5 Things to know about Coptic Christians

A Coptic monk in the Monastery of Saint Bishoy, the most famous Coptic Orthodox monastery in Egypt. It is located in Wadi El Natrun (the Nitrian Desert), about 100km north and west of Cairo, Egypt. The monastery was founded by Saint Bishoy in the fourth century AD and is surrounded by a keep, which was built in the fifth century AD to protect the monastery against the attacks of the Berbers. (Thanks, Wikipedia)Who are these sisters and brothers suffering persecution for Christ?

From the Aleteia archives:

With the news of the terrible bombing during Divine Liturgy in a Coptic Orthodox church in Cairo, December 11, 2016, attention is being drawn again to the sufferings of Christian brothers and sisters in the Middle East. Who are these Coptic Christians? What do we share with them?

1. The Coptic Church is among the oldest Christian communities in the world.

Coptic Christians trace the founding of their church to a missionary journey by the evangelist St. Mark in the year 42. According to tradition, Mark spent his last days in Alexandria, then the capital of Greek-influenced Egypt and a center of knowledge and culture in the Mediterranean world. The first converts he made were the native Egyptians known as Copts for the language they spoke, which was the last surviving form of ancient Egyptian. (The word Copt is rooted in the ancient Egyptian word that describes a person from Egypt.)

2. Since the 5th century, the Coptic Orthodox Church has been out of communion with Rome and with the Eastern Orthodox churches. The Coptic Catholic Church, a tradition that split off at the same time, is today in full communion with Rome.

The divisions occurred over complex points of theology (particularly the understanding of the nature of Christ) and authority following the Council of Chalcedon in 451. The Coptic Orthodox Church is autocephalic (its own independent church). It has followers among Egyptian immigrants to other countries in Africa and around the world, including the US, and “daughter churches” in Ethiopia and Eritrea, and is in communion with the Oriental Orthodox churches. The Coptic language, which was written using Greek letters, remains the official liturgical language of the church, but over the centuries has been gradually replaced by Arabic, the vernacular of modern Egypt. Coptic Orthodox Christians, like many other Eastern and Oriental Orthodox Christians, follow the Julian calendar, with Christmas celebrated on January 7. Today, the Coptic Orthodox Church is headquartered in Cairo at St. Mark’s Cathedral (next door to the chapel where the bombing occurred), although the symbolic center of Coptic Christian life remains Alexandria.

The Coptic Catholic Church is headed by a Patriarch (bishop) who pledges obedience to Pope Francis. Coptic Catholics celebrate their own liturgical rite, and continue to use the Coptic language for Mass. The Coptic Catholic Church also traces its origins to St. Mark and Alexandria, but is today headquarted in Nasr City, a suburb of Cairo, at the cathedral of Our Lady of Egypt.

3. The Patriarch of the Coptic Orthodox is known as the Pope.

Before the divisions in Christianity between east and west, the patriarch (or head bishop) of the Coptic See of Alexandria was considered, by reason of the church’s age, primer inter pares (“first among equals”). By tradition, the first Patriarch of Alexandria was ordained by St. Mark himself. Like the Bishop of Rome, the Coptic Orthodox patriarch has been called pappas (“Father”) for generations, and today the Orthodox Patriarch carries the title of Pope. Pope Tawadros II succeeded to the office in 2012 after the death of Pope Shenouda III. Bishop Tawadros was selected by having his name chosen by a blind child from among ballots containing the names of three candidates. Pope Francis considers Pope Tawadros II his brother in Christ, and called him directly to offer sympathy and prayers after Sunday’s bombing.

4. Coptic Christians gave us the first school of catechesis and the blessing of the monastic tradition.

Under the Copts, Alexandria gave rise to a catechetical school where Christian doctrine took shape. Many of the early Church fathers lived or studied in Alexandria, joining the Greek philosophers and Jewish scholars who already made the city their home. Besides catechetical studies, the school taught humanities and mathematics. Its library contained carved wood texts with raised letters so the blind could study – long before the invention of Braille. The desert fathers of Egypt began the heremitic and monastic traditions that would later inspire St. Basil of Cappadocia in the East and St. Benedict in the West.

5. Coptic Christians have undergone persecution at various times throughout history.

After the Council of Chalcedon, Coptic Orthodox Christians suffered persecution at the hands of Byzantine Christians who considered them heretics. Many were tortured, imprisoned, and killed, but the Coptic Orthodox remained faithful to their understanding of Christology. With the rise of Islam and the Umayyad conquest of Egypt, most of the population retained their Coptic Christianity at first. Later the taxation and limitation of opportunities that were the price of being Christian under Islamic rule drew many Egyptians to convert to Islam. Gradually, Egypt became a Muslim-majority country, and today Coptic Christians represent only 10%-20% of the population. Since the rise of Islamic militarism, however, Copts (both Orthodox and Catholic), like other Middle Eastern Christians, have come under violent attack from terrorist groups.

xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

Relations between the Catholic Church and the Oriental Orthodox Churches

my source: CNEWA (Papal Agency)

The Oriental Orthodox Churches accept the first three ecumenical councils, but rejected the Christological definition of the fourth council, held in Chalcedon in 451. Today it is widely recognized by theologians and church leaders on both sides that the Christological differences between the Oriental Orthodox and those who accepted Chalcedon were only verbal, and that in fact both parties profess the same faith in Christ using different formulas. This new understanding was the result of official meetings between Popes and heads of Oriental Orthodox Churches, and unofficial meetings of theologians sponsored by the “Pro Oriente” Foundation in Vienna, Austria.

The work of the first Pro Oriente meeting in 1971 laid the groundwork for a historic Common Declaration signed by Pope Paul VI and Coptic Pope Shenouda III in 1973. Avoiding terminology that had been the source of disagreement in the past, the declaration made use of new language to express a common faith in Christ. Since that time Popes and Patriarchs have repeatedly asserted that their faith in Christ is the same. In their 1984 Common Declaration, Pope John Paul II and Syrian Patriarch Ignatius Zakka I Iwas stated that past schisms and divisions concerning the doctrine of the incarnation “in no way affect or touch the substance of their faith” because the disputes arose from differences in terminology and culture. As a result of all this, it can be safely said that the different Catholic and Oriental Orthodox Christological formulas are no longer a reason for division.

Progress has also been made in the area of ecclesiology. Both sides clearly recognize each other as churches, and the validity of each other’s sacraments. In their 1984 common declaration, Pope John Paul II and the Syrian Patriarch even authorized their faithful to receive the sacraments of penance, Eucharist and anointing of the sick in the other church when access to one of their own priests was morally or materially impossible. Until 2001, when a similar accord was reached with the Assyrian Church of the East, this was the only reciprocal agreement of this type.

In the midst of these contacts, a commission for dialogue between the Catholic Church and the Coptic Orthodox Church was set up in 1973, a dialogue with the Malankara Orthodox Syrian Church in October 1989, and another with the Malankara Syrian Orthodox Church in 1991. A national consultation between the Catholic Church and the Oriental Orthodox as a group in the United States has been meeting since 1978. This was the only example of such a dialogue anywhere in the world until 2003 when the Catholic Church and all the Oriental Orthodox churches agreed to establish a formal theological dialogue at the international level. So far it has met twelve times and has published two agreed statements: “Nature, Constitution and Mission of the Church” (2009) and “The Exercise of Communion in the Life of the Early Church and its Implications for our Search for Communion Today” (2015).

The Catholic-Oriental Orthodox relationship has already proved its importance by providing an example of how past disagreements over verbal formulas can be overcome. This was not done by one side capitulating to the other, but by moving beyond the words to the faith that those words are intended to express. Catholics and Oriental Orthodox now agree that, by means of different words and concepts, they express the same faith in Jesus Christ.

.APRIL 12, 2017 12:00AM EDT

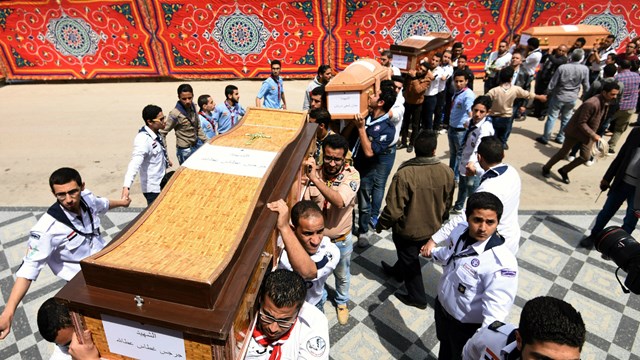

Egypt: Horrific Palm Sunday Bombings

State of Emergency Risks More Abuses

In Tanta, a city in the Nile Delta 95 kilometers north of Cairo, a man wearing concealed explosives managed to pass through a security check outside St. George’s Church and detonate himself near the front pews, killing at least 28 people and wounding 77, according to media reports. In Alexandria, church security camera footage showed another bomber trying to enter St. Mark’s Church through an open gate and being directed toward a metal detector guarded by police officers. When an officer stopped the man, he detonated his explosives, killing at least 17 people and wounding 48.

Pope Tawadros II, the leader of the Coptic Orthodox Church, was inside St. Mark’s Church but was not harmed, according to the Interior Ministry

Forgiveness: Muslims Moved as Coptic Christians Do the Unimaginable

Amid ISIS attacks, faithful response inspires Egyptian society.

JAYSON CASPER IN CAIRO| APRIL 20, 2017

Twelve seconds of silence is an awkward eternity on television. Amr Adeeb, perhaps the most prominent talk show host in Egypt, leaned forward as he searched for a response.

“The Copts of Egypt … are made of … steel!” he finally uttered.

Moments earlier, Adeeb was watching a colleague in a simple home in Alexandria speak with the widow of Naseem Faheem, the guard at St. Mark’s Cathedral in the seaside Mediterranean city.

On Palm Sunday, the guard had redirected a suicide bomber through the perimeter metal detector, where the terrorist detonated. Likely the first to die in the blast, Faheem saved the lives of dozens inside the church.

“I’m not angry at the one who did this,” said his wife, children by her side. “I’m telling him, ‘May God forgive you, and we also forgive you. Believe me, we forgive you.’....(see article)

Blood and Water Unite Catholics and Copts, Pope Francis Tells Egyptian Church

photo: abc news

The persecution of Christians and Baptism give divided Churches reason for solidarity

Coptic Christians are the spiritual children of those in the Church who separated in the fourth century, taking a different view of the nature of Christ. As such, they are classified as Oriental Orthodox, as opposed to Eastern Orthodox, and the relationship between Rome and Alexandria has been turbulent at times over the centuries.

But today, both blood and water give Copts and Catholics reason for solidarity: the water of Baptism and the blood of martyrdom.

On Tuesday, Pope Francis wrote to the leader of the Coptic Church, Pope Tawadros II, celebrating the fact that “after centuries of silence, misunderstanding and even hostility, Catholics and Copts increasingly are encountering one another, entering into dialogue, and cooperating together in proclaiming the Gospel and serving humanity.”

The letter was occasioned by the 43rd anniversary of the first encounter between Pope Paul VI and Coptic Orthodox Pope Shenouda III, an annual observance that has come to be known as the Day of Friendship between Copts and Catholics.

The relationship has certainly become more important in the past few years, as militant Islamism throughout the Middle East has threatened Christian communities. Even before the Islamic State group burst onto the international stage, Coptic churches throughout Egypt had been subject to attacks. But the dramatic images of ISIS militants leading 21 orange-clad Copts along a beach in Libya and then beheading them surely prompted Francis to write that he thinks and prays for the Christian communities in Egypt and the Middle East every day.

“So many [Middle East Christians] are experiencing great hardship and tragic situations,” the Pope wrote. “I am well aware of your grave concern for the situation in the Middle East, especially in Iraq and Syria, where our Christian brothers and sisters and other religious communities are facing daily trials. May God our Father grant peace and consolation to all those who suffer, and inspire the international community to respond wisely and justly to such unprecedented violence.”

Noting the ongoing efforts of an international dialogue between Catholics and Oriental Orthodox, Pope Francis said the two Churches are “able even now to make visible the communion uniting us.”

“Copts and Catholics can witness together to important values such as the holiness and dignity of every human life, the sanctity of marriage and family life, and respect for the creation entrusted to us by God,” Francis wrote. “In the face of many contemporary challenges, Copts and Catholics are called to offer a common response founded upon the Gospel. As we continue our earthly pilgrimage, if we learn to bear each other’s burdens and to exchange the rich patrimony of our respective traditions, then we will see more clearly that what unites us is greater than what divides us.

“In this renewed spirit of friendship, the Lord helps us to see that the bond uniting us is born of the same call and mission we received from the Father on the day of our baptism,” the Pontiff continued. “Indeed, it is through baptism that we become members of the one Body of Christ that is the Church.”

Francis and Tawadros met for the first time three years ago, marking the 40th anniversary of the meeting of their predecessors.

Popes Francis, Tawadros II sign declaration to end controversy over rebaptism

The deceleration seeks “not to repeat baptism” when converting from one church to the other

FARAH BAHGAT | 29 APRIL 2017

source: Daily News

my source: Pravmir.com

Pope Francis of the Roman Catholic Church and Pope Tawadros II of the Coptic Orthodox Church signed a declaration on Friday during the former’s visit to Egypt, agreeing that rebaptism should not be held for Christians wishing to convert from one church to the other.

The declaration, published by the Vatican, stated, “today we, Pope Francis and Pope Tawadros II, in order to please the heart of Lord Jesus, as well as that of our sons and daughters in faith, mutually declare that we, with one mind and heart, will seek sincerely not to repeat the baptism that has been administered in either of our Churches for any person who wishes to join the other. This we confess in obedience to the Holy Scriptures and the faith of the three Ecumenical Councils assembled in Nicaea, Constantinople, and Ephesus.”

Ishak Ibrahim, researcher at the Egyptian Initiative for Personal Rights (EIPR), explained that rebaptism had been one of the main doctrinal differences throughout the past 15 centuries, in which churches did not acknowledge one another.

“Baptism is considered one of the seven sacred sacraments of Christianity; it symbolises how a person is reborn when joining Christianity,” Ibrahim clarified, adding that Christians went through baptism only once in their life during their early childhood, hence, when churches did not acknowledge the baptism of one another, a person had to go through rebaptism if they wanted to transfer from the Catholic Church to the Orthodox or vice versa.

“The declaration’s importance lies in its symbolism and the message within, which shows that churches are able to coexist,” he added. “I believe that the majority of Christians will not oppose the declaration. Of course there will be opposition, but I don’t think it will result in any severe consequences.”

Researcher Marianne Sedhom from the Egyptian Center for Public Policy Studies described the consequences of the declaration as “merely theological,” explaining that it would have minimal impact on citizens but rather unified churches.

Friday’s agreement will end the previous standards that were practiced under late Pope Shenouda III, who asserted that one had to undergo rebaptism if one was not baptised in an Orthodox Church, according to state-owned newspaper Al Ahram.