David Rutledge: Welcome to the program. This morning we're hearing from the Archbishop of Canterbury, Dr Rowan Williams - who, as well as being the Archbishop of Canterbury and head of the worldwide Anglican communion, is also a historian and theologian of considerable intellectual standing, with a special interest in the early Christian Church Fathers.

Now many of those Church Fathers were monks, living in the 4th and 5th centuries, who took off to the Egyptian desert to escape what they saw as the corruption of the church of their day. There in the desert, they tried to lead lives of prayer and meditation and stoic self-discipline; and you could hardly imagine a way of life more incongruous to those of us living in 21st century Australia.

Well, back in 2001, when he was the Archbishop of Wales, Rowan Williams was visiting Australia, and he gave a series of talks on the traditions of the Desert Fathers and their relevance to contemporary life. And this morning we're going to hear an edited version of one of those talks. It's a lecture whose title seems particularly appropriate to a time when globalisation is bringing individuals and communities from different cultures into closer and closer contact. The theme is 'Life, Death and Neighbours'.

Rowan Williams: This is a country with a desert at its heart, and that experience, perhaps yet fully to be realised and to be explored by those who lives around the edges of it. That experience is surely something which anyone attempting Christian prayer and meditation in this land must be eager to grow into.

It's very clear in the writings of the great monastics of the 4th and 5th centuries that contemplation, meditation, isn't and can never be something in itself. It is the fruit and the source of a renewed style of living together, and so 'Life, Death and Neighbours'.

I've chosen those three words, Life, Death and Neighbours, because they're words that are repeatedly interwoven in some of the recorded sayings of the first couple of generations of desert monks.

You know the essentials of the history, that in the 4th Christian century, an increasing number of Christians, worried by what they saw as the corruption or secularising of the church of their day, began to move into communities in the desert, some large, some small; many of them moved beyond that into solitude, doing so in order to rediscover what it was that the church was there for. A question whose answer wasn't always completely obvious in the 4th century, as indeed it isn't always completely obvious now.

What they discovered, what they reported back from (to borrow a familiar phrase from a fellow countryman of mine) what they discovered in the laboratory of the spirit, that was the Egyptian and the Syrian desert, has to do not only with how you pray, but how you understand your humanity. Hence: Life, Death and Neighbours, because our human life pivots around that cluster of realities for the desert monks.

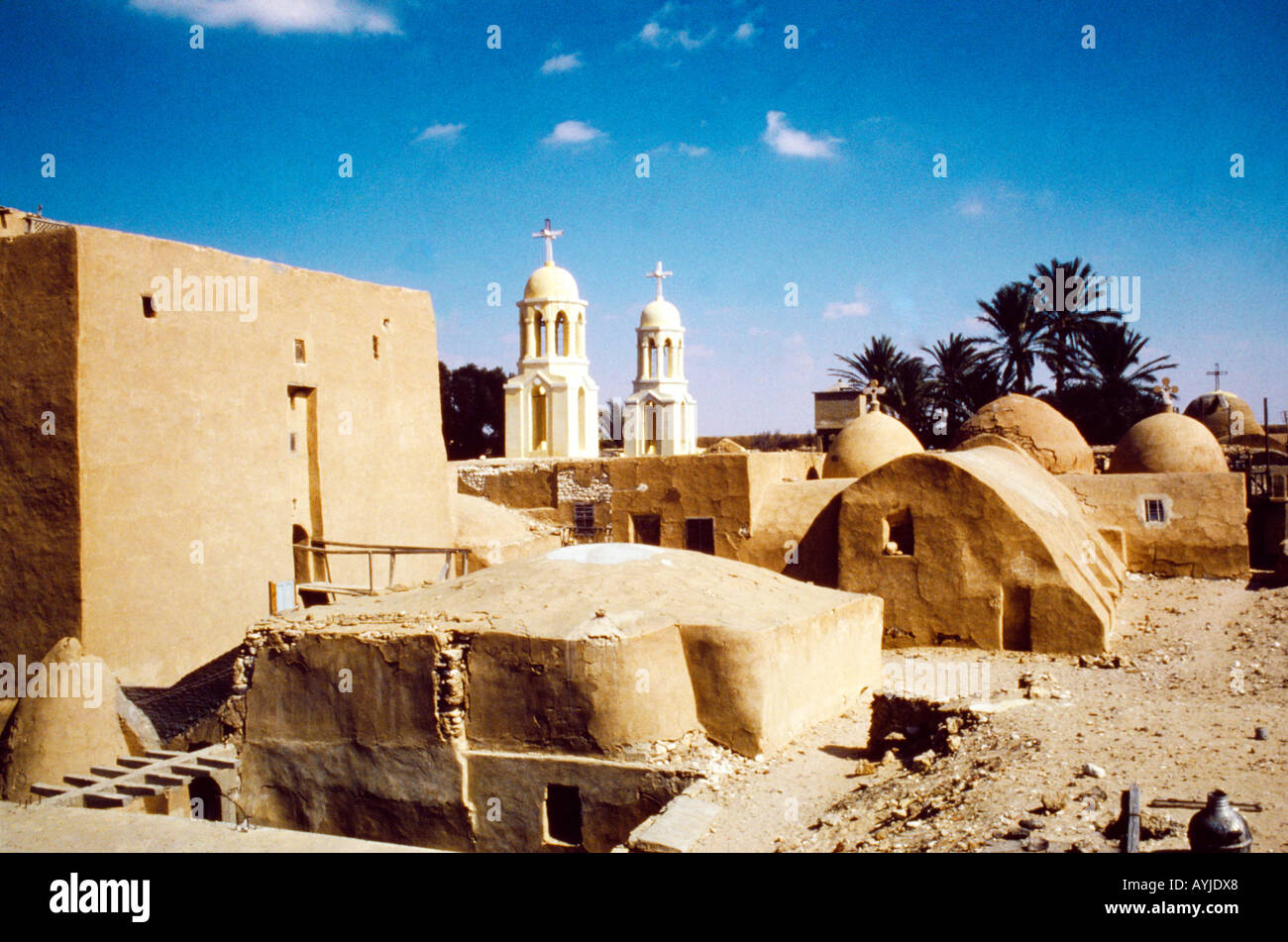

And so, some examples. You're going to hear quite a lot of quotation. In other words I'm going to let other people do the work for me. Moses the Black was an Ethiopian, a man whose personality still shines through across the millennia, and extraordinary literally larger-than-life person whose teaching and rather anarchic and unexpected example was the subject of many anecdotes and folk tales, and you will still, if you visit the monastery of Baramus in the Egyptian desert, you'll still find monks who will point across the desert to the next oasis and say 'Moses is there'.

|

| Baramus Monastery |

The sense of continuity in the Egyptian desert today incidentally, is very remarkable, and if I can be allowed just a short anecdote, I remember a visit precisely to Baramus monastery some 20 years ago, a monk slapping a pillar at the back of the church and saying, 'This is where Father Arsenius used to stand when he was alive.' And I thought, oh yes. And as the conversation proceeded, it transpired that the Father Arsenius he had in mind died in approximately 420.

Anyway, Abba Moses wrote to Abba Poemen, 'The monk must die to his neighbour and never judge him at all in any way whatever.' A brother said, 'What does it mean to think in your heart that you're a sinner?' The old man said, 'If you're occupied with your own faults, you have no time to see those of your neighbour.'

Our life and our death with our neighbour, if you gain the neighbour or the brother or sister, you gain God, you must die to your neighbour and never judge at all in any way whatever.

Gaining the neighbour - or the brother or sister - in the language that St Antony uses, seems very clearly to mean winning them for God. In a sense you might say, converting them.

Here's a story, or a saying, from Abba John the Dwarf, who said, 'You don't build a house by beginning with the roof and working down, you begin within a foundation.' They said, 'What does that mean?' He said, 'The foundation is our neighbour whom we must win. That is the place to begin. Every commandment of Christ depends on this one.'

To win, to gain the neighbour, is to put them in touch with God. In a nutshell, to put them in touch with God. And the life that is with our neighbour, the life that we gain by gaining our neighbour, the God we gain by gaining our neighbour, is that reality of putting someone else in touch with God. That, I want to suggest, is fundamental for a great deal of understanding the spirituality of the desert. And the failure to put someone in touch with God, to create an obstacle in another's path, is a kind of rebellion against Christ.

Now the desert fathers are very interested indeed in what gets in the way here, in how we put obstacles between other people and God. They were well aware that one of the major temptations of being religious is to intrude between other people and God. For many reasons, we like to think that we know more about God and they do, we like to think that it's comfortable for us to control the neighbour and their access to God, and you can read a good deal of the history of the church as a sustained attempt to police one another's relationships with God on the part of Christian people.

The desert fathers didn't escape that by going to the desert. On the contrary, in many ways, they were concerned to draw it out with greater and greater clarity, to encourage and to foster greater and greater honesty about how we get in other people's way before God. And there are a number of instances which they habitually refer to, of this kind of getting in the way. One, interestingly, is a kind of inattention to somebody else. An inattention. We think we know what they need, and that almost always arises from a failure to attend to what they really are. But that not attending to what a particular person can hear, or what a particular person can bear at any one point, that's something which recurs again and again. There are several versions of the story, in which a young monk comes to an old one in something like despair, and says, 'I have temptations, I have problems of this or that kind, and I went to Father So-and-so who said, "This is terrible, you must do 17 years penance." And I'm not sure that I can stand 17 years penance. Have you got any advice for me, Father?' And the old man almost invariably says 'Go and tell Father So-and-so...' Father So-and-so who has recommended 17 years penance has not been paying attention.

Part of that of course, relates to the concern shown by so many of the desert fathers about inappropriate kinds of harshness. Looking down on others, arising from a kind of self-confidence which is not appropriate. And it's interesting that some of the longest and fullest collections of saying, ascribed to particular fathers, gather around the names of those who are particularly remembered for being hard on harshness. Perhaps the best examples are Macarius the Great and Poemen. If Poemen really is a proper name, it simply means The Shepherd of course in Greek, and it may be that more than one person is concealed under that name. But those two, who have more sayings than almost anybody else in the collection, those two are remembered specificially for this. And of Macarius we read, unforgettably, that it was said that he became like a God in Sketes, the monastic area, because when he saw the sins of the brothers he would cast the cloak of his mercy over them. That's what God is like, that's what Macarius is like.

But there are several stories of Macarius' specific concerns, and I turn just to one of these. We see how Macarius' hardness on harshness works. He's visiting another brother called Theopemptus. And when he was alone with him, the old man asked 'How are you doing?' Theopemptus replied, 'Thanks to your prayers, fine.' The old man asked, 'Do not your fantasies war against you?' He replied, 'No, up to now, it's all right', for he was afraid to admit anything. The old man, Mascarius said to him, 'Many years I've lived as an ascetic and everybody praises me, but though I'm an old man I still have a lot of trouble with sexual fantasy.' Theopemptus said, 'Well actually Father, it's the same with me.' The old man went on admitting one after another that other thoughts warred against him until he had brought Theopemptus to admit all of them himself.

Then he said, 'How do you fast?' 'Till the ninth hour'. 'Fast a little bit longer, meditate on the gospel and the rest of the Bible. If some alien thought arises within you, don't look straight at it, but look upwards. The Lord will come to your help,' When he had given the brother this rule, the old man went back to his solitude.

Rowan Williams: Being harsh on harshness recurs in many ways, often in slightly gleeful stories of the downfall of brethren who have been excessively ascetical, and very concerned that everybody else should know that in an all-too-familiar fashion.

But turning again to Abba Poemen, a brother questioned Abba Poemen saying, 'I've committed a great sin, I feel I must do three years' penance.' The old man said, 'That's quite a lot.' The brother said, 'What about one year?' The old man said, 'That's still quite a lot.' A few other people suggested 40 days, Pomen said, 'That's a lot.' He said, 'For myself, I think if somebody repents with all his heart and does not intend to commit the sin any more, perhaps God will be satisfied with just three days.'

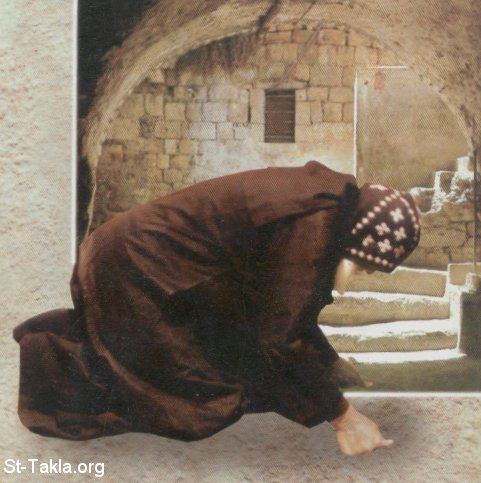

|

| Father Matta El-Meskeen 1919 - 2006 |

Harshness often comes from and goes with claims of superiority, and we've already seen how Macarius in particular turns that on its head. The gift of the spiritual director, the father, the Abba here, in gaining the neighbour, is a gift which has to do with identification. You can't say anything, you can't get anywhere unless first and foremost, the father, the director, the senior, has put himself or herself on the level of the person asking the question. Hence Macarius' wonderful therapeutic exposition of his own weakness so that the self-satisfied old monk gradually sees that it's all right to admit his.

And another story that recurs in a variety of forms is about occasions where the community at large has been eager to pass sentence and one of the great old men has countermanded it. There was a brother at Sketes who committed a fault. They called a meeting and invited Abba Moses. He refused to go, sensible man. And the priest sent someone to say to him, 'Everybody's waiting for you.' So Moses got up and went. He took a leaking jug and filled it with water and carried it with him. The others came out to meet him and said, 'What is this, Father?' The old man said to them, 'My sins run out behind me and I can't see them, and here I am coming to judge the errors of somebody else.' When they heard that, they cancelled the meeting.

The claims of superiority inherent in the eagerness to judge are again part of those obstacles we place between God and the neighbour, and therefore they stand under judgment. Repeatedly, as I say, we have a great old man like Moses, and there are others, refusing often in very dramatic ways to take part in a kind of group scapegoating. The story again is told of several people; they're invited to a council as is Moses in that story, and judgment is passed. The great old man, whoever it is, gets up and walks out. 'Where are you going father?' 'I have just been condemned.'

And you can see how all these hang together as part of one indissoluble vision of spiritual and relational therapy. Inattention to the reality of the other leads to harshness. Harshness has to do with superiority. Superiority blinds to yourself and the other. And all these failures provoke despair or mistrust, which is the worst thing you can possibly do in relation to anyone else. And that's why dying to the neighbour, is part of living with the neighbour. A monk must die to his neighbour and not judge in anything. Like Macarius, covering the sins of the brethren as if he did not see them.

It's not a kind of indifferent-ism, that sin doesn't matter; it's just that the one place you can be certain of recognising failure and alienation from God is in yourself. Hence, the advice given by Moses to Poemen, 'If you have sin enough in your own life, in your own house, there's no need to go looking for it elsewhere.' Or as another father puts it, rather more graphically, 'When you have a corpse laid out in your own front room, you don't have time to go to a neighbour's funeral.'

That curious equation with the sinner, which we've seen in Macarius' story, and which we see in many others, that is a way not of minimising the seriousness of failure, but recognising that failure is only healed by humility and solidarity, and not by condemnation. How is sin to be dealt with? It's real enough and destructive enough, and the temptation is always to say, 'I know how to deal with that - in you. Not so sure about myself, but I know how to deal with it in you'. The desert fathers are consistently saying 'You deal with it first and foremost by standing with the sinner. Whatever is the matter, you are to be there alongside them, first, last and always.'

And again, a few examples. I turn to Abba Bessarion, I think, for this one. A brother questioned Abba Poemen saying 'If I see my brother committing a sin, should I conceal it?' The old man said, 'At the moment, when we hide our brother's fault, God hides our own. At the moment when we reveal our brother's fault, God reveals our own.' Some old men came to see Abba Poemen and said to him, 'We see some of the brothers falling asleep during the divine office. Should we wake them up?' He said, 'As far as I'm concerned when I see a brother who is falling asleep during the divine office, I put his head on my knees and let him rest.' No, not indifference, but where do we start with the identification? Solidarity, that is what heals.

One last quotation from Poemen for the moment, which is about life and death with the neighbour. A brother questioned Abba Poemen saying, 'What does it mean to be angry with your brother without a cause?' He said, 'If your brother hurts you by his arrogance and you are angry with him because of it, that's getting angry without cause. If he plucks out your right eye and cuts off your right hand and you get angry with him, that's being angry without cause. But if he separates you from God, then you have every right to get angry with him.' And that puts some severe questions to a lot of what we take for granted about common life. What if the real criteria for vital common life had to do with our failure or success in connecting another person with the possibility of reconciliation or of wholeness? That, I think, is where these reflections are leading.

What if we were able to re-imagine our life together as believers in those terms? That our success (if you have to use that ridiculous and more or less useless term here) our success is to do with whether we are able to connect someone else with reconciliation and wholeness. And we connect not by successfully ordering their lives towards reconciliation and wholeness, not by triumphantly solving their problems as we would love to do, we connect by our own willingness, our own freedom to face our weakness and our faults, our own connectedness with God's mercy.

And to live like that requires obviously a pervasive critical awareness of how much in church and world we are encouraged to be competitive, to imagine success in terms of the other's loss. We gloss over that, we tidy it up and we pretend it isn't so, but as a matter of fact, in church or world, that's the model we work with.

I sometimes wonder what life in the church would be like if we had never ever developed the concept of winning and losing. In many of the great controversies that face the church at the moment, and Lord knows there are enough of those, many of those controversies it seems to me increasingly clear that nobody's going to win. In other words, there is not going to be a situation of sublime clarity in which one group's views will prevail because the other group simply says, 'Oh I see it all now.' But if we're not in the business of winning and losing like that, what does the church look like? What if we were sufficiently unafraid, (and there's a key word) sufficiently unafraid to be able to put winning and losing on the back burner, to move away from the notion that my triumph is another's loss. What if we were able to think of the health of the Christian community in terms of our ability or otherwise, our freedom or otherwise, to connect one another with the wellsprings of reconciliation. Let me go back to a phrase I used a bit earlier: 'Sin is healed by solidarity'.

The monks of the desert were looking for solitude, but not isolation. A good deal of research has been done in the last couple of decades on the importance of community to these people. And the way in which time and again in the narratives and the sayings that stem from them, time and again point is reinforced. Only in the relations they have with one another can the love and the mercy of God appear and become effective. And those mutual relations have to do with that identification, that solidarity, that willingness to stand with the accused and the condemned. And somehow it's in that action that the real healing occurs. Prayers and fasting, sleepless nights and asceticism, well various of the fathers take varying views of it. Most of them are rather sceptical about how significant that is. But if you are able in some sense, to take away what in you stands between God and the neighbour, then your own healing, as well as the other person's healing, is set forward.

So asceticism is not simply about loading your body with chains, spending 30 years on top of a pillar, sleeping two hours a night, or whatever, or even working for a merchant bank, it's about learning to contain that aspect of acquisitive human instinct that drives us constantly to compete and to ignore what's around us.

|

| modern church of the ancient monastery of St Macarius the Great |

Asceticism is a purification of seeing. It's not a self-punishment, but a way of opening the eyes. The whole of this life is about becoming instrumental to someone else's path to reconciliation. It may well be that we arrive at Heaven, if we ever do, slightly puzzled about how we got there as no doubt we all shall be, and it is explained to us that we're there quite simply because at some moment or other, we actually served another's path to reconciliation, and maybe we barely noticed it. Maybe we barely noticed it. But that's what we're there for. Our life and our death remain with our neighbour.

Our life is with our neighbour because we are alive in God when and only when, God's reconciling presence is through us, somehow connected with the reality of the neighbour. Our death is with our neighbour, because letting go of all of these things which we so love, the moral high ground, the conviction of victory, is a kind of death. But also there's a much deeper and a much nastier kind of death ahead of us if we don't deal with all that. Our life and our death are with our neighbour. If we gain the neighbour, we gain God.

Thank you.

David Rutledge: On The Religion Report you've been listening to the Archbishop of Canterbury, Rowan Williams, and an edited version of 'Life, Death and Neighbours', a lecture given in Sydney as part of the John Main Seminar.

And that's the program for this week. Thanks to technical producer Charlie McKune.

So often we aim to reach God by preaching the Gospel to others, and we dedicate most of our time to preaching. This is not the classical monastic way. When St Boniface went to Germany with a community of monks to preach the Gospel, they sought a place far away from people, a marsh called Fulda, where they could dedicate their lives to seeing God in faith. It was axiomatic for them that they could not lead others to God if they were not seeking him, following the way of humility, themselves. It was only in that context that God would grant to their words the power to bring others to Him. They would find it very puzzling that a monk would be so busy preaching that he had no time to pray because, normally, they would only be instruments of salvation to others to the extent that they opened themselves up to God: prayer wasn't something they did only when they had time: it was only prayer in humble obedience that enables them to spend their time fruitfully. God can use the words of someone who does not pray - he can use the words of a donkey, if he likes - but, without prayer and humble obedience to God's will, he is more likely to be an obstacle, for all his preaching, to God's activity. As Dr Williams shows, the monks were very much afraid of becoming obstacles, of interfering in God's own plan for the persons they met, by their attitude, by their lack of prudence, by judging others, by speaking out of turn, by their own egotism. This preaching to others within the context of their own seeking God was the way Europe was converted. (A good Lenten thought for me and for others) To the extent that I make Lent into something real, I may be laying the necessary foundation for my future apostolate.

please click on:

So often we aim to reach God by preaching the Gospel to others, and we dedicate most of our time to preaching. This is not the classical monastic way. When St Boniface went to Germany with a community of monks to preach the Gospel, they sought a place far away from people, a marsh called Fulda, where they could dedicate their lives to seeing God in faith. It was axiomatic for them that they could not lead others to God if they were not seeking him, following the way of humility, themselves. It was only in that context that God would grant to their words the power to bring others to Him. They would find it very puzzling that a monk would be so busy preaching that he had no time to pray because, normally, they would only be instruments of salvation to others to the extent that they opened themselves up to God: prayer wasn't something they did only when they had time: it was only prayer in humble obedience that enables them to spend their time fruitfully. God can use the words of someone who does not pray - he can use the words of a donkey, if he likes - but, without prayer and humble obedience to God's will, he is more likely to be an obstacle, for all his preaching, to God's activity. As Dr Williams shows, the monks were very much afraid of becoming obstacles, of interfering in God's own plan for the persons they met, by their attitude, by their lack of prudence, by judging others, by speaking out of turn, by their own egotism. This preaching to others within the context of their own seeking God was the way Europe was converted. (A good Lenten thought for me and for others) To the extent that I make Lent into something real, I may be laying the necessary foundation for my future apostolate.

please click on:

EGYPTIAN AND ETHIOPIAN MONASTICISM

|

| May these holy martyrs pray for Egypt, pray for us, for the conversion of the barbarians who killed them and for Christian Unity |

No comments:

Post a Comment