Defining Theosis

In his essay, “The Place of Theosis in Orthodox Theology” Andrew Louth suggests that theosis or divinization has a specific doctrinal location in Orthodox theology and that it cannot simply be abstracted away from those doctrines. In this sense, it might be helpful to follow Hallonsten’s distinction between a theme and a doctrine of deification, emphasizing that many (if not most) of the recent proposals claiming to find a doctrine of deification in a historic Protestant figure is probably more of a theme than a doctrine. So, what are these doctrines? I will let Louth summarize:

…I have suggested that deification, by the place it occupies in Orthodox theology, determines the shape of that theology: first, it is a counterpart to the doctrine of the Incarnation, and also anchors the greater arch of the divine economy, which reaches from creation to deification, thereby securing the cosmic dimension of theology; second, it witnesses to the human side of theosis in the transformation involved in responding to the encounter with God offered in Christ through the Holy Spirit – a real change that requires a series ascetic commitment on our part; and finally, deification witnesses to the deeper meaning of the apophatic way found in Orthodox theology, a meaning rooted in the ‘the [sic] repentance of the human person before the face of the living God.'”

He doesn’t explicitly state it, but it seems like Louth is not terribly impressed with all of the “retrievals” that evangelicals (and others) are attempting to construct by adopting a form of theosis. For Louth, it seems, you can’t simply have theosis, you need to have the entire soteriological package – outlined by his four points above. What do we think about this? Is it possible to have a Reformed view of Theosis? I haven’t read Habets on Torrance yet, but I imagine that he must draw some helpful distinctions there. If we disagree with Louth, and I imagine many of us do, what are the necessary and sufficient conditions for a true doctrine of theosis?

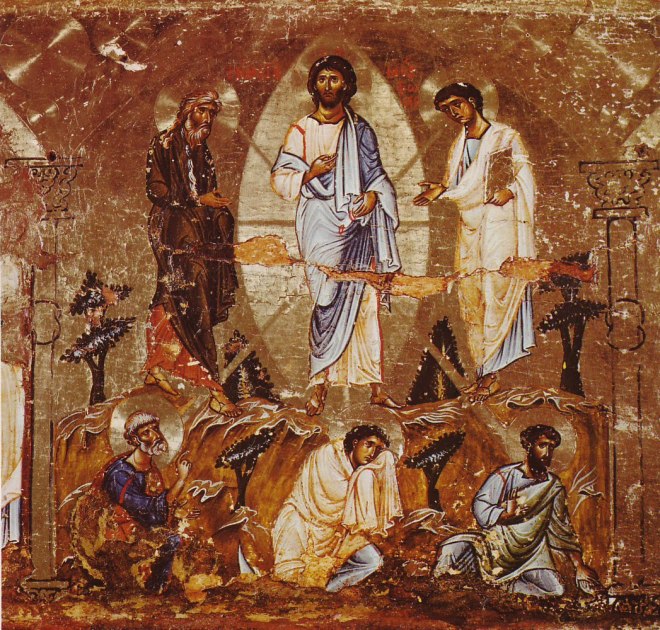

Incarnation and Theosis

Posted by Joe Rawls in incarnation, theosismy source: The Byzantine Anglo-Catholic

Andrew Louth is an Orthodox priest as well as a theology professor at Durham University in England. In his article "The Place of Theosis in Orthodox Theology" (appearing in Partakers of the Divine Nature, Christensen and Wittung, eds, Baker Academic 2007), he outlines the Orthodox understanding of the Incarnation of the Son of God, which is seen as not exclusively a remedy for human sinfulness, but primarily as God's way of uniting in love with his creation. The quote appears on pp 34-35.

Deification, then, has to do with human destiny, a destiny that finds its fulfillment in a face-to-face encounter with God, an encounter in which God takes the initiative by meeting us in the Incarnation, where we behold "the glory as of the Only-Begotten from the Father" (Jn 1:14), "the glory of God in the face of Jesus Christ" (2 Cor 4:6). It is important for a full grasp of what this means to realize that deification is not to be equated with redemption. Christ certainly came to save us, and in our response to his saving action and word we are redeemed; but deification belongs to a broader conception of the divine oikonomia: deification is the fulfillment of creation, not just the rectification of the Fall. One way of putting this is to think in terms of an arch stretching from creation to deification, representing what is and remains God's intention: the creation of the cosmos that, through humankind, is destined to share in the divine life, to be deified. Progress along this arch has been frustrated by humankind, in Adam, failing to work with God's purposes, leading to the Fall, which needs to be put right by redemption. There is, then, what one might think of as a lesser arch, leading from Fall to redemption, the purpose of which is to restore the function of the greater arch, from creation to deification. The loss of the notion of deification leads to lack of awareness of the greater arch from creation to deification, and thereby to concentration on the lower arch, from Fall to redemption; it is, I think, not unfair to suggest that such a concentration on the lesser arch at the expense of the greater arch has been characteristic of much Western theology. The consequences are evident: a loss of the sense of the cosmic dimension of theology, a tendency to see the created order as little more than a background for the great drama of redemption, with the result that the Incarnation is seen simply as a means of redemption, the putting right of the Fall of Adam: O certe necessarium Adae peccatum, quod Christi morte deletum est! O felix culpa, quae talem ac tantum meruit habere Redemptorem!--as the [Exultet of the Easter Vigil] has it: "O certainly necessary sin of Adam, which Christ has destroyed by death! O happy fault, which deserved to have such and so great a Redeemer!"

Orthodox theology has never lost sight of the greater arch, leading from creation to deification.

Inhabiting the Cruciform God: Kenosis, Justification, and Theosis in Paul’s Narrative Soteriology

Michael J. Gormanmy source: Denver Seminary

Oct 8, 2009Series: Volume 12 - 2009Michael J. Gorman. Inhabiting the Cruciform God: Kenosis, Justification, and Theosis in Paul’s Narrative Soteriology. Grand Rapids and Cambridge: Eerdmans, 2009. $24.00 pap. Xi + 194 pp. ISBN 978-0-8028-6265-5

While staunch defenders of the Reformation and equally outspoken proponents of the so-called new perspective on Paul garner much of the attention in Pauline studies these days, Michael Gorman, an evangelical professor of Sacred Scripture and dean of the Ecumenical Institute of Theology at St. Mary’s Seminary and University in Baltimore, is quietly making repeated, solid contributions to this debate that combine the best of old and new looks. Already his previous works, especially Apostle of the Crucified Lord: A Theological Introduction to Paul and His Letters (Eerdmans, 2004) and Cruciformity: Paul’s Narrative Spirituality of the Cross (Eerdmans, 2001), have demonstrated both his command of Paul and his ability to chart a sensible via media in the often polarized discussions of Paul’s thought.

Although Gorman’s latest book is not a large one, it is tightly packed with rich and rewarding treatments of the interconnectedness of key themes in Pauline soteriology. Gorman’s four main chapters make his case in four discrete stages. First, Philippians 2:6-11 shows that Christ’s self-emptying or kenosis reveals the character of God. Believers do not merely imitate Jesus in this self-giving but actually participate in it via their co-crucifixion with Christ and their co-resurrection with him to perfect humanity, partially realized in the present and fully in the life to come. Because this Christlikeness is also Godlikeness, and because we actually participate with Christ in this process, the concept of theosis (deification or divinization) may properly be applied to the Christian’s experience at this juncture.

Second, Galatians 2:15-21 and Romans 6:1-7:6 demonstrate “that justification is by co-crucifixion; it is participation in the covenantal and cruciform narrative identity of Christ, which is in turn the character of God; thus justification is itself theosis” (p. 2). Gorman clearly eschews any criticism of substitutionary atonement, fashionable in various branches of Pauline studies today. He simply stresses the need to encapsulate this heart of the Reformers’ emphasis in the broader frameworks in which Paul places it: justification is both forensic and participatory. Thus Galatians 2:20 makes it clear that justification is not merely the legal declaration of a sinner’s acquittal because of Christ’s imputed righteousness, but the actual death of the believer to living by the Law. Justification and sanctification, therefore, begin to merge. Through the Spirit, justified believers are of necessity morally transformed, to some degree, over time, already in this life (see esp. Rom. 6:1-6). Indeed, “in Pauline theological forensics, God’s declaration of ‘justified!’ now is a ‘performative utterance,’ an effective word that does not return void but effects transformation” (p. 101). This transformation changes our relationships with both God and believers. The double love command sums up the ethics of Paul just as much as it does explicitly for those of Jesus (Mark 12:28-33 pars.), even if it never appears in that form in so many words in the writings of the apostle to the Gentiles. And enacting divine love can never be separated from pursuing his justice, so no one need fear that this focus on love works against the struggle for justice in our world.

Third, Paul the Jew knows well God’s call to be holy as he is holy (Lev. 19:1). To be holy, therefore, is to be Godlike. But Paul stresses our recreation in the image of God, just as Christ is the perfect image of God, in righteousness and holiness (cf. Col. 3:10 and Eph. 4:24), through the power of the Spirit (see esp. 2 Cor. 3:7-4:6). As we are increasingly conformed to Christ’s moral likeness, then, our justification becomes our theosis. Little wonder, then, that Paul regularly calls us “saints” (“holy ones”) or that sanctification is a central theme particularly in 1 Thessalonians, Galatians, 1 and 2 Corinthians, and Philippians. Nor is this merely individual growth in being like God, it is also corporate as the church becomes what it was called to be.

Finally, moving to what is conventionally distinguished as the ethical realm but which Gorman’s study argues cannot really be so separated, co-crucifixion with Christ (which equals justification, which equals holiness and therefore sanctification as well, and which equals theosis), means a commitment to non-violent living. We may as believers have to absorb violence as both Jesus and Paul did. We may stand for things with great ardor as both men did. But Paul’s murderous, Phineas-like zeal , which was transformed when he became a Christian into passionate but cruciform living, should play no role in the believer’s life. We may at times have to exclude others who will not respond to church discipline (1 Cor. 5:1-5) but it dare not involve violence. And precisely because God has guaranteed his perfectly holy wrath to be poured out on Judgment Day on those outside his community of saints who finally refuse his loving overtures, we do not have to take vengeance into our own hands.

There are a number of places where important questions remain for Gorman’s views. Given the ease with which Western readers unfamiliar with all of the historic nuances of “theosis” can assume it means becoming godlike in ways that would compromise his sovereignty and lordship, it is not at all clear how “not to use such a word “would mean seriously misrepresenting what is at the core of Paul’s theology” (p. 8). Key theological terms can always be explained in other words when the terms themselves may mislead. Gorman’s notion that “being (in the form of God)” is a causal rather than (or in addition to) a concessive participle in Philippians 2:6 seems unlikely. Romans 5:1-11 rather clearly presents reconciliation as a key result of justification, not as synonymous with it. The view that pistis Christou is a subjective genitive (“the faithfulness of Christ”), though currently fashionable, is grammatically tortuous, and Gorman’s case doesn’t depend on it anyway. Unless Gorman wishes to obliterate every distinction between believers’ theosis and Christ’s role in the Godhead, it is not enough to point to our co-crucifixion with Christ to solve the thorny debates that swirl around pacifism. What may have been necessary to atone for the sins of the world, which we cannot emulate or replicate, may not be the path to which the believer is called in every conceivable context. Romans 1:17 and 18 pair the revelation of God’s righteousness and his wrath in the framework of the New Testament’s famous “already but not yet” timetable. If believers participate, in part in the present, in the revelation of God’s righteousness they may well at times have to participate in his wrath. But Gorman’s excess, if it is that, is still far preferable to our all-too-common trigger-happy American civil religion! Many evangelicals quote Romans 13:1-7 far too glibly and without exegetical sophistication; still it is striking that Gorman does not treat it at all in his chapter on non-violence (and only once in passing elsewhere).

It would be a pity if any or all of these caveats would ward anyone off from wrestling in detail with Gorman’s proposals and from appreciating the many strengths of his main points in each chapter. It may well be that this particular combination of emphases and the language used to unpack them serves Gorman best in the context of an ecumenical institute in a largely Roman Catholic context . Other contexts may require slightly different emphases and terminology. But whenever believers of any stripe lose sight of and stray from the fundamentally cruciform lifestyle that is at the heart of true Christian practice, precisely because it is at the heart of the divine behavior disclosed in Jesus, they stray from genuine Christianity.

Craig Blomberg, Ph.D.

Distinguished Professor of New Testament

Denver Seminary

October 2009

Pope Francis, Romans 8, and the theme of theosis

"All who are led by the Spirit of God are sons of God..."

May 08, 2013 06:23 ESTCarl E. Olson

Pope Francis made some waves today when he spoke to the plenary assembly of the International Union of Superiors General (UISG) about "men and women of the Church who are careerists and social climbers, who 'use' people, the Church, their brothers and sisters—whom they should be serving—as a springboard for their own personal interests and ambitions." It was another example of how the Holy Father—pick a cliché—pulls no punches and wastes no words.

We'll have more about that particular address and related matters soon, but I want to reflect a moment on Francis's general audience today, which focused on the work of the Holy Spirit, the gift of divine life, and the mystery of divine sonship. These are topics and themes that he has touched on several times already in the first weeks of his pontificate. A month ago, in his April 10th general audience, Francis asked, "What does the Resurrection mean for our life?" His answer, in part, is that the Resurrection (as the Apostle Paul explained) is not just freedom from, but freedom for: "we are set free from the slavery of sin and become children of God; that is, we are born to new life." This freedom is received in and through the sacrament of Baptism. Having received the sacrament, the baptized person emerged from the basin and put on a new robe, the white one; in other words, by immersing himself in the death and Resurrection of Christ he was born to new life. He had become a son of God. In his Letter to the Romans St Paul wrote: “you have received the spirit of sonship. When we cry ‘Abba! Father! it is the Spirit himself bearing witness with our spirit that we are children of God” (Rom 8:15-16).

It is the Spirit himself whom we received in Baptism who teaches us, who spurs us to say to God: “Father” or, rather, “Abba!”, which means “papa” or [“dad”]. Our God is like this: he is a dad to us. The Holy Spirit creates within us this new condition as children of God. And this is the greatest gift we have received from the Paschal Mystery of Jesus. Moreover God treats us as children, he understands us, he forgives us, he embraces us, he loves us even when we err. In the Old Testament, the Prophet Isaiah was already affirming that even if a mother could forget her child, God never forgets us at any moment (cf. 49:15). And this is beautiful!

This gift of supernatural filiation goes by many names, including divinization, deification, and theosis, as it is widely known in the Eastern Catholic and Orthodox churches. It is a teaching that has long interested me. It was a key reason for becoming Catholic many years ago, and it is the focus of a book I am co-editing with Fr. David Meconi, SJ, editor of Homiletic & Pastoral Review and assistant professor of theological studies at Saint Louis University, whose doctoral dissertation was on St. Augustine’s use of deification. The book has fifteen chapters by fourteen contributors (as well as a Foreword by Dr. Scott Hahn) and it covers two thousand years of Catholic teaching on the topic of theosis, beginning with Scripture and concluding with the Catechism of the Catholic Church and recent papal documents. This week, I am finishing up the final section of the opening chapter, co-authored with Fr. Meconi, on theosis in Sacred Scripture.

And so today's audience by Francis caught my attention, as he returns to the same themes as he highlighted a month ago. For example:

But I would like to focus on the fact that the Holy Spirit is the inexhaustible source of God's life in us. In all times and in all places man has yearned for a full and beautiful life, a just and good one, a life that is not threatened by death, but that can mature and grow to its fullest. Man is like a traveler who, crossing the deserts of life, has a thirst for living water, gushing and fresh, capable of quenching his deep desire for light, love, beauty and peace. We all feel this desire! And Jesus gives us this living water: it is the Holy Spirit, who proceeds from the Father and who Jesus pours into our hearts. Jesus tells us that "I came that they may have life and have it more abundantly" (John 10, 10).

The Holy Father touches on a couple of passages in the Fourth Gospel, which is rich with the theme of mankind being called to share in God's divine life; the same can be said of 1 John. Speaking of the "living water" spoken of by Jesus to the Samaritan woman by the well, Francis remarks:

The '"living water," the Holy Spirit, the Gift of the Risen One who comes to dwell in us, cleanses us, enlightens us, renews us, transforms us because rendering us partakers of the very life of God who is Love. This is why the Apostle Paul says that the Christian's life is animated by the Spirit and by its fruits, which are "love, joy, peace, generosity, kindness, goodness, faithfulness, gentleness, self-control" (Gal 5:22 -23). The Holy Spirit leads us to divine life as "children of the Only Son." In another passage from the Letter to the Romans, which we have mentioned several times, St. Paul sums it up in these words: "All who are led by the Spirit of God are sons of God. And you… have you received the Spirit who renders us adoptive children, and thanks to whom we cry out, "Abba! Father. “The Spirit itself, together with our own spirit, attests that we are children of God. And if we are His children, we are also His heirs, heirs of God and fellow heirs with Christ, provided we take part in his suffering so we can participate in his glory "(8, 14-17). This is the precious gift that the Holy Spirit brings into our hearts: the very life of God, the life of true children, a relationship of familiarity, freedom and trust in the love and mercy of God, which as an effect has also a new vision of others, near and far, seen always as brothers and sisters in Jesus to be respected and loved.

It is readily evident that Romans 8:15-17 is a passage with great significance for Francis, as he himself notes that he has mentioned it "several times." He does not, of course, use the term "theosis", but explicates the doctrine using language that is largely keeping with the Western way of referring to it. In fact, a quick search of the Vatican site turns up just a few uses of it among the documents accessible there, two of which are notable. First, Pope Benedict XVI made mention of it in a 2009 audience about John Scotus, and in the 2011, document, “Theology Today: Perspectives, Principles, and Criteria”, the International Theological Commission articulated a succinct and helpful definition:

The Mystery of God revealed in Jesus Christ by the power of the Holy Spirit is a mystery of ekstasis, love, communion and mutual indwelling among the three divine persons; a mystery of kenosis, the relinquishing of the form of God by Jesus in his incarnation, so as to take the form of a slave (cf. Phil 2:5-11); and a mystery of theosis, human beings are called to participate in the life of God and to share in ‘the divine nature’ (2 Pet 1:4) through Christ, in the Spirit. (par 98)

The term "divinization" appears over thirty times in English texts on the site; it was used often by Bl. John Paul II, for whom the theme was of great importance, as I've shown elsewhere. Especially interesting is how Benedict XVI emphasized the connection between divinization, conversion, and spiritual growth, both individual and communal. In the October 2010 homily at the papal Mass for the opening of the special assembly for the Middle East, Benedict stated:

Without communion there can be no witness: the life of communion is truly the great witness. Jesus said it clearly: "It is by your love for one another, that everyone will recognize you as my disciples" (Jn 13: 35). This communion is the life of God itself which is communicated in the Holy Spirit, through Jesus Christ. It is thus a gift, not something which we ourselves must build through our own efforts. And it is precisely because of this that it calls upon our freedom and waits for our response: communion always requires conversion, just as a gift is better if it is welcomed and utilized.

Benedict pointed back to this remark in the opening paragraphs of of his September 2012 Post-Synodal Apostolic Exhortation, Ecclesia in Medio Oriente, writing:

In the context of the Christian faith, “communion is the very life of God which is communicated in the Holy Spirit, through Jesus Christ”. It is a gift of God which brings our freedom into play and calls for our response. It is precisely because it is divine in origin that communion has a universal extension. While it clearly engages Christians by virtue of their shared apostolic faith, it remains no less open to our Jewish and Muslim brothers and sisters, and to all those ordered in various ways to the People of God. The Catholic Church in the Middle East is aware that she will not be able fully to manifest this communion at the ecumenical and interreligious level unless she has first revived it in herself, within each of her Churches and among all her members: Patriarchs, Bishops, priests, religious, consecrated persons and lay persons. Growth by individuals in the life of faith and spiritual renewal within the Catholic Church will lead to the fullness of the life of grace and theosis (divinization). In this way, the Church’s witness will become all the more convincing. (par 3)

In other words, if I might try to summarize, we must grow in divine life so that the Church can be renewed, so we might better proclaim the Gospel, and we might give better witness to the Catholic Faith, the heart of which is the supernatural sonship granted in baptism, by the power of the Holy Spirit. This is already a focus of the pontificate of Francis, and it seems to me that one reason is that he wants to emphasize that real, substantial renewal comes from becoming—as John Paul II liked to say—what we are: children of God. And in this way, both are reiterating what the Apostle John wrote nearly two thousand years ago: "See what love the Father has given us, that we should be called children of God; and so we are" (1 Jn 3:1).

35

About the Author

Carl E. Olson editor@catholicworldreport.com

Carl E. Olson is editor of Catholic World Report and Ignatius Insight. He is the author of Did Jesus Really Rise from the Dead?, Will Catholics Be "Left Behind", co-editor/contributor to Called To Be the Children of God, co-author of The Da Vinci Hoax (Ignatius), and author of the "Catholicism" and "Priest Prophet King" Study Guides for Word on Fire. He is also a contributor to "Our Sunday Visitor" newspaper, "The Catholic Answer" magazine, "Chronicles", and other publications.

No comments:

Post a Comment