This post consists of two articles, one on the Cross by St Maria Skobtsova and the other about St Teresa Benedicta of the Cross and her relationship with the Cross. One saint is Orthodox and the other Catholic. Both were nuns and both died at the hands of the Nazis during the 2nd World War. Both showed a forgetfulness of self and an overflowing love for others in the time they were in their respective concentration camps, as you would expect from saints so devoted tp the Cross and Resurrection. They speak different devotional language, but both messages had in common a strong sense of the Church (sobornost) in relation to Christ's sufferings and their own. They are living proof (or perhaps dying proof) that our divisions do not extend to heaven.

TAKING UP THE CROSS

OCTOBER 27, 2007 ADMININCOM

by St. Maria Skobtsova

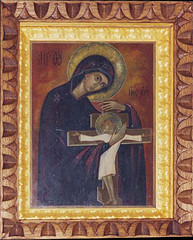

Cross-bearing Theotokos painted by St. Maria Skobtsova of Paris

We must seek authentic and profound religious bases in order to understand and justify our yearning for man, our love of man, our path among our brothers, among people.

And warnings sound from two different sides. On one side, the humanistic world, even as it accepts the foundations of Christian morality in inter-human relations, simply does not need any further deepening, any justification that does not come from itself. This world keeps within three dimensions, and with those three dimensions it exhausts the whole of existence. On the other side, the world connected with the Church also warns us: often the very theme of man seems something secondary to it, something that removes us from the one primary thing, from an authentic communion with God. For this world, Christianity is this relation to God. The rest is christianizing or christianification.

We must be deaf to these two warnings. We must not only suppose, we must know that the first of them, coming from a world deprived of God, destroys the very idea of man, who is nothing if he is not the image of God, while the second destroys the idea of the Church, which is nothing if it does not imply the individual human being within it, as well as the whole of mankind.

We must not only be deaf to these warnings, we must be convinced that the question of an authentic and profound religious attitude toward man is precisely the meeting point of all questions of the Christian and the godless world, and that even this godless world is waiting for a word from Christianity, the only word capable of healing and restoring all, and perhaps sometimes even of raising what is dead.

But at the same time, perhaps for centuries now, the Christian soul has been suffering from a sort of mystical Protestantism. Only the combination of two words carries full weight for it: God and I, God and my soul, and my path, and my salvation. For the modern Christian soul it is easier and more natural to say “My Father” than “Our Father,” “deliver me from the evil one,” “give me this day my daily bread,” and so on.

And on these paths of the solitary soul striving toward God, it seems that everything has been gone through, all roads have been measured, all possible dangers have been accounted for, the depths of all abysses are known. It is easy to find a guide here, be it the ancient authors of ascetic books, or the modern followers of ancient ascetic traditions, who are imbued with their teachings.

But there is also a path that seeks a genuinely religious relation to people, that does not want either a humanistic simplification of human relations or an ascetic disdain of them.

Before speaking of this path, we must understand what that part of man’s religious life which is exhausted by the words “God and my soul” is based on in its mystical depths.

If we decide responsibly and seriously to make the Gospel truth the standard for our human souls, we will have no doubts about how to act in any particular case of our lives: we should renounce everything we have, take up our cross, and follow Him. The only thing Christ leaves us is the path that leads after Him, and the cross which we bear on our shoulders, imitating His bearing of the cross to Golgotha.

It can be generally affirmed that Christ calls us to imitate Him. That is the exhaustive meaning of all Christian morality. And however differently various peoples in various ages understand the meaning of this imitation, all ascetic teachings in Christianity finally boil down to it. Desert dwellers imitate Christ’s forty-day sojourn in the desert. Fasters fast because He fasted. Following His example, the prayerful pray, virgins observe purity, and so on. It is not by chance that Thomas Kempis entitled his book The Imitation of Christ; it is a universal precept of Christian morality, the common title, as it were, of all Christian asceticism.

I will not try to characterize here the different directions this imitation has taken, and its occasional deviations, perhaps, from what determines the path of the Son of Man in the Gospel. There are as many different interpretations as there are people, and deviations are inevitable, because the human soul is sick with sin and deathly weakness.

What matters is something else. What matters is that in all these various paths Christ Himself made legitimate this solitary standing of the human soul before God, this rejection of all the rest – that is, of the whole world: father and mother, as the Gospel precisely puts it, and not only the living who are close to us, but also the recently dead – everything, in short. Naked, solitary, freed of everything, the soul sees only His image before it, takes the cross on its shoulders, following His example, and goes after him to accept its own dawnless night of Gethsemane, its own terrible Golgotha, and through it to bear its faith in the Resurrection into the undeclining joy of Easter.

Here it indeed seems that everything is exhausted by the words “God and my soul.” All the rest is what He called me to renounce, and so there is nothing else: God – and my soul – and nothing.

No, not quite nothing. The human soul does not stand empty-handed before God. The fullness is this: God – and my soul – and the cross that it takes up. There is also the cross.

The meaning and significance of the cross are inexhaustible. The cross of Christ is the eternal tree of life, the invincible force, the union of heaven and earth, the instrument of a shameful death. But what is the cross in our path of the imitation of Christ; how should our crosses resemble the one cross of the Son of Man? For even on Golgotha there stood not one but three crosses: the cross of the God-man and the crosses of the two thieves. Are these two crosses not symbols, as it were, of all human crosses, and does it not depend on us which one we choose? For us the way of the cross is unavoidable in any case, we can only choose to freely follow either the way of the blaspheming thief and perish, or the way of the one who called upon Christ and be with Him today in paradise. For a certain length of time, the thief who chose perdition shared the destiny of the Son of Man. He was condemned and nailed to a cross in the same way; he suffered torment in the same way. But that does not mean that his cross was the imitation of Christ’s cross, that his path led him in the footsteps of Christ.

What is most essential, most determining in the image of the cross is the necessity of freely and voluntarily accepting it and taking it up. Christ freely, voluntarily took upon Himself the sins of the world, and raised them up on the cross, and thereby redeemed them and defeated hell and death. To accept the endeavor and the responsibility voluntarily, to freely crucify your sins – that is the meaning of the cross, when we speak of bearing it on our human paths. Freedom is the inseparable sister of responsibility. The cross is this freely accepted responsibility, clear-sighted and sober.

In taking the cross on his shoulders, man renounces everything – and that means that he ceases to be part of this whole natural world. He ceases to submit to its natural laws, which free the human soul from responsibility. Natural laws not only free one from responsibility, they also deprive one of freedom. Indeed, what sort of responsibility is it, if I act as the invincible laws of my nature dictate, and where is the freedom, if I am entirely under the law?

And so the Son of Man showed his brothers in the flesh a supra-natural – and in this sense not a human but a God-manly – path of freedom and responsibility. He told them that the image of God in them also makes them into God-men and calls them to be deified, to indeed become Sons of God, freely and responsibly taking their crosses on their shoulders.

The free path to Golgotha – that is the true imitation of Christ.

This would seem to exhaust all the possibilities of the Christian soul, and thus the formula “God and my soul” indeed embraces the whole world. All the rest that was renounced on the way appears only as a sort of obstacle adding weight to my cross. And heavy as it may be, whatever human sufferings it may place on my shoulders, it is all the same my cross, which determines my personal way to God, my personal following in the footsteps of Christ. My illness, my grief, my loss of dear ones, my relations to people, to my vocation, to my work – these are details of my path, not ends in themselves, but a sort of grindstone on which my soul is sharpened, certain – perhaps sometimes burdensome – exercises for my soul, the particularities of my personal path.

If that is so, it certainly settles the question. It can only be endlessly varied, depending on the individual particularities of epochs, cultures, and separate persons. But essentially everything is clear. God and my soul, bearing its cross. In this an enormous spiritual freedom, activity, and responsibility are confirmed. And that is all.

I think it is Protestant mysticism that should follow such a path most consistently. Moreover, in so far as the world now lives the mystical life, it is for the most part infected by this isolating and individualistic Protestant mysticism. In it there is, of course, no place for the Church, for the principle of sobornost’, for the God-manly perception of the whole Christian process. There are simply millions of people born into the world, some of whom hear Christ’s call to renounce everything, take up their cross, and follow Him, and, as far as their strength, their faith, their personal endeavor allow, they answer that call. They are saved by it, they meet Christ, as if merging their life with His. All the rest is a sort of humanistic afterthought, a sort of adjusting of these basic Christian principles to those areas of life that lie outside them. In short, some sort of christianification, not bad in essence, but deprived of all true mystical roots, and therefore not inevitably necessary.

The cross of Golgotha is the cross of the Son of Man, the crosses of the thieves and our personal crosses are precisely personal, and as an immense forest of these personal crosses we are moving along the paths to the Kingdom of Heaven. And that is all.

Mother Maria Skobtsova died on Good Friday, 1945, in Ravensbr ck concentration camp near Berlin. The “crime” of this Orthodox nun and Russian refugee was her effort to rescue Jews and others being pursued by the Nazis in her adopted city, Paris, where in 1932 she had founded a house of hospitality. On the 16th of January 2004, the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul resolved that Mother Maria and three of her collaborators, Fr. Dimitri Kl pinin, Yuri Skobtsova, and Elie Fondaminskii should be added to the church calendar. On the 1st and 2nd of May 2004, there were services at the Cathedral of Alexander Nevsky in Paris to celebrate the newly recognized saints. The essay reprinted here is part of a longer text included in Mother Maria Skobtsova: Essential Writings, translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky and published by Orbis Books.

From the Fall 2007 issue of In Communion / IC 47

Saint Edith Stein and the Meaning of the Cross

by Freda Mary Oben

A Jewish friend who had seemed to be quite ecumenical-minded surprised me one day by saying, “You know, for most Jews, the cross does not mean Christ. Turn the beams about and you have a swastika. Jews relate the cross not only to the Holocaust but to all the persecution down through the centuries -- the crusades, ghettos, pogroms, expulsions from native homelands, forced conversions -- you name it!”

Edith Stein was born Jewish. What did the cross mean to her?

She was born in Germany in 1891, on the most holy Jewish day of the year, the Day of Atonement, which fell in that year on October twelfth. The Jewish community, after a twenty-four hour fast, listens in delight to the blowing of the Shofar -- a beautiful sound from the horn. This end of their sacred liturgy not only signals that they can eat but announces a new birth into life and freedom from sin.

It is easily understood that Edith’s own passion for the cross is a flowering of the seeds first planted by the Jewish faith in redemption. Yet, through her conversion in 1922 and martyrdom just twenty years later, she becomes a sign of both faiths. She is that “new person born through Christ’s reconciliation of Jew and Gentile on the cross” (Eph 2:14-16). And she becomes thereby a symbol of the sacred link between the two faiths.

Edith had experienced personally what redemption means when she accepted the Catholic faith. She had been an atheist from the age of fourteen to twenty-one years, and she always remembered somewhat sadly her “radical sins of disbelief”. She writes that the person turned away from God can refuse to turn back to Him even if touched by Him. But, if in hearing God’s word, the person accepts the faith, then God sees the penitent in Christ and accepts Christ’s expiation for his/her sins. The convert is justified in Christ and through baptism becomes a member of the Mystical Body of Christ.

Immediately after her own conversion, Edith had wanted to become a religious. However, her spiritual director counseled her not to do this: her mother was suffering deeply from Edith’s conversion and Edith had an important role to play as a laywoman in both philosophy and education.

Response to Anti-Semitism

By 1930, Hitler was outspoken in his flagrant anti-Semitism. Edith’s response can be found in a letter of that time: her only answer to conditions that she was otherwise powerless to change is her urgent cry to enact an inner holocaustum. But three years later when Hitler became the Reichchancellor, she wrote another letter, one that has been widely recognized and acclaimed. The first economic boycott against the Jews had just taken place in April. Was it Edith’s intellectual and spiritual genius that urged her to write to Pope Pius XI, pleading with him to issue an encyclical condemning the Jewish persecution? She prophesied that what would happen to Jews would eventually happen to Catholics as well.

After writing this letter, she traveled to the Benedictine abbey in Beuron for the week of Easter, as was her habit each year. On the way she stopped at the Carmel in Cologne for the holy hour on the eve of the first Friday. She tells us in an essay “The Road to Carmel”,

I talked with the Savior and told Him that I knew that it was His Cross that was now being placed upon the Jewish people; that most of them did not understand this; but that those who did, would have to take it up willingly in the name of all. I would do that. He should only show me how. At the end of the service, I was certain that I had been heard. But what this carrying of the cross was to consist in, that I did not yet know. (Posselt, Edith Stein 116)

She was at that time a professor at the German Scientific Institute of Pedagogy in Muenster. Her last lecture before this Easter holiday had been on February 25. When she returned, her teaching post had been canceled. The Institute was Catholic, but, as all educational sites, under state control. After all, she was born Jewish. Now, as for all German Jews, the crisis in her life severely escalated. Looking back at that time, she assures a friend, “for those who love Him, God turns everything to the good”. Yet she also confesses, “Never have I prayed the Divine Office of the Martyrs, which recurs so frequently during the Easter cycle, with greater fervor than I did at that time” (Stein, Self-Portrait 223).

Now in 1933, she wondered if, after almost twelve years since her baptism, she might not be free to enter the religious life. On the thirtieth of April, she went to pray at St. Ludgeri Church in Muenster, which was observing thirteen consecutive hours of devotion to the Good Shepherd. She promised herself not to leave the church until she had made a decision. She writes, “After the final blessing had been pronounced, I had the assurance of the Good Shepherd” (Posselt 118).

She knew that she had to help carry the cross being laid on the Jews and that she had to share in their destiny. She knew that she had to spend her life in the prayer of expiation for the sins being shed and for the safety of the humanity she so loved. Carmel was the place for her. Of course, it had been a reading of the autobiography of Teresa of Avila, founder of the Carmelite order, which had finally carried her into the Church. But for Edith, Carmel excels as an order because of its unique identification with the Crucified Christ.

She explains this clearly. All persons are united in the Mystical Body of Christ. His suffering continues in us because Christ is in His members; thus we are enabled to share in His redemptive action. This is true in all religious life, but it is especially true of the Carmelite who stands as proxy for the salvation of sinners, freely and joyfully.

She writes that Carmelite prayer wins grace for souls. Only a participation in Christ’s Passion can help to save humanity, and she desires a share in that. She describes prayer as the highest human action, “the highest achievement of which the human spirit is capable” (Stein, The Hidden Life 38).

Edith Stein has written beautiful essays defining Carmelite spirituality. In one, “The Marriage of the Lamb” (Stein, The Hidden Life 99), we find:

The spouse whom she [the Carmelite] chooses is the Lamb that was slain. If she is to enter into heavenly glory with Him she must allow herself to be fastened to His cross. The three vows are the nails. The more willingly she stretches herself out on the cross and endures the blows of the hammer, the more deeply will she experience the reality of her union with the Crucified. Then being crucified itself becomes for her the marriage feast.

A Jesuit priest has witnessed that three weeks before her death, “She spoke about the vocation of a Carmelite, how she must represent love in a world of hate” (Herbstrith, Edith Stein 128).

How was her Jewish family responding to all this? Of course, their pain was a great part of her anguish. Her conversion had been difficult enough for them, but her entry into Carmel in 1933, at the very time when their fate as a people was so threatened, seemed to be absolute betrayal. Edith tried to explain to them that she would always be part of the family and of the Jewish people and that being behind cloistered walls would not protect her. Their inability to accept this constituted her cross.

And it was through the Crucified Christ that she found the necessary strength to endure this anguish. She writes in a poem, “Das Wort vom Kreuz” (“Word from the Cross”) that God strengthens what seems to the world like foolishness. This is her hope, the hope of her life. Her impassioned poetry expresses the inner holocaustum for which she had prayed. In “Jesus von Nazareth”, she exults in Christ’s deep humanity and love; He holds the answer to the riddle of her being and to the question of suffering. She asks, “Christ, who suffers for me in this world? Who died for me freely out of Love? I know of no one but Jesus the Crucified and Resurrected” (Herbstrith, Beten Mit Edith Stein 25, 27).

Sacrifice Necessary to Overcome Evil

Edith writes of evil as a created spirit who chooses to behave perversely, a spirit who can only be counteracted by God’s spirit of love. She was, after all, suffering as a German and a Christian as well as a Jew. Toward the end of her life she said to a priest, “Who is expiating for what is happening to the Jewish people because of the German people? Who is turning this horrible guilt to a blessing for both peoples?” (Herbstrith, Edith Stein 134). In a letter of 1938, she writes:

I also trust in the Lord’s having accepted my life for all of them. I keep having to think of Queen Esther who was taken from among her people precisely that she might represent them before the King. I am a very poor and powerless little Esther, but the King who chose me is infinitely great and merciful. That is such a great comfort (Stein, Self-Portrait 291).

But we know that her suffering was also great. By 1938, many of her family had emigrated, and she feared for those remaining in Germany. However, her prayers were for all humanity: that Germany would be delivered from the Anti-Christ -- Hitler -- and that the world would find peace. As a Red Cross nurse during World War I, she had learned the misery of war, the bitter torment of both soldiers and civilians. Now, from visitors at the grill of the Echt Carmel to which she had been transferred for safety, she heard enough to realize some of the horror then happening. In poetic prayer, “To God, the Father”, she writes of deeply troubled and lonely souls:

Bless all the hearts, the clouded ones, Lord, above all,Bring healing to the sick.To those in torture, peace.Teach those who had to carry their beloved to the grave, to forget.Leave none in agony of guilt on all the earth.(Batzdorff, Edith Stein Selected Writings 81)

But, she tells us in the essay “The Mystery of the Cross” that Christ came because of sin and evil: “The mystery of the Incarnation is closely linked to the mystery of iniquity” (Graef, Writings of Edith Stein 22). The crib is surrounded by martyrs, for Christ’s way is “from the crib to the cross”. We are asked to follow Him, to become His allies in His fight against evil. Voluntary suffering in expiation of human sins unites us to the Lord. To such prayerful souls Christ gives His spirit and life, His power, meaning and guidance. For it is in His redemptive action that we participate; (Stein, The Hidden Life 91). “The entire sum of human failures from the first Fall up to the Day of Judgment must be blotted out by a corresponding measure of expiation” the cross is “that sign which stands upright for all eternity as the only way to heaven” (Batzdorff, An Edith Stein Daybook 33). By expiatory prayer, we win citizenry in heaven for others as well as for ourselves.

Intercession for Others in the Mystical Body

Edith Stein terms this prayer of expiation as Stellvertretung, i.e., acting as proxy. This means praying for pardon of another person’s sins: first, that God will permit the grace of contrition to the sinner; second, that we can immolate for the other’s sin, even bear the punishment due in justice to the other. We can do so even for our enemies, for God gives us the strength to do so. “The Being of God, the life of God, the essence of God, these are all love” (Stein, Thoughts 5). And, “The darker it gets around us here, the more we must open our hearts to the light from above” (Batzdorff, Daybook 31).

To understand Christ and to be united to Him, the soul must experience an inner crucifixion. To win this union, the soul must undergo death. Each person finds this inner union with Christ only by living a deep interior life, for it is in the soul’s inmost depths that one can surrender freely to this union. Our saint writes that such surrender is the highest form of freedom itself. God respects the soul’s freedom because He wants to be Lord of the soul through this free gift of love. And, by giving self totally to God for love of neighbor, in imitation of Christ Crucified, the person relives the Trinitarian life of mutual surrender. Thus, by a penitential spirit, we are united to God and to others in God.

We can understand the history of salvation only by viewing humanity as one unique, great individual in the process of growth starting and ending in Christ. For, “He created man in His image, an image which He had designed from the beginning, to realize it eventually in His own person.” Christ is “the total plenitude of humanity” and each of us is created to imitate this fullness. The effort of each individual and of the common efforts of the entire human family is needed to win the fullness of total humanity. Yet it is the grace that flows from Christ that enables us to do so. For He is the “head” of total creation and His grace flows into this creation, His body. We cannot find our way to God without Him.

Christ is also the “head” of the redeemed human race, for He atoned for the sins of all people and “the life of grace overflows from Him into all those who he redeemed”. Thus total humanity becomes the Mystical Body of Christ. She writes, “And it seems to me that it pertains to the meaning of the Mystical Body of Christ that there is nothing human -- sin excepted -- that does not pertain to the vital unity of this body.” (Stein, Finite and Eternal Being 520-27). Edith fervently believed that total revelation is found only in the Catholic Church; yet, she also could not believe that salvation itself depends on the outer limits of any one church. Her thought clearly preceded by many years the declaration of Vatican Council II, Nostra Aetate, on the relationship of the Church to non-Christian religions.

Edith Stein’s total offering of self is based on her reverence for each person as an image of God, for her offering embraces those of every religion, culture, and race. She had a natural, rich empathy with all persons. Her concept of human solidarity is in keeping with the Biblical account of humanity created as one family. She writes that we are conditioned to dislike or hate those different from ourselves. Much of her early work was political in nature, stressing the concept of humane community and the exercise of human rights.

Even her poetry carries this theme passionately. In “Der Naechste” (“Our Neighbor”), she exclaims: “But of our brother? -- the seedy, unformed person so utterly unlike us in heritage, upbringing, race, color of skin? Jesus, who could have thought that love for God could be so hard.” (Herbstrith, Beten 23).

Edith offers herself for God’s glory in her will, written in 1939. A misunderstanding of the wording in this document has caused much tension in the Jewish community. It is important to note that the will is directed to Der Herr (God) and not to Der Herr Jesu (Jesus), and Edith always stressed the importance of precise wording. In her will, she prays for the peace of the world, for the deliverance of Germany, for the Church and its orders, for the honoring of the Immaculate Heart of Mary and the Sacred Heart of Christ, for the safety of her own family, and that all Jewish people will turn from disbelief to belief in God.

Before Hitler’s rise to power, many Jews in Germany had become “assimilated” and even agnostic. Members of Edith’s family were so. And she always remembered sadly her own period of atheism, “her radical sin of disbelief”. Perhaps she was thinking in her will that God was calling His Chosen People back to Him, as did many of the Jews themselves.

Edith’s prayer was answered on all counts. She died for both her Jewish people and for the Church. First, she was arrested through a direct response of the Nazi authorities to a pastoral letter read from all Catholic pulpits in Holland on July 26, 1942. The bishops were protesting the deportation of the Jews and the forced exclusion of baptized Jewish children from Catholic schools. Edith was arrested the following Sunday, August 2, along with all Jews baptized as Catholics. The chief Nazi authority, Dr. Seys-Inquaart, stated plainly in his newspaper on the following day that the National Socialists considered Jewish Catholics as their chief enemies to be removed from Holland as quickly as possible. This reprisal was a clear declaration of Fides odium -- hatred of the Church.

When she was picked up at the Echt Carmel with her sister Rosa, who had become a Catholic and was serving the Carmelites as portress, Edith said “Come, we will go for our people” (Stein,Briefauslese 136). Before her deportation to Auschwitz, she was given the opportunity to make a further appeal, but she answered that the purpose of her life would be lost if she did not share the destiny of her Jewish brethren. She died on August 9, shortly after their arrival at Auschwitz, as a Jew and as a Christian.

Witness to Truth: In His Footsteps

Edith’s pilgrimage induced her to place herself not only into the shoes of the oppressed, but, in the very shoes of Christ, to walk in His footsteps to the end. For, “The path of human destiny is a path from Christ to Christ” (Herbstrith, Beten 25). She writes that we are called to become “an other Christ” for He is the perfect shape of the human soul. He epitomizes the total fullness of humanity; thus, in following Him, the person becomes fully human. For Christ is the perfect image of God as person, “the archetype of all personality and the embodiment of all value” (Stein,Essays on Woman 259). In following Christ, one finds oneself.

Edith describes her own life in the sentence: “The finger of the Almighty writes the lives of His saints so that we read and praise His wondrous works.” Her trust in His providential plan was absolute. She once wrote that, if she could only say one thing, it would be to entreat that we live peacefully in the hand of the Lord.

She means so much to us in this third millennium of Christianity because of her authentic witness to the truth and power of Christ. She understood literally God’s mandate to be holy because He is holy, to love Him totally, and to love our neighbors in Him. She is an example for scholars and scientists, that they not be led by confidence in intellect alone but by trust in faith. She offers hope to the atheist who is searching for truth.

Our saint leads us as individuals to perfect contrition and conversion, to a fuller development of ourselves as persons, to a right vocation, and to a more bountiful self-giving of life and talents to the Church and to the world. She tells us that, to shape the world for the coming of God’s Kingdom, we are responsible for all others as well as for ourselves. She inspires us to work for peace, freedom, and human justice. As a symbol of all oppression, she encourages those who do suffer oppression and prejudice throughout the world because of race, religion, and nationality.

For her holiness of spirit points not only to the reconciliation between Jews and Christians, but to an end of all bigotry and oppression. As John Paul II said at Auschwitz in 1979, “Where are the boundaries of hate, the boundaries of persecution of human being through human beings, the boundaries of horror?”

Christ died to reconcile all mankind. In a sermon of Saint Leo the Great, we find:

One and the same Christ is present, not only in the firstborn of all creation, but in all His saints as well…. And so all that the Son of God did and taught for the world’s reconciliation is not for us simply a matter of past history. Here and now we experience His power at work among us…. But it is not only the martyrs who share in His passion by their glorious courage; the same is true, by faith, of all who are born again in baptism (Liturgy of the Hours II, 660-61).

Edith’s empowerment was her total faith in the Crucified Christ. This fullness of faith allowed her to write, with simplicity and exquisite beauty, that her greatest joy lay in hope of the vision to come.

Edith Stein, Teresa Benedicta of the Cross, was beatified in 1987, canonized in 1998, and named as co-patroness of Europe in 1999. We are encouraged to pray to her that she may help us on our journey through life and death to final resurrection.

Works cited

Batzdorff, Susanne M. Edith Stein Selected Writings. Springfield: Templegate, 1990.

… An Edith Stein Daybook. Springfield: Templegate, 1992.

Herbstrith, Waltraud. Beten Mit Edith Stein. Bergen-Enkheim bei Frankfurt/M: Kaffke, 1974.

… Edith Stein. Mainz: Topos, 1993.

Liturgy of the Hours. International Commission on English in the Liturgy. New York: Catholic Book Publishing Co, 1975.

Posselt, Teresia Renata de Spiritu Sancto, OCD. Edith Stein. Eds. Susanne M. Batzdorff, Josephine Koeppel, John Sullivan, Maria Amata Neyer. Washington, DC: Institute of Carmelite Studies, 2005.

Stein, Edith. Briefauslese 1917-1942. Freiburg: Herder, 1967.

… Essays on Woman. Trans. Freda Mary Oben. Washington, DC: Institute of Carmelite Studies, 1996.

... Finite and Eternal Being. Trans. Kurt F. Reinhardt. Washington, DC: Institute of Carmelite Studies, 2002.

… Self-Portrait in Letters 1916-1942. Trans. Josephine Koeppel, OCD. Washington, DC: Institute of Carmelite Studies, 1993.

… The Hidden Life. Trans. Waltraut Stein. Washington, DC: Institute of Carmelite Studies, 1992.

Freda Mary Oben, PhD, is a convert from Judaism, a lay Dominican (TOP), the mother of five and the grandmother of twelve. She received a doctorate from Catholic University of America in 1979, and taught at St. Joseph’s College, Howard University, and Washington Theological Union. Her four decades of research on Edith Stein has produced several published works, including a translation of Stein’s Essays on Woman (Institute of Carmelite Studies); Edith Stein – Scholar, Feminist, Saint (Alba House); The Life and Thought of St. Edith Stein (Alba House); and an album of tapes, Edith Stein A Saint for our Times (Institute of Carmelite Studies).

No comments:

Post a Comment