even when we are unfaithful, because He cannot deny Himself (see 2 Timothy 2:13).

There are other cases in which a sacrament, while not being completely ineffective, is nevertheless not entirely released: It is not free to works its effects. In the case of baptism, what is it that causes the fruit of this sacrament to be held back?

Here we need to recall the classical doctrine about sacraments. Sacraments are not magic rites that act mechanically, without people’s knowledge or collaboration. Their efficacy is the result of a synergy, or collaboration, between divine omnipotence (that is, the grace of Christ and of the Holy Spirit) and free will. As Saint Augustine said, “He who created you without your consent will not save you without your cooperation.”

To put it more precisely, the fruit of the sacrament depends wholly on divine grace; however, this divine grace does not act without the “yes”—the consent and affirmation—of the person. This consent is more of a “conditio sine qua non” than a cause in its own right. God acts like the bridegroom, who does not impose his love by force but awaits the free consent of his bride.

God’s Role and Our Role in Baptism

Everything that depends on divine grace and the will of Christ in a sacrament is called “opus operatum,” which can be translated as “the work already accomplished, the objective and certain fruit of a sacrament when it is administered validly.” On the other hand, everything that depends on the liberty and disposition of the person is called “opus operantis”; this is the work yet to be accomplished by the individual, his or her affirmation.

The opus operatum of baptism, the part done by God and grace, is diverse and very rich: remission of sins; the gift of the theological virtues of faith, hope and charity (given in seed form); and divine sonship. All of this is mediated through the efficacious action of the Holy Spirit. In the words of Clement of Alexandria:

Once baptized, we are enlightened; enlightened, we are adopted as sons; adopted, we are made perfect; made perfect, we receive immortality . . . . The operation of baptism has several names: grace, enlightenment, perfection, bath. It can be called a “bath” because through it we are purified of our sins; “grace” because the punishments deserved for our sins are removed; “enlightenment” because through it we can contemplate the beautiful and holy light of salvation, and see into divine reality; “perfection” because nothing is lacking.

Baptism is truly a rich collection of gifts that we received at the moment of our birth in God. But it is a collection that is still sealed up. We are rich because we possess these gifts (and therefore we can accomplish all the actions necessary for Christian life), but we don’t know what we possess. Paraphrasing a verse from John, we can say that we have been sons of God until now, but what we shall become has yet to be revealed (see 1 John 3:2). This is why we can say that, for the majority of Christians, baptism is a sacrament that is still “unreleased.”

So much for the opus operatum. What does the opus operantis consist of in baptism?

It consists of faith! “The one who believes and is baptized shall be saved” (Mark 16:16). With regard to baptism, then, there is the element of a person’s faith. “But to all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God” (John 1:12).

We can also recall the beautiful text from the Acts of the Apostles that tells about the baptism of Queen Candace’s court official. When their journey brought Philip and the official near some water, the official said, “‘Look, here is water! What is to prevent me from being baptized?’ Philip said, ‘It is permitted if you believe with all your heart’ ” (Acts 8: 36-37). (Verse 37 here, an addition from the early Christian community, testifies to the common conviction of the church at that time.)

Baptism is like a divine seal stamped on the faith of man: “When you had heard the word of truth, the gospel of your salvation, and had believed in him, [you] were marked with the seal [this refers to baptism] of the promised Holy Spirit” (Ephesians1:13). Saint Basil wrote, “Truly, faith and baptism, these two modes of salvation, are bound indivisibly to one another, because if faith receives its perfection from baptism, baptism is founded on faith.” This same saint called baptism “the seal of faith.”

The individual’s part, faith, does not have the same importance and independence as God’s action because God plays a part even in someone’s act of faith: Even faith works by the grace that stirred it up. Nevertheless, the act of faith includes, as an essential element, the response—the individual’s “I believe!”—and in that sense we call it opus operantis, the work of the person being baptized.

Now we can understand why baptism was such a powerful and grace-filled event in the early days of the church and why there was not normally any need for a new outpouring of the Spirit like the one we are experiencing today. Baptism was administered to adults who were converting from paganism and who, after suitable instruction, were in a position to make an act of faith, an existential, free and mature choice about their lives. (We can read about baptism in the Mystagogical Catecheses, attributed to Cyril of Jerusalem, to understand the depth of faith of those who were prepared for baptism.)

They came to baptism by way of a true and genuine conversion. For them baptism was really a font of personal renewal in addition to a rebirth in the Holy Spirit (see Titus 3:5). Saint Basil, responding to someone who had asked him to write a treatise on baptism, said that it could not be explained without first explaining what it means to be a disciple of Jesus, because the Lord commands,

Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, and teaching them to obey everything that I have commanded you. –MATTHEW 28:19-20

In order for baptism to operate in all its power, anyone who desires it must also be a disciple or have a serious intention of becoming one. According to Saint Basil:

A disciple is, as the Lord Himself taught us, anyone who draws near to the Lord to follow Him, that is, to hear His Words, to believe and obey Him as one would a master or a king or a doctor or a teacher of truth. . . . Now, whoever believes in the Lord and presents himself ready to be disciple must first set aside every sin and everything that distracts from the obedience which is owed to the Lord for many reasons.

The favorable circumstance that allowed baptism to operate in such power at the beginning of the church was this: The action of God and the action of man came together simultaneously, with perfect synchronism. It happened when the two poles, one positive and one negative, touched, making light burst forth.

Today this synchronism is usually not operative. As the church adopted infant baptism, little by little the sacrament began to lack the act of faith that was free and personal. The faith was supplied, or uttered, by an intermediate party (parents and godparents) on behalf of the child. In the past, when the environment around the baby was Christian and full of faith, the child’s faith could develop, even if it was slowly. But today our situation has become even worse than that of the Middle Ages.

The environments in which many children now grow up do not help faith to blossom. The same must often be said of the family, and more so of the child’s school and even more so of our society and culture. This does not mean that in our situation today normal Christian life cannot exist or that there is no holiness or no charisms that accompany holiness. Rather, it means that instead of being the norm, it has become more and more of an exception.

In today’s situation, rarely, or never, do baptized people reach the point of proclaiming “in the Holy Spirit” that “Jesus is Lord!” And because they have not reached that point, everything in their Christian lives remains unfocused and immature. Miracles no longer happen. What happened with the people of Nazareth is being repeated: “Jesus was not able to do many miracles there because of their unbelief” (see Matthew 13:58).

The Meaning of the Ourpouring of the Spirit

The outpouring of the Spirit, then, is a response by God to the dysfunction in which Christian life now finds itself. In these last few years we know that the church, the bishops, have also begun to be concerned that Christian sacraments, especially baptism, are being administered to people who will make no use of them in their lives. Thus, they have considered the possibility of not administering baptism when the minimum guarantees that this gift of grace would be valued and cultivated are absent.

We cannot, in fact, “throw our pearls before swine,” as Jesus said, and baptism is a pearl because it is a fruit of the blood of Christ. But we can say that God is concerned, even more than the church is, about this dysfunction. He has raised up movements here and there in the church that are proceeding in the direction of renewing Christian initiation among adults.

The renewal in the Spirit is one of those movements, and its principal grace, without doubt, is tied to the outpouring of the Spirit and what precedes it. Its efficacy at revivifying baptism consists in this: Finally a person is doing his or her part, making a decision of faith that is prepared through repentance. This allows the work of God to “be released” in all its power.

It is as though God’s outstretched hand has finally grasped the hand of the individual, and through that handclasp, He transmits all His creative power, which is the Holy Spirit. To use an image from physics, the plug has been inserted into the outlet, and the light has been turned on. The gift of God is finally “unbound,” and the Spirit permeates Christian life like a perfume.

For the adult who has been a Christian for many years, this faith decision necessarily has the characteristic of a conversion. We could describe this outpouring of the Spirit, insofar as the person is concerned, either as a renewal of baptism or as a second conversion.

We can understand something else about this outpouring if we also see its connection with confirmation, at least in the current practice of separating it from the sacrament of baptism and administering it later. In addition to being a renewal of the grace of baptism, the outpouring is also a “confirmation” of baptism itself, a conscious “yes” to it, its fruit and its commitments. As such it parallels (at least in its subjective aspect) the effects of confirmation on the objective, sacramental level.

Confirmation is understood as a sacrament that develops, confirms and fulfills the work of baptism. The outpouring is a subjective and spontaneous—not sacramental—confirmation in which the Spirit acts not from the power of the sacramental institution but through the power of His free initiative and the openness of the person.

The meaning of confirmation sheds light on the special sense of greater involvement in the apostolic and missionary dimension of the church that usually characterizes someone who has received the outpouring of the Spirit. That person feels impelled to help build up the church, to serve the church in various ministries, clerical or lay, and to give testimony to Christ. All of these things recall Pentecost and actualize the sacrament of confirmation.

Jesus, “The One Who Baptizes in the Holy Spirit”

The outpouring of the Holy Spirit is not the only occasion in the church for this renewal of the sacraments of initiation and, in particular, of the coming of the Holy Spirit at baptism. Other occasions include the renewal of baptismal vows during Easter vigils; spiritual exercises; the profession of vows, called “a second baptism”; and, on the sacramental level, confirmation.

It is not difficult, then, to find the presence of a “spontaneous outpouring” in the lives of the saints, especially on the occasion of their conversion. For example, we can read about Saint Francis at his conversion:

After the feast they left the house and started off singing through the streets. Francis’ companions were leading the way; and he, holding his wand of office, followed them at a little distance. Instead of singing, he was listening very attentively. All of a sudden the Lord touched his heart, filling it with such surpassing sweetness that he could neither speak nor move. He could only feel and hear this overwhelming sweetness which detached him so completely from all other physical sensations that, as he said later, had he been cut to pieces on the spot he could not have moved.

When his companions looked around, they saw him in the distance and turned back. To their amazement they saw that he was transformed into another man, and they asked him, “What were you thinking of? Why didn’t you follow us? Were you thinking of getting married?”

Francis answered in a clear voice: “You are right: I was thinking of wooing the noblest, richest, and most beautiful bride ever seen.” His friends laughed at him saying he was a fool and did not know what he was saying; in reality he had spoken by a divine inspiration.

Although I said the outpouring of the Spirit is not the only time of renewal of baptismal grace, it holds a very special place because it is open to all of God’s people, big and small, and not just to certain privileged people who do the Ignatian spiritual exercises or take religious vows. Where does that extraordinary power that we have experienced in an outpouring come from? We are not, in fact, speaking about a theory but about something that we ourselves have experienced. We can also say, with Saint John, “What we have heard, and what we have seen with our own eyes and touched with our own hands, we declare to you because you are in communion with us” (see 1 John 1:1-3). The explanation for this power lies in God’s will: It has pleased Him to renew the church of our day by this means, and that is all there is to it!

There are certainly some biblical precedents for this outpouring, like the one narrated in Acts 8:14-17. Peter and John, knowing that the Samaritans had heard the Word of God, came to them, prayed for them and laid hands on them to receive the Holy Spirit. But the text that we need to begin with to understand something about this baptism in the Spirit is primarily John 1:32-33:

And John [the Baptist] testified, “I saw the Spirit descending from heaven like a dove, and it remained on him. I myself did not know him, but the one who sent me to baptize with water said to me, ‘He on whom you see the Spirit descend and remain is the one who baptizes with the Holy Spirit.’”

What does it mean that Jesus is “the one who baptizes in the Holy Spirit”? The phrase serves not only to distinguish the baptism of Jesus from that of John, who baptized only “with water,” but to distinguish the whole person and work of Christ from His precursor’s. In other words, in all His works, Jesus is the one who baptizes in the Holy Spirit.

“To baptize” has a metaphoric significance here: It means “to flood, to bathe completely and to submerge,” just as water does with bodies. Jesus “baptizes in the Holy Spirit” in the sense that he “gives the Spirit without measure” (see John 3:34), that He has “poured out” His Spirit (see Acts 2:33) on all of redeemed humanity. The phrase refers to the event of Pentecost more than to the sacrament of baptism, as one can deduce from the passage in Acts: “John baptized with water, but you will be baptized with the Holy Spirit not many days from now” (Acts 1:5).

The expression “to baptize in the Holy Spirit” defines, then, the essential work of Christ, which already in the messianic prophecies of the Old Testament appeared oriented to regenerating humanity by means of a great outpouring of the Holy Spirit (see Joel 2:28-29). Applying all this to the life and history of the church, we must conclude that the resurrected Jesus baptized in the Holy Spirit not only in the sacrament of baptism but in different ways and at different times as well: in the Eucharist, in the hearing of the Word of God, in all other “means of grace.”

The baptism in the Spirit is one of the ways that the resurrected Jesus continues his essential work of “baptizing in the Spirit.” For this reason, even though we can explain this grace in reference to baptism and Christian initiation, we need to avoid becoming rigid about his point of view. It is not only baptism that revives the grace of initiation, but also confirmation, first communion, the ordination of priests and bishops, religious vows, marriage—all the graces and charisms. This is truly the grace of a new Pentecost. It is, like the rest of Christian life, a new and sovereign initiative, in a certain sense, of the grace of God, which is founded on but not exhausted in baptism. It is linked not just to “initiation” but also to the “perfection” of Christian life.

Only in this way can we explain the presence of the baptism in the Spirit among Pentecostal brothers and sisters. The concept of initiation is foreign to them, and they do not invest the same importance in water baptism as do Catholics and other Christians. In its very origin the baptism in the Spirit has an ecumenical value, which is necessary to preserve at all costs. It is a promise and an instrument of unity among Christians, helping us to avoid an excessive “catholicizing” of this shared experience.

Brotherly Love, Prayer and Laying on of Hands

In the outpouring there is a hidden, mysterious dimension that is different for each person because only God knows us intimately. He acts in a way that respects the uniqueness of our personalities. At the same time, there is also a visible dimension, in the community, that is the same for all and that constitutes a kind of sign, analogous to the signs in the sacraments. The visible, or community, dimension consists primarily in three things: brotherly love, prayer and the laying on of hands. These are not sacramental signs, but they are indeed biblical and ecclesial.

The laying on of hands can signify two things: invocation or consecration. We see, for example, both types of laying on of hands at Mass. There is the laying on of hands as invocation (at least in the Roman rite) at the moment of epiclesis, when the priest prays, “May the Holy Spirit sanctify these gifts so that they may become for us the body and blood of Our Lord Jesus Christ.” Then there is the laying on of hands when the concelebrants pray over the offerings at the moment of consecration.

In the rite of confirmation, as it now occurs, there are also two occasions for the laying on of hands. The first has the character of invocation. The other, which accompanies the anointing with the oil of chrism on the forehead, by which the sacrament becomes actualized, has the character of consecration.

In the outpouring of the Spirit, the laying on of hands has only the character of invocation (similar to what we find in Genesis 48:14; Leviticus 9:22; Mark 10:13-16; Matthew 19:13-15). It also has a highly symbolic significance: It recalls the image of the Holy Spirit’s overshadowing (see Luke 1:35); it also recalls the Holy Spirit as He “swept over” the face of the waters (see Genesis 1:2). In the original the word that is translated “swept over” means “to cover with one’s wings,” or “to brood, like a hen with her chicks.”

Tertullian clarifies the symbolism of the laying on of hands in baptism: “The flesh is covered over by the laying on of hands so that the soul can be enlightened by the Spirit.” This action is a paradox, like many things in God: The laying on of hands enlightens by covering, like the cloud that followed the chosen people in Exodus and like the one that surrounded the disciples on Mount Tabor (see Exodus 14:19-20; Matthew 17:5).

The other two elements are brotherly love and prayer, or “brotherly love that expresses itself in prayer.” Brotherly love is the sign and vehicle of the Holy Spirit. He, who is Love, finds a natural environment in brotherly love, His sign par excellence. (We can also say this love is like a sacramental sign, even if it is in a different sense: “a signifying cause.”) We cannot insist enough on the importance of an atmosphere of brotherly love surrounding those who are going to receive the baptism of the Holy Spirit.

Prayer is also closely connected with the outpouring of the Spirit in the New Testament. Concerning Jesus’ baptism, Luke writes, “While he was in prayer, the heavens opened and the Holy Spirit descended upon him” (see Luke 3:21). It was Jesus’ prayer, we could say, that made the heavens open and the Holy Spirit descend upon Him.

The outpouring at Pentecost happened this way too: While they were all continuing in prayer, there came the sound of a violent wind, and tongues of fire appeared (see Acts 1:14-21). Jesus Himself said, “I will ask the Father, and he will give you another Advocate” (John 14:16). On every occasion the outpouring of the Spirit is connected to prayer.

These signs–the laying on of hands, brotherly love and prayer–all point to simplicity; they are simple instruments. Precisely because of this, they bear the mark of God’s action. Tertullian writes of baptism:

There is nothing which leaves the minds of men so amazed as the simplicity of the divine actions which they see performed and the magnificence of the effects that follow. . . . Simplicity and power are the prerogatives of God.

This is the opposite of what the world does. In the world the bigger the objectives are, the more complicated are the means. When people wanted to get to the moon, the necessary apparatus was gigantic.

If simplicity is the mark of divine action, we need to preserve it in our prayer for the outpouring of the Spirit. Simplicity should shine forth in prayers, in gestures, in everything. There should be nothing theatrical, no excited movements or excessive words, etc.

The Bible records the glaring contrast between the actions of the priests of Baal and the prayer of Elijah during the sacrifice on Mount Carmel. The former cried out, limped around the altar and cut themselves until they bled. Elijah simply prayed, “O Lord, God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, . . . answer me, so that this people may know that you, O Lord, are God, and that you have turned their hearts back!” (1 Kings 18:36-37). The fire of the Lord fell on the sacrifice prepared by Elijah but not on the one prepared by the priests of Baal (see 1 Kings 18:25-38). Elijah later experienced that God was not in the great wind, or in the earthquake, or in the fire but in the still, small voice (see 1 Kings 19:11-12).

From where does the grace of the outpouring come? From the people present? No! From the person who receives? Again, no! It comes from God. It makes no sense to ask if the Holy Spirit comes from inside or from outside of the person: God is inside and outside. We can only say that such grace has a connection to baptism because God always acts with consistency and faithfulness; He does not contradict Himself. He honors the commitment and the institutions of Christ. One thing is certain: It is not the brothers and sisters who confer the Holy Spirit. Rather, they invite the Holy Spirit to come upon a person. No one can give the Spirit, not even the pope or a bishop, because no one possesses the Holy Spirit. Only Jesus can actually give the Holy Spirit. People do not possess the Holy spirit, but, rather, are possessed by Him.

When we talk about the mode of this grace, we can speak of it as a new coming of the Holy Spirit, as a new sending of the Spirit by the Father through Jesus Christ or as a new anointing corresponding to a new level of grace. In this sense the outpouring, although not a sacrament, is nevertheless an event, a spiritual event. This definition corresponds most closely to the reality of the thing. It is an event, something that happens and that leaves a sign, creating something new in a life. It is a spiritual event, rather than an outwardly visible, historical one, because it happens in a person’s spirit, in the interior part of a person, where others may not recognize what is happening. Finally, it is spiritual because it is the work of the Holy Spirit.

There is a wonderful text from the apostle Paul that speaks specifically of the renewing of the gift of God. Let’s hear it as an invitation addressed to each of us:

please click on (mp3):

Fr. George Nicozisin

Speaking in Tongues, "Glossolalia," a popular practice with many Churches today, is a phenomenon which can be traced to the days of the Apostles. A decade ago, Speaking in Tongues was encountered only in Pentecostal Churches, Revival Meetings, Quaker gatherings and some Methodist groups. Today, Glossolalia is also found in some Roman Catholic and Protestant Churches.

The Greek Orthodox Church does not preclude the use of Glossolalia, but regards it as one of the minor gifts of the Holy Spirit. If Glossolalia has fallen out of use it is because it served its purpose in New Testament times and is no longer necessary. However, even when used, it is a private and personal gift, a lower form of prayer. The Orthodox Church differs with those Pentecostal and Charismatic groups which regard Glossolalia as a pre requisite to being a Christian and to having received the Holy Spirit.

Serapion of Egypt, a fourth century contemporary of St. Athanasios summarized Eastern Orthodox theology:

"The Anointing after Baptism is for the Gifts of the Holy Spirit, that having been born again through Baptism and made new through the laver of regeneration, the candidates may be made new through the gifts of the Holy Spirit and secured by this Seal may continue steadfast."

Bishop Maximos Aghiorghoussis, Greek Orthodox Diocese of Pittsburgh and world-renowned Orthodox theologian on the Holy Spirit states it this way: "For Orthodox Christians, Baptism is our personal Paschal Resurrection and Chrismation is our personal Pentecost and indwelling of the Holy Spirit."

There are two forms of Glossolalia:

Pentecost Glossolalia happened this way: Fifty days after the Resurrection, while the disciples were gathered together, the Holy Spirit descended upon them and they began to speak in other languages. Jews from all over the civilized world who were gathered in Jerusalem for the religious holiday stood in amazement as they heard the disciples preaching in their own particular language and dialect (like in a United Nations Assembly). They understood!

Corinthian Glossolalia is different. St. Paul, who had founded the Church of Corinth, found it necessary to respond to some of their problems, i.e., division of authority, moral and ethical problems, the eucharist, the issue of death and resurrection and how the Gifts of the Holy Spirit operated. In chapter 12, St. Paul lists nine of the Gifts of the Holy Spirit, i.e., knowledge, wisdom, spirit, faith, healing, miracles, prophecy, speaking in tongues and interpreting what another says when he speaks in tongues.

Specifically, Corinthian Glossolalia was an activity of the Holy Spirit coming upon a person and compelling him to external expressions directed to God, but not understood by others. In Pentecost Glossolalia, while speaking in several different tongues, both the speaker and the listener understood what was uttered. The Glossolalia manifested in Corinth was the utterance of words, phrases, sentences, etc., intelligible to God but not to the person uttering them. What was uttered needed to be interpreted by another who had the gift of interpretation.

When the person spoke, his soul became passive and his understanding became inactive. He was in a state of ecstasy. While the words or sounds were prayer and praise, they were not clear in meaning and gave the impression of something mysterious. The phenomenon included sighs, groanings, shoutings, cries and utterances of disconnected speech, sometimes jubilant and some times ecstatic. There is no question-the Church of Corinth had Glossolalia; St. Paul attests to that and makes mention of it. But he also cautions the Corinthian Christians about excessive use; especially to the exclusion of the other more important gifts.

It appears St. Paul was questioned about the working of the Holy Spirit through the Gifts. Corinth was greatly influenced by Greek paganism which included demonstrations, frenzies and orgies, all intricately interwoven into their religious practices. In post Homeric times, the cult of the Dionysiac orgies made their entrance into the Greek world. According to this, music, the whirling dance, intoxication and utterances had the power to make men divine; to produce a condition in which the normal state was left behind and the inspired person perceived what was external to himself and the senses.

In other words, the soul was supposed to leave the body, hence the word ecstasy (ek stasis). They believed that while the being was absent from the body, the soul was united with the deity. At such times, the ecstatic person had no consciousness of his own.

The Corinthians of Paul's time were living under the influence of Dionysiac religious customs. It was natural that they would find certain similarities more familiar and appealing. Thus the Corinthians began to put more stress on certain gifts like glossolalia. No doubt the Apostle was concerned that their ties and memories of the old life should be reason enough to regulate the employment of Glossolalia. In chapter 14, he says:

"I would like for all of you to speak in strange tongues; but I would rather that you had the gift of proclaiming God's message. For the person who proclaims God's message is of greater value than the one who speaks in strange tongues-unless there is someone who can explain what he says, so the whole Church may be edified. So when I come to you, my brethren, what use will I be to you if I speak in strange tongues? Not a bit, unless I bring to you some revelation from God or some knowledge or some inspired message or some teaching."

Apostolic times were a unique period, rich with extraordinary and supernatural phenomena, for the history of mankind. The Lord God set out to make new creations through the saving grace of His Son, and implemented into perfection through the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit endowed men and women with many gifts in order to bring this about. One of its gifts during New Testament times was Glossolalia. But even from New Testament times, it would seem Glossolalia began to phase out. St. Paul, it seems, indicates later in chapter 14 that Glossolalia should be minimized and understood preaching, maximized. Justin Martyr, a prolific mid-century writer lists several kinds of gifts but does not mention Glossolalia. Chrysostom wrote numerous homilies on Books of the New Testament during the fourth century but does not appear to make mention of Glossolalia as noted in First Corinthians.