An extraordinary lesson on the liturgy, drawn from life and written by the theologian who was Joseph Ratzinger’s instructor. It’s a short text translated from the original German for the first time

by Sandro Magister

ROMA, April 12, 2006 – In Saint Peter’s basilica in Rome, Benedict XVI is celebrating his first Holy Week as pope. Meanwhile, in another ancient and grandiose basilica, that of Monreale in Sicily, the Paschal rites find a “guide” very close to him in point of view: Romano Guardini, the German theologian from whom the young Joseph Ratzinger learned the most in the area of liturgy.

The present archbishop of Monreale, Cataldo Naro, took up the original German version of Guardini’s account, translated it, and provided it for the faithful within a pastoral letter with the title “Let Us Love Our Church.” It is like a guide for today’s liturgical celebrations.

In the text, the great German theologian wrote of all his amazement at the beauty of the Monreale basilica and the splendor of its mosaics.

But above all, he wrote of how impressed he was with the faithful who attended the rites, and their “living-in-the-gaze,” with the “compenetration” of these people and the figures in the mosaics, which draw life and movement from the assembly.

“It seemed to him,” archbishop Naro notes in his pastoral letter, “that those people celebrated the liturgy in an exemplary way: through vision.”

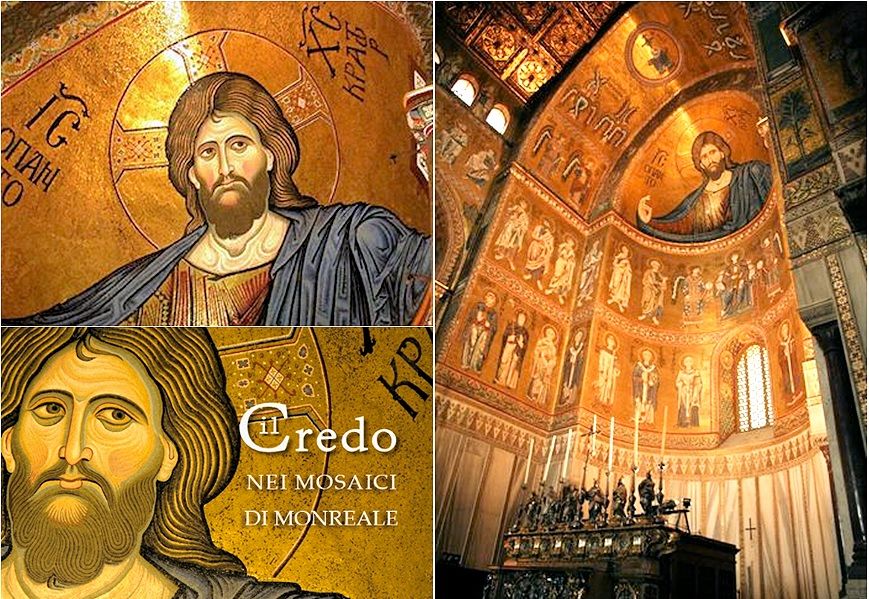

The basilica of Monreale, a masterpiece of twelfth century Norman art, has its walls completely covered with gold-enameled mosaics depicting the stories of the Old and New Testaments, angels and saints, prophets and apostles, bishops and kings, and the Christ “Pantocrator,” ruler of all, who from the apse enfolds the Christian people in his light, his gaze, his power.

Here follows a translation of Guardini’s account of his visit to Monreale, excerpted from his “Reise nach Sizilien [Voyage in Sicily]”.

The German original is in Romano Guardini, “Spiegel und Gleichnis. Bilder und Gedanken [Mirror and Parable: Images and Thoughts]”, Grünewald-Schöningh, Mainz-Paderbon, 1990, pp. 158-161.

“Then it became clear to me what the foundation of real liturgical piety is...”

by Romano Guardini

Today I saw something grandiose: Monreale. I am full of gratitude for its existence. The day was rainy. When we arrived there – it was Holy Thursday – the solemn Mass had proceeded beyond the consecration. For the blessing of the holy oils, the archbishop was seated beneath the triumphal arch of the choir. The ample space was crowded. Everywhere people were sitting in their places, silently watching.

What should I say about the splendor of this place? At first, the visitor’s glance sees a basilica of harmonious proportions. Then it perceives a movement within its structure, which is enriched with something new, a desire for transcendence that moves through it to the point of passing beyond it; but all of this culminates in that splendid luminosity.

So, a brief historical moment. It did not last long, but was supplanted by something else entirely. But this moment, although brief, was of an ineffable beauty.

There was gold all over the walls. Figures rose above figures, in all of the vaults and in all of the arches. They stood out from the golden background as though from a star-studded sky. Everywhere radiant colors were swimming in the gold.

Yet the light was attenuated. The gold slept, and all the colors slept. They could be seen there, waiting. And what their splendor would be like if it shone forth! Only here and there did a border gleam, and an aura of muted light trailed along the blue mantle of the figure of Christ in the apse.

When they brought the holy oils to the sanctuary, and the procession, accompanied by the insistent melody of an ancient hymn, wound through that throng of figures, the basilica sprang back to life.

Its forms began to move. Responding to the solemn procession and the movement of vestments and colors along the walls and through the arches, the spaces began to move. The spaces came forward to meet the listening ear and the eye rapt in contemplation.

The crowd sat and watched. The women were wearing veils. The colors of their garments and shawls were waiting for the sun to make them shine again. The men’s faces were distinguished and handsome. Almost no one was reading. All were living in the gaze, all engaged in contemplation.

Then it it became clear to me what the foundation of real liturgical piety is: the capacity to find the “sacred” within the image and its dynamism.

* * *

Monreale, Holy Saturday. When we arrived, the sacred ceremony had come to the blessing of the Paschal candle. Immediately afterward, the deacon solemnly advanced along the principal nave, bearing the Lumen Christi.

The Exultet was sung in front of the main altar. The bishop was seated to the right of the altar, on an elevated throne made of stone, where he sat listening. After the Exultet came the readings from the prophets, and I rediscovered the sublime significance of those mosaic images.

Then there was the blessing of the baptismal water in the middle of the church. All the assistants were seated around the font, with the bishop in the center and the people standing around them. The babies were brought forward – one could see the emotion and pride in their parents – and the bishop baptized them.

Everything was so familiar. The people’s conduct was simultaneously detached and devout, and when anyone spoke to another person standing nearby, it was not a disturbance. And so the sacred ceremony continued on its way. It moved through almost every part of that great church: now it took place in the choir, now in the nave, now under the triumphal arch. The spaciousness and majesty of the place embraced every movement and every figure, commingling them and uniting them together.

Every now and then a ray of sunlight pierced through the vault, and a golden smile spread across the space above. And anywhere a subdued color lay in wait on a vestment or veil, it was reawakened by the gold that spread to every corner, revealed in its true power and caught up in an harmonious and intricate design that filled the heart with happiness.

The most beautiful thing was the people. The women with their veils, the men with their cloaks around their shoulders. Everywhere could be seen distinguished faces and a serene bearing. Almost no one was reading, almost no one stooped over in private prayer. Everyone was watching.

The sacred ceremony lasted for more than four hours, but the participation was always lively. There are different means of prayerful participation. One is realized by listening, speaking, gesturing. But the other takes place through watching. The first way is a good one, and we northern Europeans know no other. But we have lost something that was still there at Monreale: the capacity for living-in-the-gaze, for resting in the act of seeing, for welcoming the sacred in the form and event, by contemplating them.

I was about to leave, when suddenly I found all of those eyes turned toward me. Almost frightened, I looked away, as if I were embarrassed at peering into those eyes that had been gazing upon the altar.

In the life of the Church, there is a primary “mythic” experience: the Liturgy. Liturgical action is more than an antiquated manner for having a Church meeting. It is the ritual, sacramental and symbolic enactment of a Reality that might otherwise not be seen, understood, or experienced. That same reality, presented in a non-mythic manner, would be less accessible and probably misunderstood. Tolkien was right: we must become mythopathic.

The attraction of Lewis’ and Tokien’s writings are witness to the fact that there is a deep mythopathic part even in the modern heart. This is not a modern phenomenon - it is a human phenomenon. It is the anti-mythic character of modern culture that sets it apart from all human cultures that have come before. The reduction of the world to a narrow, materialist understanding of fact, is simply a world unable to communicate God

.

An excerpt from "Glory to God for All Things" by Fr Stephen Freeman, an Orthodox priest in America. The post is called, "The Struggle to be Real"

In the life of the Church, there is a primary “mythic” experience: the Liturgy. Liturgical action is more than an antiquated manner for having a Church meeting. It is the ritual, sacramental and symbolic enactment of a Reality that might otherwise not be seen, understood, or experienced. That same reality, presented in a non-mythic manner, would be less accessible and probably misunderstood. Tolkien was right: we must become mythopathic.

The attraction of Lewis’ and Tokien’s writings are witness to the fact that there is a deep mythopathic part even in the modern heart. This is not a modern phenomenon - it is a human phenomenon. It is the anti-mythic character of modern culture that sets it apart from all human cultures that have come before. The reduction of the world to a narrow, materialist understanding of fact, is simply a world unable to communicate God

.

No comments:

Post a Comment