In this post I shall attempt to express the attitudes, ideas, difficulties and theological positions of some of those on both sides of the Orthodox-Catholic divide who take part in the ecumenical dialogue. This is not meant to be a polemical essay; hence, I shall not be dealing with the Orthodox anti-ecumenical opposition.

We shall start with a short homily of Kirill, Patriarch of Moscow:

A SUMMARY

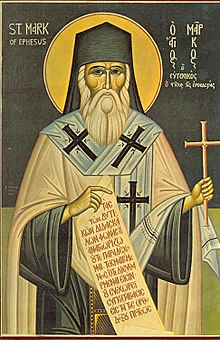

The Patriarch begins by saying that he was enthroned on the feast of St Mark of Ephesus who was the only bishop not to sign with the other Orthodox bishops at the Council of Ferrara-Florence (1438-9). The Byzantine emperor wanted western military help to protect Constantinople from the Moors, and thus sought the help of the pope. According to Patriarch Kirill, St Mark said:

union must not be motivated by fear;

union cannot take place motivated by mere pragmatism;

and, most importantly, union cannot take place in such a way as to bring about schism. This council crushed the unity of the Orthodox world.

I was consecrated bishop on the feast of the Victory of Orthodoxy and was enthroned on the feast of St Mark of Ephesus. I cannot see this as mere coincidence. I am here to protect the purity of the Orthodox faith and to oppose any heresy or shame.

Before commenting on this, I think it would be a good idea to read some passages from the brilliant essay by the Orthodox theologian David Bentley Hart called "The Myth of Schism":

...That said, doctrines do divide us, and I think that, in the nature of things, the Eastern church inevitably has a keener sense of this. I have among my Roman Catholic theologian friends, especially those who have had little direct dealings with Eastern Christianity, some who are justifiably offended by the hostility with which the advances of the Roman Church are occasionally met by certain Orthodox, and who assume that the greatest obstacle to reunion of the churches is Eastern immaturity and divisiveness. The problem is dismissed as one of ‘psychology’, and the only counsel offered one of ‘patience’. Fair enough: decades of communist tyranny set atop centuries of other, far more invincible tyrannies have effectively shattered the Orthodox world into a contentious confederacy of national churches struggling to preserve their own regional identities against every ‘alien’ influence, and under such conditions only the most obdurate stock survives.

But psychology is the least of our problems. Simply said, a Catholic who looks eastward should find nothing to which to object, because what he sees is the Church of the Seven Oecumenical Councils (but—here’s the rub—for him, this means the first seven of twenty-one, at least according to the definition of Oecumenical Council bequeathed the Roman Church by Robert Bellarmine).

When an Orthodox Christian turns his eyes westward, however, he sees many elements that appear novel to him: the filioque clause, the way in which papal primacy is articulated, Purgatory, etc. Our divisions do truly concern doctrine, and this problem admits of no immediately obvious remedy, because both churches are so fearfully burdened by infallibility. And we need to appreciate that this creates an essential asymmetry in the Orthodox and Catholic approaches to the ecumenical enterprise.

No Catholic properly conscious of the teachings of his Church would be alarmed by what the Orthodox Church would bring into his communion—he would find it sound and familiar, and would not therefore suspect for a moment that reunion had in any way compromised or diluted his Catholicism. But to an Orthodox Christian, inasmuch as the Roman Church does make doctrinal assertions absent from his tradition, it may well seem that to accept reunion with Rome would mean becoming a Roman Catholic, and so ceasing to be Orthodox. Hence it would be unreasonable to expect the Eastern and Western churches to approach ecumenism from the same vantage: the historical situations of the churches are simply too different.

For David Bentley Hart, when we look at the differences between Catholic and Orthodox theology, simply as theology, they are not absolute differences. Some are due to differences of vocabulary, some are complementary, while, with others, we can simply allow the two theologies to correct one another.

The problem is dogma, not dogma in general, but all the Catholic dogmas defined after the split.. Dogmas do not drop down, ready made, from heaven. They belong to a process of gradual articulation and refinement and the need to formulate them arises in a particular intellectual and historic environment. However, Orthodoxy and Catholicism have developed in very different environments, have had different experiences, and have had to solve different problems. Hence there are Catholic dogmas that have no place in Orthodox tradition. To accept them, an Orthodox has to go outside his tradition into someone else's. This implies that their Tradition is somehow defective and that reunion means "becoming Roman Catholic"; and this they don't accept. On the contrary, they consider their own church to be the "One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church" listed in the Nicene Creed. Hence this short sermon by Patriarch Kirill:

This sermon states the Orthodox doctrine that it is the Catholic Church, and he opposes it to modern liberalism which believes that one Christian church or community is as good as another. With a little adaptation, we would, of course, agree with the Patriarch.

Is there any possibility of union when both the Catholic Church and the Orthodox Church each claims to be "the one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church of the Creed? Is there any possibility of union when the Catholic Church has dogmas that the Orthodox cannot accept? Is there no alternative to the choice between the anti-ecumenists like Father Peter Heers and wishy-washy Anglican liberals?

MAKING A POSITIVE CASE FOR ECUMENISM

With St Mark of Ephesus and Patriarch Kirill, we must rule out any reunion based on fear or on mere pragmatism and apostolic efficiency, or in such a way that it will breed more schism. I suggest that, for the Patriarch of Moscow, the latter danger is greatest. I suspect that he is afraid that the Orthodox-Catholic dialogue may reach agreement before the Orthodox Church is ready for it. An agreement too soon could well cause schism. Indeed, there are Orthodox bishops who leave the Patriarch of Constantinople out of the dyptichs in the Liturgy because he is infected with "the ecumenical heresy"! Better, that Catholics and Orthodox work together on tasks that are uncontroversial, and get to know and love each other before agreement is reached.

We must remember that they have had no Vatican II; and that, before Vatican II, the ressourcement theologians in France, as well as their Orthodox counterparts, covered their ecumenical discussions with a discreet silence, because both church authorities believed ecumenism to be inspired by doctrinal indifferentism. I once asked a Russian Orthodox archimandrite (he was Welsh actually, but belonged to the R.O.C. and lived in Paris) why V. Lossky, who was so sublime and profound in his exposition of Orthodox theology was so downright silly when it came to Catholic theology. He gave me a wry smile and said, "Well, you see, Father David, he had to write passages like that because Orthodox theologians in Russia and other Orthodox countries suspected all the Orthodox in France of being infected with Romanism. If he didn't write passages highly critical of Catholicism, they wouldn't have taken him seriously as an Orthodox theologian." Vatican scholastic theologians were just as xenophobic.

What gives us hope for the future is the copernican revolution in our understanding of the Church which took place in Vatican II. In their dialogue over decades with the Orthodox Russian theologians of Sainte-Serge, the ressourcement theologians in France accepted from the Russians the idea of Eucharistic Ecclesiology. This explains, better than any other theological theory why the words of Father Lev Gillet are correct. Father Lev knew both Catholicism and Orthodoxy from the inside. He wrote:

The whole teaching of the Latin Fathers may be found in the East, just as the whole teaching of the Greek Fathers may be found in the West. Rome has given St. Jerome to Palestine. The East has given Cassian to the West and holds in special veneration that Roman of the Romans, Pope Gregory the Great. St. Basil would have acknowledged St. Benedict of Nursia as his brother and heir. St. Macrina would have found her sister in St Scholastica. St. Alexis the "man of God," "the poor man under the stairs," has been succeeded by the wandering beggar, St. Benedict Labre. St. Nicolas would have felt as very near to him the burning charity of St. Francis of Assisi and St. Vincent de Paul. St. Seraphim of Sarov would have seen the desert blooming under Father Charles de Foucauld's feet, and would have called St. Thérèse of Lisieux "my joy." (Fr Lev Gillet)

Eucharistic Ecclesiology tells us that where the Eucharist is, there is the Church in its fullness, because Catholicism in its fullness is Christ who is fully present in each eucharistic celebration. There is only one Eucharist, celebrated many times, in which the whole Mystery of Christ is celebrated as a present reality; and the local eucharistic community is the fullness of Catholicism made visible in one place. When I celebrate Mass, all other celebrants in whatever place or time in history concelebrate, and all participants participate with me and my local community.

The local eucharistic liturgical celebration is also the source of all the Church’s powers, as Sacrosanctum Concilium, the document of Vatican II on the Liturgy says. Hence Tradition arises out of the synergy between the Holy Spirit and the Church operating in the liturgy.

Tradition is not something that comes out of a central place like Rome or Byzantium, but is shaped in diverse ways by the spiritual traditions of different places, even though all versions have a common source in apostolic preaching, and all share in the mind of the same Christ. For these reasons, true Catholicism is a diversity in which it is possible to discover unity. The unity is constantly being discovered and strengthened by the practice of ecclesial love, the evidence of the presence of the Holy Spirit, except when ecclesial love gets swamped or obliterated by worldly concerns or diabolical pride or prejudice - the devil uses our limitations.

This process has not always been plain sailing. There is the case of the Assyrian Church of the East. They are in schism and are Nestorians. Applying the principles of Orthodox anti-ecumenist hardliners, they are a non-church, with sacraments that don't work. Yet they are the church of St Isaac the Syrian who is completely orthodox, who would have been a credit to Mount Athos, if history could be changed. At the time of the great councils, the Assyrian Church was culturally, politically and physically cut off from the Byzantine/Roman Church, speaking Aramaic rather than Greek, belonging to the Persian Empire rather than Byzantium, and placed by Persia where they could have no contact with their brethren in Roman Syria. No one invited them to the councils. They heard of and accepted the Council of Nicaea only 85 years after it was held. The Council of Ephesus was somewhat unscrupulously managed by the Church of Alexandria and left no wiggle room for the Church of Antioch, and hence for the Assyrians; and, while Chalcedon was meant to address the concern of both Alexandria and Antioch, it didn't satisfy either, because neither church had any means in their own languages of adequately distinguishing "nature" from "person". Hence, the Assyrians rejected both councils.

Nevertheless, Roman theologians went behind the different formulations and found this fundamental coherence in Christ between the classical Catholic/Orthodox definitions of Ephesus and Chalcedon, on the one hand, and the formulations of the Assyrian Church. The result was the Christological agreement signed by Pope John Paul II and Patriarch Mar Dinkha in November 1994.

Based on the teaching that the sources of Tradition are found in the liturgical life of churches founded on apostolic preaching which had their own formulations, and that among the diverse formulations their is an inner coherence because they all are insights into the mind of Christ, and that this coherence is expressed in concrete language, finding this inner coherence meant that the Assyrian Church has kept its apostolic Tradition intact. Thus, in 1991, the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity declared:

Father Emmanuel Clapsis of the Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology writes:

The local eucharistic liturgical celebration is also the source of all the Church’s powers, as Sacrosanctum Concilium, the document of Vatican II on the Liturgy says. Hence Tradition arises out of the synergy between the Holy Spirit and the Church operating in the liturgy.

Tradition is not something that comes out of a central place like Rome or Byzantium, but is shaped in diverse ways by the spiritual traditions of different places, even though all versions have a common source in apostolic preaching, and all share in the mind of the same Christ. For these reasons, true Catholicism is a diversity in which it is possible to discover unity. The unity is constantly being discovered and strengthened by the practice of ecclesial love, the evidence of the presence of the Holy Spirit, except when ecclesial love gets swamped or obliterated by worldly concerns or diabolical pride or prejudice - the devil uses our limitations.

This process has not always been plain sailing. There is the case of the Assyrian Church of the East. They are in schism and are Nestorians. Applying the principles of Orthodox anti-ecumenist hardliners, they are a non-church, with sacraments that don't work. Yet they are the church of St Isaac the Syrian who is completely orthodox, who would have been a credit to Mount Athos, if history could be changed. At the time of the great councils, the Assyrian Church was culturally, politically and physically cut off from the Byzantine/Roman Church, speaking Aramaic rather than Greek, belonging to the Persian Empire rather than Byzantium, and placed by Persia where they could have no contact with their brethren in Roman Syria. No one invited them to the councils. They heard of and accepted the Council of Nicaea only 85 years after it was held. The Council of Ephesus was somewhat unscrupulously managed by the Church of Alexandria and left no wiggle room for the Church of Antioch, and hence for the Assyrians; and, while Chalcedon was meant to address the concern of both Alexandria and Antioch, it didn't satisfy either, because neither church had any means in their own languages of adequately distinguishing "nature" from "person". Hence, the Assyrians rejected both councils.

Nevertheless, Roman theologians went behind the different formulations and found this fundamental coherence in Christ between the classical Catholic/Orthodox definitions of Ephesus and Chalcedon, on the one hand, and the formulations of the Assyrian Church. The result was the Christological agreement signed by Pope John Paul II and Patriarch Mar Dinkha in November 1994.

Based on the teaching that the sources of Tradition are found in the liturgical life of churches founded on apostolic preaching which had their own formulations, and that among the diverse formulations their is an inner coherence because they all are insights into the mind of Christ, and that this coherence is expressed in concrete language, finding this inner coherence meant that the Assyrian Church has kept its apostolic Tradition intact. Thus, in 1991, the Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity declared:

Secondly, the Catholic Church recognises the Assyrian Church of the East as a true particular Church, built upon orthodox faith and apostolic succession. The Assyrian Church of the East has also preserved full Eucharistic faith in the presence of our Lord under the species of bread and wine and in the sacrificial character of the Eucharist. In the Assyrian Church of the East, though not in full communion with the Catholic Church, are thus to be found "true sacraments, and above all, by apostolic succession, the priesthood and the Eucharist" (U.R., n. 15).

Father Emmanuel Clapsis of the Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology writes:

It would be impossible for us to reach any convergence on the significance of the bishop of Rome if our consultation were to begin with a comparison of classic Roman Catholic and Orthodox views of the papacy. Our common reflection on this issue must be situated in the common ecclesiology of communion that our respective churches have begun to share, especially after Vatican II.[30] In 1974 our consultation stated: "The Church is the communion of believers living in Jesus Christ with the Father. It has its origins and prototype in the Trinity in which there is both distinction of persons and unity based on love, not subordination."[31] It also affirmed that the eucharistic celebration "both proclaims the most profound realization of the Church and realizes what it proclaims in the measure that the community opens itself to the Spirit".[32] This kind of ecclesiology leads to an affirmation of the full catholicity of the local church ‑ provided it lives by the Spirit of God which makes it the living body of Christ in communion of love with other local churches that share the same faith and life pattern. Within the unity of the local churches, "a real hierarchy of churches was recognized in response to the demands of the mission of the Church"[33] without, however, the fundamental equality of all churches being destroyed."

Let us now look at a little bit of history that has been mutually agreed by both sides:

Steps Towards A Reunited Church: A Sketch Of An Orthodox-Catholic Vision For The Future

my source:The Assembly of Canonical Orthodox Bishops USA

also published by the American Catholic Episcopal conference

also published by the American Catholic Episcopal conference

In the first paragraph of our excerpt, it shows that both sides agree on the early church seeing the whole catholic church made visible in the local eucharistic assembly

3. Divergent Histories. The historical roots of this difference in vision go back many centuries. Episcopal and regional structures of leadership have developed in different ways in the Churches of Christ, and are to some extent based on social and political expectations that reach back to early Christianity. In Christian antiquity, the primary reality of the local Church, centered in a city and bound by special concerns to the other Churches of the same province or region, served as the main model for Church unity. The bishop of a province’s metropolitan or capital city came to be recognized early as the one who presided at that province’s regular synods of bishops (see Apostolic Canon 34). Notwithstanding regional structural differences, a sense of shared faith and shared Apostolic origins, expressed in the shared Eucharist and in the mutual recognition of bishops, bound these local communities together in the consciousness of being one Church, while the community in each place saw itself as a full embodiment of the Church of the apostles.

In the Latin Church, a sense of the distinctive importance of the bishop of Rome, as the leading although not the sole spokesman for the apostolic tradition, goes back at least to the second century, and was expressed in a variety of ways. By the mid-fourth century, bishops of Rome began to intervene more explicitly in doctrinal and liturgical disputes in Italy and the Latin West, and through the seventh century took an increasingly influential, if geographically more distant, role in the Christological controversies that so sharply divided the Eastern Churches. It was only in the eleventh and twelfth centuries, during what is known as the Gregorian reforms, that the bishops of Rome, in response to centuries-old encroachments on the freedom and integrity of Church life by local secular rulers, began to assert the independence of a centrally-organized Catholic Church in a way that was to prove distinctive in Western society.

Gradually, a vision of the Church of Christ as a universal, socially independent single body -- parallel to the civil structure of the Empire, consisting of local or “particular” Churches, and held together by unity of faith and sacraments with the bishop of Rome -- developed in Latin Christianity, and became, for the West, the normative scheme for imagining the Church as a whole.

Even in the Middle Ages, however, this centralized vision of the universal Church was not shared by the Orthodox Churches. In April, 1136, for instance, a Roman legate – the German bishop Anselm of Havelberg -- visited Constantinople and engaged in a series of learned and irenic dialogues on issues dividing the Churches with the Byzantine Emperor’s representative, Archbishop Nicetas of Nicomedia. In the course of their conversations, Nicetas frequently expresses his love and respect for the Roman see, as having traditionally the “first place” among the three patriarchal sees – Rome, Alexandria and Antioch – that had been regarded, he says, since ancient times as “sisters.” Nicetas argues that the main scope of Rome’s authority among the other Churches was its right to receive appeals from other sees “in disputed cases,” in which “matters which were not covered by sure rules should be submitted to its judgment for decision” (Dialogues 3.7: PL 1217 D). Decisions of Western synods, however, which were then being held under papal sponsorship, were not, in Nicetas’s view, binding on the Eastern Churches. As Nicetas puts it, “Although we do not differ from the Roman Church in professing the same Catholic faith, still, because we do not attend councils with her in these times, how should we receive her decisions that have in fact been composed without our consent -- indeed, without our awareness?” (ibid. 1219 B). For the Orthodox consciousness, even in the twelfth century, the particular authority traditionally attached to the see of Rome has to be contextualized in regular synodal practice that includes representatives of all the Churches.

From this text we notice that both sides accept the ressourcement theologians premise that solutions to modern problems can be sought in Tradition, in this case in the first thousand years of the Church’s existence when East and West were one.

They also recognise that the way Tradition is shaped reflects the historical experience of particular churches, even though, to be recognised by the universal Church, the deeper coherence in Christ of these diverse forms must be discovered.

The Local Church

8. The one, holy, catholic and apostolic Church of which Christ is the head is present in the eucharistic synaxis of a local church under its bishop. He is the one who presides (the ‘proestos’). In the liturgical synaxis, the bishop makes visible the presence of Jesus Christ. In the local church (i.e. a diocese), the many faithful and clergy under the one bishop are united with one another in Christ, and are in communion with him in every aspect of the life of the Church, most especially in the celebration of the Eucharist. As St Ignatius of Antioch taught: ‘where the bishop is, there let all the people be, just as, where Jesus Christ is, we have the catholic church [katholike ekklesia]’.(4) Each local church celebrates in communion with all other local churches which confess the true faith and celebrate the same Eucharist. When a presbyter presides at the Eucharist, the local bishop is always commemorated as a sign of the unity of the local church. In the Eucharist, the proestos and the community are interdependent: the community cannot celebrate the Eucharist without a proestos, and the proestos, in turn, must celebrate with a community.

9. This interrelatedness between the proestos or bishop and the community is a constitutive element of the life of the local church. Together with the clergy, who are associated with his ministry, the local bishop acts in the midst of the faithful, who are Christ’s flock, as guarantor and servant of unity. As successor of the Apostles, he exercises his mission as one of service and love, shepherding his community, and leading it, as its head, to ever-deeper unity with Christ in the truth, maintaining the apostolic faith through the preaching of the Gospel and the celebration of the sacraments.

10. Since the bishop is the head of his local church, he represents his church to other local churches and in the communion of all the churches. Likewise, he makes that communion present to his own church. This is a fundamental principle of synodality.

It goes on to tell us of the importance of the regional churches. The:

The Church at the Universal Level

15. Between the fourth and the seventh centuries, the order (taxis) of the five patriarchal sees came to be recognised, based on and sanctioned by the ecumenical councils, with the see of Rome occupying the first place, exercising a primacy of honour (presbeia tes times), followed by the sees of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem, in that specific order, according to the canonical tradition.(11)

16. In the West, the primacy of the see of Rome was understood, particularly from the fourth century onwards, with reference to Peter’s role among the Apostles. The primacy of the bishop of Rome among the bishops was gradually interpreted as a prerogative that was his because he was successor of Peter, the first of the apostles.(12) This understanding was not adopted in the East, which had a different interpretation of the Scriptures and the Fathers on this point. Our dialogue may return to this matter in the future.

It is a principle of ressourcement theology that something that was allowed or differences that were tolerated over a considerable time within Catholic Tradition cannot be permanently disallowed or become intolerable by ecclesiastical decree. It was this principle that was cited by Pope Benedict XVI for allowing the celebration of the Tridentine Mass. He argued that ecclesiastical authority, even the authority of the pope, is a servant of Tradition and not its master. He said that he did not have the power to permanently forbid the Tridentine Mass, anymore than he had the power to permit female bishops and priests.

This principle, when applied to the dogmatic decrees on the papacy as well as to any other dogma that has been formulated in western Catholic tradition without a corresponding tradition in the Orthodox East, means that they are not teachings that we can ask the Orthodox to accept. The only thing necessary would be "the numerous Orthodox Churches and the Catholic Church would have to 'explicitly recognize each other as authentic embodiments of the one Church of Christ, founded on the apostles'” ( Joint statement of the North American Orthodox-Catholic Theological Consultation (2010).) As we have seen above, we have seen Rome recognising the Assyrian Church, "the Catholic Church recognises the Assyrian Church of the East as a true particular Church, built upon orthodox faith and apostolic succession." We have seen frequent references to Catholic and Orthodox churches as "sister churches" We must take such phrases seriously and move towards union with greater confidence; but we must also take the fears of the Patriarch of Moscow and "hasten very slowly" towards our goal.

That does not mean that all problems are solved. On the contrary, new problems emerge. What is the theological status of our “ecumenical” councils since the schism? Remember that authentic tradition arises from the synergy between the Holy Spirit and the Church operating in the liturgy, especially the Eucharist. Hence, once we recognise the authentic nature of Eastern and Oriental churches, we also recognise the authenticity of their traditions. An ecumenical council should reflect the underlying unity of all the traditions in the one, universal Tradition; and the opposite is also true: an ecumenical council, once accepted, should become a permanent part of each of the regional traditions.

In this context, whatever the legal status in Catholic canon law, the ecumenical councils of the West lack the quality of universality, as they do not represent all the traditions. However, they do represent the authentic western tradition and are products of the synergy between Church and the Spirit in the western Mass.

In this context, whatever the legal status in Catholic canon law, the ecumenical councils of the West lack the quality of universality, as they do not represent all the traditions. However, they do represent the authentic western tradition and are products of the synergy between Church and the Spirit in the western Mass.

My suggestion is that western ecumenical councils express the truth under the guidance of the Holy Spirit, but lack the balance and fullness that they would have had if no schism existed. They therefore cry out for the ecumenical treatment they are receiving.

If a comparison is made between current papal teaching of Pope John Paul II, Pope Benedict XVI and Pope Francis on the papal office and the ecumenical documents that have come out of the Orthodox-Catholic dialogue, you will be astonished at the influence of the latter on the former. Orthodox-Catholic dialogue is helping us to become more Catholic, not less Catholic. I hope that, one day, the Orthodox will see that Orthodox-Catholic dialogue will help the Orthodox to become more Orthodox, not less.

No comments:

Post a Comment