my source: Put On The Armor Of God

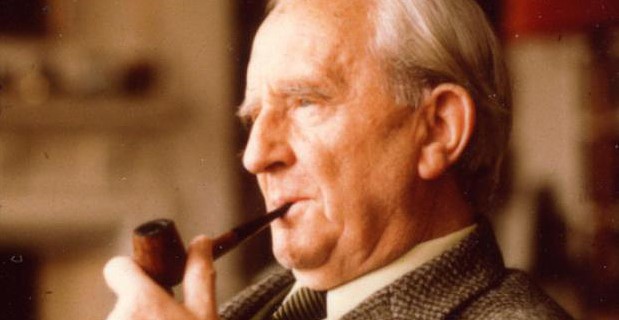

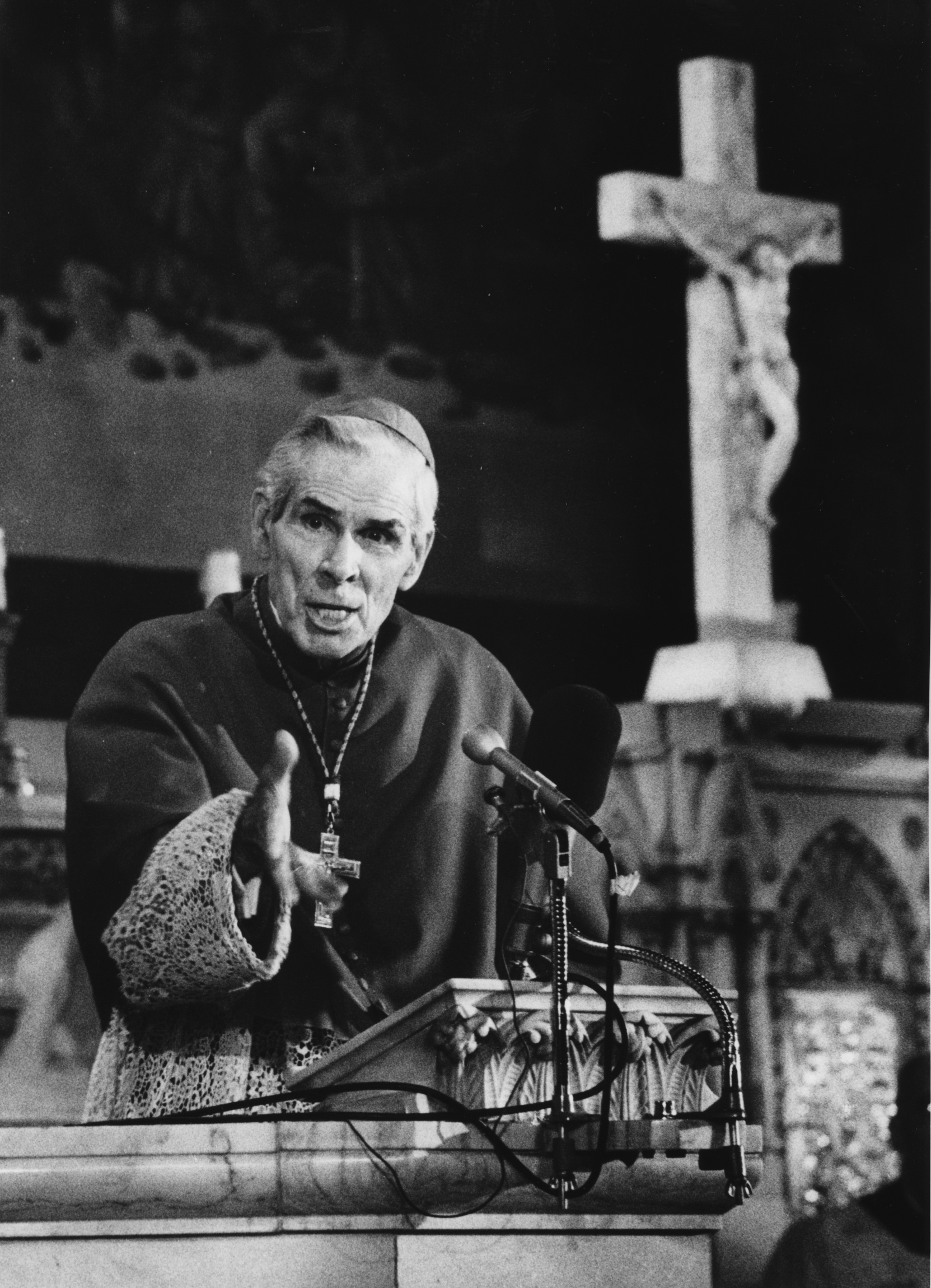

In our busy, hectic world it is a marvel that anyone gets anything done. Our days are filled to the brim and sometimes we wish we didn’t have to sleep in order to get things done. Add prayer into the mix and we barely squeak out an “Our Father” before our eyes close at the end of the day. The proposition of praying more than 5 minutes seems daunting. Yet, if we look at the lives of Mother Teresa, Fulton Sheen and J.R.R. Tolkien, we see that even the busiest people in the world were able to find time to pray not just 5 minutes, but more than a full hour.

How did they do it? Well, let’s look at each of their schedules to find out.

First, we look at Mother Teresa and the daily schedule of the Missionaries of Charity.

4:30-5:00 Rise and get cleaned up

5:00-6:30 Prayers and Mass

6:30-8:00 Breakfast and cleanup

8:00-12:30 Work for the poor

12:30-2:30 Lunch and rest

2:30-3:00 Spiritual reading and meditation

3:00-3:15 Tea break

3:15-4:30 Adoration

4:30-7:30 Work for the poor

7:30-9:00 Dinner and clean up

9:00-9:45 Night prayers

9:45 Bedtime

In particular, Mother Teresa always stressed the importance of the daily holy hour. It was a vital part of her daily schedule. She wrote:

“I make a Holy Hour each day in the presence of Jesus in the Blessed Sacrament. All my sisters of the Missionaries of Charity make a daily Holy Hour as well, because we find that through our daily Holy Hour our love for Jesus becomes more intimate, our love for each other more understanding, and our love for the poor more compassionate. Our Holy Hour is our daily family prayer where we get together and pray the Rosary before the exposed Blessed Sacrament the first half hour, and the second half hour we pray in silence. Our adoration has doubled the number of our vocations. In 1963, we were making a weekly Holy Hour together, but it was not until 1973, when we began our daily Holy Hour, that our community started to grow and blossom.”

Archbishop Fulton Sheen as well devoted himself to a daily holy hour and made sure he never missed it. He made a resolution the day of his ordination to make that a priority. He writes in Treasure in Clay,

“I resolved also to spend a continuous Holy Hour every day in the presence of our Lord in the Blessed Sacrament.”

For such a busy bishop and popular speaker as Fulton Sheen, this was not an easy task. He admits that it was hard,

“The Holy Hour. Is it difficult? Sometimes it seemed to be hard; it might mean having to forgo a social engagement, or rise an hour earlier, but on the whole it has never been a burden, only a joy……

One difficult Holy Hour I remember occurred when I took a train from Jerusalem to Cairo. The train left at four o’clock in the morning; that meant very early rising. On another occasion in Chicago, I asked permission from a pastor to go into his church to make a Holy Hour about seven o’clock one evening, for the church was locked. He then forgot that he had let me in, and I was there for about two hours trying to find a way of escape. Finally I jumped out of a small window and landed in the coal bin. This frightened the housekeeper, who finally came to my aid……

At the beginning of my priesthood I would make the Holy Hour during the day or the evening. As the years mounted and I became busier, I made the Hour early in the morning, generally before Holy Mass.

Then we have J.R.R. Tolkien. He may seem to be an odd one to include in the bunch. However, this professor, creator of the vast world of The Lord of the Rings, was also a devoted father and strong Catholic. For most of his life he worked full time as a professor and at the same time wrote the entire mythology of The Lord of the Rings in his spare time. When did he do it? When everyone else was in bed, Tolkien put more coals on the fire and went to work. He didn’t want to let his adventures in Middle Earth to infringe upon his duty as a husband and father.

He tried to strike a balance between his familial duties, deadlines at work and his desire to create a vast mythological world. Here is a peak into his daily schedule:

“It started off bright and early by biking to a nearby [Catholic Church] with his sons Michael and Christopher. Afterwards, they biked home to eat the breakfast Edith had prepared.

The morning would pass by after meeting with various pupils and lecturing at Oxford, then he would return home to have lunch with his family. Tolkien would be keenly interested in the activities of his children and made use of the time to have genuine conversations with them.

After lunch, Tolkien’s time was caught up in various meetings with dinner being short and the day ending in his study working on his latest adventure in Middle-Earth. In fact, the majority of his stories were written well into the early hours of the morning when the rest of the family members were fast asleep.” (Crisis Magazine)

And of course, there is the famous quote by Tolkien in regards to the Blessed Sacrament:

“Out of the darkness of my life, so much frustrated, I put before you the one great thing to love on earth: the Blessed Sacrament… There you will find romance, glory, honour, fidelity, and the true way of all your loves on earth.”

MY COMMENTARY

Today is the feast of Our Lord's Baptism. One question comes to mind, What kind of world do we inhabit in which water becomes the instrument by which we die and rise with Christ and in which bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ? Get the answer to that, and you will come to understand something of Catholicism. I will endeavour to answer the question, using English Catholic sources. If I am right, then this will help us to understand Catholicism everywhere because there is a consistency in the depth of all Catholicism, whatever the variety of expressions.

Catholic Spirituality, as shown in these three modern Catholics, one central European, one American and one English, is beautifully expressed in the poetry of Gerard Manley Hopkins S.J.

Summary of his life:

my source: poets.org

For this reason, Catholics spend much more time learning to be aware of his presence and to listen to him in the "sacrament of the present moment" and to abandon ourselves in humble obedience to his providence, than concentrating on miracles.

However, we really do believe in his active presence among us, just as much as the Pentecostals do: it is just that we understand our relationship with him differently: Christ does not have to intervene, make an exception to the norm, because the norm is his presence among us; the norm is that we share in his life, and he takes up residence in our churches, our communities and even in our hearts. On the same theme, G. K. Chesterton said,

That we western Catholics have experienced the presence and loving mercy of Christ through extra-liturgical devotion to the Blessed Sacrament is clear from this quotation from J.R.R. Tolkien

Of course, if all this is true, if we share in Christ's very life and mission, our chief responsibility is not to allow our auto-sufficiency to be an obstacle to Christ's action within and through us.

In this, I admire "Nightfever" because it interprets the Apostolate as simply an activity that leads people to Christ and then allows him to do his work. I remember an instruction to priest celebrants at Mass attributed to St John Chrysostom, "If Christ is to appear [as celebrant], then the priest must disappear." I believe "Nightfever" is an apostolate undertaken in the same spirit. There is only one star, the exposed Blessed Sacrament; and, unlike receiving communion, anyone can approach. It is a truly Catholic apostolate, and it works.

However, the universe is not only a sacrament of God's presence: it is a battleground. In history, there has been the constant battle between humble, courageous and costly service and the force behind the rings of power, as chronicled in "The Lord of the Rings" even in the Church itself, and even within each one of us. The more auto-sufficient we are, the further away God seems to be. To counteract the tendency to exile him to an upper storey and to live the lie that he does not exist or that he is irrelevant, we can shake things up a bit by going on a retreat or, even better sometimes, we can go on pilgrimage. In a pilgrimage, the forces of Mordor become irrelevant: the only important thing is to get there. Here is a pilgrimage in Russia from Father Stephen Freeman. It is called, "Walking in a one-storey universe."

Here Peru is the land of pilgrimage:

Finally, we may look at the Pilgrimage to the shrine of St James in Compostela which is becoming more and more popular in Western Europe. Like all main Catholic shrines, it is international, or, rather, it transcends nationality. Also, it has become ecumenical, and there are people taking part who have no religion and come for the challenge. It is the pilgrimage nearest in character to the Russian pilgrimage depicted above.

Much that I have said in my commentary is shown to be, in this last video, good, sound "Lord of the Rings" Catholicism!!

Summary of his life:

my source: poets.org

Born at Stratford, Essex, England, on July 28, 1844, Gerard Manley Hopkins is regarded as one the Victorian era’s greatest poets. He was raised in a prosperous and artistic family. He attended Balliol College, Oxford, in 1863, where he studied Classics.

In 1864, Hopkins first read John Henry Newman’s Apologia pro via sua, which discussed the author’s reasons for converting to Catholicism. Two years later, Newman himself received Hopkins into the Roman Catholic Church. Hopkins soon decided to become a priest himself, and in 1867 he entered a Jesuit novitiate near London. At that time, he vowed to “write no more...unless it were by the wish of my superiors.” Hopkins burnt all of the poetry he had written to date and would not write poems again until 1875. He spent nine years in training at various Jesuit houses throughout England. He was ordained in 1877 and for the next seven years carried his duties teaching and preaching in London, Oxford, Liverpool, Glasgow, and Stonyhurst.

In 1875, Hopkins began to write again after a German ship, the Deutschland, was wrecked during a storm at the mouth of the Thames River. Many of the passengers, including five Franciscan nuns, died. Although conventional in theme, Hopkins poem “The Wreck of the Deutschland” introduced what Hopkins called “sprung rhythm.” By not limiting the number of “slack” or unaccented syllables, Hopkins allowed for more flexibility in his lines and created new acoustic possibilities. In 1884, he became a professor of Greek at the Royal University College in Dublin. He died five years later from typhoid fever. Although his poems were never published during his lifetime, his friend poet Robert Bridges edited a volume of Hopkins’ Poems that first appeared in 1918.

Hopkins' World

Gerard Manley Hopkins' answer to my question is clear: It is the kind of world in which the Word has been made flesh, not as an afterthought, not only as a solution to the particular problem of human sin, but as the very purpose of creation, the source and flowering of its beauty, the meaning of all that exists, the reason why the world is of this kind rather than any other, the source, the means and the realisation of its fulfilment and perfection. Towards the end of his life, he wrote, ""my life is determined by the Incarnation down to most of the details of the day."

In "The Incarnational Aesthetic of Gerard Manley Hopkins," the author writes

(a)

His favourite theologian was Duns Scotus who taught that the universe was created to be united to God by means of the Incarnation. Therefore, Christ, and by necessary implication, his Mother, the Blessed Virgin, were willed by the Father at the same "moment" as he willed creation. “If God wills an end, he must will the means.” Adam and Eve are not necessary to the existence of the universe as are Christ and his Mother. We may debate and doubt the existence of Adam and Eve, but we cannot doubt the existence of Jesus and his Mother. Our existence too is not as necessary for the very existence of creation as that of Jesus and his Mother. It is on this that the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception is based.

(b)

Hopkins' World

Gerard Manley Hopkins' answer to my question is clear: It is the kind of world in which the Word has been made flesh, not as an afterthought, not only as a solution to the particular problem of human sin, but as the very purpose of creation, the source and flowering of its beauty, the meaning of all that exists, the reason why the world is of this kind rather than any other, the source, the means and the realisation of its fulfilment and perfection. Towards the end of his life, he wrote, ""my life is determined by the Incarnation down to most of the details of the day."

In "The Incarnational Aesthetic of Gerard Manley Hopkins," the author writes

(a)

Hopkins' incarnational theology pours out into his experience of nature and into the making of his art. Incarnation, the embodiment of spirit in nature, becomes the principle of Hopkins' life and Hopkins' poetry. Not merely in their explicit content and subject matter, but in their very form and material substance, his poems embody the meaning of Incarnation.

His favourite theologian was Duns Scotus who taught that the universe was created to be united to God by means of the Incarnation. Therefore, Christ, and by necessary implication, his Mother, the Blessed Virgin, were willed by the Father at the same "moment" as he willed creation. “If God wills an end, he must will the means.” Adam and Eve are not necessary to the existence of the universe as are Christ and his Mother. We may debate and doubt the existence of Adam and Eve, but we cannot doubt the existence of Jesus and his Mother. Our existence too is not as necessary for the very existence of creation as that of Jesus and his Mother. It is on this that the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception is based.

(b)

Duns Scotus hinted that Christ had a sacramental existence before the incarnation and "before Abraham was." God's first "outstress", not only within the internal procession of the Trinity but in the "barren wilderness" outside, was Christ. When Hopkins asks the purpose of God's external procession as Christ, he responds, "To give God glory...by sacrifice." Christ maximised this sacrifice by being enfleshed in the Eucharist.

Hence, for Hopkins, the going forth of Christ is at three levels: his eternal begetting by the Father within the Trinity; his presence within the whole cosmos and in all matter as the Word by which all things exist - this presence reaches its apex in the Eucharist; and the Incarnation which impresses its character on all that exists, Christ's life death and resurrection. The same Christ whom we know through the Incarnation is present in all created beings and their beauty, goodness and truth are only a reflection of his beauty, goodness and truth that lie deep down in things. The Eucharist is a window by which we are brought into contact with a presence which is eucharistic and that is everywhere and in everything, making all things sacred. The sacrifice we offer is Christ's sacrifice on the cross, a historical event, but also the human, historical expression of the Word's cosmic offering of all that exists to the Father in a dialogue of love.

This is the world we live in, a world seen through the lense provided by the Incarnation. Thus, when Hopkins visited St Winifred's Well, he wrote, "The strong unfailing flow of the water..took hold of my mind with wonder at the bounty of God in one of his saints, the sensible thing so naturally and gracefully uttering the spiritual reason of its being."

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man's smudge |&| shares man's smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod.

And for all this, nature is never spent;

There lives the dearest freshness deep down things;

And though the last lights off the black West went

Oh, morning, at the brown brink eastward, springs --

Because the Holy Ghost over the bent

World broods with warm breast |&| with ah! bright wings

For Hopkins, heaven and earth are no distance from each other, the world is charged with the grandeur of God, Christ is present everywhere and in everything. The Blessed Virgin is as close to us as the air we breath. He writes of her:

Mother, my atmosphere;My happier world, wherein To wend and meet no sin; Above me, round me lie Fronting my froward eye With sweet and scarless sky;Stir in my ears, speak there Of God’s love, O live air, Of patience, penance, prayer: World-mothering air, air wild, Wound with thee, in thee isled,Fold home, fast fold thy child.

What made him become a Catholic? While he was making up his mind he went to stay in my monastery, Belmont Abbey in Hereford; and he had a number of long talks with the Superior. In a nutshell, it was the real presence that he missed in the Church of England. Later, he wrote

My national old Egyptian reed gave way:I took of vine a cross-barred rod or rood.Then next I hungered: Love when here, they say,Or once or never took Love’s proper food;

But I must yield the chase, or rest and eat.-Peace and food cheered me where four rough ways meet.

For Gerard Manley Hopkins, the relationship between heaven and earth is intimate, an infinite God manifested in running water, brooks and sacred wells, in woods and fields, in the nourishment quality of bread and the taste of wine, in the beauty of landscape and skyscape, in great cathedrals and village chapels, present below every surface in his rejuvenating power, even where industry covers the earth with scars and human beings lose contact with nature. In the words of a fellow Jesuit, de Caussade, it is also true that "there is not a moment in which God does not present Himself under the cover of some pain to be endured, of some consolation to be enjoyed, or of some duty to be performed. All that takes place within us, around us, or through us, contains and conceals His divine action.” God is just as present and just as active where the world is running smoothly according to its own capacities as when he is working miracles. At the centre of all these myriad ways that Christ is present in us and among us is the Eucharist, which is also the centre of the cosmos and the place where heaven and earth are joined in praise..

A typical Catholic prayer that expresses the context in which we live and move and have our being is the St Patrick Breastplate:

Christ with me, Christ before me, Christ behind me, Christ in me, Christ beneath me, Christ above me, Christ on my right, Christ on my left, Christ when I lie down, Christ when I sit down, Christ when I arise, Christ in the heart of every man who thinks of me, Christ in the mouth of everyone who speaks of me, Christ in every eye that sees me, Christ in every ear that hears me.

Christ is fully God and fully man in one divine Person. Where Christ is, heaven and earth are one. All the angels and saints of heaven, all the souls of Purgatory, and all the Christians of the world are all united in him. Christ is in heaven; Christ is in his Church; and Christ is in our hearts. Can we get closer to heaven without actually dying than that?

SOME THOUGHTS ON CATHOLIC SPIRITUALITY?

We are all heirs, to a certain degree, of the Enlightenment, and many of us take it for granted that the world is a self-contained entity that functions according to its own laws, pursuing its own ends in its own ways. The Deists believed that God created the universe to act independently of him. God is external to the world, even though theists believe he can intervene.

Father Stephen Freemen, an Orthodox priest and theologian talks of Christians living in a two storey universe, with ourselves living on the ground floor, while God, the angels and saints live on the floor above. The only way God can come into our world is by intervening, by miracle, by breaking with the norm. He says that this picture goes against the Orthodox way of looking at things. I am saying that it also against the classical view of the Latin West.

Let us compare a Pentecostal service of healing with Lourdes. The Pentecostal emphasis is on miracles, on divine intervention: the more miracles, the more is Christ active among them.

There are also miracles at Lourdes, but only a small number, now and then; but we don't measure God's presence or activity by the number of miracles: God is just as active in ordinary, humdrum things, when the laws of nature are obeyed, when nothing surprising happens, but when he can make contact with us in the ordinary and the humdrum because he has entered our hearts.

Father Stephen Freemen, an Orthodox priest and theologian talks of Christians living in a two storey universe, with ourselves living on the ground floor, while God, the angels and saints live on the floor above. The only way God can come into our world is by intervening, by miracle, by breaking with the norm. He says that this picture goes against the Orthodox way of looking at things. I am saying that it also against the classical view of the Latin West.

Let us compare a Pentecostal service of healing with Lourdes. The Pentecostal emphasis is on miracles, on divine intervention: the more miracles, the more is Christ active among them.

There are also miracles at Lourdes, but only a small number, now and then; but we don't measure God's presence or activity by the number of miracles: God is just as active in ordinary, humdrum things, when the laws of nature are obeyed, when nothing surprising happens, but when he can make contact with us in the ordinary and the humdrum because he has entered our hearts.

For this reason, Catholics spend much more time learning to be aware of his presence and to listen to him in the "sacrament of the present moment" and to abandon ourselves in humble obedience to his providence, than concentrating on miracles.

However, we really do believe in his active presence among us, just as much as the Pentecostals do: it is just that we understand our relationship with him differently: Christ does not have to intervene, make an exception to the norm, because the norm is his presence among us; the norm is that we share in his life, and he takes up residence in our churches, our communities and even in our hearts. On the same theme, G. K. Chesterton said,

“If I am to answer the question, ‘How would Christ solve modern problems if He were on earth today’, I must answer it plainly; and for those of my faith there is only one answer. Christ is on earth today; alive on a thousand altars; and He does solve people’s problems exactly as He did when He was on earth in the more ordinary sense. That is, He solves the problems of the limited number of people who choose of their own free will to listen to Him.” All we have to do is learn to listen to him.

That we western Catholics have experienced the presence and loving mercy of Christ through extra-liturgical devotion to the Blessed Sacrament is clear from this quotation from J.R.R. Tolkien

“But I fell in love with the Blessed Sacrament from the beginning – and by the mercy of God never have fallen out again: but alas! I indeed did not live up to it…Out of wickedness and sloth I almost ceased to practice my religion – especially at Leeds, and at 22 Northmoor Road. Not for me the Hound of Heaven, but the never-ceasing silent appeal of Tabernacle, and the sense of starving hunger. I regret those days bitterly (and suffer for them with such patience as I can be given); most of all because I failed as a father. Now I pray for you all, unceasingly, that the Healer (the Hælend as the Saviour was usually called in Old English) shall heal my defects, and that none of you shall ever cease to cry Benedictus qui venit in nomine Domini.”I have known people - one became a monk of Belmont - who, without a strong religious background, and not knowing anything about Catholicism, have entered a church and have been gobsmacked and converted by the sense of God's presence coming from the tabernacle.

Of course, if all this is true, if we share in Christ's very life and mission, our chief responsibility is not to allow our auto-sufficiency to be an obstacle to Christ's action within and through us.

In this, I admire "Nightfever" because it interprets the Apostolate as simply an activity that leads people to Christ and then allows him to do his work. I remember an instruction to priest celebrants at Mass attributed to St John Chrysostom, "If Christ is to appear [as celebrant], then the priest must disappear." I believe "Nightfever" is an apostolate undertaken in the same spirit. There is only one star, the exposed Blessed Sacrament; and, unlike receiving communion, anyone can approach. It is a truly Catholic apostolate, and it works.

No comments:

Post a Comment