Source: Praying in the Rain

my source: Pravmir.com

03 SEPTEMBER 2015

Learning the Prayer of The Heart

St. Ignatius (Brianchaninov): “Learn to Pray to God in the Right Way”

In 1851, an anonymous monk on Mount Athos wrote a book on prayer. The title of the book has been translated as The Watchful Mind: Teachings on the Prayer of the Heart. It is a book that I cannot recommend for most people because, like much classic Orthodox spiritual writing (the Philokalia, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, The Ascetical Homilies of St. Isaac the Syrian, to name a few), it was written for people pursuing the spiritual life, a life in communion with God, in a very specific monastic setting, a setting that exists in very few places in the world today, or some might say—indeed have said—in a setting that does not exist at all in the world any more.

And yet, these texts are nonetheless compelling for us because they bear witness to a relationship with God, an intensity of relationship with God, that many people in the world today long for.

And yet, these texts are nonetheless compelling for us because they bear witness to a relationship with God, an intensity of relationship with God, that many people in the world today long for.

The big danger in reading these books is twofold. The first is delusion: to think you have attained to the heights of which these holy writers speak. The second (and most common in my experience) is despondency as you realize that you cannot discipline yourself to attain even to what these writers describe as the preliminary conditions for noetic prayer. Both delusion and despondency are real possibilities for those who venture into these texts without care and guidance. Nonetheless, like treasure hunters, some of us are lured into these texts seeking nuggets of helpful guidance in prayer, nuggets that can be applied in the world, in the fallen culture and capitalist economic realities we find ourselves in. Even in the mud and mire, some of us still long to glimpse the flowers that only grow in alpine meadows.

And here is the good news: it is possible to find wise advice and nuggets of helpful insight in these books written for advanced strugglers in spiritual prayer, advice and insight that is not only helpful for those great athletes of prayer, but also for us in the beginner’s class, those of us in the world, distracted by cares of family and of making a living. Even here in the world, we can begin to pray and experience some of the low-hanging fruits of prayer.

We must take care, however, to remember that we are barely beginners. If God grants us an experience in prayer that overwhelms us, it’s only a token to encourage us on the way, not evidence of maturity. And, we must never forget that as beginners we can be easily deceived (like children enticed by candy from strangers), so we must not hide what we think God is showing us from our spiritual fathers and mothers. The evil one works in darkness. Revealing our thoughts to someone else, someone we respect, whose evaluation of our experiences we will respect, this is our main weapon against delusion. Similarly, as beginners, we must not despair when we see how far we are from the spiritual heights described in these holy books. Neither do we need to become despondent at our slothfulness or the intensity of the attack of our passions.

We are beginners, babies in the spiritual struggle. And just as babies can suddenly fall into a temper tantrum and just as suddenly fall out, we too are just beginning to learn to recognize and battle against the passions.

We are beginners, babies in the spiritual struggle. And just as babies can suddenly fall into a temper tantrum and just as suddenly fall out, we too are just beginning to learn to recognize and battle against the passions.

In fact, it is here, in learning to resist the passions, that we can learn one of the fundamental lessons that leads to prayer of the heart. In Discourse 3 of The Watchful Mind, the unknown monk of Mount Athos tells the stories of two men and how the demons and passion—the very enemies of prayer—became the means by which they learned to pray.

In truth, when one of the fathers was asked about from where he learned noetic prayer, he said he learned it from the demons. And when another father was asked about this same subject, he said that he learned it from beardless youths. These words might seem strange, but they are not. The first, by forcing his heart with the prayer in order to drive away approaching demons, advanced in the prayer so much that he discovered the perfect method of the prayer. So the demons were the cause of this discovery, and he rightly said that he learned the prayer from the demons. The other, seeing beardless youths, feared that his heart might become impure from some evil thought and a wicked consent of the heart, and so he forced his heart in the prayer so much that he too found the perfect method of the noetic prayer of the heart. For this reason, then, both of them answered correctly.

As it turns out, the very demons and passions that seek to drive a wedge between us and God, if we will fight against them with prayer in our hearts, can be the means of teaching us effective prayer. The demons that the writer is speaking of are fear-generating demons. In the text he talks about how demons will suggest fearsome thoughts to us about what could or might happen if we proceed in our righteous intention. These thoughts quickly stimulate our bodily responses so that we begin to sweat or shake or feel our hearts beating quickly. It is specifically these fear-generating demons that the writer is speaking of when he says that demons can teach us to pray. When our minds are attacked by a flood of fearsome thoughts, we can, as the monk did, begin to force our hearts to say the prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me.” We can repeat this prayer with every breath, forcing our hearts and minds to pay attention to nothing but this prayer. If we will do this, then we will discover that even the demons, manifested to us in thoughts creating in us crippling fear, even these demons can be the fuel that generates the beginnings of pure prayer in our hearts.

And then there is the example of the temptation of beardless youths. Although this is a specific reference to homosexual passion, any driving passion can produce the same effect in anyone who wants to respond to the passion with prayer. When I was a young university student striving to be holy as best as I understood it in those days, I used to hate the month of May because the warmer weather was the signal to all of the young women to take off most of their clothes. I didn’t know about the Jesus prayer in those days, so I used to walk down the halls of my university staring at the ceiling trying to avoid seeing women’s bodies and the passionate thoughts and feelings that would be aroused in me. I can tell you from experience, that the Jesus prayer works much better than walking down the hallway staring at the ceiling (and you also bump into fewer people and things).

It doesn’t matter what kind of passion drives you crazy: envy, anger, lust, greed, selfishness—even depression or despair. All of the passions can teach us to pray if we really want to be free from the passion and we really want to pray. A metaphor I ran across once that really captures one of the ways that I have learned to use the Jesus prayer is that of using the Jesus Prayer as a stick to beat away unwanted thoughts, to beat away the demons. When I find myself under attack, when unwanted thoughts bombard me or when sinful images invade my mind and I cannot get rid of them easily, then the only weapon I seem to have is the Jesus prayer said forcefully in my heart and even loudly with my mouth. When I’m not in a private place, I will sometimes take a walk or even drive my car so that I can pray forcefully and out loud, “Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me!”

I know from what I have read and from what I have heard from a few holy people I have met over the years that there are heights of prayer and nearness to God that are way beyond anything I am likely to ever experience, largely because I am not a monastic and because I am not a very diligent person. Nonetheless, there are crumbs that fall from the table of very holy men and women, nuggets of spiritual insight and techniques and experiences of prayer that even we in the world can eat up and profit from. Using the Jesus Prayer as a stick to beat away the unwanted thoughts of demons and the passions that can overpower us is one of these crumbs from the table. And if we will do it—not just think about it, but do it—if we will pray when we are attacked by fears or passions, then we will discover that this little crumb of insight may be all we need to begin to overcome the passions and to grow in virtue and in the knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. It may just be for us the beginning of the Prayer of the Heart.

Prayer and the Absence of God

Source: St. Lawrence Orthodox Church

my source: Pravmir.com

There is a situation in which we have no right to complain of the absence of God, because we are a great deal more absent than He ever is.

METROPOLITAN ANTHONY OF SOUROZH | 02 FEBRUARY 2015

At the outset of learning to pray there is one very important problem: God seems to be absent. Obviously I am not speaking of a real absence—God is never really absent—but of the sense of absence which we have. We stand before God and we shout into an empty sky, out of which there is no reply. We turn in all directions and He is not to be found. What ought we to think of this situation?

First of all, it is very important to remember that prayer is an encounter and a relationship, a relationship which is deep, and this relationship cannot be forced either on us or on God. The fact that God can make Himself present or can leave us with the sense of His absence is part of this live and real relationship. If we could mechanically draw Him into an encounter, force Him to meet us, simply because we have chosen this moment to meet Him, there would be no relationship and no encounter. We can do that with an image, with the imagination, or with the various idols we can put in front of us instead of God; we can do nothing of the sort with the living God, any more than we can do it with a living person.

A relationship must begin and develop in mutual freedom. If you look at the relationship in terms of mutual relationship, you will see that God could complain about us a great deal more than we about Him. We complain that He does not make Himself present to us for the few minutes we reserve for Him, but what about the twenty-three and a half hours during which God may be knocking at our door and we answer, ‘I am busy, I am sorry,’ or when we do not answer at all because we do not even hear the knock at the door of our heart, of our minds, of our conscience, of our life. So there is a situation in which we have no right to complain of the absence of God, because we are a great deal more absent than He ever is.

The second very important thing is that a meeting face to face with God is always a moment of judgment for us. We cannot meet God in prayer or in meditation or in contemplation and not be either saved or condemned. I do not mean this in major terms of eternal damnation or eternal salvation already given and received, but it is always a critical moment, a crisis. ‘Crisis’ comes from the Greek and means ‘judgment.’ To meet God face to face in prayer is a critical moment in our lives, and thanks be to Him that He does not always present Himself to us when we wish to meet Him, because we might not be able to endure such a meeting. Remember the many passages in Scripture in which we are told how bad it is to find oneself face to face with God, because God is power, God is truth, God is purity. Therefore, the first thought we ought to have when we do not tangibly perceive the divine presence, is a thought of gratitude. God is merciful; He does not come in an untimely way. He gives us a chance to judge ourselves, to understand, and not to come into His presence at a moment when it would mean condemnation.

Look at the various passages in the Gospel. People much greater than ourselves hesitated to receive Christ. Remember the centurion who asked Christ to heal his servant. Christ said, ‘I will come,’ but the centurion said, ‘No, don’t. Say a word and he will be healed.’ Do we do that? Do we turn to God and say, ‘Don’t make yourself tangibly, perceptively present before me. It is enough for You to say a word and I will be healed. It is enough for You to say a word and things will happen. I do not need more for the moment.’ Or take Peter in his boat after the great catch of fish, when he fell on his knees and said, ‘Leave me, O Lord, I am a sinner.’ He asked the Lord to leave his boat because he felt humble—and he felt humble because he had suddenly perceived the greatness of Jesus. Do we ever do that? When we read the Gospel and the image of Christ becomes compelling, glorious, when we pray and we become aware of the greatness, the holiness of God, do we ever say, ‘I am unworthy that He should come near me?’ Not to speak of all the occasions when we should be aware that He cannot come to us because we are not there to receive Him. We want something from Him, not Him at all. Is that a relationship? Do we behave in that way with our friends? Do we aim at what friendship can give us or is it the friend whom we love? Is this true with regard to the Lord?

Let us think of our prayers, yours and mine; think of the warmth, the depth and intensity of your prayer when it concerns someone you love or something which matters to your life. Then your heart is open, all your inner self is recollected in the prayer. Does it mean that God matters to you? No, it does not. It simply means that the subject matter of your prayer matters to you. For when you have made your passionate, deep, intense prayer concerning the person you love or the situation that worries you, and you turn to the next item, which does not matter so much—if you suddenly grow cold, what has changed? Has God grown cold? Has He gone? No, it means that all the elation, all the intensity in your prayer was not born of God’s presence, of your faith in Him, of your longing for Him, of your awareness of Him; it was born of nothing but your concern for him or her or it, not for God. It is we who make ourselves absent, it is we who grow cold the moment we are no longer concerned with God.

From Beginning to Pray by Met. Anthony Bloom

Mystery, Beauty and the Jesus Prayer

Source: Saint Aidan Orthodox Church, Canadamy source: pravmir.com

|

| Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoyevsky |

A friend and fellow pastor recently shared his opinion that the Orthodox Church in Cranbrook exists to offer a testimony to the dimensions of beauty and mystery that are too easily forgotten in post-modern Christianity. I would agree. Dostoevsky once said, “Beauty will save the world.” He may well have been speaking of his own Orthodox Christian faith, which places both beauty and mystery at the heart of its spiritual culture and worship.

What is beauty? It is not primarily a set of standards by which society deems certain things or people more pleasing to eye than others. Beauty, rather, is the glory of God shining in the lives of His children. One of the Church Fathers said, “The glory of God is a human being fully alive.” When we live the full, authentic human lives as God created them to be, His glory radiates through us in a way that is unique to each one of us. This radiance is what makes us truly beautiful, regardless of our physical appearance or worldly attributes.

How then do we acquire this beauty in our lives? That’s where mystery comes into play. In the Orthodox tradition, mystery has a very specific meaning, which is suggested in Saint Paul’s Epistle to the Ephesians: “In Him we have redemption through His blood, the forgiveness of our trespasses, according to the riches of His grace, which He lavished upon us, in all wisdom and insight making known to us the mystery of His will, according to His purpose, which He set forth in Christ as a plan for the fullness of time, to unite all things in Him, things in heaven and things on earth.” The mystery of God is nothing less than the divine-human person of Jesus Christ, who unites all things in heaven and on earth to God in Himself.

By encountering the mystery who is Jesus Christ—by putting on Christ, as Saint Paul puts it—we can become “partakers of divine nature.” (2 Peter 1:4) And by participating in His divine life, we enter into His beauty and are reunited with the God who made us for Himself. Dostoevsky’s prophecy is fulfilled: beauty does indeed save the world.

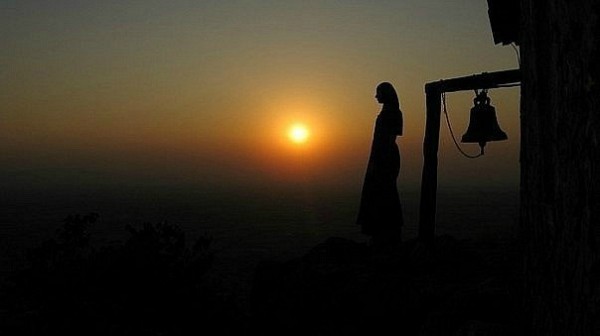

In the 6th century A.D., a monk and writer by the name of John Moschos took his disciple Sophronius on a pilgrimage the ancient holy sites of Christianity. Along the way, they visited a monastery in Egypt, located on the site where Anthony the Great, the founder of monasticism, spent most of his life in a desert cave. They also went to Mount Sinai, where another monastery was built on the site where Moses saw the burning bush.

In making their pilgrimage, the pilgrims’ purpose was simple: to discover a practical way to encounter the mystery of Jesus Christ and become partakers of divine nature. In short, they wanted to know how to be saved. The many Christian spiritual elders that they met on their travels testified to a single practice, which began in the early 3rd century and was later called Hesychia—the Way of Inner Stillness. The practice of Hescychia, according to the elders, involves sitting or standing in a quiet corner, focusing all of your attention on your heartbeat and repeating with attention a single short prayer: “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me.”

John and Sophronius discovered that this simple prayer—called “the Jesus Prayer”—is in fact the heart of ancient Christian spirituality. To this day, Hescyhia remains the most important spiritual practice of the Orthodox Church. The essence of the Jesus Prayer consists in the word “mercy,” which in Orthodox tradition connotes healing and wholeness, rather than pardon or clemency. Daily, moment by moment and heartbeat by heartbeat, we call on Jesus Christ to heal us, binding up the self-inflicted, deadly wounds of sin, and reuniting us with God in love and joy. To invoke Dostoevsky’s idea again, Hesychia allows us to call upon beauty—the glory of God revealed in Jesus Christ—to save us by restoring us to the true humanity for which we were created.

A recent documentary by Dr. Norris Chumley and Rev. Dr. John McGuckin entitled Mysteries of the Jesus Prayer(www.mysteriesofthejesusprayer.com) retraces the steps of those 6th century Christian pilgrims, taking us to the sites they visited, which still function as places of inner stillness today. If you have not had the opportunity to view this remarkable film, I invite you to do so. You will rediscover a two thousand year old secret, ahidden wisdom which speaks to us today with a fresh urgency,showing us how to find true beauty in a time of desolation anddestruction; how to find inner peace in a time of conflict andhatred; and how to be reunited with God and each other in a time of alienation and division.

Fr. Richard Rene is a priest in the Orthodox Church of America, a professional writer and has published a number of poetry, short stories and novels. He also has a podcast on Ancient Faith Radio and posts regular sermons and reflections on his blog Mysterion.

Editor's Note:

In the next post, entitled "Pascha in East and West" by a Greek Metropoltan in America, accompanied by my reply as a Catholic monastic, there is a comparison between Orthodox and Catholic Pascha. As is typical of a certain kind of Orthodox literature, he knows a lot about Orthodoxy and not very much about Catholicism, though he thinks he does. If, perchance, you should read it, remember that I, as a western Catholic monk, am in complete agreement with the above articles and would recommend the teaching on monastic life in the first video below to anyone who wants to know about a monk's life, whether from East or West. I met Archbishop Anthony Bloom a number of times. He was a very saintly man. Like Blessed Mother Teresa of Calcutta, his holiness was evident to those who met him.- Father David Bird o.s.b.

I

No comments:

Post a Comment