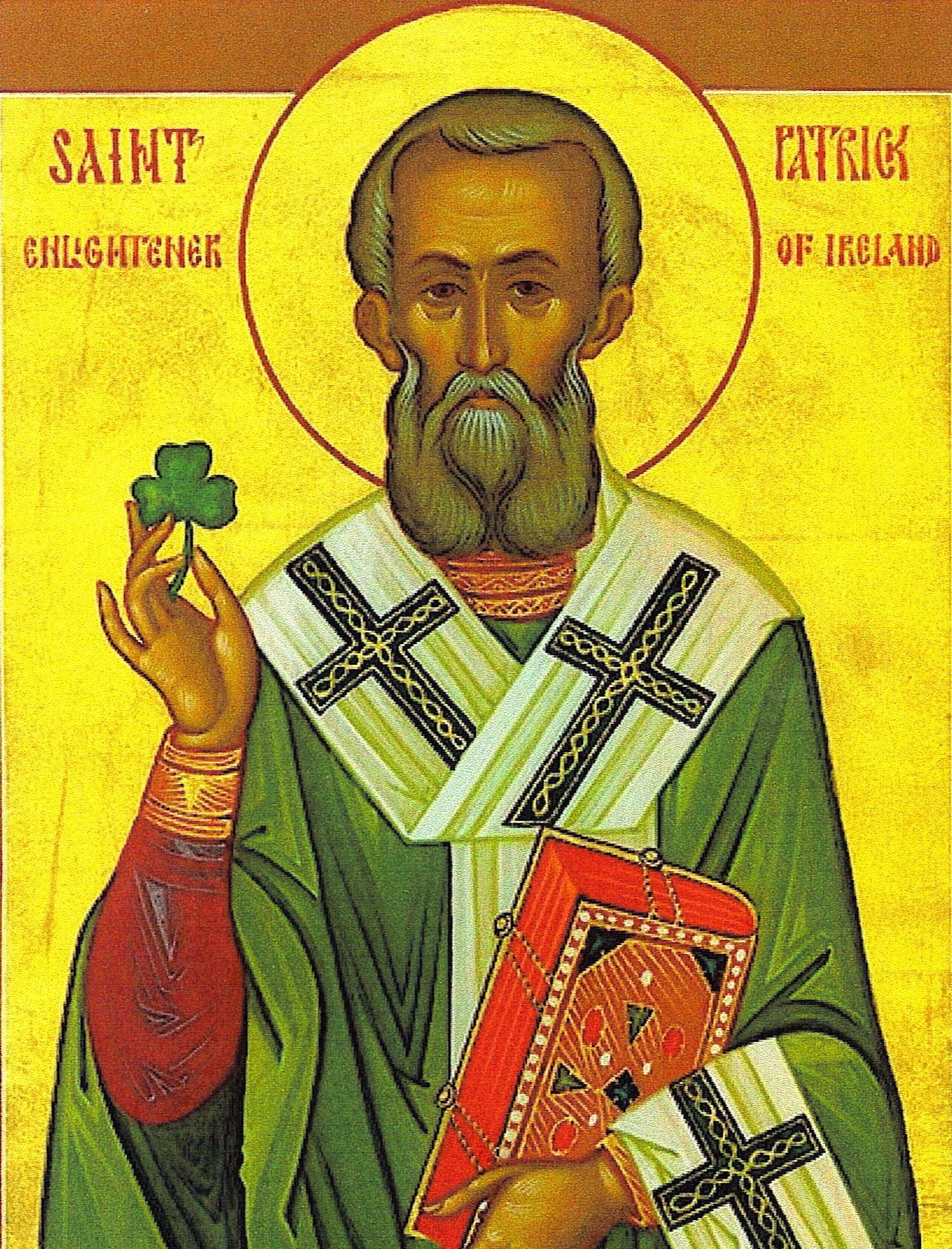

Saint Patrick was a fifth-century Romano-British Christian missionary and bishop in Ireland. Known as the "Apostle of Ireland", he is the primary patron saint of Ireland, along with saints Brigit of Kildare and Columba.

A special reason to be festive this year, is the recent recognition of St. Patrick by the Holy Synod of the Russian Orthodox Church. The day honouring CKfollows the Julian calendar, which is 13 days after the Gregorian calendar, placing Russian St. Patrick’s day on March 30.

Father Igor Fomin, rector of the church of the Holy Prince Alexander Nevsky at MGIMO says that “holy justice has been served,” when it comes to St. Patrick, since his work took place before the east and west split of the Church.

“Having always loved him, we can now pray for him officially,” he said, adding that the saints labour was not always duly noticed.

However, the celebration of St. Patrick falls in the middle of Russian Orthodox lent and does not allow for the traditional beer-guzzling, associated with the holiday. Father Igor says that drinking in excess to honor a saint is much like showing up heavily intoxicated at your mother’s gravesite, it happens, but it has nothing to do with the holiday or honouring the deceased.

“I am very happy that our St. Patrick’s day falls on a different date, that way the traditions associated with it, that are strictly cultural and not religious can be ignored.

Yet, Russians enjoy honouring the saint, like many others do around the world, with a pint and a dance. “You can go to bars, you can drink quality draft beer, sometimes, and dance on tables and it’s a day when no one frowns upon that, in fact, it’s welcomed,” says Roman Kanunnikov, digital advertising manager and Irish folk dancer. (pravmir.com)

St. Patrick, we have said, introduced the monastic system into Ireland. It is said the Irish rule was most rigorous. It was more or less a copy of the French rule, as the French was a copy of the Thebaid. When compared with the rule of St. Basil or St. Benedict no doubt the Irish rule was much stricter, and when the monks of a certain monastery got the option of following either the Columban or the Benedictine rule all gave their preference to the Benedictine. If the Columban monks had a written rule no trace of it has been discovered. The principal practices of their monasteries are, of course, known from many sources. With regard to food the rule was very strict. Only one meal a day, at 3 o'clock p.m., was allowed, except on Sundays and Feast days. Wednesdays and Fridays were fast days, except the interval between Easter and Whit Sunday. Lent and Advent were fast seasons. The food allowed for days not fast was barley bread, milk, fish, and eggs. Flesh meat was not allowed except on great feasts. Milk, butter, and flesh were prohibited on fast days. The daily routine of monastic life was prayer, study, and manual labour.

Irish monasteries grew up quickly to be most important institutions both for Church and State. They were the soul of the Irish Church. The abbots of the principal monasteries—as Clonard, Armagh, Clonmacnoise, Swords, etc.—were of the highest rank and held in the greatest esteem. They wielded great power and had vast influence. The abbot usually was only a presbyter, but in the large monasteries there were one or more resident bishops who conferred orders and discharged the other functions of a bishop. The abbot was superior of the house, and all were subject to him.

Some in their ignorance are apt to look with contempt on old institutions, especially on the old Irish monasteries. The truth is these latter were great in every way. " Every tree is known by its fruit." If we judge them on that score they were institutions of the highest excellence. Let us first glance at the curicula of the schools. The following were among the subjects taught: Latin, Greek, Hebrew, grammar, rhetoric, poetry, arithmetic, chronology, the Holy Places, hymns, sermons, natural science, history and interpretation of Sacred Scripture. The latter subject was specialised and treated profoundly.

Happily there are extant works produced by members of those institutions. These afford ample proof of a high order of scholarship and culture. We have the works of St. Columbanus, which consist of his Monastic Rule in ten chapters; a book on daily penance of the monks; seventeen short sermons; a book on the measure of penances; an instruction concerning the eight principal vices; a considerable number of Latin verses; and five Epistles—two addressed to Boniface IV., one to Gregory the Great, one to the members of a Gallican Synod on the question of Easter, and one to the monks of his monastery of Luxeuil. Born 432, died 500.

Aileran, who died in 664, professor of Clonard, wrote, according to Colgan, the Fourth Life of St. Patrick and the Lives of St. Brigid and St. Fechin. He also wrote a book on the mystical interpretation of the Ancestry of Our Lord Jesus Christ. This is published in the Benedictine edition of the Fathers, and the editors say they publish it though Aileran was not a Benedictine., because he " unfoulded the meaning of the Sacred Scripture with so much learning and ingenuity that every student of the Sacred Volume and especially preachers of the Divine Word will regard the publication as most acceptable." This is high praise from competent and independent judges.

Sedulius, who lived in the eighth century, was, according to Ware and Usher, one of the most learned men of the age. He wrote theological treatises and criticisms. Cogitosus wrote the Life of St. Brigid in the sixth century. In the seventh century Ireland, being free from the convulsions of the surrounding nations, became the school of learning to the rest of Europe. Commenius, Abbot of Iona in 657, has left a very learned and argumentative tract. He cites Jerome, Origin, Cyril, Cyprian, Gregory, Augustine, etc. He adduces Cyril's cycles of 95 years; Victorius's of 532 years, with those of Augustine, Morinus, and Pachomius. He quotes the canons of the Church, which shows his acquaintance with ecclesiastical discipline. The Easter question was the subject on which he wrote.

Virgilius flourished in the 8th century, who was deeply versed in mathematics, geography, and astronomy. He was the first to teach the sphericity of the earth, and the antipodes.

A few quotations from foreigners on Irish schools will not be out of place. Alcuin, the most celebrated scholar of the age, writing of Willibrord, a Northumbrian, Archbishop of Utrecht, says: " When he arrived at the 20th year of his age, he was inflamed with the desire of a stricter life and a love of visiting foreign parts. And because he heard that learning flourished greatly in Ireland he intended to go there, moved principally thereto by the fame of its holy men, particularly of the blessed father Egbert and the venerable priest Wigbert, who both for the love of a celestial country had forsaken their houses and kindred, and retired to Ireland. The blessed Willibrord, emulating the sanctity of these two holy men, embarked for this island, where he joined himself to their society, like a diligent bee, that he might, by means of their vicinity, suck the melifluous flowers of piety and build up in the hive of his own breast sweet honeycombs of virtue. There for the space of twelve years under those illustrious masters he treasured up knowledge and virtue, that he might be enabled to become the teacher of many nations."

The Venerable Bede writes: " It was now that many noble English and others of inferior rank, leaving their native country, withdrew to Ireland, to cultivate letters or lead a life of greater purity. Some became monks, others attended the lectures of celebrated teachers; these the Irish most cheerfully received and supplied without any recompense, with food, books, and instruction."

Mosheim writes: " That the Hibernians were lovers of learning, and distinguished themselves in those times of ignorance by the culture of the sciences beyond all other European nations, travelling the most distant lands, with a view to improve and communicate their knowledge, is a fact with which I have long been acquainted, as we see them in the most authentic records of antiquity discharging with the highest reputation and applause the functions of doctors in France, Germany, and Italy both during this and the following century. But that these Hibernians were the first teachers of scholastic theology in Europe, and so early as the 8th century illustrated the doctrines of religion by the principles of philosophy I learned but lately from the testimony of Benedict, Abbot of Amuane in the province of Languedoc, who lived in this period, and some of whose productions are published by Baluzius in the fifth tome of his Miscellanea."

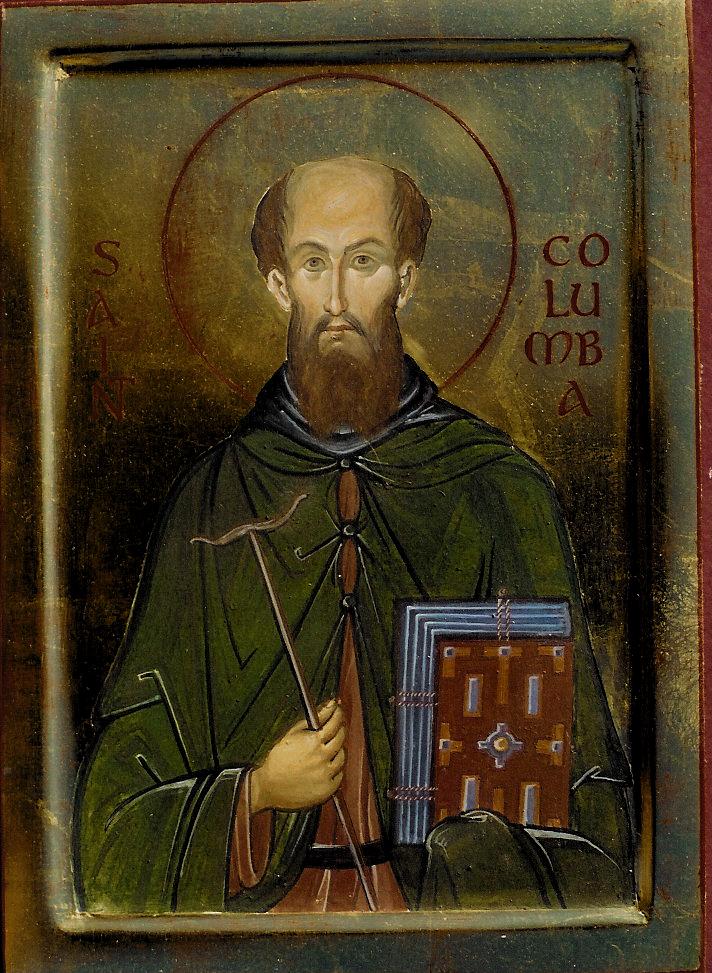

The Irish, according to this learned writer, not only distinguished themselves by the culture of the sciences beyond all other European nations, but travelled the most distant lands with a view to improve and communicate their knowledge. Not only did they convert and civilise many countries of Europe, they also imparted a knowledge of agriculture, built asylums, hospitals, refuges, and introduced the arts and sciences. Saints Colman, Modestus, Virgilius, and others laboured in Austria. Saints Kilian and Firmin were the apostles of Franconia. Columbanus, Gall, Fridolin, were the first to preach the Gospel in Burgundy, Alsace, Helvetia, Suevia. St. Virgilius was the apostle of all Bavaria. St. Columba preached to the Picts, and in the north of England. The labours of the Irish monks extended to many other regions, including Switzerland, Saxony, and Northern Germany. Those people were not lazy.

Irish worker discovers ancient manuscript that links Irish church to Egypt

Philip Kosloski

| Nov 30, 2016

Brian Washburn

The conservator called the finding miraculous: “We never before had to deal with a manuscript recovered from a bog."

In 2006 an Irish worker discovered an amazing find while digging in a bog with his backhoe at Fadden More.

Sticking out of the earth was an ancient manuscript, miraculously intact after more than a thousand years. Archeologists were quickly notified and carefully retrieved the manuscript and began at once investigating it and putting the pieces together.

"The reason for my particular interest in the icons of St Anthony was that during the Dark Ages the saint was also a favourite subject for the Pictish artists of my native Scotland, as well as for those across the sea in Ireland. The Celtic monks of both countries consciously looked on St Anthony as their ideal and their prototype, and the proudest boast of Celtic monasticism was that, in the words of the seventh-century Antiphonary of the Irish monastery of Bangor:

This house full of delight

Is built on the rock

And indeed the true vine

Transplanted out of Egypt.

Moreover, the Egyptian ancestry of the Celtic Church was acknowledged by contemporaries: in a letter to Charlemagne, the English scholar-monk Alcuin described the Celtic Culdees as ‘pueri egyptiaci’, the children of the Egyptians. Whether this implied direct contact between Coptic Egypt and Celtic Ireland and Scotland is a matter of scholarly debate. Common sense suggests that it is unlikely, yet a growing body of scholars think that that is exactly what Alcuin may have meant.

There are an extraordinary number of otherwise inexplicable similarities between the Celtic and Coptic Churches which were shared by no other Western Churches. In both, the bishops wore crowns rather than mitres and held T-shaped Tau crosses rather than crooks or crosiers (compare icons below).

Saint Antony (Egypt)

St Columba

Scotland

In both, the hand-bell played a very prominent place in ritual, so much so that in early Irish sculpture clerics are distinguished form lay persons by placing a clochette in their hand. The same device performs a similar function on Coptic stele – yet bells of any sort are quite unknown in the dominant Greek or Latin Churches until the tenth century at the earliest.

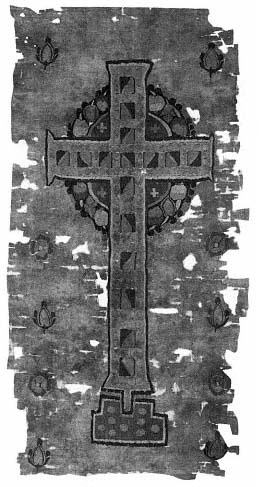

Stranger still, the Celtic wheel cross, the most common symbol of Celtic Christianity, has recently been shown to have been a Coptic invention, depicted on a Coptic burial pall (see image below) of the fifth century, three centuries before the design first appears in Scotland and Ireland.

Coptic burial pall, fifth to seventh century. 138.4 by 68.9 cm.

Photograph courtesy The Minneapolis Institute of Arts.

Certainly there is a growing body of evidence to suggest that contact between the Mediterranean and the Celtic fringe was possible. Egyptian pottery – perhaps originally containing wine or olive oil – has been found during excavations at Tintagel Castle in Cornwall, the mythical birthplace of King Arthur. The Irish Litany of Saints remembers ‘the seven monks of Egypt (who lived) in Disert Uilaig” on the west coast of Ireland. But the fullest account of direct contact is given by none other than Sophronius himself. In his “Life of John the Almsgiver” (the saintly Patriarch with whom he and Moschos fled Alexandria in 614 A.D.), Sophronius tells the story of an accidental voyage to Britain – more specifically, in all likelihood, to Cornwall – undertaken by a bankrupt young Alexandrian aristocrat to whom the Patriarch has lent money:

“We sailed for twenty days and nights (reported the man on his return) and owing to a violent wind we were unable to tell in what direction we were going either by the stars or by the coast. But the only thing we knew was that the steersman saw (an apparition of) the Patriarch (John the Almsgiver) by his side, holding his tiller and saying to him: ‘Fear not! You are sailing quite right.’ Then, after the twentieth day, we caught sight of the islands of Britain, and when we had landed we found a famine raging there. Accordingly, when we told the chief man of the town that we were laden with corn, he said, ‘God has brought you at the right moment. Choose as you wish either one “nomisma” for each bushel or a return freight of tin.’ And we chose half of each. Then we set sail again and joyfully made once more for Alexandria, putting in on our way at Pentapolis (in modern Libya)." (Orthodox Link)

The Monastic Vocation

"The purpose of the monastery is to find your heart, your true self; so, in a real sense, your heart is praying all the time, and you don't even know it; because God is creating you all the time, at every moment of the day; and, at that place where your life and God's life meet, that is where you want to live."

Thus speaks a monk in the excellent video "New Melleray: One Thing". It is so good that I included it, even if it is in America and not Ireland.

If Orthodox readers can put their prejudices aside for a moment and judge anything that is different from their own Tradition is automatically inferior, if they go behind the differences, they will discover the same monastic tradition, even if the style is quite different. While an Orthodox church is full of icons that reflect the fact that the Eucharistic community is where heaven and earth meet, a Cistercian church reflects in its austerity the Egyptian desert or the bleak landscape of Skellig Michael.

The lecture by Bernard McGinn is very good on Irish monasticism, and the nuns discussing their various vocations in "School of Love" is an excellent source for those who wish to understand monastic life.

Some of you may find an Egyptian-Irish connection in the early centuries a bit unbelievable. Actually, there was perhaps probably more contact at times between Egypt and western Christianity than between western Christianity, at least at a distance from the Mediterranean, and Byzantium. Alexandria exported wheat all over the empire, and this formed the basis of its almost universal connections.

No comments:

Post a Comment