The Feast of Christmas is a glimpse at the mystery of a creation transfigured by its close relationship with God only made possible by the Incarnation. The Church looks at the birth of Jesus through the eyes of faith, seeing in this singular event that "God was man in Palestine, and lives today in Bread and Wine."

This transformation of creation began in the womb of the Blessed Virgin with Jesus' conception, appeared among us in his birth, revealed and taught during his public ministry, and reached maturity through his death, "It is consummated!", and reached perfection in the resurrection of Jesus.

This transformation of creation began in the womb of the Blessed Virgin with Jesus' conception, appeared among us in his birth, revealed and taught during his public ministry, and reached maturity through his death, "It is consummated!", and reached perfection in the resurrection of Jesus. His resurrection is the full effect on created nature of sharing in the divine life that has been made possible by the incarnation; and, because sin has radically distorted humanity, we can only share in the effects of the Incarnation by dying and rising with Christ.

Hence, as the word "Christmas" implies, at its very centre is the "Mass" in which, by participation in the very body and blood of Christ, the same body that was born in Bethlehem, we proclaim Christ's death until he shall return and heaven and earth will be transformed totally by his resurrection.

Meanwhile, for those with faith, the world is already transformed by his presence, not only the Scriptures that, from being historical documents, become for us Word of God, and the sacraments that are transformed from being merely religious ceremonies to being acts of Christ in his Church, but in every person we meet, every circumstance we find ourselves in, every moment of our day, we discover, is full of Christ's presence, beckoning us, inspiring us, teaching us, challenging us and, above all loving us and requiring our response. As we obey the Lord's commandment, "Love one another as I love you;" as we manifest Christ's love for those in need by doing for them what love demands, as we reflect for others the relationship we have with Christ in prayer, as we do his will rather than our own, so we make visible to the world the Kingdom of God. Only love makes the Kingdom visible, "That you may be one...that the world may know that You have sent me." On the Last Day, all this will be visible and obvious to all, and every day will be like Christmas; and we will be accompanied by the angels and the saints, and we will join them in singing the praise of the Lord whom we will see with our own eyes as the shepherds and the wise men did.

On the Last Day, we will realise that the Christian legend is nearer the truth of it than any description without faith could ever be, however accurate they may describe what they see.

The Pope's homily from Midnight Mass in St Peter's Basilica 2015.

Tonight “a great light” shines forth (Is 9:1); the light of Jesus’ birth shines all about us. How true and timely are the words of the prophet Isaiah which we have just heard: “You have brought abundant joy and great rejoicing” (9:2)! Our heart was already joyful in awaiting this moment; now that joy abounds and overflows, for the promise has been at last fulfilled. Joy and gladness are a sure sign that the message contained in the mystery of this night is truly from God. There is no room for doubt; let us leave that to the skeptics who, by looking to reason alone, never find the truth. There is no room for the indifference which reigns in the hearts of those unable to love for fear of losing something. All sadness has been banished, for the Child Jesus brings true comfort to every heart.

Today, the Son of God is born, and everything changes. The Saviour of the world comes to partake of our human nature; no longer are we alone and forsaken. The Virgin offers us her Son as the beginning of a new life. The true light has come to illumine our lives so often beset by the darkness of sin. Today we once more discover who we are! Tonight we have been shown the way to reach the journey’s end. Now must we put away all fear and dread, for the light shows us the path to Bethlehem. We must not be laggards; we are not permitted to stand idle. We must set out to see our Saviour lying in a manger. This is the reason for our joy and gladness: this Child has been “born to us”; he was “given to us”, as Isaiah proclaims (cf. 9:5). The people who for for two thousand years has traversed all the pathways of the world in order to allow every man and woman to share in this joy is now given the mission of making known “the Prince of peace” and becoming his effective servant in the midst of the nations.

ch-advert-12-600

So when we hear tell of the birth of Christ, let us be silent and let the Child speak. Let us take his words to heart in rapt contemplation of his face. If we take him in our arms and let ourselves be embraced by him, he will bring us unending peace of heart. This Child teaches us what is truly essential in our lives. He was born into the poverty of this world; there was no room in the inn for him and his family. He found shelter and support in a stable and was laid in a manger for animals. And yet, from this nothingness, the light of God’s glory shines forth. From now on, the way of authentic liberation and perennial redemption is open to every man and woman who is simple of heart. This Child, whose face radiates the goodness, mercy and love of God the Father, trains us, his disciples, as Saint Paul says, “to reject godless ways” and the richness of the world, in order to live “temperately, justly and devoutly” (Tit 2:12).

In a society so often intoxicated by consumerism and hedonism, wealth and extravagance, appearances and narcissism, this Child calls us to act soberly, in other words, in a way that is simple, balanced, consistent, capable of seeing and doing what is essential. In a world which all too often is merciless to the sinner and lenient to the sin, we need to cultivate a strong sense of justice, to discern and to do God’s will. Amid a culture of indifference which not infrequently turns ruthless, our style of life should instead be devout, filled with empathy, compassion and mercy, drawn daily from the wellspring of prayer.

Like the shepherds of Bethlehem, may we too, with eyes full of amazement and wonder, gaze upon the Child Jesus, the Son of God. And in his presence may our hearts burst forth in prayer: “Show us, Lord, your mercy, and grant us your salvation” (Ps 85:8)

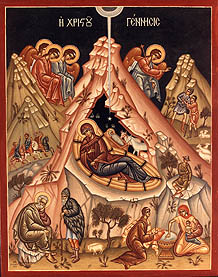

The Mystery of Christmas

Dom Prosper Gueranger O.S.B.

Everything is mystery in this holy season. The Word of God, whose generation is before the day-star, is born in time: A Child is God. A Virgin becomes a Mother and remains a Virgin. Things divine are commingled with those that are human. And the sublime, the ineffable antithesis, expressed by the Beloved Disciple in those words of his Gospel, The Word was made flesh, is repeated in a thousand different ways in all the prayers of the Church.

And rightly so, for it admirably embodies the whole of the great portent that unites in one Person the nature of Man and the nature of God.

The splendor of this mystery dazzles the understanding, but it inundates the heart with joy. It is the consummation of the designs of God in time. It is the endless subject of admiration and wonder to the Angels and Saints. Nay, it is the source and cause of their beatitude. Let us see how the Church offers this mystery to her children, veiled under the symbolism of the Liturgy.

Why the 25th of December?

The four weeks of our preparation are over. They were the image of the 4,000 years that preceded the great coming, and we have reached the 25th day of the month of December as a long desired place of sweetest rest. But, why is it that the celebration of our Savior's Birth should be the perpetual privilege of this one fixed day, while the whole liturgical cycle has to be changed and remodeled every year in order to yield to that ever-varying day which is to be the feast of His Resurrection, Easter Sunday?

|

| Adoring Christ on December 25 |

The question is a very natural one, and we find it proposed and answered as far back as the fourth century by St. Augustine in his celebrated Epistle to Januarius. The holy Doctor offers this explanation: We solemnize the day of our Savior's Birth so that we may honor that Birth, which was for our salvation. But, the precise day of the week on which He was born is void of any mystical signification. … We should not suppose, however, that because the Feast of Jesus' Birth is not fixed to any particular day of the week, there is no mystery expressed by its always being on the 25th of December.

First, we may observe, with the old liturgists, that the Feast of Christmas is kept by turns on each of the days of the week, that thus its holiness may cleanse and rid them of the curse that Adam's sin had put upon them.

Second, the great mystery of the 25th of December being the Feast of our Savior's Birth refers not to the division of time marked out by God himself, but to the course of that great luminary that gives life to the world, because it gives light and warmth. Jesus, our Savior, the Light of the World, was born when the night of idolatry and crime was at its darkest. The day of His Birth, the 25th of December, is the time when the material sun begins to gain its ascendancy over the reign of gloomy night and show to the world its triumph of brightness.

In our Advent, we showed, following the Holy Fathers, that the diminution of physical light may be considered as emblematic of those dismal times which preceded the Incarnation. We joined our prayers with those of the people of the Old Testament, and with our Holy Mother the Church we cried out to the Divine Orient, the Sun of Justice, that He would deign to come and deliver us from the twofold death of body and soul.

God has heard our prayers, and it is on the day of the Winter Solstice - which the pagans of old made so much of by their fears and rejoicings - that He gives us both the increase of the natural light and the One Who is the Light of our souls.

St. Gregory of Nyssa, St. Ambrose, St. Maximus of Turin, St. Leo, St. Bernard and the principal liturgists, dwell with complacency on this profound mystery, which the Creator of the universe has willed should mark both the natural and the supernatural world. We shall find the Church also making continual allusion to it during this season of Christmas, as she did in that of Advent.

‘Darkness decreases, light increases’

“On this the Day which the Lord hath made,” says St. Gregory of Nyssa, “darkness decreases, light increases, and night is driven back again. No, brethren, it is not by chance, nor by any created will, that this natural change begins on the day when He shows himself in the brightness of His coming, which is the spiritual life of the world. It is nature revealing, under this symbol, a secret to those whose eye is quick enough to see it, that is, to those who are able to appreciate this circumstance of our Savior's coming.

|

| A light appears in the darkness of winter |

“Nature seems to me to say: ‘Know, O man! that under the things that I show thee, mysteries lie concealed. Hast thou not seen the night that had grown so long suddenly checked? Learn hence, that the black night of sin, which had reached its height by the accumulation of every guilty device, is this day stopped in its course. Yes, from this day forward its duration shall be shortened, until at length there shall be naught but light. Look, I pray thee, on the sun; and see how his rays are stronger, and his position higher in the heavens: Learn from that how the other light, the light of the Gospel, is now shedding itself over the whole earth.”

“Let us rejoice, my Brethren,” cries out St. Augustine. “This day is sacred not because of the visible sun, but because of the Birth of He who is the invisible Creator of the sun... He chose this day whereon to be born, as He chose the Mother of whom to be born, and He bade both the day and the Mother. The day He chose was that on which the light begins to increase, and it typifies the work of Christ, Who renews our interior man day by day. For the eternal Creator, having willed to be born in time, His Birthday would necessarily be in harmony with the rest of his creation.”

The same St. Augustine, in another sermon for the same Feast, gives us the interpretation of a mysterious expression of St. John the Baptist, which admirably confirms the tradition of the Church. The great Precursor said on one occasion, when speaking of Christ: “He must increase, but I must decrease.”

| ||

|

These prophetic words signify, in their literal sense that the Baptist's mission was at its close because Jesus was entering upon His. But they convey, as St. Augustine assures us, a second meaning: “John came into this world at the season of the year when the length of the day decreases; Jesus was born in the season when the length of the day increases. Thus there is mystery both in the rising of that glorious star, the Baptist, at the summer solstice, and in the rising of our Divine Sun in the dark season of winter.”

There have been men who dared to scoff at Christianity as superstition because they discovered that the ancient pagans used to keep a feast of the sun on the winter solstice. In their shallow erudition they concluded that a Religion could not be divinely instituted that had certain rites or customs originating in an analogy to certain phenomena of this world.

In other words, these writers denied what Revelation asserts, namely, that God only created this world for the sake of His Christ and His Church. The very facts which these enemies to the true Faith are, to us Catholics, additional proof of its being worthy of our most devoted love.

Thus, then, have we explained the fundamental mystery of these Forty Days of Christmas by having shown the grand secret hidden in the choice made by God's eternal decree, that the 25th day of December should be the Birthday of God upon this earth.

Pope Francis at the Christmas Vigil Mass, Christmas Eve

At 9:30 on December 24, the Holy Father Francis presided in the Vatican Basilica at the “Christmas Midnight Mass” for the Solemnity of the Nativity of the Lord 2016. During the Mass, after the proclamation of the Holy Gospel, the Pope gave the following homily.

The essence of the homily is in these words: "Christmas has essentially a flavour of hope because, notwithstanding the darker aspects of our lives, God’s light shines out. His gentle light does not make us fear; God who is in love with us, draws us to himself with his tenderness, born poor and fragile among us, as one of us."

Here is the complete homily:

“The grace of God has appeared for the salvation of all men” (Tit 2:11). The words of the Apostle Paul reveal the mystery of this holy night: the grace of God has appeared, his gift is free; in the Child given unto us the love of God is made visible.

It is a night of glory, that glory proclaimed by the angels in Bethlehem and also by us today all over the world. It is a night of joy, because from this day forth, and for all times, the infinite and eternal God is God with us: he is not far off, we need not search for him in the heavens or in mystical notions; he is close, he is been made man and will never distance himself from our humanity, which he has made his own.

It is a night of light: that light, prophesied by Isaiah (cf. 9:1), which would illumine those who walk in darkness, has appeared and enveloped the shepherds of Bethlehem (cf. Lk 2:9).

The shepherds simply discover that “unto us a child is born” (Is 9:5) and they understand that all this glory, all this joy, all this light converges to one single point, that sign which the angel indicated to them: “you will find a baby wrapped in swaddling clothes and lying in a manger” (Lk 2:12).

This is the enduring sign to find Jesus.

Not just then, but also today.

If we want to celebrate Christmas authentically, we need to contemplate this sign: the fragile simplicity of a small newborn, the meekness of where he lies, the tender affection of the swaddling clothes. God is there.

With this sign the Gospel reveals a paradox: it speaks of the emperor, the governor, the mighty of those times, but God does not make himself present there; he does not appear in the grand hall of a royal palace, but in the poverty of a stable; not in pomp and show, but in the simplicity of life; not in power, but in a smallness which surprises.

In order to discover him, we need to go there, where he is: we need to bow down, humble ourselves, make ourselves small.

The Child who is born challenges us: he calls us to leave behind fleeting illusions and go to the essence, to renounce our insatiable claims, to abandon our endless dissatisfaction and sadness for something we will never have. It will help us to leave these things behind in order to rediscover in the simplicity of the God-child, peace, joy and the meaning of life.

Let us allow the Child in the manger to challenge us, but let us also allow ourselves to be challenged by the children of today’s world, who are not lying in a cot caressed with the affection of a mother and father, but rather suffer the squalid “mangers that devour dignity”: hiding underground to escape bombardment, on the pavements of a large city, at the bottom of a boat overladen with immigrants.

Let us allow ourselves to be challenged by the children who are not allowed to be born, by those who cry because no one satiates their hunger, by those who do have not toys in their hands, but rather weapons.

The mystery of Christmas, which is light and joy, questions and unsettles us, because it is at once both a mystery of hope and of sadness.

It bears within itself the taste of sadness, inasmuch as love is not received, and life discarded.

This happened to Joseph and Mary, who found the doors closed, and placed Jesus in a manger, “because there was no place for them in the inn” (v. 7).

Jesus was born rejected by some and regarded by many others with indifference.

Today also the same indifference can exist, when Christmas becomes a feast where the protagonists are ourselves, rather than Jesus; when the lights of commerce cast the light of God into the shadows; when we are concerned for gifts but cold towards those who are marginalized.

Yet Christmas has essentially a flavour of hope because, notwithstanding the darker aspects of our lives, God’s light shines out.

His gentle light does not make us fear; God who is in love with us, draws us to himself with his tenderness, born poor and fragile among us, as one of us.

He is born in Bethlehem, which means “house of bread.”

In this way he seems to tell us that he is born as bread for us; he enters life to give us his life; he comes into our world to give us his love.

He does not come to devour or to command but to nourish and to serve.

Thus there is a direct thread joining the manger and the cross, where Jesus will become bread that is broken: it is the direct thread of love which is given and which saves us, which brings light to our lives, and peace to our hearts.

The shepherds grasped this in that night. They were among the marginalized of those times. But no one is marginalized in the sight of God and it was precisely they who were invited to the Nativity.

Those who felt sure of themselves, self-sufficient, were at home with their possessions; the shepherds instead “went with haste” (cf. Lk 2:16).

Let us allow ourselves also to be challenged and convened tonight by Jesus.

Let us go to him with trust, from that area in us we feel to be marginalized, from our own limitations.

Let us touch the tenderness which saves.

Let us draw close to God who draws close to us, let us pause to look upon the crib, and imagine the birth of Jesus: light, peace, utmost poverty, and rejection.

Let us enter into the real Nativity with the shepherds, taking to Jesus all that we are, our alienation, our unhealed wounds.

Then, in Jesus we will enjoy the flavour of the true spirit of Christmas: the beauty of being loved by God.

With Mary and Joseph we pause before the manger, before Jesus who is born as bread for my life.

Contemplating his humble and infinite love, let us say to him: thank you, thank you because you have done all this for me.

Pope Francis at Noon on Christmas Day

And here is the message that Pope Francis promounced at noon today, his Urbi et Orbi message, "to the City and to the World."

Pope Francis’ Christmas Day Urbi et Orbi Message

At noon today from the central loggia of St. Peter’s Basilica, Pope Francis addressed the following Christmas Message to a crowd of approximately 40,000 people gathered in St. Peter’s Square.

Dear Brothers and Sisters, Happy Christmas!

Today the Church once again experiences the wonder of the Blessed Virgin Mary, Saint Joseph and the shepherds of Bethlehem, as they contemplate the newborn Child laid in a manger: Jesus, the Saviour.

On this day full of light, the prophetic proclamation resounds: “For to us a child is born, To us a son is given. And the government will be upon his shoulder; and his name will be called “Wonderful Counsellor, Mighty God, Everlasting Father, Prince of Peace.” (Is 9:6)

The power of this Child, Son of God and Son of Mary, is not the power of this world, based on might and wealth; it is the power of love. It is the power which created the heavens and the earth, which gives life to all creation: to minerals, plants and animals; it is the force which attracts man and woman, and makes them one flesh, one single existence; it is the power which gives new birth, pardons faults, reconciles enemies, and transforms evil into good.

It is the power of God. This power of love led Jesus Christ to strip himself of his glory and become man; it led him to give his life on the cross and to rise from the dead. It is the power of service, which inaugurates in our world the Kingdom of God, a kingdom of justice and peace.

For this reason, the birth of Jesus was accompanied by the angels’ song as they proclaimed: “Glory to God in the highest, And on earth peace among men with whom he is pleased!” (Lk 2:14).

Today this message goes out to the ends of the earth to reach all peoples, especially those scarred by war and harsh conflicts that seem stronger than the yearning for peace.

Peace to men and women in the war-torn land of Syria, where far too much blood has been spilled.

Above all in the city of Aleppo, site of the most awful battles in recent weeks, it is most urgent that assistance and support be guaranteed to the exhausted civil populace, with respect for humanitarian law. It is time for weapons to be still forever, and the international community to actively seek a negotiated solution, so that civil coexistence can be restored in the country.

Peace to women and men of the beloved Holy Land, the land chosen and favoured by God. May Israelis and Palestinians have the courage and the determination to write a new page of history, where hate and revenge give way to the will to build together a future of mutual understanding and harmony.

May Iraq, Libya and Yemen – where their peoples suffer war and the brutality of terrorism – be able once again to find unity and concord.

Peace to the men and women in various parts of Africa, especially in Nigeria, where fundamentalist terrorism exploits even children in order to perpetrate horror and death.

Peace in South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, so that divisions may be healed and all people of good will may strive to undertake the path of development and sharing, preferring the culture of dialogue to the mindset of conflict.

Peace to women and men who to this day suffer the consequences of the conflict in Eastern Ukraine, where there is urgent need for a common desire to bring relief to the civil population and to put into practice the commitments which have been assumed.

We implore harmony for the dear people of Colombia, which seeks to embark on a new and courageous path of dialogue and reconciliation.

May such courage also motivate the beloved country of Venezuela to undertake the necessary steps to put an end to current tensions, and build together a future of hope for the whole population.

Peace to all who, in different areas, are enduring sufferings due to constant dangers and persistent injustice.

May Myanmar consolidate its efforts to promote peaceful coexistence and, with the assistance of the international community, provide necessary protection and humanitarian assistance to all those who gravely and urgently need it.

May the Korean peninsula see the tensions it is experiencing overcome in a renewed spirit of cooperation.

Peace to those who have lost a person dear to them as a result of brutal acts of terrorism, and to those who have sown fear and death into the hearts of so many countries and cities.

Peace – not merely the word, but a real and concrete peace – to our abandoned and excluded brothers and sisters, to those who suffer hunger and to all the victims of violence.

Peace to exiles, migrants and refugees, to all those who in our day are subject to human trafficking.

Peace to the peoples who suffer because of the economic ambitions of the few, because of the sheer greed and the idolatry of money, which leads to slavery.

Peace to those affected by social and economic unrest, and to those who endure the consequences of earthquakes or other natural catastrophes.

Peace to the children, on this special day on which God became a child, above all those deprived of the joys of childhood because of hunger, wars or the selfishness of adults.

Peace on earth to men and women of goodwill, who work quietly and patiently each day, in their families and in society, to build a more humane and just world, sustained by the conviction that only with peace is there the possibility of a more prosperous future for all.

Dear brothers and sisters,

“For to us a child is born, to us a son is given”: he is the “Prince of peace”. Let us welcome him!

[after the Blessing]

To you, dear brothers and sisters, who have gathered in this Square from every part of the world, and to those in various countries who are linked to us by radio, television and other means of communication, I offer my greeting.

On this day of joy, we are all called to contemplate the Child Jesus, who gives hope once again to every person on the face of the earth. By his grace, let us with our voices and our actions give witness to solidarity and peace.

Merry Christmas to all!

Christmas Eve 2016

“Do not be afraid. I bring you news of great joy. Today a Saviour has been born for you: he is Christ the Lord.”

|

| Midnight Mass in our monastery in Pachacamac |

We have just heard from St Luke’s Gospel how Jesus was born. Before that we heard the prophecy of Isaiah, who spoke of “a child born for us, a son given to us.” In fact “the people that walked in darkness has seen a great light.” God “has made their gladness greater, their joy increase.” St Paul, writing to Titus, looks forward to the Second Coming, the return of Christ at the end of time. “We are waiting in hope for the blessing which will come with the Appearing of the glory of our great God and saviour Jesus Christ.” So tonight, we look back with rejoicing to the birth of the Messiah in a stable at Bethlehem, a child laid in a manger, fragile and powerless, while at the same time we look forward to his coming in glory to be our merciful Judge and to inaugurate once and for all the Kingdom of his Father. The Babe of Bethlehem, whom we adore tonight together with Mary and Joseph, the shepherds, the angels and the whole of creation, is the Saviour who died on a Cross, was raised from the dead and has poured out the Holy Spirit on all who believe him to be the Son of God.

The message of the angels, “Do not be afraid,” is what we long to hear tonight, as fear grips the hearts of men, women and children throughout a world torn apart by war, hatred, persecution and terrorism, a world that seems to be spinning out of control and in which we often feel helpless. It was in such a world that Christ was born two thousand years’ ago. Had Mary and Joseph not escaped into exile in Egypt as refugees, the baby Jesus would have died at the hands of King Herod in the massacre of the Holy Innocents. Why did God become man in the Virgin’s womb? Why was he born, a man like us in all things but sin? Why his Passion, Death and Resurrection? Jesus himself gives the answer: “It is not those who are well who need the doctor, but the sick. I have come to call not the just, but sinners to repentance.” We are all sinners and those words apply to us, yet we must look outside ourselves as well as within. It is right to prepare our hearts for Christ to be born again within us. We must commit ourselves to Jesus and the Gospel in a radical way, but he came not only for us, the chosen few as it were, but for those who need him most.

Where does Jesus wish to be born tonight? Wherever there is fear and people are terrified, bewildered and confused. Wherever there is suffering and pain, wherever there is death and destruction. Wherever men have turned away from the love of God and hatred has taken possession of their hearts. Wherever there is a lost sheep or a prodigal son. Wherever hope is lost and the light snuffed out. Just as there is no room in the inn for Mary to give birth, so men’s hearts are tight shut for fear of Christ knocking at the door and asking to enter. Even so, Christ wants to be born wherever his light is needed, and with it healing and forgiveness, God’s mercy that can bring about reconciliation and peace. He longs to be born tonight in the heart of the terrorist and despot, the warmonger and murderer, as well as in the hearts of their victims, the innocent and pure.

Now if Jesus has come to call the sinner to repentance, then it is our duty as Christians to share in his work of forgiveness and compassion. Let us vow tonight, before the altar and the crib, to do all we can to bring the light, hope and peace of Christmas and the truth and joy of Christ’s Gospel into the fear and darkness of our world. For God all things are possible: with the gentle power of Jesus and the grace of the Holy Spirit, nothing is impossible. Christ wants all men to be saved and he wants us to do something about it.

“Do not be afraid. I bring you news of great joy. Today a Saviour has been born for you: he is Christ the Lord.”

On behalf of Fr Prior and the monastic Community, I wish you all a very happy and holy Christmas.

Christmas Day 2016

At Midnight Mass, we heard from St Luke’s Gospel how Jesus came to be born. At the Dawn Mass, St Luke described the visit of the shepherds, how “they found Mary and Joseph, and the baby lying in the manger.” There they become the first evangelists, as they repeat for everyone to hear, what the angels had told them, “Today in the town of David a saviour has been born to you; he is Christ the Lord.” We are told that, “Mary treasured all these things and pondered them in her heart.” Our Lady, of course, had had a long time to ponder what was going on, ever since that day when the Angel Gabriel appeared to her to announce that, through the working of the Holy Spirit, she would conceive and bear a son, whom she was to name Jesus. “He will be great and will be called Son of the Most High. The Lord God will give him the throne of his ancestor David; he will rule over the house of Jacob for ever and of his kingdom there will be no end.” The shepherds confirmed what she already knew, that she was the Mother of God and that, in the mystery of the Incarnation, God had become man.

Like any other woman who becomes a mother, Mary treasured every moment: the conception of her child, each stage of pregnancy, even today a dangerous time for many women, and finally the birth of her firstborn in a stable at Bethlehem, the child now lying in the manger. But what she pondered, she never told; we can but imagine. The Church, each one of us here this morning, together with Mary, treasures what we know and have experienced of the Nativity, and we like Mary ponder, in fact the Church has pondered nothing else ever since, for Christ is the very centre of our faith, he is our life. In the Letter to the Hebrews, we heard, “He is the radiant light of God’s glory and the perfect copy of his nature, sustaining the universe by his powerful command.” In the responsorial Psalm we sang, “All the ends of the earth have seen the salvation of our God.” However, it is the Prologue to St John’s Gospel, this morning’s Gospel, which possibly reveals to us the depth of Mary’s pondering. Remember how Jesus had said to Mary in the agony of the crucifixion, “Woman, behold thy son,” and how he had said to the beloved disciple, “Behold thy mother.” Did Mary share with John the inmost thoughts of her heart? There is much in his gospel that could be the fruit of Our Lady’s experience.

On Christmas morning, during the Mass of the Day, we read and reflect on the profound truths revealed to us in the Scriptures, above all in the Prologue written by the great Theologian St John. “In the beginning was the Word: the Word was with God and the Word was God.” Through the Word, all things come into being, for he is both life and light, a light that cannot be overcome by darkness. He is the only Son of the Father, who comes into the world and becomes flesh. Mary understood her part in God’s plan of salvation, a plan that was his from all eternity. Although rejected by his own, the Word made flesh enables all who accept him to become children of God, sharing in God’s fullness, a gift reflecting God ‘s enduring love. “Indeed, from his fullness we have all received grace in return for grace, since, though the Law was given through Moses, grace and truth have come through Jesus Christ.” He who is both light and life, the Word made flesh, God incarnate, Jesus Christ, the son of Mary, the Babe lying in the manger, has come that we might have life and have it to the full. He is the way, the truth and the life, and the only source of grace, through the outpouring of the Holy Spirit. In Christ, we see God and know him. “It is the only Son, who is nearest to the Father’s heart, who has made him known.”

As you ponder with Mary today on the Mystery of the Incarnation, may your hearts be filled with grace and truth.

On behalf of Fr Prior and the Monastic Community, I wish you all a very happy and a holy Christmas.

Christmas Day 2016

HOMILY FOR CHRISTMAS DAY

At Midnight Mass, we heard from St Luke’s Gospel how Jesus came to be born. At the Dawn Mass, St Luke described the visit of the shepherds, how “they found Mary and Joseph, and the baby lying in the manger.” There they become the first evangelists, as they repeat for everyone to hear, what the angels had told them, “Today in the town of David a saviour has been born to you; he is Christ the Lord.” We are told that, “Mary treasured all these things and pondered them in her heart.” Our Lady, of course, had had a long time to ponder what was going on, ever since that day when the Angel Gabriel appeared to her to announce that, through the working of the Holy Spirit, she would conceive and bear a son, whom she was to name Jesus. “He will be great and will be called Son of the Most High. The Lord God will give him the throne of his ancestor David; he will rule over the house of Jacob for ever and of his kingdom there will be no end.” The shepherds confirmed what she already knew, that she was the Mother of God and that, in the mystery of the Incarnation, God had become man.

Like any other woman who becomes a mother, Mary treasured every moment: the conception of her child, each stage of pregnancy, even today a dangerous time for many women, and finally the birth of her firstborn in a stable at Bethlehem, the child now lying in the manger. But what she pondered, she never told; we can but imagine. The Church, each one of us here this morning, together with Mary, treasures what we know and have experienced of the Nativity, and we like Mary ponder, in fact the Church has pondered nothing else ever since, for Christ is the very centre of our faith, he is our life. In the Letter to the Hebrews, we heard, “He is the radiant light of God’s glory and the perfect copy of his nature, sustaining the universe by his powerful command.” In the responsorial Psalm we sang, “All the ends of the earth have seen the salvation of our God.” However, it is the Prologue to St John’s Gospel, this morning’s Gospel, which possibly reveals to us the depth of Mary’s pondering. Remember how Jesus had said to Mary in the agony of the crucifixion, “Woman, behold thy son,” and how he had said to the beloved disciple, “Behold thy mother.” Did Mary share with John the inmost thoughts of her heart? There is much in his gospel that could be the fruit of Our Lady’s experience.

On Christmas morning, during the Mass of the Day, we read and reflect on the profound truths revealed to us in the Scriptures, above all in the Prologue written by the great Theologian St John. “In the beginning was the Word: the Word was with God and the Word was God.” Through the Word, all things come into being, for he is both life and light, a light that cannot be overcome by darkness. He is the only Son of the Father, who comes into the world and becomes flesh. Mary understood her part in God’s plan of salvation, a plan that was his from all eternity. Although rejected by his own, the Word made flesh enables all who accept him to become children of God, sharing in God’s fullness, a gift reflecting God ‘s enduring love. “Indeed, from his fullness we have all received grace in return for grace, since, though the Law was given through Moses, grace and truth have come through Jesus Christ.” He who is both light and life, the Word made flesh, God incarnate, Jesus Christ, the son of Mary, the Babe lying in the manger, has come that we might have life and have it to the full. He is the way, the truth and the life, and the only source of grace, through the outpouring of the Holy Spirit. In Christ, we see God and know him. “It is the only Son, who is nearest to the Father’s heart, who has made him known.”

As you ponder with Mary today on the Mystery of the Incarnation, may your hearts be filled with grace and truth.

On behalf of Fr Prior and the Monastic Community, I wish you all a very happy and a holy Christmas.

Sir John BetjemanChristmasThe bells of waiting Advent ring,The Tortoise stove is lit againAnd lamp-oil light across the nightHas caught the streaks of winter rainIn many a stained-glass window sheenFrom Crimson Lake to Hookers Green.The holly in the windy hedgeAnd round the Manor House the yewWill soon be stripped to deck the ledge,The altar, font and arch and pew,So that the villagers can say'The church looks nice' on Christmas Day.Provincial Public Houses blaze,Corporation tramcars clang,On lighted tenements I gaze,Where paper decorations hang,And bunting in the red Town HallSays 'Merry Christmas to you all'.And London shops on Christmas EveAre strung with silver bells and flowersAs hurrying clerks the City leaveTo pigeon-haunted classic towers,And marbled clouds go scudding byThe many-steepled London sky.And girls in slacks remember Dad,And oafish louts remember Mum,And sleepless children's hearts are glad.And Christmas-morning bells say 'Come!'Even to shining ones who dwellSafe in the Dorchester Hotel.And is it true? And is it true,This most tremendous tale of all,Seen in a stained-glass window's hue,A Baby in an ox's stall ?The Maker of the stars and seaBecome a Child on earth for me ?And is it true ? For if it is,No loving fingers tying stringsAround those tissued fripperies,The sweet and silly Christmas things,Bath salts and inexpensive scentAnd hideous tie so kindly meant,No love that in a family dwells,No carolling in frosty air,Nor all the steeple-shaking bellsCan with this single Truth compare -That God was man in PalestineAnd lives today in Bread and Wine.

© by owner. provided at no charge for educational purposes

What Is This Word?

The incomprehensible, intimate Christmas story.

by

N. T. Wright

DECEMBER 21, 2006

One of the greatest journalists of the last generation, Bernard Levin, described how, when he was a small boy, a great celebrity came to visit his school. The headmaster, perhaps wanting to impress, called the young Levin to the platform in front of the whole school. The celebrity, perhaps wanting to be kind, asked the little boy what he'd had for breakfast.

"Matzobrei," replied Levin. A typical central European Jewish dish, Matzobrei is made of eggs fried with matzo wafers, brown sugar, and cinnamon. Levin's immigrant mother had continued to make it even after years of living in London. To him, it was a perfectly ordinary word for a perfectly ordinary meal.

But the celebrity, ignorant of such cuisine, thought he'd misheard. He repeated his question. Levin, now puzzled and anxious, gave the same answer. The celebrity looked concerned and glanced at the headmaster: What is this word he's saying? The headmaster, adopting a there-there-little-man tone, asked Levin once more what he had had for breakfast. Dismayed, not knowing what he'd done wrong, and wanting to burst into tears, the boy said once more the only answer he could honestly give: "Matzobrei." After an exchange of incredulous glances on the platform, the terrified little boy was sent back to his place. The incident was never referred to again, but to him it was a horrible ordeal.

A Jewish word spoken to an uncomprehending world; a child's word spoken to uncomprehending adults; a word for a food of which others were unaware—it all feels very Johannine. "In the beginning was the Word … and the Word was made flesh" (John 1:1, 14). We are so used to that passage, the great cadences, the solemn but glad message of the Incarnation, that we risk skipping over the incomprehensibility, the oddness, the almost embarrassing strangeness of the Word. "The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness didn't comprehend it; the world was made through him and the world didn't know him; he came to his own, and his own didn't receive him" (John 1:5, 10–11).

John is saying two things simultaneously in his prologue (two hundred things, actually, but I'll concentrate on two): First, that the Incarnation of the eternal Word was the event for which the whole of creation had been waiting all along; second, that creation and even the people God were quite unready for this event. Jew and Gentile alike, upon hearing of this strange Word, cast anxious glances at one another, like the celebrity and the headmaster hearing a little boy telling the truth in a language they didn't understand.

That is the puzzle of Christmas. John's prologue is designed to stay in the mind and heart throughout the subsequent story. Never again in the Gospel of John is Jesus referred to as "the Word," but we are meant to look at each scene—the call of the first disciples, the changing of water into wine, the confrontation with Pilate, the Crucifixion, and the Resurrection—and think to ourselves: This is what it looks like when the Word becomes flesh. Or, if you like: Look at this man of flesh and learn to see the living God.

But watch what happens as it all plays out. He comes to his own, and his own don't receive him. The light shines in the darkness, and though the darkness can't overcome it, the darkness sure tries. He speaks the truth, the plain and simple words, like the little boy saying what he had for breakfast, and Caiaphas and Pilate, uncomprehending, can't decide whether he's mad or wicked or both.

Though Jesus is never again referred to as the Word of God, we find the theme transposed throughout the Gospel with endless variations. The Living Word speaks living words, and the reaction is the same. "This is a hard word," say his followers when he tells them that he is the bread come down from heaven (John 6:60). "What is this word?" asks the puzzled crowd in Jerusalem (John 7:36). "My word finds no place in you," says Jesus, "because you can't hear it" (John 8:37, 43). "The word I spoke will be their judge on the last day," he insists (John 12:48), as the crowds reject him.

When Pilate hears the word, says John, he is afraid, since the word in question is Jesus' reported claim to be the Son of God (John 19:8). Unless we recognize this strange, dark strand running through the Gospel, we will domesticate John's masterpiece (just as we're always in danger of domesticating Christmas) and think it's only about comfort and joy. In truth, it's also about incomprehension, rejection, darkness, denial, stopped ears, and judgment. Christmas is not about the living God coming to tell us everything's all right. John's Gospel isn't about Jesus speaking the truth and everyone saying "Of course! Why didn't we realize it before?" It is about God shining his clear, bright torch into the darkness of our world, our lives, our hearts, our imaginations—and the darkness not comprehending it. It's about God, God as a little child, speaking words of truth, and nobody knowing what he's talking about.

You may be aware of that puzzlement, that incomprehension, that sense of a word being spoken which seems like it ought to mean something but which remains opaque to you. If that's the point you are at, the Good News is that along with this theme of incomprehension and rejection is a parallel theme of people hearing and receiving Jesus' words, believing them and discovering, as he says, that they are spirit and life (John 6:63). "As many as received him, to them he gave the right to become God's children, who were born not of human will or flesh, but of God" (John ?:?). "If you abide in my words, you will know the truth and the truth shall set you free" (John 8:?). "If anyone keeps my words, that person will never see death" (John 8:51). "You are already made clean by the word which I have spoken to you" (John 15:3).

Don't imagine that the world divides naturally into those who can understand what Jesus is saying and those who can't. By ourselves, none of us can. Jesus was born into a world where everyone was deaf and blind to him. But some, in fear and trembling, have allowed his words to challenge, rescue, heal, and transform them. That is what's offered at Christmas, not a better-focused religion for those who already like that sort of thing, but a Word which is incomprehensible in our language but which, when we learn to hear, understand, and believe it, will transform our whole selves with its judgment and mercy.

Out of the thousands of things that follow directly from this reading of John, I choose three as particularly urgent.

First, John's view of the Incarnation, of the Word becoming flesh, strikes at the very root of the liberal denial which characterized mainstream theology thirty years ago and whose long-term effects are still with us. I grew up hearing lectures and sermons declaring that the idea of God becoming human was a categorical error. No human being could be divine; Jesus must therefore have been simply a human being, albeit (here the headmaster pats the little boy on the head) a very brilliant one. Jesus points to God, but he isn't actually God. A generation later, growing straight out of that school of thought, a clergyman wrote to me saying that the church doesn't know anything for certain. Remove the enfleshed and speaking Word from the center of your theology, and gradually the whole thing unravels, until all you're left with is the theological equivalent of the grin on the Cheshire Cat: a relativism whose only moral principle is that there are no moral principles, no words of judgment (because nothing is really wrong, except saying that things are wrong), no words of mercy (because you're all right as you are, so all you need is affirmation).

That's where our society stands right now, and John's Christmas message issues a sharp and timely reminder to relearn the difference between mercy and affirmation, between a Jesus who both embodies and speaks God's word of judgment and grace and a homemade Jesus who gives us good advice about discovering who we really are. No wonder John's Gospel has been so unfashionable in many circles.

There is a fad in some quarters about a "theology of incarnation," meaning that our task is to discern what God is doing in the world and to do it with him. But that is only half the truth, and the wrong half to start with. John's theology of the Incarnation is about God's Word coming as light into darkness, as a hammer that breaks the rock into pieces, as a fresh word of judgment and mercy. You might as well say that an incarnational missiology is about discovering what God is saying no to today and finding out how to say it with him. That was the lesson Barth and Bonhoeffer had to teach in Germany in the 1930s, and it's all too relevant as today's world becomes simultaneously more liberal and more totalitarian. This Christmas, get real, get Johannine, and listen again to the strange words spoken by the Word made flesh.

Second, John's prologue by its structure reaffirms the order of Creation at the point where it is being challenged today. John consciously echoes the first chapter of Genesis: "In the beginning God made heaven and earth; in the beginning was the Word" (v. ?). When the Word becomes flesh, heaven and earth are joined together at last, as God always intended. But the Creation story, which begins with the duality of heaven and earth, reaches its climax in the duality of male and female. When heaven and earth are joined together in Jesus Christ, the glorious intention for the whole of Creation is unveiled, reaffirming the creation of male and female in God's image. There is something about the enfleshment of the Word in John 1 that stands parallel to Genesis 1 and speaks of Creation fulfilled. We see what's going on: Jesus Christ has come as the Bridegroom, the one for whom the Bride has been waiting.

Not for nothing is Jesus' first sign to transform a wedding from disaster to triumph. Not for nothing do we find a man and a woman at the foot of the Cross. The same incipient gnosticism which says that true religion is about "discovering who we really are" is all too ready to say that who we really are may have nothing to do with being physically created as male or female. But the Christmas message is about the redemption of God's good world, his wonderful Creation, so that it can be the glorious thing it was made to be. This word is strange, even incomprehensible, in today's culture. But if you have ears to hear, then hear it.

Third, we return to the meal, the food whose name is strange, forbidding, even incomprehensible to those outside, but the most natural thing to those who know it. The little child comes and speaks to us of food that he offers: himself, his own body and blood. It is a hard saying, and those of us who know it well may need to remind ourselves just how hard it is, in case we have been dulled by familiarity into supposing that it's easy and undemanding. It isn't. It is the Word which judges the world and saves the world, the Word now turned into flesh, into matzo, Passover bread, the bread which is the flesh of the Christ child, given for the life of the world.

Listen, because the incomprehensible Word, the child, speaks to you. Don't patronize him; don't reject him; don't sentimentalize him. Learn the language within which he makes sense. And come to the table to enjoy the breakfast, the breakfast which is he himself, the Word made flesh, the Life which is our life, our light, our glory.

N. T. Wright was bishop of Durham. This article is adapted from Wright's Christmas 2005 Eucharist sermon, delivered at the Cathedral Church of Christ.Nicholas Thomas Wright (born 1 December 1948) is a leading British New Testament scholar and retired Anglican bishop. In academia, he is published as N. T. Wright, but is otherwise known as Tom Wright. Between 2003 and his retirement in 2010, he was the Bishop of Durham. He then became Research Professor of New Testament and Early Christianity at St Mary’s College in the University of St Andrews in Scotland.

The Messiah by G. Handel

TWO CHRISTMAS HOMILIES BY ABBOT PAUL

TWO CHRISTMAS HOMILIES BY ABBOT PAUL

There will be more on Christmas Day. Before January 7th we shall offer our Eastern Byzantine Rite readers a happy Christmas like this one. Any suggestions what should be included?

No comments:

Post a Comment