THE CELEBRATION OF EASTER IN EAST AND WEST: A sermon by St John Chrysostom, followed by a sermon by Cardinal Ratzinger during the Vigil of 2005. This followed by Fr Louis Bouyer on the Vigil, Father Alexander Schmemann, the Orthodox liturgist, and Father Stephen Freeman, also Orthodox, on Easter. Towards the end, there are two videos by N.T. Wright, Anglican biblical scholar and ex-Bishop of Durham, on the importance of the Resurrection. Also more videos with Easter liturgical music and celebration. Material will be added to this post as it arrives.

The Catechetical Sermon of St. John Chrysostom is read during Matins of Pascha.

If any man be devout and love God, let him enjoy this fair and radiant triumphal feast. If any man be a wise servant, let him rejoicing enter into the joy of his Lord. If any have labored long in fasting, let him now receive his recompense. If any have wrought from the first hour, let him today receive his just reward. If any have come at the third hour, let him with thankfulness keep the feast. If any have arrived at the sixth hour, let him have no misgivings; because he shall in nowise be deprived thereof. If any have delayed until the ninth hour, let him draw near, fearing nothing. If any have tarried even until the eleventh hour, let him, also, be not alarmed at his tardiness; for the Lord, who is jealous of his honor, will accept the last even as the first; he gives rest unto him who comes at the eleventh hour, even as unto him who has wrought from the first hour.

And he shows mercy upon the last, and cares for the first; and to the one he gives, and upon the other he bestows gifts. And he both accepts the deeds, and welcomes the intention, and honors the acts and praises the offering. Wherefore, enter you all into the joy of your Lord; and receive your reward, both the first, and likewise the second. You rich and poor together, hold high festival. You sober and you heedless, honor the day. Rejoice today, both you who have fasted and you who have disregarded the fast. The table is full-laden; feast ye all sumptuously. The calf is fatted; let no one go hungry away.

Enjoy ye all the feast of faith: Receive ye all the riches of loving-kindness. let no one bewail his poverty, for the universal kingdom has been revealed. Let no one weep for his iniquities, for pardon has shown forth from the grave. Let no one fear death, for the Savior’s death has set us free. He that was held prisoner of it has annihilated it. By descending into Hell, He made Hell captive. He embittered it when it tasted of His flesh. And Isaiah, foretelling this, did cry: Hell, said he, was embittered, when it encountered Thee in the lower regions. It was embittered, for it was abolished. It was embittered, for it was mocked. It was embittered, for it was slain. It was embittered, for it was overthrown. It was embittered, for it was fettered in chains. It took a body, and met God face to face. It took earth, and encountered Heaven. It took that which was seen, and fell upon the unseen.

O Death, where is your sting? O Hell, where is your victory? Christ is risen, and you are overthrown. Christ is risen, and the demons are fallen. Christ is risen, and the angels rejoice. Christ is risen, and life reigns. Christ is risen, and not one dead remains in the grave. For Christ, being risen from the dead, is become the first fruits of those who have fallen asleep. To Him be glory and dominion unto ages of ages. Amen.

About St. John Chrysostom:

St. John Chrysostom ("The Golden Tongue") was born at Antioch in about the year 347 into the family of a military-commander, spent his early years studying under the finest philosophers and rhetoricians and was ordained a deacon in the year 381 by the bishop of Antioch Saint Meletios. In 386 St. John was ordained a priest by the bishop of Antioch, Flavian.

Over time, his fame as a holy preacher grew, and in the year 397 with the demise of Archbishop Nektarios of Constantinople—successor to Sainted Gregory the Theologian—Saint John Chrysostom was summoned from Antioch for to be the new Archbishop of Constantinople.

Exiled in 404 and after a long illness because of the exile, he was transferred to Pitius in Abkhazia where he received the Holy Eucharist, and said, "Glory to God for everything!", falling asleep in the Lord on 14 September 407.

HOMILY OF CARD. JOSEPH RATZINGER

Altar of the Confessio in St Peter's Basilica

Holy Saturday, 26 March 2005

The liturgy of the holy night of Easter - after the blessing of the paschal candle - begins with a procession behind the light and towards the light. This procession symbolically sums up the entire catechumenal and penitential journey of Lent, but also calls to mind Israel's long journey through the desert towards the Promised Land, and lastly, it symbolizes the journey of humanity, which in the night of history was seeking light, seeking paradise, seeking true life, reconciliation between the peoples, between heaven and earth, universal peace.

Thus, the procession involves the whole of history, as the words of the blessing of the paschal candle proclaim: "Christ yesterday and today. The beginning and the end.... All time belongs to him. To him be glory and power through every age for ever...".

But the liturgy does not founder in general ideas; it is not content with vague utopias, but offers us very concrete instructions about the way to take and the destination of our journey.

Israel was guided in the desert at night by a column of fire and during the day by a cloud. Our column of fire, our sacred cloud, is the Risen Christ, symbolized by the lighted paschal candle.

Christ is light; Christ is the way, the truth, and the life; in following Christ, by keeping our hearts' gaze fixed on Christ, we find the right way. The whole pedagogy of the Lenten liturgy makes this fundamental imperative concrete.

Following Christ means first of all being attentive to his words. Participation in the Sunday liturgy week after week is necessary for every Christian, precisely to enable the person to be truly familiar with the divine word; the human being does not live on bread alone, nor on money or career; we live on the Word of God that corrects us, renews us, shows us the true structural values of the world and of society: God's Word is the true manna, the bread from heaven that teaches us life and how to be properly human.

Following Christ entails being attentive to his commandments - summed up in the twofold commandment to love God and our neighbour as ourselves. Following Christ means having compassion on the suffering, of having a heart for the poor; it also means having the courage to defend the faith against ideologies; it means trusting in the Church and in her interpretation and concretization of the divine word for our current circumstances.

Following Christ means loving his Church, his Mystical Body. By moving in this direction we light tiny lights in this world, we dispel the darkness of history.

Israel was journeying to the Promised Land. The whole of humanity is seeking something like the Promised Land. The Easter liturgy is very specific on this point. Its goals are the sacraments of Christian initiation: Baptism, Confirmation, the Holy Eucharist.

The Church thus tells us that these sacraments are the anticipation of the new world, its presence anticipated in our lives.

In the ancient Church the Catechumenate was a journey step by step to Baptism: a journey of the opening of the senses, heart and mind to God, the learning of a new lifestyle, a transformation of personal existence into growing friendship with Christ in the company of all believers.

Thus, after the various stages of purification, openness and new awareness, the sacramental act of Baptism was the definitive gift of new life. It was a death and resurrection, as St Paul says in a sort of spiritual autobiography: "I have been crucified with Christ; it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me, and the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me" (Gal 2: 20).

The Resurrection of Christ is not merely the memory of a past event. On Easter night, in the sacrament of Baptism, resurrection, the victory over death, is truly achieved.

Therefore, Jesus said: "[H]e who hears my word and believes him who sent me, has eternal life... he... has passed from death to life" (Jn 5: 24). And on the same topic he told Martha, "I am the resurrection and the life..." (Jn 11: 25). Jesus is the Resurrection and eternal life; to the extent that we are united with Christ we have today "passed from death to life", we are already living eternal life, which is not only a reality that comes after death but also begins today, in our communion with Christ.

Passing from death to life: this, together with the sacrament of Baptism, is the real core of the liturgy of this holy night. Passing from death to life: this is the way by which Christ opened the door, the way the celebrations of the Easter festivities invite us to take.

Dear faithful, most of us received Baptism as children, unlike these five catechumens who are now preparing to receive it as adults. They are here ready to proclaim their faith in a loud voice.

But for most of us, it was our parents who anticipated our faith. They gave us biological life without being able to ask us whether or not we wanted to live, rightly convinced that it is good to be alive and that life is a gift.

They were equally convinced, however, that biological life is a fragile gift; indeed, in a world marked by so many evils, it is an ambiguous gift that becomes a true gift only if, at the same time, it is possible to administer the antidote to death, communion with invincible life, with Christ.

Together with the fragile gift of biological life our parents gave us the guarantee of true life in Baptism. It is now up to us to make this gift our own, entering more and more radically into the truth of our Baptism.

Every year the Easter Vigil invites us once again to immerse ourselves in the waters of Baptism, to pass from death to life, to become true Christians.

"Awake O sleeper, and arise from the dead, and Christ shall give you light", says an ancient baptismal hymn that St Paul cited in his Letter to the Ephesians (5: 14). "Awake, O sleeper... and Christ shall give you light", the Church says to all of us today. Let us awaken from our weary Christianity that lacks dynamism; let us stand and follow Christ the true light and the true life. Amen.

Why Keep Watch? Why Vigil for Easter?

(Excerpts from Fr. Louis Bouyer)

If Easter night is a Vigil…this is owed, above all, to the fact that it is the night of the Exodus, the night in which the people of Israel were freed from the yoke of the Egyptians and entered into the freedom of being the sons of God…Why then did Israel celebrate this nocturnal Vigil year after year? Why did she dress as a pilgrim? Why did she eat in a hurry like a traveller preparing to leave on a journey? Was all this only a theatrical commemoration, pleasant to imitate, or the revival of a past event? There is no shadow of a doubt that in the eyes of Israel, the Exodus was the most glorious event of her whole history. Israel was the people of God, and she knew this thanks only to the undeniable election that was the consequence of the intervention of God: an intervention which liberated the people from slavery and established them in the freedom of the sons of God.

For the people of Israel, therefore, the celebration of Pasch, the memorial of the Exodus, meant celebrating their own birth and consequently, reaffirming in their own consciousness that they were God’s chosen people, and that God was with them.

For us too the Vigil must be something more than simply a service of remembrance. It is not a theatrical performance aimed simply and solely at registering historical facts in the mind. In the first place, it is something real. We stay awake because we are waiting: because we are waiting for God to pass among us and because when He comes we want Him to find us ready for the wonderful exodus which he makes possible.

The Holy Vigil - Louis Bouyer

If we wish the restoration of the Paschal Office on Holy Saturday night to arise in the faithful something deeper and more positive than passing admiration, if we wish to grasp the deep sense of christian renewal inherent in the Paschal Vigil, we must be aware of certain conditions in the absence of which we could never come to understand what takes place on that holy night. Among these conditions there is one of utmost importance, which does not seem to have been realized; all the more reason then why we must insist on its importance. This condition involves nothing less than coming to understand, in all its depths, what a Vigil is and what it means: to be specific, the Paschal Vigil.

Many people who are enthusiastic about the new (but also very ancient) practice of having an all-night Vigil, will believe that they know exactly why the Paschal Vigil has been reinstated. However, they do not realize that the superficiality (not to speak of the childishness) of their response provides the clearest aspect of the excuse used by those who remain indifferent to this recent reform.

We have heard that Christ rose from the dead at midnight and that is why we celebrate the Paschal Vigil in the night.

This argument is undoubtedly of little value since we do not know, clearly or precisely, the circumstances of the event. The apparition of the angels, (not of the One who had risen) to the soldiers during the night, suggests that the resurrection had taken place on the evening of the previous day. The apparitions to the disciples, however, do not take place until the following day in the morning. If we were to comply with these circumstances of time, we ought rather to celebrate the Office in the evening, or the morning. It is curious to observe how this two-way celebration is amongst the suggestions of those who are unhappy with these liturgical reforms. If the view of the Paschal Vigil held by these inexpert apologists is taken as valid, it is very difficult not to reach one of these two conclusions. Our work must begin from this precise point, by trying to banish and eradicate, as thoroughly as possible, this way of thinking. Liturgical commemorations have nothing in common with this kind of sentimental superstition which assumes a sort of sympathetic magic (or magic sympathy) between a fact and the exact hour in which it occurred. Let us be honest, no one knows exactly when the resurrection took place. At the same time, there would be no sense at all in giving so much significance to a condition which in itself is not important. Let us be quite clear about it. The fact that the resurrection took place during the night, when the world was immersed in deep sleep, is a fact which has a certain symbolic value and of which the liturgy, quite rightly, makes the greatest possible use. But this again has nothing to do with the superstition attached to the hour X; as if the christian sabbath had something to do with the witches' sabbath which dawns at the first stroke of midnight.

Having overcome this misconception, how then should we be guided? In the first place it is necessary to discover the necessary relationship that exists between the Vigil and the waiting, the awaiting of the consummation of the christian mystery, that is to say, the parousia, the glorious return of the Saviour. We are then ready to understand why and in what sense the Vigil is so profoundly penetrated by what early christianity calls the "consolation of the Scriptures". Ultimately, we shall examine the specific nature of the Paschal Vigil regarding its aspect as the Vigil of initiation, in as much as it is a preparation for the Paschal Sacrament, specifically of initiation into Baptism, or the renewal of initiation in the most solemn communion of the year.

1. The first point which needs to be clarified is that the Paschal Vigil is not a kind of impressive "Midnight Mass". It is a sacred celebration lasting the whole night long, from the setting of the sun to its rising. If it were possible to celebrate it in its entirety, we should begin "when the lamps are lit" and not end it until the first light of day dawns. It begins in fact, with the Lucernarium followed by the blessing of the lamps by which watch is kept all through the night. The Vigil should last until the moment in which the dawn breaks, making it necessary to put aside the now useless lamps, that had been lit the previous day at dusk.

The meaning of this ceremony is to be found in its origins, since its institution took place long before the primitive christian comnunities. This is proven by the fact that the Paschal night, that is the Vigil which takes place during it, was celebrated long before it was transformed into a night of resurrection. To this day, the rites which take place during that night and the readings taken as the theme for meditation, have their origin in this pre-christian Vigil. If Easter night is a Vigil, that is a night in which we do not sleep, this is owed, above all, to the fact that it is the night of the Exodus, the night in which the people of Israel were freed from the yoke of the Egyptians and entered into the freedom of being the sons of God. This was the night in which the same God "passed" among them to give them freedom, dragging their oppressors to their death. The Paschal name originates in this double "passage of God" which kept Israel on the alert as a prisoner in the land of Ham.

Why then did Israel celebrate this nocturnal Vigil year after year? Why did she dress as a pilgrim? Why did she eat in a hurry like a traveller preparing to leave on a journey? Was all this only a theatrical commemoration, pleasant to imitate, or the revival of a past event? There is no shadow of a doubt that in the eyes of Israel, the Exodus was the most glorious event of her whole history. Israel was the people of God, and she knew this thanks only to the undeniable election that was the consequence of the intervention of God: an intervention which liberated the people from slavery and established them in the freedom of the sons of God.

For the people of Israel, therefore, the celebration of Pasch, the memorial of the Exodus, meant celebrating their own birth and consequently, reaffirming in their own consciousness that they were God's chosen people, and that God was with them.

In reality the object of this recurring celebration was something very different from being a mere, if pleasing, recollection of an ancient event and its everlasting consequences. If once again they were ready to begin a way, if once again they were to eat in a hurry, if they were to pass the night in vigil, it was only because the ancient exodus compelled them to keep their hope fixed on another exodus. The fact that God had intervened on that occasion, the fact that He had passed among His people marking them with an indelible blessing, was of importance above all because it was the promise of a new, much more glorious, much more decisive intervention. God will return again to pass among his people. He will return again to manifest himself "with strong hand and arm outstretched", and His people, strengthened by means of this new election - just as in the first Exodus - will pass from slavery to freedom, from darkness to light, from death to life. It might be said that the mission of prophecy from the eighth to the sixth century, and that of the countless tragic events in which the chosen people partook, from the capture of Jerusalem to its final destruction, had the sole objective of arousing this expectancy in the people (of that time). But no, not at all: However great the past might be, it was not in it but in the future that the religious ideal had to be anchored. That first people of God were not to be the last people of God. The reason for all the trials that had to be borne was precisely this. These were not signs of total abandon on God's part, but whirlwinds announcing the immortal creation that was to occur later. The past, however great and wonderful it might have been, was no more than a sketch of what was to come. The ransoms of the time were not even a shadow compared to those which were later to take place. God would again appear amongst His own people, and take them with Him, He would lead them out of the kingdom of Satan for ever, from sin and death, and He would establish them in His own kingdom where Israel would live for ever in the light of His countenance. Because of this sense of expectation during the Paschal night no one slept. It was essential to keep watch. "If You would only leave the heavens and come down" : This was the cry of the prayer in the night.

Having been prepared to enter into the eternal kingdom, in which He who was the only faithful "servant' would appear, dragging with Him in His exodus the whole nation, the elect remnant of ancient Israel lived in the imminent expectancy of this Pasch, which would not be a memory but the real Pasch, the only really true Pasch, because the other was no more than a shadow of the one that was to come.

The way in which Israel celebrates the Passover during the night, and the way Christ lived this with His own chosen ones for the last time on that supreme night, is still,with very simple modifications, the same Pasch as that of the christians. There is in our past also a Passover and an Exodus which we must commemorate. For us too the Vigil must be something more than simply a service of remembrance. It is not a theatrical performance aimed simply and solely at registering historical facts in the mind. In the first place, it is something real. We stay awake because we are waiting: because we are waiting for God to pass among us and because when He comes we want Him to find us ready for the wonderful exodus which he makes possible. The memory of that other Pasch, of that other exodus, holds no other value for us than as a pledge and image of what we are waiting for. God has been among us; He has made Himself present through Christ. But we are not tied to this two-thousand year-old memory, because He arouses in us the jubilant expectation of His imminent return. When, according to the promises made by the angels on Ascension Day, Christ appears again in full glory, there where He left us, to establish us once and for all with Him so that God is all in all, we shall abandon the earth where we have lived as exiles, the country in which we have been subjected to slavery, the world in which we feel like pilgrims and travellers who cannot even rest the night since they have no place to lay their heads. We shall leave it to enter, once and for all, our own land, in the Father's house: that place where He has gone before us, He who willed himself to be the first born for us, where He has gone to prepare a place and from which we are waiting for Him to come, expecting Him from one moment to the next to take us with Him so that we can possess Him eternally.

When we come to understand all this, we become aware that the Paschal Vigil is something much richer than just a living picture which is more or less commemorative, instructive and edifying. To put it bluntly, the Paschal Vigil has nothing to do with a pious theatrical performance. It is the night in which we do at least once a year, what we should always do and what, spiritually we should be doing at every moment. We deprive ourselves of sleep, of rest, we keep a constant vigil, because if we are christians, and if being christian means something, we are waiting, we must await the final coming, the coming which all those who have preceded us invite us to wait for. "Israel, be ready to meet your God." These words are directed to us with all the power and wisdom that could ever have been directed to anyone.

This expectancy occurs during the night since divine wisdom traces out and prepares its plans in the darkness of faith, plans that without faith man cannot know through his foolish wisdom. This waiting takes place in the night, because it is the waiting for the day, that day par excellence which the Bible calls the Day of Yahweh, THE day, nothing more. The dawn which we await will be a dawn after which no sun will set because we shall pass, on a journey with no return, from time to eternity. All these things tell us how important the attitude of expectancy which the Paschal Vigil seeks to arouse is for the christian faith. This attitude must predominate, in a permanent way, over our whole lives. The Church very soon passed from the annual to the weekly celebration of Easter, the Sunday Easter, with the precise intention of keeping this sense of Paschal waiting alive and throbbing.

Later, at the beginning of the fourth century, the aesthetics felt that christianity had become lethargic, too complacently set in the world to await anything else to happen, and so they instituted the daily vigil. This has been preserved by all contemplative orders and has also been maintained, in symbolic form, in the recitation of the Divine Office.

The Paschal Vigil continued as, and must without doubt become again, the great annual occasion in which the whole Church is united, moved by the memory of the previous times of waiting, to await the last and final passing of God. On Easter night the Church expressed in a physical manner what she should always be doing spiritually: she is like a wife who stays awake because her husband has left her for a moment and she cannot go to sleep again until he reappears, bringing with him the new day which will be the beginning of an eternal springtime. Awake, my friend, my bride, awake and come with me.

(c) Fr. Pius Sammut, OCD. Permission is hereby granted for any non-commercial use, provided that the content is unaltered from its original state, if this copyright notice is included.

Fr Schmemann on Easter and the Resurrection

Father Alexander Schmemann (1921-1983) was educated in France before moving to the United States in 1951, where he quickly gained recognition as a dynamic and articulate spokesman for Orthodoxy. He was for many years Dean and Professor of Liturgical Theology at St. Vladimir’s Orthodox Seminary in New York. Through his lectures on college campuses, his regular radio broadcasts to Eastern Europe, and his books, now translated into eleven languages, he brought the Faith to an ever-growing audience. The following paragraphs are from his book Great Lent - Journey to Pascha, published in 1969:

It is necessary to explain that Easter is much more than one of the feasts, more than a yearly commemoration of a past event? Anyone who has, be it only once, taken part in that night which is “brighter than the day,” who has tasted of that unique joy knows it. But what is that joy about? Why we can sing, as we do, during the Paschal liturgy: “today are all things filled with light, heaven and earth and places under the earth”? In what sense do we celebrate, as we claim we do, “the death of Death, the annihilation of Hell, the beginning of a new life and everlasting . . .”? To all these questions, the answer is: the new life which almost two thousand years ago shone forth from the grave, has been given to us, to all those who believe in Christ. And it was given to us on the day of our Baptism, in which, as St. Paul says, we “were buried with Christ...unto death, so that as Christ was raised from the dead we also may walk in newness of life” (Rom. 6:4). Thus, on Easter we celebrate Christ’s Resurrection as something that happened and still happens to us . . . That is why, at the end of the Paschal Matins, we say: “Christ is risen and not one dead remains in the grave!”

. . . It is not our daily experience, however, that this faith is very seldom ours, that all the time we lose and betray the “new life” which we received as a gift, and that, in fact, we live as if Christ did not rise from the dead, as if that unique event had no meaning whatsoever for us? . . . We manage to forget even the death and them, all of a sudden, in the midst of our “enjoying life” it comes to us: horrible, inescapable, senseless. We may from time to time acknowledge and confess our various “sins”, yet we cease to refer our life to that new life which Christ revealed and gave to us; Indeed, we live as if he never came. This is the only sin, the sin of all sins, the bottomless sadness and tragedy of our nominal Christianity.

If we realize this, then we may undrestand what Easter is . . . and understand that the liturgical traditions of the Church, all its cycles and services, exist, first of all, in order to help us recover the vision and the taste of that new life which we so easily lose and betray, so that we may repent and return to it . . . It is the worship of the Church that was from the very beginning and still is our entrance into, our communion with, the new life of the Kingdom. It is through her liturgical life that the Church reveals to us something of that which “the ear has not heard, the eye has not seen and what has not yet entered the heart of man but what God has prepared for those who love Him.” And in the center of that liturgical life, as its heart and climax, as the sun whose rays penetrate everywhere, stands Pascha. It is the door opened every year into the splendour of Christ’s Kingdom, the foretaste of the eternal joy that awaits us, the glory of the victory which already, although invisibly, fills the whole creation: “death is no more!”

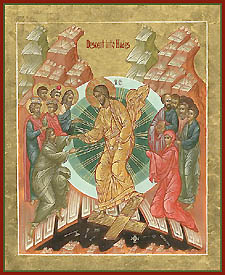

KNOCKING DOWN THE GATES OF HELL

The Swedish Lutheran theologian, Gustav Aulen, published a seminal work on types of atonement theory in 1930 (Christus Victor). Though time and critique have suggested many subtler treatments of the question, no one has really improved on his insight. Especially valuable was description of the “Classic View” of the atonement. This imagery, very dominant in the writings of the early Fathers and in the liturgical life of the Eastern Church, focused on the atonement as an act of invasion, smashing of gates and bonds, and the setting free of those bound in hell. Aulen clearly preferred this imagery and is greatly responsible for its growing popularity in some segments of Western Christendom.

The language was obscured in the West by the later popularity of propitiatory suffering (and the various theories surrounding it). Aulen noted, however, that Luther tended to prefer this older imagery. I had opportunity to do a research paper in grad school on the topic. I surveyed all of the hundreds of hymns written by Luther and analyzed them for their atonement theology. All but about two used the Classic View. Aulen was right.

In Orthodoxy, this imagery is the coin of the realm in the hymns surrounding Pascha. All of Holy Week is predicated on the notion of Christ descent into hell and radical actions of destroying death and setting free those held in captivity. St. John Chrysostom’s great Paschal Homily, read in every Orthodox Church on the night of Pascha, is an “alley, alley, in come free!” of salvation.

I have written on this topic before. I thought, however, to share some of the verses from the hymns for the Matins of Holy Saturday. Their language is a pure expression of the spirit of Orthodox Pascha and the atonement teaching of the Fathers.

Hell, who had filled all men with fear,

Trembled at the sight of Thee,

And in haste he yielded up his prisoners,

O Immortal Sun of Glory

Thou hast destroyed the palaces of hell by Thy Burial, O Christ.

Thou hast trampled death down by thy death, O Lord,

And redeemed earth’s children from corruption.

Though thou art buried in a grave, O Christ,

Though Thou goest down to hell, O Savior,

Thou hast stripped hell naked, emptying its graves.

Death seized Thee, O Jesus,

And was strangled in Thy trap.

He’’s gates were smashed, the fallen were set free,

And carried from beneath the earth on high.

O Savior, death’s corruption

Could not touch thy holy flesh.

Thou hast bound the ancient murdered of man,

And restored all the dead to new life.

Thou didst will, O Savior,

To go beneath the earth.

Thou didst free death’s fallen captives from their chains,

Leading them from earth to heaven.

In the earth’s dark bosom

The Grain of Wheat is laid.

By its death, it shall bring forth abundant fruit:

Adam’s sons, freed from the chains of death.

Wishing to save Adam,

Thou didst come down to earth.

Not finding him on earth, O Master,

Thou didst descend to Hades seeking him.

O my Life, my Savior,

Dwelling with the dead in death,

Thou hast destroyed the iron bars of hell,

And hast risen from corruption.

These examples could be multiplied many times over. The section of Matins from which these are taken has over 100 verses! Orthodox Holy Week and Pascha has many ways of acting out this theology. Lights go up at the hint of victory, particularly as we sing the Song of Moses celebrating the drowning of Pharaoh’s army. In some parishes, bay leaves are tossed in the air by the priest in a fairly violent and joyous celebration of the victory. In yet others, at certain points during the Vesperal Liturgy of Pascha, loud noises such as the banging of pots and pans are heard as the liturgy describes the smashing of hell’s gates. There’s is one village in Greece where two parishes have developed a custom of firing rocker fireworks at each other in the Paschal celebration.

Such antics completely puzzle the non-Orthodox and even seem comical. The Paschal celebration in Orthodoxy is far more akin to the wild street scenes in American cities when the end of World War II was announced – and for the same reason!

All of this also explains why many Orthodox are very reluctant to engage in “who’s going to hell” discussions with other Christians (though some Orthodox sadly seem to relish the topic). The services of Holy Week, as illustrated in these verses, are filled with references to hell. I daresay that no services elsewhere in all of Christendom make such frequent mention of hell. But the language is just as illustrated above. It’s all about smashing, destruction and freedom. It is the grammar of Pascha. It should be the grammar of Christianity itself.

Hell is real. Jesus has come to smash it. It is the Lord’s Pascha. It is time to sing and dance.

Orthodoxy and the Resurrection

why does Jesus' Resurrection matter?

N. T. Wright

FIRE FROM THE TOMB OF CHRIST

Descent of the Holy Fire in the Church of the Sepulcher. Year: 2017 Holy Assumption Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra Holy Assumption Kyiv-Pechersk Lavra

Holy Fire to be delivered to America for first time

“The Holy Fire, which descends every year on the eve of the Orthodox feast of Pascha in Jerusalem, will be delivered to the various corners of the Earth, with the support of the Russian St. Andrew the First-Called Foundation, including, for the first time this year, to the United States of America.

“It is planned to deliver this sacred blessing for the first time to the US, and we’ve already received permission to transport the lampadas with the Holy Fire on board a plane,” the foundation’s press service reported to Interfax-Religion today. The Holy Fire is being brought to the US by the initiative of parishioners of the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia.”

ABBOT PAUL'S HOMILIES

FOR PASCHA

FOR PASCHA

Holy Saturday 2017

I have always listened to Prayer for the Day at 5.43 each morning on Radio Four, just before Farming Today. This morning the speaker was Bishop Angaelos, the Coptic Orthodox Bishop for the United Kingdom. I was so moved by his words that I’ve set aside the homily I prepared for this evening and will read you his short talk instead. I hope you will forgive me, but what has saddened me most, ever since the Iraq war began, is the annihilation of ancient Christian communities and churches in the Middle East and North Africa. The blame rests, in part, on our shoulders. This goes back, of course, to the break up of the Ottoman Empire a hundred years’ ago.

Bishop Angaelos said:

Bishop Angaelos

Coptic Bishop in Great Britain

“The celebration of Easter tends to bring its own set of challenges to Christians across the world, who face religious persecution on a daily basis. Most recently, our own Coptic Orthodox community in Egypt suffered brutal terrorist attacks that robbed families of loved ones, and shocked communities as a result of senseless and indiscriminate violence.

Terrorist attacks like these leave us questioning how humanity can reach a stage, when the value and sanctity of life is lost entirely. They can lead us to feel afraid or hopeless, if not also bitter and angry.

Yet, on this eve of Easter Sunday we remember that, although our journey is often characterised by suffering and challenge, the Resurrection of Jesus Christ promises victory over evil and a conquering of death itself.

When I look at the peaceful reaction of my brothers and sisters in Egypt, who face on going terror, I am humbled by their example of determined faith and Christian witness. Many, who were subject to the recent attacks on churches during a time of prayer, have already chosen to return to their churches to pray as families. That, to me, demonstrates the true power of the Risen Lord in our lives today, that we need never again fear death, but see it as a new beginning and entry point to a glorious life to come.

Lord, we pray for the safety of our brothers and sisters in Egypt and for all Christian communities, who are facing constant provocation and attempts to move them to violence and division. May your peace continually reign in our hearts. Amen.

Dear brothers and sisters, may our celebration of the Resurrection this Easter renew our faith in the Risen Christ and strengthen our desire to live in the power of his Spirit, ever bearing witness to the peace and joy of God’s Kingdom, even in our suffering and pain. On behalf of Fr Prior and the monastic community, I wish you all a very happy Easter. Christ is risen; he is risen indeed. Alleluia.

Easter Sunday 2017

“They have taken the Lord out of the tomb and we don’t know where they have put him.” These are the words addressed by Mary of Magdala to “Simon Peter and the other disciple, the one Jesus loved,” in St John’s account of the discovery of the empty tomb that first Easter morning. The details of the Resurrection we find here are fascinating. To begin with, Mary Magdalene is alone and not with the other women, as the other three gospels relate, and when she goes to the tomb on the first day of the week, it’s still dark, yet she sees that the stone has been moved away. She runs off and finds Peter and the Beloved Disciple, who hadn’t been anywhere near the tomb since Jesus was buried. Why does she say, ”they have taken the Lord out of the tomb,” and, if she was alone, why does she say, “we don’t know where they have put him”? Details, but important ones, for it’s the Resurrection of Jesus that John is writing about, the most life-transforming event since the beginning of time, one that changed our vision of suffering and death for ever.

At this stage Mary hasn’t seen the angel, nor has she looked inside the tomb, something she will do later when she returns to the garden. Only Peter and the other disciple go into the empty tomb and see the linen cloths lying on the ground. Mary fears that the body has been removed or stolen: why else would the stone have been moved away? But why does she speak of herself as “we”? She is the first to see that the tomb has been disturbed, so perhaps speaks in the name of the whole community of disciples. How true that traditional title given to her, apostola apostolorum, the Apostle to the apostles! Later, she will be the first to see Jesus risen from the dead and speak with him, though to begin with she takes him for the gardener. She will be the first to tell the world, “I have seen the Lord.”

Now the Fourth Gospel has an important theme throughout: personal encounter with Jesus that leads to faith. Think of the Samaritan woman at Jacob’s Well or of Nicodemus, who visits Jesus by night; think of his close friendship with Mary, Martha and Lazarus or of that special relationship with the disciple he loved, the one who stood at the foot of the cross with Mary his mother and now runs faster than Simon Peter and, looking into the tomb, is the first to believe in the Resurrection. Think of Thomas, doubting Thomas, who could not believe the word of his fellow disciples, yet when he sees Jesus face to face a week later, gets on his knees and exclaims, “My Lord and my God.” It takes time and a personal encounter with Jesus to believe. All these were really encounters with the Risen Christ, for the gospel was written in the light of the Resurrection, and to help us believe “that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that through believing you may have life in his name.”

All of us here this morning have come to celebrate Easter because we too have had a personal encounter with the Risen Christ and the experience of his love and friendship. As a result of that encounter, each one of us has a special, intimate and unique relationship with him, a friendship that no one else has, a friendship that strengthens our faith and supports our weakness, even when the going gets hard and we are tempted to doubt. The great thing about Jesus is that he meets us where we are; he comes towards us on the road of life, not to judge but to forgive, not to condemn but to save.

St Paul wrote to the Romans, “If we have been united with him in a death like his, we will certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his. If we have died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him.” The prayer of the Belmont Community today is that you all come to share in the life of Risen Christ, our hope and our salvation. Amen.

No comments:

Post a Comment