Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride for her husband. And I heard a voice from the throne saying, “See the home of God among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them; he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away.” And the one who was seated on the throne said, “See, I am making all things new.” (Rev, 21,1-5)

(An angel) (…) came and said to me, ‘Come and I will show you the bride , the wife of the Lamb. And in the Spirit he carried me away to a great, high mountain and showed me the holy city of Jerusalem coming out of heaven from God. It has the glory of God and a radiance like a very rare jewel, like jasper, clear as crystal. (…) And the wall of the city has twelve foundations, and on them are the twelve names of the twelve apostles of the Lamb. (…) I saw no temple in the city, for its temple is the Lord God, the Almighty, and the Lamb. The nations will walk by its light And the city has no need of sun or moon to shine on it, for the glory of God is its light, and its lamp is the Lamb. The nations will walk by its light, and the kings of the earth will bring their glory into it. (Rev. 21, 9ff)

Prophecy among the Jews was not so much about miraculously telling the future as interpreting the present from God’s point of view and telling people the future consequences of what is happening now. Apocalyptic literature often talked of present events as though they were foretold in the past. The Book of Revelation is different. It talks of present events as though they will happen in the future, as events of the eschaton, the last days. Christian eschatology has fundamentally changed the apocalyptic perspective. God’s plan for the end of the universe has already taken place in the resurrection of Christ and we Christians already participate in the ‘eschaton” by participating in the Christian Mystery: hence the Christian present reflects the future. What we have in this passage from the Book of Revelation is a teaching mainly about the Church contemporary with the author, but reflecting the end of the world.

The Apocalypse or Book of Revelation is part of the Bible, God’s Word for us, because the Church and its liturgy continues to anticipate the Last Day. The Church of the Apocalypse is where heaven and earth are joined. A main theme is the heavenly liturgy, centred on the throne and the Lamb. The Seer is taken up into heaven, while the Church on earth, the one founded on the Apostles, is seen as coming down from heaven. We are reminded of these words in the Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy.:

In the earthly liturgy, by way of a foretaste, we share in that heavenly liturgy which is celebrated in the holy city of Jerusalem toward which we journey together as pilgrims , and in which Christ is sitting at the right hand of God, a minister of the sanctuary and of the true tabernacle (cf. Apoc. 21, 2; Heb. 8,2)

However, to understand it we must know something about the temple in Jerusalem, what it meant to the Jews (and first generation Christians), and why it is used in apocalyptic descriptions of heaven. Its destruction in 70AD caused a major theological problem for the Jews (and Christians). Here we have a Christian answer to the problem of its destruction. God was present in the temple in a covenant relationship with the People of God, and he was approached by sacrifice, an act of the people in offering and of God in sanctifying, and thus giving concrete expression to that covenant. What happens to the covenant when there is no temple and hence no covenanted Presence, and no sacrifice to make the covenant relationship concrete? The destruction of the temple challenged the Church to go deeper into its understanding of Christ and find the answer there.

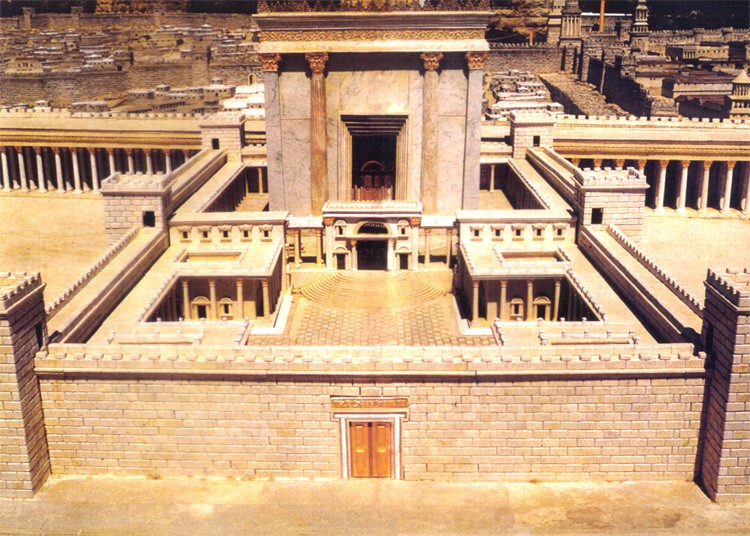

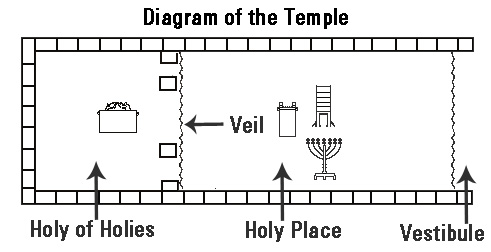

The temple was built on the Temple Mount. There were a number of concentric squares or courts: the higher they were, the holier they were. At the bottom was the great court open to Jews and gentiles alike, where there was a garrison of Roman soldiers. The rest was closed to all but the Jews. At the very top was the outer sanctuary (hekel) and, even a little higher, the Holy of Holies or debir where God’s presence was concentrated.

In ancient times the debir had contained the Ark of the Covenant with its two cherubim with touching wings on the lid and two very large cherubim, one on either side of the Ark. The whole complex formed God’s throne.

After the Assyrian invasion, the Ark and other ornaments were no longer there. Perhaps King Josiah took these objects out of the inner sanctuary, together with a bronze serpent and, possibly, other statues of cherubim, because he belonged to those (the Deuteronomists) who were completely opposed to any images and thought the Assyrian invasion had been a punishment from God for idolatry. Therefore in Christ’s time the Holy of Holies had no created thing inside, not even an altar.

The Ark of the Covenant vanished from history, but Ethiopians say that it is preserved in the town of Axum by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, far from the gaze of anyone who wishes to see it. A guardian is appointed for life. He enters the shrine area after the death of the last guardian, and doesn’t leave it until his own death.

Back in the temple, the living rock of the hill rose a little above the floor of the Holy of Holies, and it was on that rock that blood was sprinkled on the Day of Atonement.

Still in the sanctuary but outside the Holy of Holies, in what was called the hekel, was a gold altar where incense was offered morning and evening, and a gold covered table on which were the twelve loaves “of the Presence” or “of the Face” which were a kind of grain offering; and they were eaten by the priests each week after they had finished their week’s duty; though, originally, they were eaten only by the High Priest. New ones would be waiting on a marble table outside the sanctuary. Once the incoming priests had brought them into the sanctuary they became holy for being in God’s presence and were set before the Lord on the gold table and were sprinkled with frankincense. There was also the menorah or seven branched candlestick which represented the “tree of life” in the sanctuary. The furnishings of this part of the temple were made of gold.

The courtyard outside had furnishings of bronze. This included a huge tall altar upon which a fire normally burned. On each corner there was a horn of bronze. The ground sloped away from the altar and there were channels to take the blood which was poured at the foot of the altar, this constituting the sacrifice proper. Killing the animal was not a sacrifice – God is a God of life, not of death – so what was offered was the life of the animal which, the Jews believed, was contained in the blood. The animal was killed so that the priest could have its life to pour out before God. After being offered by being poured out at the base of the altar, the blood flowed down specially constructed channels and collected in a depository. When the sacrifices were over for the day, the whole area was sluiced with water, and the blood and water went out of the side of the temple by means of a canal, down into the Kedron Valley where the farmers bought it to enrich the soil. Often there was quite a lot of blood, especially at Passover. Josephus, the Jewish historian at the time of the destruction of Jerusalem in 70AD, calculated the number of lambs slaughtered in sacrifice on that day as two hundred and fifty five thousand, six hundred. They must have had an enormous amount of blood and water flowing from the side of the temple at the end of the day. According to St John, blood and water flowed from Christ’s side after his sacrifice: he had become the temple as well as the sacrifice.

The temple was where God lived among men: it was where heaven and earth were joined together and became one, which made possible the covenant relationship between God and the Jews. God’s presence in Jerusalem in his temple made that city the centre of the world, and it was by means of the temple that God blessed the whole human race. Although God is everywhere, it is only in the Jerusalem temple that God can be approached.

There were many kinds of sacrifice, but they had one thing in common: the Hebrew word for sacrifice, Qurban, comes from a verb that means “to approach” or “to draw near”. Sacrifice implies two activities, the human one of offering and the divine one of accepting, hence the establishment of or the confirming of a relationship. The relationship that specially concerned the Jews was the covenant between God and their race. The great question was, could the special relationship between God and the Jews exist without the temple and the ceasing of all sacrifice. Further, would God and the human race simply go their separate ways when the means of renewing that relationship was no longer there? Can anything be a substitute for the temple and its sacrifices?

There were the regular sacrifices, one in the morning and the other in the evening, and there were other sacrifices offered on behalf of particular people. There were also the major feast days. Passover involved an enormous slaughter of animals, as has already been remarked. They were killed in three sessions The skins went to the priests, as did a portion of each animal. The family or group, never less than ten in number, took the sacrificed sheep home where they were consumed in the paschal meal between sunset and midnight. This was to commemorate their flight from Egypt and their establishment as God’s people.

Another feast was the Day of Atonement, a day of penitence and cleansing. With the whole people fasting, the high priest, dressed in a white linen robe, would enter into the Holy of Holies and the divine Presence. He did this with great trepidation. He had a cord round his ankle so that, should God manifest himself and he were to die - " "You cannot see My face, for no one can see Me and live." (Exodus 33, 20),- his body could be pulled out; and there was another priest wearing the same robes who would then go into the Holy of Holies to finish the ceremony.

Firstly, two identical goats were chosen, one “for the Lord” and the other “for Azazel”, who may have been the prince of devils. Then a bull was slaughtered as a sin offering for the high priest’s sins and for the sins of all the other priests. He then went into the Holy of Holies and filled it with smoke from the incense, partly as an offering and partly, perhaps, as protection should God show himself in some way. “No one can see God and live.” He then went in with blood from the bull and sprinkled it on the mercy seat, which was at that time probably an outcrop of rock rising from the floor. Returning outside the Holy of Holies, the goat “for the Lord” was killed, and the high priest sprinkled his blood on the mercy seat. He also sprinkled blood on the horns of the golden altar of incense. This cleansed the priests, people and the temple building from all impurity and sin which may have contaminated them during the last year. Having finished the sprinkling, the high priest laid hands on the goat “for Azazel”, handing over to it all the sins of the people. It was then taken out into the desert and thrown off a cliff, symbolically ridding the whole population of their sins.

The last feast that concerns us is the feast of Tabernacles, which lasted seven days and was often referred to simply as “the feast”. It was a time of rejoicing, feasting and processions.. The people lived during those days in temporary huts made from branches and remembered their nomadic past with Moses in the desert and their dependence on God. Possibly originally the feast was held to bring rain and fertility on the land, but it expanded to celebrate God’s kingship over the earth, the covenant between God and the Jewish People, and to petition God for the coming of the Messiah.

The covenant was likened to a marriage between God and his bride, the People of Israel, in which the Law of Moses was the marriage contract, the altar was the place where the two came together, and sacrifice was the marriage act. Each day during the feast there was a procession. Beforehand, the people had covered the great altar of sacrifice with greenery and then they processed round it carrying branches. On the seventh day, they processed round the altar seven times singing psalm 117 (118). When they came to the verse: “Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord. Hosanna in the highest!”, they repeated it three times in a shout, and they waved their branches.

Christ’s entry into Jerusalem appears to be a description of the festivities on this feast; though it can’t be if the true timetable of the Passion is anything like that of the Gospels. This feast, together with the Passover and the Atonement are going to influence Christian theology a lot especially our theology of the Eucharist which is our Pasch, our Atonement and our participation in the marriage feast of the Lamb..

Of course, 70AD was not the first time the Jews were without sacrifices. There was the Babylonian Captivity and, much later, making the temple pagan with the full connivance of the priests caused the rebellion of the Macabees. Psalm 50 (49) tells us that sacrifices by themselves meant nothing. They only had value in so far as they expressed the religious obedience of those who offered them. It says, “Do I eat the flesh of bulls or drink the blood of goats? Offer to God a sacrifice of thanksgiving” (or) “make thanksgiving your sacrifice to God”. Psalm 51 (50) says, “You have no delight in sacrifice; if I were to give you a burnt-offering, you would not be pleased. The sacrifice acceptable to God is a broken spirit; a broken and contrite heart, O God, you will not despise.” There were also many protests by the prophets against a system of sacrifices which had become a substitute for self-offering instead of the ritual expression of self-offering by those who offered sacrifices in the temple. Cardinal Ratzinger has written on this subject:

Among the prophets before the exile, there was an extraordinarily harsh criticism of temple worship, which Stephen, to the horror of the doctors and priests of the temple, resumes in his great discourse, with some citations, notably this verse of Amos: “Did you offer victims and sacrifices to Me, during forty years in the desert, house of Israel? But you have carried the tent of Moloch and the star of the god Rephan, the images which you had made to worship” (Amos 5; 25, Acts 7; 42). This critique that the Prophets had made provided the spiritual foundation that enabled Israel to get through the difficult time following the destruction of the Temple, when there was no worship. Israel was obliged at that time to bring to light more deeply and in a new way what constitutes the essence of worship, expiation, sacrifice. In the time of the Hellenistic dictatorship, when Israel was again without temple and without sacrifice, the book of Daniel gives us this prayer: “Lord, see how we are the smallest of all the nations...There is no longer, at this time, leader nor prophet...nor holocaust, sacrifice, oblation, nor incense, no place to offer You the first fruits and find grace close to You. But may a broken soul and a humbled spirit be accepted by You, like holocausts of rams and bulls, like thousands of fattened lambs; thus may our sacrifice be before You today, and may it please You that we may follow You wholeheartedly, because there is no confounding for those who hope in You. And now we put our whole heart into following You, to fearing You and seeking Your Face” (Dan. 3; 37-41).

Thus gradually there matured the realisation that prayer, the word, the man at prayer and becoming himself word, is the true sacrifice. The struggle of Israel could here enter into fruitful contact with the search of the Hellenistic world, which itself was looking for a way to leave behind the worship of substitution, of the immolation of animals, in order to arrive at worship properly so called, at true adoration, at true sacrifice. This path led to the idea of logike tysia – of the sacrifice [consisting] in the word – which we meet in the New Testament in Rm. 12; 1, where the Apostle exhorts the believers “to offer themselves as a living sacrifice, holy and pleasing to God:” it is what is described as logike latreia, as a divine service according to the word, engaging the reason. We find the same thing, in another form, in Heb. 13; 15: “Through Him – Christ – let us offer ceaselessly a sacrifice of praise, that is to say the fruit of the lips which confess His name.” Numerous examples coming from the Fathers of the Church show how these ideas were extended and became the point of junction between Christology, Eucharistic faith and the putting into existential practice of the paschal mystery. I would like to cite, by way of example, just a few lines of Peter Chrysologos; really, one should read the whole sermon in question in its entirety in order to be able to follow this synthesis from one end to the other:

“It is a strange sacrifice, where the body offers itself without the body, the blood without the blood! I beg you – says the Apostle – by the mercy of God, to offer yourselves as a living victim. Brothers, this sacrifice is inspired by the example of Christ, who immolated His Body, so that men may live...Become, man, become the sacrifice of God and his priest...God looks for faith, not for death. He thirsts for your promise, not your blood. Fervour appeases Him, not murder.”

.

Nevertheless, the problem remained. A “broken and contrite heart” is needed; but it belongs, not to the relationship between God and the People, but between God and the individual Jew. It is not a social act, so the question still remained: Now that the temple is no more, how can God be present to the people as a whole, so that they, as a people, can share in a covenant relationship with him? Also, how can God be approached by the people? How can there be a communal, social liturgy that expresses God’s relationship with his People which, at the same time, will be a liturgy of the heart, now that there are no temple sacrifices? How can there be a sacrifice which is both a sacrifice of the Church and a sacrifice of love, as the psalms and the prophets require? We are now ready to look at the passage from the Book of Revelation with which we began this chapter.

Then I saw a new heaven and a new earth, for the first heaven and the first earth had passed away, and the sea was no more. And I saw the holy city, the new Jerusalem, coming down out of heaven from God, prepared as a bride for her husband. And I heard a voice from the throne saying, “See the home of God among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them; he will wipe every tear from their eyes. Death will be no more; mourning and crying and pain will be no more, for the first things have passed away.” And the one who was seated on the throne said, “See, I am making all things new.” (Rev, 21,1-5

This is a totally new solution, a new stage in God’s dealings with the human race in which nothing will remain the same. The new Jerusalem is not a building. We have seen the celebration of the heavenly liturgy, which is the main theme of the Book of Revelation. It is centred on the Father and on the risen Christ who is “the Lamb that was slain who is standing” and also is the “Alpha and Omega”, the “Beginning and the End” of everything.. The Jews believed the temple was the reflection of a heavenly reality, as was the whole of Jerusalem, and they believed that they participated in that reality by taking part in the temple activities. However, the heavenly temple and the earthly one remained distinct. What was new, was absolutely new, was that the heavenly Jerusalem was coming down to earth and people on earth would participate directly in the liturgy of heaven. The theme that the heavens are open and not closed is found in many places in the New Testament. Angels and shepherds praise the newly born Jesus; the heavens open after Christ’s baptism; angels and wild beasts of the desert minister to Jesus after his temptations. St Luke would say that the heavenly reality became one with the earthly Church at Pentecost when the Holy Spirit descended on the Church. This is the descent of the heavenly Jerusalem that is described in this passage from the Book of Revelation. The people formed by this liturgy which embraces both heaven and earth is now the substitute for the temple. In fact, every Jewish institution in the Old Testament has been replaced by people under this completely new covenant, firstly Jesus in the Spirit, and then by the community that is the Church which is made up of people in heaven and on earth. In the words we have quoted, it is said of them: “And I heard a voice from the throne saying, “See the home of God among mortals. He will dwell with them; they will be his peoples, and God himself will be with them.” Let us continue with the quotation:

(An angel) (…) came and said to me, ‘Come and I will show you the bride , the wife of the Lamb. And in the Spirit he carried me away to a great, high mountain and showed me the holy city of Jerusalem coming out of heaven from God. It has the glory of God and a radiance like a very rare jewel, like jasper, clear as crystal. (…) And the wall of the city has twelve foundations, and on them are the twelve names of the twelve apostles of the Lamb. (…) I saw no temple in the city, for its temple is the Lord God, the Almighty, and the Lamb. The nations will walk by its light. And the city has no need of sun or moon to shine on it, for the glory of God is its light, and its lamp is the Lamb. The nations will walk by its light, and the kings of the earth will bring their glory into it. (Rev. 21, 9ff)

The new Jerusalem is not about buildings: it is about people, persons in communion, the Church which is founded on the apostles. . This Church is a personal reality, being one body with Christ. This passage is saying that, even in its relationship with Christ, as his bride, it is a personal reality. As we shall see later, the person who received all from Christ and who embraces the whole Church with her love is the Blessed Virgin Mary, the new Eve, the hypostasis of the Church in its relationship with Christ, just as he is the hypostasis of the Church in its relationship to the Father. She is also, personally, the new ark of the covenant.

The unity which Jesus had with the whole human race in all times and places was part of the very meaning of the Incarnation, and not a role the individual Jesus took on as an afterthought during his public life and death. Mary became the mother of all mankind on becoming mother of Christ.

When Jesus approached the Father through his death and resurrection, he did it on behalf of the whole race, and in union with it.. On the cross he was the paschal victim () and High Priest (Hb ch 10 & 12). In St John, Christ was the temple itself (Jn 12, 19;) and, when he had offered himself completely in death, the sign that all was over is that blood and water flowed from his side, as it did from the temple after sacrifices.

There is a universal tradition of the Church Fathers, from Ignatius of Antioch to St Augustine and way beyond, that Jesus is also the altar of the temple. Now the death, resurrection and ascension of Jesus is the means by which the whole universe can share in the life of the Blessed Trinity and in the very joy of God. Jesus did not offer a substitute for himself by using the blood of animals, but shed his own blood, motivated by love of the Father and his love for us.

We too can approach the Father because we are the body of his Son, and his sacrifice becomes our sacrifice in the Eucharist. We participate in this sacrifice, not only by answering the responses but, more profoundly and essentially, by offering ourselves as “a living sacrifice of praise” (EP IV). We are not offering him as a substitute for ourselves because we are becoming “one body and spirit” with him who is offered (EP III), and are thus offered with him and in him. Without his offering, our own offering of ourselves would have no value whatever as a means of approaching God: it is only by our synergy with the Holy Spirit that Christ’s sacrifice becomes our sacrifice and his death, resurrection and ascension become our way to the Father.

Hence, the problems related to the temple and its sacrifices have been solved.

The temple had been replaced, firstly by Jesus himself, and then, after the Ascension, by the Christian community on earth that is united in Christ with the Church in heaven. Because of the unity of the human race, the Church embodies the relationship of the whole human race with God. Hence, it is “the home of God among mortals”. At the time when the Book of Revelation was written, there were no church buildings as such. Christ is our temple and, by means of the Eucharist, Christ’s death and the offering of his blood in the sanctuary of heaven is our sacrifice, our means of approaching God. In the Synoptic Gospels, the Eucharist is seen as a paschal meal’ In the Epistle to the Hebrews the Eucharist is described in terms of the Day of the Atonement, and this probably became dominant after the destruction of the temple, and helped to shape our traditional church architecture and ceremonial. In the Book of Revelation the Eucharist is seen in terms of the Feast of the Tabernacles as the bridal banquet between the Lamb and the Church, a feast which is celebrated both in heaven and on earth.

We must accept all three ways if we wish to have an adequate understanding of the Eucharist. All this is possible because of the descent of heaven on earth at Pentecost. Hence, the main Jewish feasts take on new meaning, a meaning derived from Christ and his Church.

Even though the shape of the liturgy and the structure and words of the prayers show us clearly how Christian liturgical tradition has developed out of the Jewish temple tradition, the clearest visual evidence of this continuity is found in ancient Syrian churches where the altar is separated from the nave by a curtain as the deber was separated from the hekel in the temple. As the high priest used to enter the Holy of Holies once a year to offer the sacrifice of atonement, so the priest enters behind the veil at every Mass to offer the New Testament sacrifice of atonement, while the priestly people take part in the area corresponding to the place where. priests offered incense. The altar is called the "throne" of mercy as was the space between the cherubim in the Holy of Holies where the high priest poured the blood, and Eastern liturgies offer many litanies that ask, "Lord have mercy". This is an account of such a Mass:

Even though the shape of the liturgy and the structure and words of the prayers show us clearly how Christian liturgical tradition has developed out of the Jewish temple tradition, the clearest visual evidence of this continuity is found in ancient Syrian churches where the altar is separated from the nave by a curtain as the deber was separated from the hekel in the temple. As the high priest used to enter the Holy of Holies once a year to offer the sacrifice of atonement, so the priest enters behind the veil at every Mass to offer the New Testament sacrifice of atonement, while the priestly people take part in the area corresponding to the place where. priests offered incense. The altar is called the "throne" of mercy as was the space between the cherubim in the Holy of Holies where the high priest poured the blood, and Eastern liturgies offer many litanies that ask, "Lord have mercy". This is an account of such a Mass:

Meanwhile, in Edessa, the capital of the Kingdom of Urhoy on the borders of Syria and Mesopotamia, a Church was in existence before the end of the first century. In the course of the next two centuries Edessa became the centre of a Christian culture using the Edessene dialect of Aramaic, called Syriac, as its language. While the Church in the West adopted Greek as its language for worship, the Church in the East, addressing itself largely to the Jewish Christians of the diaspora, continued to speak Aramaic. The forms of worship in the Syriac Orthodox Church reflect the Antiochene and Edessene heritage of the Churc

http://sor.cua.edu/WOrship/

The sense of awe and wonder before the divine Mystery pervades the Syriac Church. The Syrian liturgy is dominated by the scene in the vision of the prophet Isaiah, when, he saw the Lord on a high and lofty throne in the temple in Jerusalem, and heard the angels crying, ‘holy, holy, holy’ before him. In every Syriac church there is a ‘veil’ drawn across the sanctuary, representing the veil in the temple of Jerusalem, and the sanctuary itself is held to be the ‘holy of holies’, the place where God himself appears in the New Covenant with his people, This scene is recalled at the beginning and the end of every office of prayer and the sense of wonder and mystery which inspires it fills the whole liturgy. Together with this sense of awe in the presence of the holiness of God is a profound sense of human sin. As the prophet was led to cry out, ‘Woe is me, for I am man a of unclean lips and I dwell among a people of unclean lips’, so the Syriac liturgy is filled with this sense of human sin and unworthiness. One of the principal themes of the liturgy is that of ‘repentance’. But this sense of sin and the need for repentance is accompanied by, or rather an expression of, the awareness of God’s infinite love and mercy, which comes down to man’s need and raises him to share in his own infinite glory. Thus there is a wonderful balance of dreadful majesty and loving compassion, of abasement and exaltation.

No comments:

Post a Comment