The Preacher of the Papal Household, Capuchin Fr. Raniero Cantalamessa delivered the last of his Lenten reflections on Friday morning in the Redemptoris mater chapel of the Apostolic Palace. Dedicated to St. Gregory of Nyssa, Fr. Cantalamessa’s sermon concentrated on the deep affinities between the thinking of the fourth century Church father, and the existential questions of contemporary humanity. Fr. Cantalamessa explained that St Gregory in fact traced a way to knowledge of God that appears to be particularly respondent to the religious situation of man today: the way toward knowledge that passes through unknowing. In this way, St. Gregory contributed significantly to the development of theological reflection on mystical experience, and also to the development of the notion of the cognition of faith – that the highest part of the person, reason, is not excluded from the search for God – that one is not forced to choose between following faith and following intelligence. “By believing,” said Fr. Cantalamessa, “the human person does not give up his rationality but transcends it, which is something very different. It stretches the resources of reason to the extreme, permitting it to perform its most noble act.” Listen to our report:

Below, please find the full text of Fr. Cantalamessa's sermon in English.

Father Raniero Cantalamessa, ofmCap.Fourth Lenten Homily

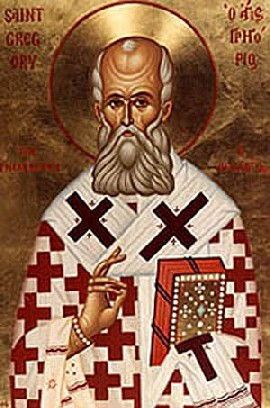

SAINT GREGORY OF NYSSA

AND THE WAY TO KNOW GOD

1. The Two Dimensions of FaithIn regard to faith, Saint Augustine made a distinction which has remained classic up to today: the distinction between things that are believed and the act of believing in them: “Aliud sunt ea quae creduntur, aliud fides qua creduntur”[1], the fidea quae and the fides qua, as is said in theology. The first is also said to be objective faith, the second faith is subjective. All Christian reflection on faith takes place between these two poles.

Delineated are two orientations, with different names and accentuations. On one hand we have those who accentuate the importance of the intellect in believing, hence, objective faith, as assent to revealed truths, on the other, those who accentuate the importance of the will and affection, hence, subjective faith, to believe in someone (“to believe in”), rather than believing something (“believe that”) -- on one hand, those who accentuate the reasons of the mind and, on the other, those that, as Pascal, accentuate “the reasons of the heart.”

This oscillation reappears in different forms at every turn of the history of theology: in the Medieval Age, in the different accentuation between the theology of Saint Thomas and that of Saint Bonaventure; at the time of the Reformation between the faith-trust of Luther and the Catholic faith informed by charity; later between Kant’s faith in the limits of simple reason and faith founded on the sentiment of Schleiermacher and of Romanticism in general; and, closer to us, between the faith of liberal theology and Bultmann’s existential theology, practically devoid of all objective content.

Contemporary Catholic theology makes an effort, as in other times in the past, to find the right balance between the two dimensions of faith. The phase has been surmounted in which, for contingent controversial reasons, the whole attention of theology manuals ended up by concentrating on objective faith (fides quae), that is, on the set of truths to be believed. “The act of faith -- one reads in an authoritative critical dictionary of theology -- in the prevailing current of all Christian confessions, appears today as the discovery of a divine You. Hence, the apologetics of proof tends to situate itself behind a pedagogy of spiritual experience that tends to initiate to a Christian experience, the possibility of which is recognized inscribed a priori in every human being.”[2] In other words, more than appealing to the person on the strength of external arguments, what is sought is to help him find in himself the confirmation of the faith, seeking to rekindle that spark which is in the “restless heart” of every man by the fact of being created “in the image of God.”

I made this introduction because once again it enables us to see the contribution that the Fathers can make to our effort to give back to the faith of the Church its splendor and impetus. The greatest among them are unsurpassed models of a faith that is both objective and subjective, concerned, that is, about the content of the faith, namely, its orthodoxy but, at the same time believed and lived with all the ardor of the heart. The Apostle Paul proclaimed: “corde creditor” (Romans 10:10), one believes with the heart, and we know that with the word heart, the Bible understands both spiritual dimensions of man, his intelligence and his will: the heart is the symbolic place of knowledge and love. In this sense the Fathers are an indispensable link to rediscover the faith as Scripture intends it.

2. “I believe in one God”

In this last meditation we approach the Fathers to renew our faith in its primary object, in what is commonly understood with the word “believe” and on the basis of which we distinguish persons between believers and non-believers: faith in the existence of God. In the preceding meditations we reflected on the divinity of Christ, on the Holy Spirit and on the Trinity. However, faith in the Triune God is the final stage of faith, the “more” on God revealed by Christ. To attain this fullness it is necessary first to believe in God. Before faith in the Triune God, there is faith in the One God.

Saint Gregory of Nazianzen reminded us of God’s pedagogy in revealing himself gradually. First, in the Old Testament, the Father is revealed openly and the Son, then, in the New, the Son is revealed openly and the Holy Spirit in a veiled way, now, in the Church, the whole Trinity is revealed openly. Jesus also says that he refrains from telling the Apostles those things of which they are still unable to “bear the weight” (John 16:12). We must also follow the same pedagogy in addressing those to whom we wish to proclaim the faith today.

The Letter to the Hebrews says what the first step is to approach God: “For whoever would draw near to God must believe that he exists and that he rewards those who seek him” (Hebrews 11:6). This is the foundation of all the rest that remains, also after having believed in the Trinity. Let us see how the Fathers can be of inspiration to us from this point of view, always keeping present that our main purpose is not apologetic but spiritual, oriented, that is, to consolidate our faith, more than to communicate it to others. The guide we choose for this path is Saint Gregory of Nyssa.

Gregory of Nyssa (331-394), blood brother of Saint Basil, friend and contemporary of Gregory of Nazianz, is a Father and Doctor of the Church, whose intellectual stature and decisive importance in the development of Christian thought is being discovered ever more clearly. He is “one of the most powerful and original thinkers known in the history of the Church” (L. Bouyer), “the founder of a new mystical and ecstatic religiosity” (H. von Campenhausen).

Unlike us, the Fathers did not have to demonstrate the existence of God, but the oneness of God; they did not have to combat atheism but polytheism. We will see, however, how the path traced by them to attain knowledge of the one God is the same one that can lead the man of today to the discovery of God tout court.

To assess the contribution of the Fathers and, in particular, of Gregory of Nyssa, it is necessary to know how the problem of the oneness of God presented itself at the time. While the doctrine of the Trinity was being affirmed, Christians saw themselves exposed to the same accusation that they had always addressed to pagans: that of believing in more divinities. Here is why the creed of Christians, which for three centuries, in all its various formulations, began with the words “I believe in God” (Credo un Deum), beginning in the 4th century, registers a small but significant addition which would never be omitted afterwards: “I believe in one God” (I believe in unum Deum).

It is not necessary to go over the path again here that led to this result; we can begin from its conclusion. Concluded toward the end of the 4th century was the transformation of the monotheism of the Old Testament into the Trinitarian monotheism of Christians. The Latins expressed the two aspects of the mystery with the formula “one substance and three persons,” the Greeks with the formula “three hypostasis, only one ousia.” After a long confrontation, the process concluded apparently with a total agreement between the two theologies. “Can one conceive -- exclaimed Gregory of Nazianz -- a fuller agreement and say more absolutely the same thing, even if with different words?”[3]

In reality a difference remained between the two ways of expressing the mystery. Today it is usual to express it thus: in the consideration of the Trinity, the Greeks and the Latins move from opposite sides: the Greeks begin from the divine persons, namely from plurality, to attain the unity of nature; and, vice versa, the Latins begin from the unity of the divine nature, to arrive at the three persons. “The Latin considers the personality as a way of the nature; the Greek considers the nature as the content of the person.”[4]

I think the difference can be expressed in another way. Both Latins and Greeks begin from the unity of God. Both the Greek and the Latin symbol begin saying “I believe in one God” (Credo in unum Deum”!). Only that for the Latins this unity is conceived as impersonal or pre-personal; it is the essence of God that is specified then in Father, Son and Holy Spirit, without, of course, being thought as pre-existing to the persons. For the Greeks, instead, it is a unity that is already personalized, because for them “the unity is the Father from whom and to whom the other persons are counted.”[5] The first article of the Greek Creed also says this ”I believe in one God the Father almighty” (Credo in unum Deum Patrem omnipotentem”), only that here “the Father almighty” is not detached from ‘unum Deum,’ as in the Latin Creed, but it makes a whole with it: I believe in one God who is the Almighty Father.”

This was the way all three Cappadocians conceived the oneness of God, but more than all of them Saint Gregory of Nyssa. For him, the unity of the three divine persons is given by the fact that the Son is perfectly (substantially) “united” to the Father, as is also the Holy Spirit through the Son.”[6] It is, in fact, this thesis that creates a difficulty for the Latins who see in it the danger of subordinating the Son to the Father and the Spirit to one and the other: “The name ‘God’ -- wrote Augustine -- indicates the whole Trinity, not just the Father.”[7]

God is the name we give the divinity when we consider it not in itself, but in relation to men and to the world, because all that it does outside of itself it does together, as one sole efficient cause. The important conclusion we can draw from all this, apart from the different point of departure of Latins and Greecs, is that the Christian faith is also monotheistic; Christians have not given up the Jewish faith in one God, rather, they have enriched it, giving content and a new and marvelous sense to this unity. God is one, but not solitary!

3. “Moses entered the cloud”

Why choose Saint Gregory of Nyssa as guide in knowledge of this God in front of whom we stay as creatures before the Creator? The reason is that this Father, first of all in Christianity, has traced a way to knowledge of God that appears to be particularly respondent to the religious situation of the man of today: the way of knowledge that passes through … non-knowledge.

The occasion was offered to him by the controversy with the heretic Eunomius, the representative of a radical Arianism against whom all the great Fathers wrote who lived in the last period of the 4th century: Basil, Gregory of Nazianz, Chrysostom and, more acutely than all, Gregory of Nyssa. Eunomius identified the divine essence in the fact of being “un-begotten” (agennetos). In this connection, for him it was perfectly knowable and did not represent a mystery; we can know God no less than he knows himself.

The Fathers reacted as one, holding the thesis of the “incomprehensibility of God” in his intimate reality. But while the others halted at a confutation of Eunomius, based more than anything on the words of the Bible, Gregory of Nyssa, went beyond demonstrating that precisely the recognition of this incomprehensibility is the way to the true knowledge (theognosia) of God. He did so taking up a theme already sketched by Philo of Alexandria[8]: that of Moses who encounters God on entering the cloud. The biblical text is Exodus 24:15-18 and here is his comment:

“The manifestation of God happens first for Moses in the light; then He spoke with him in the cloud, finally having become more perfect, Moses contemplates God in the darkness. The passage from darkness to light is the first separation of the false and erroneous ideas about God; the intelligence more attentive to hidden things, leading the soul through visible things to the invisible reality, is like a cloud that darkens all the sensible and accustoms the soul to the contemplation of what is hidden; finally the soul that has walked on this path toward heavenly things, having left earthly things in so far as possible to human nature, penetrates the sanctuary of divine knowledge (theognosia) surrounded from all sides by the divine darkness.”[9]

True knowledge and the vision of God consist “in seeing that He is invisible, because He whom the soul seeks transcends all knowledge, separated from every part by his incomprehensibility as by a darkness.”[10]

In this final stage of knowledge, there is no concept of God, but that which Gregory of Nyssa, with an expression that has become famous, defines as “a certain feeling of presence” (aisthesin tina tes parusias).[11] A feeling not with the senses of the body, it is understood, but with the interior ones of the heart. This feeling does not go beyond faith but is its highest accomplishment. “With faith -- exclaims the Bride of the Canticle (Canticle 3:6) -- I have found the Beloved.” She does not “understand” him”; she does better, she “holds” him![12]

These ideas of Gregory of Nyssa had an immense influence on subsequent Christian thought, to the point of his being considered the very founder of Christian mysticism. Through Dionysius the Areopagite and Maximus the Confessor who take up his theme, his influence spread from the Greek world to the Latin. The subject of the knowledge of God in darkness returns in Angela of Foligno, in the author of the Cloud of Unknowing, in the subject of “learned ignorance” of Nicolas Cusanus, and in that of the “dark night” of John of the Cross and in many others.

4. Who really humiliates reason?

Now I would like to show how Saint Gregory of Nyssa’s intuition can help us, believers, to deepen our faith and to indicate to modern man, who has become skeptical of the “five ways” of traditional theology, to rediscover a path that leads him to God.

The novelty introduced by Gregory of Nyssa in Christian thought is that to encounter God it is necessary to go beyond the confines of reason. We are at the antipodes of Kant’s plan to keep religion “within the confines of simple reason.” In today’s secularized culture we have gone beyond Kant: in the name of reason (at least practical reason) he “postulated” the existence of God, subsequent rationalists even deny this.

From this we understand how timely Gregory of Nyssa’s thought it. He demonstrates that the highest part of the person, reason, is not excluded from the search for God; that we are not constrained to choose between following the faith and following the intelligence. Entering the cloud, that is, by believing, the human person does not give up his rationality but transcends it, which is something very different. It stretches the resources of reason to the extreme, permitting it to perform its most noble act, because, as Pascal affirms, “the supreme act of reason lies in recognizing that there is an infinity of things that surpass it.”[13]

Saint Thomas Aquinas, rightly considered one of the most strenuous defenders of the exigencies of reason, wrote: “It is said that at the end of our knowledge, God is known as the Unknown because our spirit has arrived at the extreme of its knowledge of God when in the end it understands that his essence is beyond all that which it can know down here.”[14]

In the very instant that reason recognizes its limit, it breaks through it and surpasses it. It understands that it cannot understand, “it sees that it cannot see,” said Gregory of Nyssa, but it also understands that a comprehensible God would no longer be God. It is the work of reason that produces this recognition which is, because of this, an exquisitely rational act. It is, to the letter, a “learned ignorance.”[15]

Hence, what should be said, instead, is the contrary, the one who puts a limit to reason and humiliates it is he who does not recognize its capacity to transcend itself. “Up to now -- wrote Kierkegaard -- we have always spoken thus: ‘To say that one cannot understand this or that thing does not satisfy science which wants to understand.’ Here is the mistake. In fact, the contrary should be said: if human science does not want to recognize that there is something that it cannot understand, or -- in a still more precise way -- something of which with clarity it can ‘understand that it cannot understand,’ then everything is thrown into confusion. Hence it is a task of human knowledge to understand that there are, and to identify which are, the things that it cannot understand.”[16]

However, what sort of darkness is this? It is said of the cloud that, at a certain point, interposed itself between the Egyptians and the Jews, that it was “dark for some and luminous for others” (cf. Exodus 14:20). The world of faith is dark for one who looks at it from outside, but it is luminous for one who goes inside, a special luminosity, of the heart more than of the mind. In the Dark Night of Saint John of the Cross (a variant of Gregory of Nyssa’s theme of the cloud!) the soul declares it is proceeding on its new path,

“without any other guide and light than the one that shines in my heart.” A light, however, that is “more luminous than the sun at midday.”[17]

Blessed Angela of Foligno, one of the highest representatives of the vision of God in darkness, says that the Mother of God “was so ineffably united to the total and absolutely ineffable Trinity, that in life she enjoyed the joy that the saints enjoy in heaven, the joy of incomprehensibility (Gaudium incomprehensibilitatis), because they understand that it cannot be understood.”[18]

It is a stupendous complement to the doctrine of Gregory of Nyssa on the unknowability of God. It assures us that far from humiliating us and depriving us of something, this unknowability is made to fill man with enthusiasm and joy; it tells us that God is infinitely greater, more beautiful, more good than we can think, and that all this is for us, so that our joy will be full and we will never be touched by the thought that we will be bored in spending eternity with him!

Another idea of Gregory of Nyssa, which is useful for a comparison with modern religious culture, is that of the “feeling of a presence” that he puts at the summit of knowledge of God. Religious phenomenology has brought to light the existence of a primary fact, present in different degrees of purity, in all the cultures and in all the ages that he calls “feeling of the numinous,” that is the sense, mixed with terror and attraction, which grips the human being suddenly in face of the manifestation of the supernatural and the super-rational.[19] If the defense of the faith, according to the latest guidelines of apologetics recalled at the beginning, “is placed behind a pedagogy of spiritual experience, of which the possibility is recognized inscribed a priori in every human being,” we cannot neglect the link that modern religious phenomenology offers us.

Certainly, the “feeling of a certain presence” of Gregory of Nyssa is different from the confused sense of the numinous and the thrill of the supernatural, but the two things have something in common. One is the beginning of a path toward the discovery of the living God, the other is the end. Knowledge of God, said Gregory of Nyssa, begins with the passing from darkness to light and ends with the passing from light to darkness. The second passage is not attained without passing through the first; in other words, without first being purified from sin and the passions. “I would already have abandoned pleasures -- says the libertine -- if I had faith. But I respond, says Pascal: You would already have faith if you had abandoned pleasures.”[20]

The image that accompanied us in the whole of this meditation, thanks to Gregory of Nyssa, was that of Moses who goes up to mount Sinai and enters the cloud. The proximity of Easter pushes us to go beyond this image, to pass from the symbol to the reality. There is another mount where another Moses has encountered God while “there was darkness over all the land” (Matthew 27:45). On Mount Calvary the man-God, Jesus of Nazareth, united man forever with God. At the end of his Journey of the Mind to God, Saint Bonaventure writes:

“After all these considerations, what stays in our mind is to elevate it speculating not only beyond this sensible world, but also beyond itself; and in this ascent Christ is the way and door, Christ is ladder and vehicle … He who looks attentively at this propitiation hanging on the cross, with faith, hope and charity, with devotion, admiration, exultation, veneration, praise and rejoicing celebrates Easter with him, that is, the passage.”[21]May the Lord grant us to make this beautiful and holy “Passover” with him!--- --- ---

1. Augustine, De Trinitate, XIII, 2, 5.2. J. Y. Lacoste and N. Lossky, “Fois,” in Dictionnaire critique de Theologie, Presses Universitaires de France, 1988, p. 479.

3. Gregory of Nazianzen, Oratio 42, 16 (PG 36, 477).4. Th. De Regnon, Etudes de theologie positive sur la Sainte Trinité, I, Paris 1892, 433.

5. Saint Gregory of Nazianzen, Oratio 42, 15 (PG 36, 476).6. Cf. Gregory of Nyssa, Contra Eunomium 42 (PG 45, 464).

7. Augustine, De Trinitate, I6,10; cf. also IX,1,1 (“credamus Patrem et Filium et Spiritum Sanctum esse unum Deum”).8. Cf. Philo Al., De posteritate, 5, 15.

9. Gregory of Nyssa, Homily XI on the Canticle )(PG 44, 1000 C-D).10. Life of Moses, II, 163 (SCh 1 bis, p. 210 f.).

11. Homily XI on the Canticle (PG 44, 1001 B).12. Homily on the Canticle (PG 44, 893 B-C).

13. B. Pascal, Pensees 267 Br.14. Thomas Aquinas, In Boet. Trin. Proem., q. 1, a.2, to 1.

15. Augustine, Epistle 130, 28 (PL 33, 505).16. S. Kierkegaard, Diary VIII A 11.

17. John of the Cross, Dark Night, Song of the Soul, stanza 3-418. Il libro della beata Angela da Foligno, Quaracchi publishers, 1985, p. 468.

19. R. Otto, The Idea of the Holy (1923), Oxford University Press.20. Pascal, Pensees, 240 Br.

21. Bonaventure, Itinerarium mentis in Deum, VII, 1-2 (Opere de S. Bonaventura, V, 1, Rome, Citta Nuova, 1993, p. 564.

please click on:

THREE LECTURES BY METROPOLITAN KALLISTOS WARE

CAMBRIDGE FORUM

SAINT MACRINA by St Gregory of Nyssa & THE CAPPADOCIANS

SAINT MACRINA by St Gregory of Nyssa & THE CAPPADOCIANS

BENEDICT XVI

GENERAL AUDIENCE

Saint Peter's Square

Wednesday, 13 October 2010

Blessed Angela of Foligno

Dear Brothers and Sisters,

Today I would like to speak to you about Blessed Angela of Foligno, a great medieval mystic who lived in the 13th century. People are usually fascinated by the consummate experience of union with God that she reached, but perhaps they give too little consideration to her first steps, her conversion and the long journey that led from her starting point, the "great fear of hell", to her goal, total union with the Trinity. The first part of Angela's life was certainly not that of a fervent disciple of the Lord. She was born into a well-off family in about 1248. Her father died and she was brought up in a somewhat superficial manner by her mother. She was introduced at a rather young age into the worldly circles of the town of Foligno, where she met a man whom she married at the age of 20 and to whom she bore children. Her life was so carefree that she was even contemptuous of the so-called "penitents", who abounded in that period; they were people who, in order to follow Christ, sold their possessions and lived in prayer, fasting, in service to the Church and in charity.

Certain events, such as the violent earthquake in 1279, a hurricane, the endless war against Perugia and its harsh consequences, affected the life of Angela who little by little became aware of her sins, until she took a decisive step. In 1285 she called upon St Francis, who appeared to her in a vision and asked his advice on making a good general Confession. She then went to Confession with a Friar in San Feliciano. Three years later, on her path of conversion she reached another turning point: she was released from any emotional ties. In the space of a few months, her mother's death was followed by the death of her husband and those of all her children. She therefore sold her possessions and in 1291 enrolled in the Third Order of St Francis. She died in Foligno on 4 January 1309.

The Book of Visions and Instructions of Blessed Angela of Foligno, in which is gathered the documentation on our Blessed, tells the story of this conversion and points out the necessary means: penance, humility and tribulation; and it recounts the steps, Angela's successive experiences which began in 1285. Remembering them after she had experienced them, Angela then endeavoured to recount them through her Friar confessor, who faithfully transcribed them, seeking later to sort them into stages which he called "steps or mutations" but without managing to put them entirely in order (cf. Il Libro della beata Angela da Foligno, Cinisello Balsamo 1990, p. 51). This was because for Blessed Angela the experience of union meant the total involvement of both the spiritual and physical senses and she was left with only a "shadow" in her mind, as it were, of what she had "understood" during her ecstasies. "I truly heard these words", she confessed after a mystical ecstasy, but it is in no way possible for me to know or tell of what I saw and understood, or of what he [God] showed me, although I would willingly reveal what I understood with the words that I heard, but it was an absolutely ineffable abyss". Angela of Foligno presented her mystical "life", without elaborating on it herself because these were divine illuminations that were communicated suddenly and unexpectedly to her soul. Her Friar confessor too had difficulty in reporting these events, "partly because of her great and wonderful reserve concerning the divine gifts" (ibid., p. 194). In addition to Angela's difficulty in expressing her mystical experience was the difficulty her listeners found in understanding her. It was a situation which showed clearly that the one true Teacher, Jesus, dwells in the heart of every believer and wants to take total possession of it. So it was with Angela, who wrote to a spiritual son: "My son, if you were to see my heart you would be absolutely obliged to do everything God wants, because my heart is God's heart and God's heart is mine". Here St Paul's words ring out: "It is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me" (Gal 2: 20).

Let us then consider only a few "steps" of our Blessed's rich spiritual journey. The first, in fact, is an introduction: "It was the knowledge of sin", as she explained, "after which my soul was deeply afraid of damnation; in this stage I shed bitter tears" (Il Libro della beata Angela da Foligno, p. 39). This "dread" of hell corresponds to the type of faith that Angela had at the time of her "conversion"; it was a faith still poor in charity, that is, in love of God. Repentance, the fear of hell and penance unfolded to Angela the prospect of the sorrowful "Way of the Cross", which from the eighth to the 15th stages was to lead her to the "way of love". Her Friar confessor recounted: "The faithful woman then told me: I have had this divine revelation: "after the things you have written, write that anyone who wishes to preserve grace must not lift the eyes of his soul from the Cross, either in the joy or in the sadness that I grant or permit him'" (ibid., p. 143). However, in this phase Angela "did not yet feel love". She said: "The soul feels shame and bitterness and does not yet feel love but suffering" (ibid., p. 39), and is unrequited.

Angela felt she should give something to God in reparation for her sins, but slowly came to realize that she had nothing to give him, indeed, that she "was nothing" before him. She understood that it would not be her will to give her God's love, for her will could give only her own "nothingness", her "non-love". As she was to say: only "true and pure love, that comes from God, is in the soul and ensures that one recognizes one's own shortcomings and the divine goodness.... Such love brings the soul to Christ and it understands with certainty that in him no deception can be found or can exist. No particle of worldly love can be mingled with this love" (ibid., p. 124-125). This meant opening herself solely and totally to God's love whose greatest expression is in Christ: "O my God" she prayed, "make me worthy of knowing the loftiest mystery that your most ardent and ineffable love brought about for our sake, together with the love of the Trinity, in other words the loftiest mystery of your most holy Incarnation.... O incomprehensible love! There is no greater love than this love that brought my God to become man in order to make me God" (ibid., p. 295). However, Angela's heart always bore the wounds of sin; even after a good Confession she would find herself forgiven and yet still stricken by sin, free and yet conditioned by the past, absolved but in need of penance. And the thought of hell accompanied her too, for the greater the progress the soul made on the way of Christian perfection, the more convinced it is not only of being "unworthy" but also deserving of hell.

And so it was that on this mystical journey Angela understood the central reality in a profound way: what would save her from her "unworthiness" and from "deserving hell" would not be her "union with God" or her possession of the "truth" but Jesus Crucified, "his crucifixion for me", his love.

In the eighth step, she said, "However, I did not yet understand whether my liberation from sins and from hell and conversion to penance was far greater, or his crucifixion for me" (ibid., n. 41). This was the precarious balance between love and suffering, that she felt throughout her arduous journey towards perfection. For this very reason she preferred to contemplate Christ Crucified, because in this vision she saw the perfect balance brought about. On the Cross was the man-God, in a supreme act of suffering which was a supreme act of love. In the third Instruction the Blessed insisted on this contemplation and declared: "The more perfectly and purely we see, the more perfectly and purely we love.... Therefore the more we see the God and man, Jesus Christ, the more we are transformed in him through love.... What I said of love... I also say of suffering: the more the soul contemplates the ineffable suffering of the God and man Jesus Christ the more sorrowful it becomes and is transformed through suffering" (ibid., p. 190-191). Thus, unifying herself with and transforming herself into the love and suffering of Christ Crucified, she was identifying herself with him. Angela's conversion, which began from that Confession in 1285, was to reach maturity only when God's forgiveness appeared to her soul as the freely given gift of the love of the Father, the source of love: "No one can make excuses", she said, "because anyone can love God and he does not ask the soul for more than to love him, because he loves the soul and it is his love" (ibid., p. 76).

On Angela's spiritual journey the transition from conversion to mystical experience, from what can be expressed to the inexpressible, took place through the Crucified One. He is the "God-man of the Passion", who became her "teacher of perfection". The whole of her mystical experience, therefore, consisted in striving for a perfect "likeness" with him, through ever deeper and ever more radical purifications and transformations. Angela threw her whole self, body and soul, into this stupendous undertaking, never sparing herself of penance and suffering, from beginning to end, desiring to die with all the sorrows suffered by the God-man crucified in order to be totally transformed in him. "O children of God", she recommended, "transform yourselves totally in the man-God who so loved you that he chose to die for you a most ignominious and all together unutterably painful death, and in the most painful and bitterest way. And this was solely for love of you, O man!" (ibid., p. 247). This identification also meant experiencing what Jesus himself experienced: poverty, contempt and sorrow, because, as she declared, "through temporal poverty the soul will find eternal riches; through contempt and shame it will obtain supreme honour and very great glory; through a little penance, made with pain and sorrow, it will possess with infinite sweetness and consolation the Supreme Good, Eternal God" (ibid., p. 293).

From conversion to mystic union with Christ Crucified, to the inexpressible. A very lofty journey, whose secret is constant prayer. "The more you pray", she said, "the more illumined you will be and the more profoundly and intensely you will see the supreme Good, the supremely good Being; the more profoundly and intensely you see him, the more you will love him; the more you love him the more he will delight you; and the more he delights you, the better you will understand him and you will become capable of understanding him. You will then reach the fullness of light, for you will understand that you cannot understand" (ibid., p. 184).

Dear brothers and sisters, Blessed Angela's life began with a worldly existence, rather remote from God. Yet her meeting with the figure of St Francis and, finally, her meeting with Christ Crucified reawakened her soul to the presence of God, for the reason that with God alone life becomes true life, because, in sorrow for sin, it becomes love and joy. And this is how Blessed Angela speaks to us. Today we all risk living as though God did not exist; he seems so distant from daily life. However, God has thousands of ways of his own for each one, to make himself present in the soul, to show that he exists and knows and loves me. And Blessed Angela wishes to make us attentive to these signs with which the Lord touches our soul, attentive to God's presence, so as to learn the way with God and towards God, in communion with Christ Crucified. Let us pray the Lord that he make us attentive to the signs of his presence and that he teach us truly to live. Thank you.

A CATHOLIC COMPARISON BETWEEN ST FRANCIS OF ASSISI AND ST SERAPHIM OF SAROV.

Some Orthodox (and Catholics too) rush in where angels fear to tread, judging not only the works of men but also the works of God. Anyone who has taken part in ecumenical discussion knows how difficult it is to enter the spiritual world of another tradition, to see it through the eyes of the other in order to understand it, while maintaining our spiritual independence in order to evaluate it according to our own Tradition, doing all this in a spirit of prayer. These people do not see the need for such an exercise because their ecclesial love and, therefore, their ecclesial understanding, do not extend beyond the borders of their own church. Orthodox or Catholic they may be, but their minds are sectarian, damaged by the schism which they didn't bring about, which is not their fault, but which is the most obscene in history.

A good example of this kind of polemic writing is "A Comparison: Francis of Assisi and St. Seraphim of Sarov," from the Orthodox Christian Information Center. I shall content myself with a few quotations and commenting on them; but first I want to draw your attention to a couple of quotations from two other Catholic saints from the above two articles.

Father Raniero Cantalamessa writes about the moment one realises that one does not know God, that God is infinitely above our very capacity to know - not a theoretical knowledge you can learn from o book, but an experiential knowledge and experience of "the cloud of unknowing." He says,

While St John of the Cross is talking about knowledge, St Angela de Foligno, a disciple of St Francis of Assisi, talks about this paradox of understanding and love - the doctrine is the same:

We shall now look at the Orthodox post under discussion. Here is a quotation which shows the ignorance of the writer.

Studying the biographical data of Francis of Assisi, a fact of the utmost interest concerning the mysticism of this Roman Catholic ascetic is the appearance of stigmata on his person. Roman Catholics regard such a striking manifestation as the seal of the Holy Spirit. In Francis' case, these stigmata took on the form of the marks of Christ's passion on his body.

In fact, we see the common Tradition of the Catholic Church, we can look at the above two posts. The unusual experience of St Francis of Assisi - there were many copycat mystics after him whose sanctity was not recognised by the Church - must be interpreted in the light of that Tradition, rather than the other way round.

There comes a moment in the life of Christian mystics that is a great turning point. However hard they have tried to know God, however hard they have strived to love God, however hard they have tried to pray, they arrive at an experience of the sheer immensity of God that is, at the same time, a dark cloud and a bright light. Looking at themselves, they see that God is way beyond any possibility of our knowing him, way beyond our efforts to love him, so that, in St Angela de Foligno's words, it is an "unlove", and that in trying to pray to him we have set ourselves an impossible task. Our efforts, working in synergy with the Holy Spirit, have led us to this point. Our knowledge is ignorance, our love is unworthy of God, and our prayer has become an ineffectual tapping on a closed door. "God, my God, why have you abandoned me?"

We have all experienced this at times; but what makes this moment special is that the experience of our total inadequacy comes from our encounter with the Real Thing. God is transforming us. God's Reality is hitting us between the eyes. What is making us realise our weakness and brings us to the brink of agnosticism is not our lack of communication with the Most High, but the excess of our contact. As we realise the total inadequacy of our knowledge of God, we become aware that we are becoming participants in God's knowledge of God; as we realise that our love is totally inadequate, so we become aware of the presence within us of Christ's love for his Father which carries us, totally unworthy that we are, into the loving embrace of the Father, and are sharing Christ's love for him; as we recognise the disproportionate weakness of our prayer, an obstacle is removed, and our prayer in the Spirit wells up from the depths of our heart, uniting our prayer to Christ's own prayer. We do not live, but Christ lives in us as, in the words of St John of the Cross, “without any other guide and light than the one that shines in my heart.” A light, however, that is “more luminous than the sun at midday." This is transfiguration, what the Greeks call "theosis".

Of course, all of who participate in the Mass share in the Liturgy of heaven, and Christ celebrates the "liturgy of the heart" deep within us; and, to the degree we humbly obey as we share in the "sacrament of the present moment", the Holy Spirit unites our actions and our prayer in a certain synergy with Christ. However, as Grisha told the adolescent Prokhor who would become St Seraphim of Sarov, there is a barrier between our heart where Christ dwells and our mind, a barrier which can only be broken through, using as a tool the weapon of humble obedience. We remain spiritual schizophrenics with Christ in our heart and the world in our brain until this task is accomplished, and we can then be transfigured through and through by the divine life.

It is in this context that we must interpret the stigmata of St Francis. This is how both St Francis himself interpreted it, and how his disciple, the great theologian St Bonaventure, interpreted it. To do so, they noted the connection between Christ's death on Golgotha and his Transfiguration on Mount Tabor, Tabor illustrating the true glory of the Cross, and the Cross showing us that the light on Mount Tabor is nothing less than the divine-human self-sacrificing love of Christ.

St Bonaventure would have said the phenomenon of being transformed by light in St Seraphim and other Eastern saints and the stigmata in St Francis are different but complementary ways of manifesting theosis. Just as Christ's death and resurrection belong to one another and complement one another, so that you cannot have the crucifixion without the resurrection, and you cannot have the resurrection without the crucifixion, so you cannot have saints transformed by the light of the resurrection without their sharing in the sufferings of the Cross, and you cannot have saints manifesting their sharing in Christ's sufferings without sharing in the light of the resurrection, (though he preferred the word "fire" to "light" because the latter, for him, suggested some kind of intellectual enlightenment, while "fire" suggested intense love reaching out through intellectual darkness beyond where the intellect can go. Apart from the different forms of transfiguration in the two saints, what else was different? For St Bonaventure, who did not have such a detailed knowledge of Catholic Tradition as the Orthodox author of the article we are criticising, he regarded the stigmata of St Francis as completely and absolutely unique, a sign for the times in which they lived: God's message for the 13th century! I shall give you a reference to a much fuller treatment of this subject as the end of this post, well worth reading. For the moment, here are a couple of quotations to illustrate what I have been saying.

This is a quotation from the Fioretti which unites the theme of the stigmata and light:

The whole point of the contemporary fascination with these stigmata was that they were unique. For the Spirituals, he was the angel of the Apocalypse, heralding the New Age of the Holy Spirit. For St Bonaventure who did not believe in a new Age of the Spirit separate from what went before, St Francis was a living icon of Christ, a sign that God was renewing his people; but he put this renewal in the context of the ongoing action of the Holy Spirit in the Church that is the source of Tradition.

Finally, a few remarks on the quotations used in this unfortunate Orthodox article:

firstly, it is important to interpret them, not according to their meaning if Orthodox had said them, but within their proper context.

This means that they are to be interpreted according to their meaning in Catholic teaching, not Orthodox.

To do this properly, it is as important to recognise what is not said but which was too obvious to people within the context, as well as what is said.

St Francis was well known for his humility, but no mention of this is made by the Orthodox author because it would have spoiled the false picture he is constructing. In the quotations he does make, there is as much interpretation as quotation in favour of his own reading of history: it isn't trustworthy.

Nicholas Zernov had the advantage of knowing both Eastern Orthodox and Western Catholic traditions, and hence could draw a close parallel between St Seraphim and St Francis. St Ignaty Bianchaninov - I am not going to insult him like the Orthodox author of the article who called St Francis a "papist fanatic", because both were saints, the clasp of whose sandals neither he nor I are worthy to loose - was not an expert on Catholicism and, forgetting that he is not quoting the saint but the words of a popular story teller, he writes

That is enough for now. I could go on, but what I have written is enough.

A fuller and more detailed exposition of this theme is found HERE.

St Seraphim of Sarov and St Francis of Assisi are patron saints of at least two modern Catholic communities, the Community of the Beatitudes in France and that of Tiberiades in Belgium. I have an icon of St Seraphim on the wall of my monastic cell. Grace crosses frontiers, uniting what was divided, including what was left out. May St Gregory of Nyssa, St Augustine, St Gregory of Nazianzen, St Francis of Assisi, St Angela de Foligno and St Seraphim of Sarov who live in a heaven without frontiers, pray for us all.

A good example of this kind of polemic writing is "A Comparison: Francis of Assisi and St. Seraphim of Sarov," from the Orthodox Christian Information Center. I shall content myself with a few quotations and commenting on them; but first I want to draw your attention to a couple of quotations from two other Catholic saints from the above two articles.

Father Raniero Cantalamessa writes about the moment one realises that one does not know God, that God is infinitely above our very capacity to know - not a theoretical knowledge you can learn from o book, but an experiential knowledge and experience of "the cloud of unknowing." He says,

However, what sort of darkness is this? It is said of the cloud that, at a certain point, interposed itself between the Egyptians and the Jews, that it was “dark for some and luminous for others” (cf. Exodus 14:20). The world of faith is dark for one who looks at it from outside, but it is luminous for one who goes inside, a special luminosity, of the heart more than of the mind. In the Dark Night of Saint John of the Cross (a variant of Gregory of Nyssa’s theme of the cloud!) the soul declares it is proceeding on its new path,

At the very moment that the person realises that God is beyond all his knowing, at that moment he becomes conscious of "a light that is more luminous than the sun at midday;" he is sharing through faith in God's knowledge of Himself.“without any other guide and light than the one that shines in my heart.” A light, however, that is “more luminous than the sun at midday.”

While St John of the Cross is talking about knowledge, St Angela de Foligno, a disciple of St Francis of Assisi, talks about this paradox of understanding and love - the doctrine is the same:

"The more you pray", she said, "the more illumined you will be and the more profoundly and intensely you will see the supreme Good, the supremely good Being; the more profoundly and intensely you see him, the more you will love him; the more you love him the more he will delight you; and the more he delights you, the better you will understand him and you will become capable of understanding him. You will then reach the fullness of light, for you will understand that you cannot understand"This paradox is missing from this Orthodox appraisal of St Francis of Assisi, and hence his picture of St Francis' progress is mistaken. His ecclesial love allows him to appreciate St Seraphim from the inside - he is on St Seraphim's wave length; but, because of the limits of his love, he sees St Francis only from the outside so that, where we see a reflection of light, he only sees the shadow of darkness.

We shall now look at the Orthodox post under discussion. Here is a quotation which shows the ignorance of the writer.

Studying the biographical data of Francis of Assisi, a fact of the utmost interest concerning the mysticism of this Roman Catholic ascetic is the appearance of stigmata on his person. Roman Catholics regard such a striking manifestation as the seal of the Holy Spirit. In Francis' case, these stigmata took on the form of the marks of Christ's passion on his body.

The stigmatisation of Francis is not an exceptional phenomenon among ascetics of the Roman Catholic world. Stigmatisation appears to be characteristic of Roman Catholic mysticism in general, both before it happened to Francis, as well as after.This is almost totally false. I am a Benedictine, and no stigmatisation appears in our monastic tradition. There has never been an English stigmatist saint. There are innumerable priest saints in the two thousand years of Catholic history, but the very first priest stigmatist to be canonised in all that time was Padre Pio who lived in the twentieth century; and he suffered much for it from the ecclesiastical authorities who regarded stigmata with the utmost suspicion. To say that stigmatism is common among Catholic saints and mystics is sheer ignorance. In fact, stigmata is more an obstacle to having sanctity recognised than universally accepted as a sign of sanctity as Padre Pio discovered , for reasons well expressed in the Orthodox article. A stigmatist is guilty until proved authentic, as St Francis and Padre Pio have been.

In fact, we see the common Tradition of the Catholic Church, we can look at the above two posts. The unusual experience of St Francis of Assisi - there were many copycat mystics after him whose sanctity was not recognised by the Church - must be interpreted in the light of that Tradition, rather than the other way round.

There comes a moment in the life of Christian mystics that is a great turning point. However hard they have tried to know God, however hard they have strived to love God, however hard they have tried to pray, they arrive at an experience of the sheer immensity of God that is, at the same time, a dark cloud and a bright light. Looking at themselves, they see that God is way beyond any possibility of our knowing him, way beyond our efforts to love him, so that, in St Angela de Foligno's words, it is an "unlove", and that in trying to pray to him we have set ourselves an impossible task. Our efforts, working in synergy with the Holy Spirit, have led us to this point. Our knowledge is ignorance, our love is unworthy of God, and our prayer has become an ineffectual tapping on a closed door. "God, my God, why have you abandoned me?"

We have all experienced this at times; but what makes this moment special is that the experience of our total inadequacy comes from our encounter with the Real Thing. God is transforming us. God's Reality is hitting us between the eyes. What is making us realise our weakness and brings us to the brink of agnosticism is not our lack of communication with the Most High, but the excess of our contact. As we realise the total inadequacy of our knowledge of God, we become aware that we are becoming participants in God's knowledge of God; as we realise that our love is totally inadequate, so we become aware of the presence within us of Christ's love for his Father which carries us, totally unworthy that we are, into the loving embrace of the Father, and are sharing Christ's love for him; as we recognise the disproportionate weakness of our prayer, an obstacle is removed, and our prayer in the Spirit wells up from the depths of our heart, uniting our prayer to Christ's own prayer. We do not live, but Christ lives in us as, in the words of St John of the Cross, “without any other guide and light than the one that shines in my heart.” A light, however, that is “more luminous than the sun at midday." This is transfiguration, what the Greeks call "theosis".

Of course, all of who participate in the Mass share in the Liturgy of heaven, and Christ celebrates the "liturgy of the heart" deep within us; and, to the degree we humbly obey as we share in the "sacrament of the present moment", the Holy Spirit unites our actions and our prayer in a certain synergy with Christ. However, as Grisha told the adolescent Prokhor who would become St Seraphim of Sarov, there is a barrier between our heart where Christ dwells and our mind, a barrier which can only be broken through, using as a tool the weapon of humble obedience. We remain spiritual schizophrenics with Christ in our heart and the world in our brain until this task is accomplished, and we can then be transfigured through and through by the divine life.

It is in this context that we must interpret the stigmata of St Francis. This is how both St Francis himself interpreted it, and how his disciple, the great theologian St Bonaventure, interpreted it. To do so, they noted the connection between Christ's death on Golgotha and his Transfiguration on Mount Tabor, Tabor illustrating the true glory of the Cross, and the Cross showing us that the light on Mount Tabor is nothing less than the divine-human self-sacrificing love of Christ.

St Bonaventure would have said the phenomenon of being transformed by light in St Seraphim and other Eastern saints and the stigmata in St Francis are different but complementary ways of manifesting theosis. Just as Christ's death and resurrection belong to one another and complement one another, so that you cannot have the crucifixion without the resurrection, and you cannot have the resurrection without the crucifixion, so you cannot have saints transformed by the light of the resurrection without their sharing in the sufferings of the Cross, and you cannot have saints manifesting their sharing in Christ's sufferings without sharing in the light of the resurrection, (though he preferred the word "fire" to "light" because the latter, for him, suggested some kind of intellectual enlightenment, while "fire" suggested intense love reaching out through intellectual darkness beyond where the intellect can go. Apart from the different forms of transfiguration in the two saints, what else was different? For St Bonaventure, who did not have such a detailed knowledge of Catholic Tradition as the Orthodox author of the article we are criticising, he regarded the stigmata of St Francis as completely and absolutely unique, a sign for the times in which they lived: God's message for the 13th century! I shall give you a reference to a much fuller treatment of this subject as the end of this post, well worth reading. For the moment, here are a couple of quotations to illustrate what I have been saying.

This is a quotation from the Fioretti which unites the theme of the stigmata and light:

And being thus inflamed in that contemplation, on that same morning he beheld a Seraph descending from heaven with six fiery and resplendent wings; and this seraph with rapid flight drew nigh unto St Francis, so that he could plainly discern him, and perceive that he bore the image of one crucified; and the wings were so disposed, that two were spread over the head, two were outstretched in flight, and the other two covered the whole body. And when St Francis beheld it, he was much afraid, and filled at once with joy and grief and wonder. He felt great joy at the gracious presence of Christ, who appeared to him thus familiarly, and looked upon him thus lovingly, but, on the other hand, beholding him thus crucified, he felt exceeding grief and compassion. He marvelled much at so stupendous and unwonted a vision, knowing well that the infirmity of the Passion accorded ill with the immortality of the seraphic spirit. And in that perplexity of mind it was revealed to him by him who thus appeared, that by divine providence this vision had been thus shown to him that he might understand that, not by martyrdom of the body, but by a consuming fire of the soul, he was to be transformed into the express image of Christ crucified in that wonderful apparition.

Then did all the Mount Alvernia appear wrapped in intense fire, which illumined all the mountains and valleys around, as it were the sun shining in his strength upon the earth, for which cause the shepherds who were watching their flocks in that country were filled with fear, as they themselves afterwards told the brethren, affirming that this light had been visible on Mount Alvernia for upwards of an hour. And because of the brightness of that light, which shone through the windows of the inn where they were tarrying, some muleteers who were travelling in Romagna arose in haste, supposing that the sun had risen, and saddled and loaded their beasts; but as they journeyed on, they saw that light disappear, and the visible sun arise.

The whole point of the contemporary fascination with these stigmata was that they were unique. For the Spirituals, he was the angel of the Apocalypse, heralding the New Age of the Holy Spirit. For St Bonaventure who did not believe in a new Age of the Spirit separate from what went before, St Francis was a living icon of Christ, a sign that God was renewing his people; but he put this renewal in the context of the ongoing action of the Holy Spirit in the Church that is the source of Tradition.

Finally, a few remarks on the quotations used in this unfortunate Orthodox article:

firstly, it is important to interpret them, not according to their meaning if Orthodox had said them, but within their proper context.

This means that they are to be interpreted according to their meaning in Catholic teaching, not Orthodox.

To do this properly, it is as important to recognise what is not said but which was too obvious to people within the context, as well as what is said.

St Francis was well known for his humility, but no mention of this is made by the Orthodox author because it would have spoiled the false picture he is constructing. In the quotations he does make, there is as much interpretation as quotation in favour of his own reading of history: it isn't trustworthy.

Nicholas Zernov had the advantage of knowing both Eastern Orthodox and Western Catholic traditions, and hence could draw a close parallel between St Seraphim and St Francis. St Ignaty Bianchaninov - I am not going to insult him like the Orthodox author of the article who called St Francis a "papist fanatic", because both were saints, the clasp of whose sandals neither he nor I are worthy to loose - was not an expert on Catholicism and, forgetting that he is not quoting the saint but the words of a popular story teller, he writes

When Francis was caught up to heaven,' says a writer of his life, 'God the Father, on seeing him, was for a moment in doubt to as [sic] to whom to give the preference, to His Son by nature or to His son by grace—Francis.' What can be more frightful or madder than this blasphemy, what can be sadder than this delusion[?]! [The Arena, Ch. 11)This is not a work of theology, but a popular story. No Catholic believes that God was in doubt in reality, and it is indicative of St Ignaty's ignorance of Catholicism to believe this to be a statement of literal belief. What can be sadder than this ignorance from a saint of God?! However, he wrote this before he went to heaven and now knows he was talking nonsense! Perhaps realising it was his purgatory. What does the passage mean when we have stripped it of its fictional content?

'God the Father, on seeing him, was for a moment in doubt to as [sic] to whom to give the preference, to His Son by nature or to His son by grace—Francis.'He believed as a Catholic that all sanctity of every saint is nothing more than a reflection of the sanctity of his Son, so that each saint and all of them together add nothing the the sanctity of Christ, but each and all participate in his sanctity by the power of his Spirit. That is Catholic teaching. I suspect that it is also Orthodox teaching. The writer is creating a little verbal drama in which St Francis is so reflecting Christ that the Father does not know which is his Son and which is his reflection: not to be taken seriously, but a way to underscore the extent to which Christ had taken over his life.

That is enough for now. I could go on, but what I have written is enough.

A fuller and more detailed exposition of this theme is found HERE.

St Seraphim of Sarov and St Francis of Assisi are patron saints of at least two modern Catholic communities, the Community of the Beatitudes in France and that of Tiberiades in Belgium. I have an icon of St Seraphim on the wall of my monastic cell. Grace crosses frontiers, uniting what was divided, including what was left out. May St Gregory of Nyssa, St Augustine, St Gregory of Nazianzen, St Francis of Assisi, St Angela de Foligno and St Seraphim of Sarov who live in a heaven without frontiers, pray for us all.

No comments:

Post a Comment