ABBOT PAUL'S HOMILY FOR GOOD FRIDAY

Good Friday 2015

“Pilate answered, “What I have written, I have written.” This was Pilate’s last stand. He had written the notice himself and fixed it to the cross; it ran: “Jesus the Nazarene, King of the Jews.” For St Paul the Cross and Christ crucified were the answer to all his questions. He needed to know nothing else and so could glory in the Cross of his Lord and Saviour, accepting all manner of suffering and hardship, a living martyrdom, in the joy and confidence of being reconciled to God in Christ Jesus.

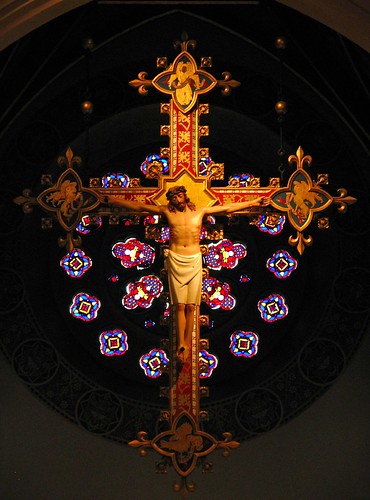

The Cross is the work of the Father, who so loved the world that he gave his only Son. It is the work of the Son, who did not cling to equality with God but humbled himself, accepting death on a cross. It is the work of the Holy Spirit, in whom the Son offers himself to the Father and who is poured out by the Son, for “bowing his head, he gave up the spirit.” In the Cross, we come to know the love of God, which passes all understanding.

Adam fell at a tree, yet by a tree he was saved. Eve was seduced at a tree, yet through a tree the bride was restored to her spouse. At a tree Satan defeated Adam: on a tree Jesus destroyed the works of the devil. At a tree God cursed man and through a tree that curse gave way to blessing. God exiled Adam from the tree of life: on a tree the New Adam endured exile that we might inherit the earth and know the joys of heaven. The Cross is the tree of knowledge, the tree of judgement and the tree of life. The Cross is the staff of Moses which divides the waters and leads us dry-shod through the sea of life. The Cross is the wood thrown into the bitter waters of Marah to make them sweet and life-giving. The Cross is the standard on which Moses lifted up the serpent in the wilderness, on which Jesus is now lifted up to draw all people to himself.

The Cross is planted on Calvary, and Golgotha is the new Eden, the new Ararat and the new Moriah. It is greater than Sinai, for the new and greater Covenant is sealed in the Blood of Christ. On the Hill of Calvary God reveals his Glory and speaks his final Word. It is greater than Mount Zion, the mountain of the Great King. It is the true Tabor, for the Transfiguration prefigured this moment when Christ is glorified and in him God is glorified and Man is deified. Calvary is the new Carmel, where the fire of God falls from heaven to consume with its living flame the twelve-stone altar of the new Israel of God, the Church, which is the Body of Christ made up of living stones. The Cross is the new ladder of Jacob, by which we climb to heaven, while Jesus is the new Bethel, the house of God, in which there are many mansions and in whom we shall live forever.

The Cross lies at the heart and at the crossroads of history, “the twisted knot at the centre of reality”, to which all previous history leads and from which all subsequent history flows. The Cross reveals the ultimate meaning of life, where the love of God embraces the whole universe and redeems it in the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, our High Priest, who takes upon his shoulders, indeed, into his very being our sufferings, our failures and our sins, the tragedy of our fallen nature. In the Letter to the Hebrews we heard. “Although he was Son, he learnt to obey through suffering, but having been made perfect, he became for all who obey him the source of eternal salvation.” The whole Bible contained in a single verse.

Pilate was a stubborn man. “What I have written, I have written,” he said. St Paul, too, was a stubborn man, calling all things so much rubbish when compared to knowing Jesus, and him crucified. In fact, he was determined to know nothing but Christ crucified, for the Jews a stumbling block, for the Gentiles sheer lunacy, but for those who believe the very wisdom and salvation of God. We need to be more stubborn in our faith, for nothing and no one can take the Cross of Jesus from us. We adore thee, O Christ, and we bless thee, for by thy Holy Cross thou hast redeemed the world. Amen.

HOMILY OF FATHER RANIERO CANTALAMESSA, O.F.M. Cap.

St. Peter's Basilica

Good Friday, 10 April 2009

“Suffering draws us into the power of the Cross”

"Christus factus est pro nobis oboediens usque ad mortem, mortem autem crucis" - "For us Christ became obedient unto death, even death on a cross". On the 2,000th anniversary of the birth of the Apostle Paul, let us listen to some of his fiery words on the mystery of Christ's death which we are celebrating. No one can help us understand its significance and importance better than he can.

His words to the Corinthians are a sort of manifesto: "For Jews demand signs and Greeks seek wisdom, but we preach Christ Crucified, a stumbling block to Jews and folly to Gentiles, but to those who are called, both Jews and Greeks, Christ the power of God and the wisdom of God" (1 Cor 1: 22-24). Christ's death bears universal importance. "One has died for all: therefore all have died" (2 Cor 5: 14). His death has given new meaning to the death of every man and every woman.

In Paul's eyes the Cross assumes cosmic significance. With it Christ knocked down the wall of separation, he reconciled men with God and with one another, destroying hatred (cf. Eph 2: 14-16). Based on this the primitive tradition was to develop the theme of the Cross as a cosmic tree that joins heaven and earth with the vertical branch and unites the different peoples of the world with the horizontal branch. It is at the same time both a cosmic and a very personal event: He "loved me and gave himself for me" (Gal 2: 20). Every human, the Apostle writes, is "one for whom Christ died" (Rom 14: 15).

From all of this arises the meaning of the Cross, no longer as a punishment, admonishment or reason for affliction but, rather, as the glory and boast of a Christian, that is, a jubilant certainty, accompanied by heartfelt gratitude, to which man rises in faith: "But far be it from me to glory except in the Cross of our Lord Jesus Christ" (Gal 6: 14). Paul has planted the Cross at the centre of the Church like the main mast at the centre of a ship. He has made it the foundation and centre of gravity of everything. He has established the permanent framework of the Christian message. The Gospels, written after him, follow his framework, making the story of Christ's Passion and death the fulcrum to which everything is oriented.

It is amazing to see all the work the Apostle carried out. It is relatively easy for us today to see things in this light, since, as Augustine said, Christ's Cross has filled the earth and now shines on the crowns of kings [1]. When Paul wrote, the Cross was still synonymous with the greatest possible dishonour, something that well-brought up people should not even mention.

The goal of the Year of St Paul is not so much to know the Apostle's thinking better (researchers are always doing this, quite apart from the fact that scientific research takes more than a year); rather, as the Holy Father has recalled on a number of occasions, it is to learn from Paul how to respond to the current challenges to the faith. One of these challenges, perhaps the most open one known yet, has become a publicity slogan plastered on public transport vehicles in London and other European cities: "There's probably no God. Now stop worrying and enjoy your life".

The most striking element about this slogan is not the premise, "God does not exist", but rather the conclusion: "Enjoy your life"! The underlying message is that faith in God is an obstacle to enjoying life, that it is an enemy of happiness. Without it there would be more happiness in the world! Paul helps us to respond to this challenge, explaining the origin and meaning of all suffering, starting with the suffering of Christ.

Why "was it... necessary that the Christ should suffer these things and enter into his glory?" (cf. Lk 24: 26) This question sometimes receives what might be termed a "weak", and in a certain sense, reassuring answer. Christ, in revealing the truth of God, necessarily provokes the opposition of the forces of evil and darkness, and these forces, as happened with the prophets, will lead to his rejection and elimination. "It was necessary that Christ suffer" would then be understood in the sense of "it was inevitable that Christ suffer".

Paul gives a very "strong" answer to that question. The need is not of the natural order but rather of the supernatural. In countries where the Christian faith has existed since antiquity the idea of suffering and the cross is almost always associated with sacrifice and expiation. Suffering, it is thought, is necessary to atone for sins and to placate God's justice. This is what has provoked, in the modern epoch, the rejection of every idea of sacrifice offered to God, and in the end, the very idea of God.

It cannot be denied that we Christians have possibly exposed ourselves to this accusation. But we are dealing with a ambiguity that a better understanding of St Paul's thought has already definitively clarified. He writes that God has preordained Christ "whom God put forward as an expiation" (Rom 3: 25). However, this expiation does not act on God to placate him, but on sin to eliminate it. "It can be said that it is God himself, not man, who expiates sin... the image is that of removing a corrosive stain or neutralizing a lethal virus rather than anger placated by punishment" [2].

Christ has given a radically new meaning to the idea of sacrifice. In it, "it is no longer man who exerts an influence on God in order to placate him. Rather it is God who acts to make man stop hating him and his neighbour. Salvation does not start with man asking for reconciliation; it begins with God's request: "Be reconciled to God" (2 Cor 5: 20ff.) [3].

The fact is that Paul takes sin seriously, he does not make light of it. For him, sin is the principal cause of man's unhappiness, the rejection of God, not God himself! Sin encloses the human creature in "lies" and "injustice" (Rom 1: 18; 3: 23), condemns the cosmic material itself to "vanity" and "corruption" (Rom 8: 19ff.) and it is also the principal cause of the social evils that afflict humanity.

Unending analyses of the economic crisis are underway in today's world and its causes, but who dares take an axe to the roots and speak about sin? The global financial and economic elite resembled a runaway train steaming recklessly ahead without brakes, without stopping to think about the rest of the train that had come to a standstill on the tracks some way back. We were heading in completely the wrong direction.

The Apostle defines insatiable avarice as "idolatry" (Col 3: 5) and points to the unbridled desire for money as "the root of all evils" (1 Tim 6: 10). Can we say he is wrong? Why are there so many families on the streets, masses of workers who have lost their jobs, if not because of some people's insatiable thirst for profit?

And why, in the recent earthquake in the Abruzzi, did so many recently built buildings collapse? What led the builders to use sea sand instead of cement?

Through his death, Christ not only denounced and conquered sin, he also gave new meaning to suffering, even to that which does not depend on anyone's sin, like the suffering of the many victims of the earthquake that recently devastated the nearby Abruzzo region. He made it a means of salvation, a path to resurrection and life. The new meaning that Christ gave to suffering was not so much made manifest in his death but rather in his victory over death, that is, the Resurrection. He "was put to death for our trespasses and raised for our justification" (Rom 4: 25): the two events are inseparable in the thought of Paul and of the Church.

It is a universal human experience: in this life pleasure and pain follow one another with the same regularity with which, when a wave swells in the ocean, a trough follows a crest and sucks in the shipwrecked sailor. "Full from the fount of Joy's delicious springs, some bitter o'er the flowers its bubbling venom springs", the pagan poet Lucretius wrote [4]. Drug use, the abuse of sex and homicidal violence all provide momentary intoxicating pleasure but lead to the person's moral dissolution and often also to his physical ruin.

Christ, with his Passion and death, inverted the relationship between pleasure and pain: "for the joy that was set before him [he] endured the Cross" (Heb 12: 2). No longer is it pleasure which ends in suffering, but suffering that leads to life and joy. It is not only a different order of events; in this way it is joy, not suffering, that has the last word, a joy that will last for eternity. "Christ being raised from the dead will never die again; death no longer has dominion over him" (Rom 6: 9). Nor will it have any power over us.

This new relationship between suffering and pleasure is reflected in the way in which time marches on in the Bible. According to human calculations, day starts with the morning and ends with the night; in the Bible day starts with night and ends with daytime: "And there was evening and there was morning, one day", says the story of creation (Gn 1: 5). It is not meaningless that Jesus died in the evening and rose in the morning. Without God, life is a day that ends in night; with God it is a night that ends in day, a day without sunset.

So Christ did not come to increase human suffering or to preach resignation to it; he came to give meaning to suffering and to announce its end and defeat. That slogan on the buses in London and in other cities may also be read by parents who have a sick child, by lonely people or the unemployed, by refugees from war zones, by people who have suffered grave injustices in life.... I try to imagine their reaction to reading the words: "There's probably no God. Now enjoy your life"! How?

Suffering is certainly a mystery for everyone, especially the suffering of the innocent, but without faith in God it becomes much more senseless. Even the last hope of redemption is taken away. Atheism is a luxury that only the privileged can afford; those who have had everything, including the possibility of dedicating themselves to study and research. This is not the only incongruity of that publicity gimmick. "God probably does not exist": so he might exist, the possibility of it cannot be totally excluded. But, dear non-believing brother or sister, if God does not exist I have not lost anything; if on the other hand he does exist, you have lost everything! We should almost thank those who promoted that advertising campaign; it has served God's cause better than so many of our apologetic arguments. It has shown up the poverty of their reasoning and helped to jolt so many sleeping consciences.

Yet God's measure of justice is different from ours and if he sees good faith or blameless ignorance he saves even those who had been anxious to fight him in their lives. We believers should prepare ourselves for surprises in this regard. "Quam multae oves foris, quam multi lupi intus!" [How many sheep are outside of the flock and how many wolves inside it!], Augustine exclaims [5].

God is capable of turning those who most persistently deny him into his most impassioned apostles. Paul is an example. What had Saul of Tarsus done to deserve that extraordinary encounter with Christ? What had he believed, hoped or suffered? What Augustine said about every divine choice can be applied to him: "Look for merit, look for justice, reflect and see whether you find anything other than grace" [6]. This is how he explains his calling: "I am the least of the Apostles, unfit to be called an Apostle, because I persecuted the Church of God. But by the grace of God I am what I am" (1 Cor 15: 9-10).

The Cross of Christ is a cause of hope for all and the Year of St Paul is an opportunity of grace also for those who do not believe and are seeking the truth. One thing speaks in their favour before God: suffering! Like the rest of humanity even atheists suffer in life and suffering, since the Son of God took it on himself, has redemptive and almost sacramental power.

In Salvifici Doloris John Paul II wrote that suffering is a channel through which the saving powers of the Cross of Christ are offered to humanity [7].

In a moment, after we are invited to pray "for those who do not believe in God", a moving prayer by the Holy Father in Latin will follow; translated it says: "Everlasting and eternal God, you have instilled in the hearts of men a deep longing for you, so that only once they find you will they have peace: grant that, overcoming every obstacle, all may recognize the signs of your goodness and, moved by the witness of our life, they may have the joy of believing in you, the one true God and Father of all mankind. Through Christ our Lord".

Notes

[1] St Augustine, Enarr. in Psalmos, 54, 12 (PL 36, 637).

[2] J. Dunn, La teologia dell’apostolo Paolo, Paideia, Brescia 1999, p. 227.

[3] G. Theissen A. Merz, Il Gesù storico. A manual, Queriniana, Brescia 2003, p. 573.

[4] Lucrezio, De rerum natura, IV, 1129 s.

[5] St Augustine, In Ioh. Evang. 45,12.

[6] St Augustine, On the Predestination of the Saints, 15, 30 (PL 44, 981).

[7] Cf. Apostolic Letter Salvifici doloris, n. 23.

GREAT AND HOLY FRIDAY

By: Father Alexander Schmemann

Friday: The Cross

From the light of Holy Thursday we enter into the darkness of Friday, the day of Christ's Passion, Death and Burial. In the early Church this day was called "Pascha of the Cross," for it is indeed the beginning of that Passover or Passage whose whole meaning will be gradually revealed to us, first, in the wonderful quiet of the Great and Blessed Sabbath, and, then, in the joy of the Resurrection day.

But, first, the Darkness. If only we could realize that on Good Friday darkness is not merely symbolical and commemorative. So often we watch the beautiful and solemn sadness of these services in the spirit of self-righteousness and self-justification. Two thousand years ago bad men killed Christ, but today we -- the good Christian people -- erect sumptuous Tombs in our Churches -- is this not the sign of our goodness? Yet, Good Friday deals not with past alone. It is the day of Sin, the day of Evil, the day on which the Church invites us to realize their awful reality and power in "this world." For Sin and Evil have not disappeared, but, on the contrary, still constitute the basic law of the world and of our life. And we who call ourselves Christians, do we not so often make ours that logic of evil which led the Jewish Sanhedrin and Pontius Pilate, the Roman soldiers and the whole crowd to hate, torture and kill Christ? On what side, with whom would we have been, had we lived in Jerusalem under Pilate? This is the question addressed to us in every word of Holy Friday services. It is, indeed, the day of this world, its real and not symbolical, condemnation and the real and not ritual, judgment on our life... It is the revelation of the true nature of the world which preferred then, and still prefers, darkness to light, evil to good, death to life. Having condemned Christ to death, "this world" has condemned itself to death and inasmuch as we accept its spirit, its sin, its betrayal of God -- we are also condemned... Such is the first and dreadfully realistic meaning of Good Friday -- a condemnation to death...

The Day of Redemption

But this day of Evil, of its ultimate manifestation and triumph, is also the day of Redemption. The death of Christ is revealed to us as the saving death for us and for our salvation.

It is a saving Death because it is the full, perfect and supreme Sacrifice. Christ gives His Death to His Father and He gives His Death to us. To His Father because, as we shall see, there is no other way to destroy death, to save men from it and it is the will of the Father that men be saved from death. To us because in very truth Christ dies instead of us. Death is the natural fruit of sin, an immanent punishment. Man chose to be alienated from God, but having no life in himself and by himself, he dies. Yet there is no sin and, therefore, no death in Christ. He accepts to die only by love for us. He wants to assume and to share our human condition to the end. He accepts the punishment of our nature, as He assumed the whole burden of human predicament. He dies because He has truly identified Himself with us, has indeed taken upon Himself the tragedy of man's life. His death is the ultimate revelation of His compassion and love. And because His dying is love, compassion and co-suffering, in His death the very nature of death is changed. From punishment it becomes the radiant act of love and forgiveness, the end of alienation and solitude. Condemnation is transformed into forgiveness...

The Destruction of Death

And, finally, His death is a saving death because it destroys the very source of death: evil. By accepting it in love, by giving Himself to His murderers and permitting their apparent victory, Christ reveals that, in reality, this victory is the total and decisive defeat of Evil. To be victorious Evil must annihilate the Good, must prove itself to be the ultimate truth about life, discredit the Good and, in one word, show its own superiority. But throughout the whole Passion it is Christ and He alone who triumphs. The Evil can do nothing against Him, for it cannot make Christ accept Evil as truth. Hypocrisy is revealed as Hypocrisy, Murder as Murder, Fear as Fear, and as Christ silently moves towards the Cross and the End, as the human tragedy reaches its climax, His triumph, His victory over the Evil, His glorification become more and more obvious. And at each step this victory is acknowledged, confessed, proclaimed -- by the wife of Pilate, by Joseph, by the crucified thief, by the centurion. And as He dies on the Cross having accepted the ultimate horror of death: absolute solitude (My God, My God, why hast Thou forsaken me!?), nothing remains but to confess that "truly this was the Son of God!..." And, thus, it is this Death, this Love, this obedience, this fullness of Life that destroy what made Death the universal destiny. "And the graves were opened..." (Matthew 27:52) Already the rays of resurrection appear.

Such is the double mystery of Holy Friday, and its services reveal it and make us participate in it. On the one hand, there is the constant emphasis on the Passion of Christ as the sin of all sins, the crime of all crimes. Throughout Orthros during which the twelve Passion readings make us follow step by step the sufferings of Christ, at the Hours (which replace the Divine Liturgy: for the interdiction to celebrate Eucharist on this day means that the sacrament of Christ's Presence does not belong to "this world" of sin and darkness, but is the sacrament of the "world to come") and finally, at Vespers, the service of Christ's burial the hymns and readings are full of solemn accusations of those, who willingly and freely decided to kill Christ, justifying this murder by their religion, their political loyalty, their practical considerations and their professional obedience.

But, on the other hand, the sacrifice of love which prepares the final victory is also present from the very beginning. From the first Gospel reading (John 13:31) which begins with the solemn announcement of Christ: "Now is the Son of Man glorified and in Him God is glorified" to the stichera at the end of Vespers -- there is the increase of light, the slow growth of hope and certitude that "death will trample down death..."

"Hell shuddered when it beheld Thee, the Redeemer of all Who was laid in a tomb. Its bonds were broken; its gates were smashed! The tombs were opened; the dead arose. Then Adam cried in joy and thanksgiving: Glory to Thy condescension, O Lover of man!”

And when, at the end of Vespers, we place in the center of the Church the image of Christ in the tomb, when this long day comes to its end, we know that we are at the end of the long history of salvation and redemption. The Seventh Day, the day of rest, the blessed Sabbath comes and with it -- the revelation of the Life-giving Tomb.

No comments:

Post a Comment