“Men of Galilee, why do you stand looking up to heaven? This Jesus who has been taken up from you into heaven shall come in the same way as you have seen Him going up to heaven.”

Acts 1:11

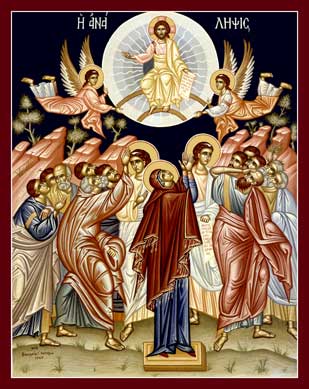

Today we celebrate the Solemnity of the Ascension today as mandated by Bishops Conference for Dioceses England and Wales. Thus we raise our thoughts to heaven where, as we see in today’s Epistle (Acts 1:1-11), Our Lord Jesus has ascended.Pope St. Leo the Great said: “Christ’s Ascension is our ascension; our body has the hope of one day being where its glorious Head has preceded it.” This is what Jesus said on the night before He died: “I go to prepare a place for you, and if I shall go and prepare a place for you, I will come again and will take you to myself; that where I am you also may be.” Jn. 14: 23. According to Fr. Gabriel, OCD in his book of meditations, Divine Intimacy, “The Ascension is then, a feast of joyful hope, a sweet foretaste of heaven. By going before us, Jesus our Head has given us the right to follow Him there some day, and we can even say with St. Leo, ‘In the person of Christ, we have penetrated the heights of heaven.’ (Roman Breviary) As in Christ Crucified, we die to sin; as in the Risen Christ, we rise to the life of grace, so too, we are raised up to heaven in the Ascension of Christ. This vital participation in Christ’s mysteries is the essential consequence of our incorporation in Him. He is our Head; we, as His members, are totally dependent upon him and intimately bound to His destiny. ‘God, who is rich in mercy,’ says St. Paul, ‘for His exceeding charity wherewith He loved us…hath quickened us together in Christ… and hast raised us up… and hath made us sit together in the heavenly place through Christ Jesus.’ Eph. 2:4-6 Our right to heaven has been given us, our place is ready; it is for us to live in such a way that we may occupy it someday.” Fr. Gabriel, “Divine Intimacy,” p. 535

“…ascending on high, He hath led captivity captive.” Ps. 67:19

In today’s Mass, the Alleluia verses give us a powerful prophecy of the Messias leading souls into heaven: “Alleluia. The Lord is in Sinai, in the holy place; ascending on high, He hath led captivity captive.” Ps. 67:19 This image of captives being led into the city of their conquerors was common in Rome when victorious generals would lead their conquests, as their trophies, into the imperial city. So, too, Jesus will lead those whom He has redeemed into heaven as Dom Prosper Gueranger in The Liturgical Year, Vol.9 explains: “The two Alleluia-versicles give us the words of the royal psalmist, wherein he celebrates the glorious Ascension of the future Messias, the acclamation of the angels, the loud music of heaven’s trumpets, the gorgeous pageant of the countless fortunate captives of limbo whom the conqueror leads up, as His trophy, to heaven.” Gueranger, p. 179. How blessed shall we be who are led into heaven as trophies of Christ’s glorious redemption.

“Sweet Sorrow of Christ’s Ascension”

Although Jesus’ Ascension into Heaven has an element of sorrow, Jesus told us that our “sorrow will be turned to joy.” (Jn. 16:20) We can see this especially if we look at Jesus’ Ascension through the eyes of His beloved Mother Mary. The disciples of Jesus used to wonder which of the two sentiments, sadness or joy, had priorityin Our Lady’s heart when Jesus ascended into heaven. Dom Prosper Gueranger comments on this question: “They (disciples) used to ask themselves, which of the two sentiments was uppermost in her maternal heart, –sadness, that she was to see her Jesus no more, or joy, that He was now going to enter into the glory He so infinitely deserved. The answer was soon found: had not Jesus said to His disciples: ‘If ye loved Me, ye would indeed be glad, because I go to the Father’; Jn. 14:28 Now, who loved Jesus as Mary did? The Mother’s heart, then, was full of joy at parting with Him. How was she to think of herself, when there was question of the triumph of her Son and her God? Could she that had witnessed the scene of Calvary, do less than desire to see Him glorified, whom she knew to be the sovereign Lord of all things, — Him whom, but a short time ago, she had seen rejected by His people, blasphemed, and dying the most ignominious and cruel of deaths?” Gueranger, p. 170

“Sorrow to turn to joy!”

“Amen, Amen I say to you that your shall weep and lament, but the world shall rejoice; and you shall be sorrowful but your sorrow shall be turned to joy.” Jn. 16:20

But before our sorrow turns to joy in heaven with Jesus’ return, the angels remind the disciples that they must not stand idle. They are to return to Jerusalem and await the Holy Spirit. Then the disciples are instructed to go into the whole world and baptize all in the name of the Father, Son and Holy Spirit: “Go, therefore, and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you: and behold I am with you all days, even to consummation of the world.” Mt. 28:19-20 Jesus gave His disciples this commission just before He ascended into heaven. Dom Gueranger tells us that thedisciples were still caught up in the moment of Jesus’ Ascension: “The disciples are still steadfastly looking up to towards heaven, when lo! two angels, clad in white robes, appear to them saying: ‘Ye men of Galilee! Why stand ye looking up to heaven? This Jesus, who is taken up from you into heaven, shall so come as ye have seen Him going into heaven!’ Acts 1:10-11

Joy and Triumph in the Ascension

Dom Gueranger again reminds us of the meaning of Jesus’ Ascension: “He has ascended, a Saviour; He is to return a Judge: between these two events is comprised the whole life of the Church on earth. We are therefore living under the reign of Jesus as our Saviour, for He has said: ‘God sent not His Son into the world to judge the world, but that the world might be saved by Him:’ (Jn. 3:17) and to carry out this merciful design He has been giving to His disciples the mission to go throughout the whole world, and invite men, while yet there is time, to accept the mystery of salvation. …. They love Jesus; they rejoice at the thought of His having entered into His rest. ‘They went back into Jerusalem with great joy.’ Lk. 24:52 These few simple words of the Gospel indicate the spirit of this admirable feast of the Ascension: it is a festival which, not withstanding its soft tinge of sadness, is, more than any other expressive of joy and triumph.” Gueranger, p. 173-4 After his Ascension, the Apostles, as seen in today’s gospel (Mark 16:14-20), had been commissioned the Apostles to preach the gospel to the whole world: “And He said to them: ‘Go ye into the whole world and teach the gospel to every creature. He that believeth and is baptized shall be saved: but he that believeth not shall be condemned.” Mk. 16: 15-16 In Jerusalem, the Apostles’ joy had to await the coming of the Holy Spirit who would fill them with His power at Pentecost to preach the gospel to all nations. How joyful we too should be to have the “good news” of the gospel given to our Apostolic Church'

my source: Pay Attention To The Sky

When a verb is turned into a noun, the subject is usually the one who commits the action: A wrestler is one who wrestles, a builder is one who builds, and a plumber is one who plumbs. So also, I would like to primarily call by the name “liturgist” the one who commits liturgy, and only secondarily (as it is more commonly used) the one who studies it or directs it.

If, as will be made clear below, liturgy names an action, then we ought to be directed to the ones who do that action. Liturgists make up the Church, andthe Church is made up of liturgists, and the word liturgist can be used as virtually synonymous with baptized or with laity to name the members of the mystical body of Christ.

The roots of this viewpoint are in the doctrine of creation. It is a doctrine that places man and woman, as microcosm, at the interface between the spiritual realm and the material realm. Louis Bouyer pictures it in this way:

Therefore, this cosmological priesthood in the structure of the world should not be confused with either the Church’s common priesthood of the laity, or the Church’s ministerial priesthood of the ordained. The latter two are for the healing of the first. The common priesthood of the laity is directed toward the cure of this now corrupted structure of the world, and the ministerial priesthood is at the service of the common priesthood to equip them for their lay apostolate.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church seems to be describing the liturgical job description of the baptized when it says,

Liturgical theology is derivative from the liturgists’ encounter with God. Liturgical theology materializes upon the encounter with the Holy One, not upon the secondary analysis at the desk. God shapes the community in liturgical encounter, and the community makes theological adjustment to this encounter, which settles into ritual form. Only then can the analyst begin dusting the ritual for God’s fingerprints.

These methodological assertions affect the arena where we can expect liturgy to operate, as well as the density of our concept of liturgy. Two uses of the term liturgical must be accounted for, and I shall suggest one be called thin, the other thick. Paul Holmer has said, “Liturgy is not an expression of how people see things; rather it proposes, instead, how God sees all people.” I propose that liturgy in its thin sense is an expression of how we see God; liturgy in its thick sense is the expression of how God sees us.

Temple decorum and ritual protocol is liturgy only in its thin sense; in its thick sense, liturgy is theological and ascetical. Both senses are true and necessary, and one way of constructing the question would be to ask how thick liturgy is expressed in its ritual form (thin). I take this thicker meaning, residing behind the rubrics, to be what Alexander Schmemann means when he identifies the proper object of liturgical theology:

The Church can modify the liturgy, but only in its thin sense. In its thick sense, it is liturgy that creates the Church: a theological corporation, Kavanagh said, and practitioners of asceticism. It is my overarching objective to keep this thicker liturgical grammar before the face of liturgical studies curricula.

Failing this, liturgy is relegated in divinity schools to practical “how to” courses for ecclesiastics who get a thrill out of rubrical tidiness, and in the academy at large it is relegated to departments of history or anthropology or comparative ritual, if it is studied at all.

Sometimes it is treated as a branch of spirituality, i.e., the doxological titillation of the otherwise stolid theological mind. Sometimes it is handled as a branch of history, and as historians might treat the creeds or papal documents they might likewise investigate an obscure medieval psalter. Sometimes it is subsumed under a branch of systematics, usually sacramentology, but also under various “theologies of. . .” worship, prayer, doxology, and so forth.

And finally, and increasingly in vogue, liturgy is made into a branch of ritual studies that attempts an uncritical report of the worship protocols practiced by any given community. These branches of academic study are inadequate to fully comprehend liturgy because, as Taft bluntly says, “Liturgy, therefore, is theology. It is not history or cultural anthropology or archeology or literary criticism or esthetics or philology or pastoral care.“

Liturgy (whose grammar we are trying to discover in its amplitude) had a larger meaning when Christians borrowed it in the first place. Leitourgia was “the usual designation for a service performed by an individual for the state (often free of charge).”

“In classical Greek, liturgy (leitourgia) had a secular meaning; it denoted a work (ergon) undertaken on behalf of the people (laos).Public projects undertaken by an individual for the good of the community in such areas as education, entertainment or defense would be leitourgia. The word became especially appropriate to name religious cult, that complex of actions that surrounded public services done in the name of the city, “because they were linked to its most vital interests. In a culture permeated by religious values (as most of the traditional cultures were), ‘liturgy’ thus understood was predicated first and foremost of actions expressing the city’s relations to the world of divine powers on which it acknowledged itself to be dependent.” The mark of liturgy was its reference to the organized community. A work, then, done by an individual or a group was a liturgy on behalf of the larger community to which he, she, or they belonged. As Schmemann puts it:

That means there is something wrong with thinking liturgy is the work of the clergy on behalf of the laity (clericalism), or with thinking that liturgy is not valid unless everyone has a share in the work of the ministerial priesthood (laicism). In fact, liturgy is the work of Christ on behalf of the vital interests of the clan to which he belongs: the family of Adam and Eve. Christ is the premier liturgist, head of a body animated by the Holy Spirit, and so it is Christ’s work that the Church performs — which is to say the thick liturgy done by the Church must always and only be Christ’s liturgy, never its own.

The sacramental power of baptism creates the people of God (laos) and commissions them to perform Christ’s work (ergon). That’s where liturgists come from: They are regenerated. Christ is the firstborn of many little liturgists who perpetuate a Christic, kenotic, salutary, sacerdotal, prophetic, and royal work.

The liturgy is therefore our product and not our work at all. It is why the presiding celebrant is said to be an alter Christus. Romano Guardini saw the difference between the Eucharistic memorial and other types of memorial in the fact that Jesus did not say, “On a certain day of the year you are to come together and share a meal in friendship….” Such an act would issue from the humanly possible, Guardini says, and only the event it was celebrating would be divine.

Christ spoke differently. His “do these things” implies “things I have just done”; yet what He did surpasses human possibility. It is an act of God springing as incomprehensibly from His love and omnipotence as the acts of Creation or the Incarnation. And such an act He entrusts to men!

He does not say: “Pray God to do thus,” but simply “do.” Thus he places in human hands an act which can be fulfilled only by the divine … God determined, proclaimed, and instituted; man is to execute the act. When he does so, God makes of it something of which He alone is capable.

my source: Pay Attention To The Sky

The Ascension of Christ by Dosso Dossi,

One way to enlarge our grammar of liturgy (see previous post on Liturgy as grammar) might be to change our use of the word liturgist. I do not use it in either of two conventional ways. Ordinarily, a liturgist is thought to be either the person who might want to read (or even write) a book like this one, or else the person who remembers to order the branches for Palm Sunday. That is, the person we ordinarily call “liturgist” is the one who conducts classes, or conducts choirs. But this does overlook one very significant person.When a verb is turned into a noun, the subject is usually the one who commits the action: A wrestler is one who wrestles, a builder is one who builds, and a plumber is one who plumbs. So also, I would like to primarily call by the name “liturgist” the one who commits liturgy, and only secondarily (as it is more commonly used) the one who studies it or directs it.

If, as will be made clear below, liturgy names an action, then we ought to be directed to the ones who do that action. Liturgists make up the Church, andthe Church is made up of liturgists, and the word liturgist can be used as virtually synonymous with baptized or with laity to name the members of the mystical body of Christ.

The roots of this viewpoint are in the doctrine of creation. It is a doctrine that places man and woman, as microcosm, at the interface between the spiritual realm and the material realm. Louis Bouyer pictures it in this way:

The tradition of the Fathers has never admitted the existence of a material world apart from a larger creation, from a spiritual universe. To speak more precisely, for them the world, a whole and a unity inseparably matter and spirit…. Across this continuous chain of creation, in which the triune fellowship of the divine persons has, as it were, extended and propagated itself, moves the ebb and flow of the creatingAgape and of the created eucharistia. Descending further and further towards the final limits of the abyss of nothingness, the creating love of God reveals its full power in the response it evokes, in the joy of gratitude in which, from the very dawn of their existence creatures freely return to him who has given them all. Thus this immense choir of which we have spoken, basing ourselves on the Fathers, finally seems like an infinitely generous heart, beating with an unceasing diastole and systole, first diffusing the divine glory in paternal love, then continually gathering it up again to its immutable source in filial love.”Man and woman were created as rational liturgists of the material world and placed at the apex of the systolic action in order to translate the praise of mute matter into speech and symbol. I am interested in rediscovering an understanding of this cosmological priesthood by seeing Christ’s priesthood as the eschatological recapitulation of Adam and Eve’s dignity. The fall was the forfeiture of our liturgical career. The economy of God, climaxing in Christ’s paschal mystery, was the means to restore it.

Therefore, this cosmological priesthood in the structure of the world should not be confused with either the Church’s common priesthood of the laity, or the Church’s ministerial priesthood of the ordained. The latter two are for the healing of the first. The common priesthood of the laity is directed toward the cure of this now corrupted structure of the world, and the ministerial priesthood is at the service of the common priesthood to equip them for their lay apostolate.

The Catechism of the Catholic Church seems to be describing the liturgical job description of the baptized when it says,

“The whole community of believers is, as such, priestly since the faithful exercise their baptismal priesthood through their participation, each according to his own vocation, in Christ’s mission as priest, prophet, and king.”In order to equip and capacitate this common priesthood of his body, Christ instituted the ministerial priesthood, which is “directed at the unfolding of the baptismal grace of all Christians. The ministerial priesthood is a means by which Christ unceasingly builds up and leads his Church.” The clergy alone is not Church, with lay spectators; and the laity alone is not Church, with hired ordained leaders. Therefore, “though they differ from one another in essence and not only in degree, the common priesthood of the faithful and the ministerial or hierarchical priesthood are nonetheless interrelated: each of them in its own special way is a participation in the one priesthood of Christ.”

Liturgical theology is derivative from the liturgists’ encounter with God. Liturgical theology materializes upon the encounter with the Holy One, not upon the secondary analysis at the desk. God shapes the community in liturgical encounter, and the community makes theological adjustment to this encounter, which settles into ritual form. Only then can the analyst begin dusting the ritual for God’s fingerprints.

These methodological assertions affect the arena where we can expect liturgy to operate, as well as the density of our concept of liturgy. Two uses of the term liturgical must be accounted for, and I shall suggest one be called thin, the other thick. Paul Holmer has said, “Liturgy is not an expression of how people see things; rather it proposes, instead, how God sees all people.” I propose that liturgy in its thin sense is an expression of how we see God; liturgy in its thick sense is the expression of how God sees us.

Temple decorum and ritual protocol is liturgy only in its thin sense; in its thick sense, liturgy is theological and ascetical. Both senses are true and necessary, and one way of constructing the question would be to ask how thick liturgy is expressed in its ritual form (thin). I take this thicker meaning, residing behind the rubrics, to be what Alexander Schmemann means when he identifies the proper object of liturgical theology:

To find the Ordo behind the “rubrics,” regulations and rules — to find the unchanging principle, the living norm or “logos” of worship as a whole, within what is accidental and temporary: this is the primary task which faces those who regard liturgical theology not as the collecting of accidental and arbitrary explanations of services but as the systematic study of the lex orandi of the Church. This is nothing but the search for or identification of that element of the Typicon which is presupposed by its whole content, rather than contained by it…A problem arises, however, when we limit ourselves to speaking only about the thin sense. In that case, it’s hard to imagine liturgical theology meaning anything more than devotional affectation, and “it’s hard to imagine liturgical asceticism meaning anything more than the songbooks monks used. Liturgy is more than rubric, like music is more than score. Just as the word music can name either the notes or the act of making music, so the word liturgy (thin) can name the ritual score or a supernatural dynamic (thick).

The Church can modify the liturgy, but only in its thin sense. In its thick sense, it is liturgy that creates the Church: a theological corporation, Kavanagh said, and practitioners of asceticism. It is my overarching objective to keep this thicker liturgical grammar before the face of liturgical studies curricula.

Failing this, liturgy is relegated in divinity schools to practical “how to” courses for ecclesiastics who get a thrill out of rubrical tidiness, and in the academy at large it is relegated to departments of history or anthropology or comparative ritual, if it is studied at all.

Sometimes it is treated as a branch of spirituality, i.e., the doxological titillation of the otherwise stolid theological mind. Sometimes it is handled as a branch of history, and as historians might treat the creeds or papal documents they might likewise investigate an obscure medieval psalter. Sometimes it is subsumed under a branch of systematics, usually sacramentology, but also under various “theologies of. . .” worship, prayer, doxology, and so forth.

And finally, and increasingly in vogue, liturgy is made into a branch of ritual studies that attempts an uncritical report of the worship protocols practiced by any given community. These branches of academic study are inadequate to fully comprehend liturgy because, as Taft bluntly says, “Liturgy, therefore, is theology. It is not history or cultural anthropology or archeology or literary criticism or esthetics or philology or pastoral care.“

Liturgy (whose grammar we are trying to discover in its amplitude) had a larger meaning when Christians borrowed it in the first place. Leitourgia was “the usual designation for a service performed by an individual for the state (often free of charge).”

“In classical Greek, liturgy (leitourgia) had a secular meaning; it denoted a work (ergon) undertaken on behalf of the people (laos).Public projects undertaken by an individual for the good of the community in such areas as education, entertainment or defense would be leitourgia. The word became especially appropriate to name religious cult, that complex of actions that surrounded public services done in the name of the city, “because they were linked to its most vital interests. In a culture permeated by religious values (as most of the traditional cultures were), ‘liturgy’ thus understood was predicated first and foremost of actions expressing the city’s relations to the world of divine powers on which it acknowledged itself to be dependent.” The mark of liturgy was its reference to the organized community. A work, then, done by an individual or a group was a liturgy on behalf of the larger community to which he, she, or they belonged. As Schmemann puts it:

It meant an action by which a group of people become something corporately which they had not been as a mere collection of individuals — a whole greater than the sum of its parts. It meant also a function or “ministry” of a man or of a group on behalf of and in the interest of the whole community. Thus the leitourgia of ancient Israel was the corporate work of a chosen few to prepare the world for the coming of the Messiah…. Thus the Church itself is a leitourgia, a ministry, a calling to act in this world after the fashion of Christ, to bear testimony to him and His kingdom.

Liturgy was an act of largesse; it required magnanimity; it was not a domestic act for one’s kith and kin, but a public act for the community in which one dwelled.

That means there is something wrong with thinking liturgy is the work of the clergy on behalf of the laity (clericalism), or with thinking that liturgy is not valid unless everyone has a share in the work of the ministerial priesthood (laicism). In fact, liturgy is the work of Christ on behalf of the vital interests of the clan to which he belongs: the family of Adam and Eve. Christ is the premier liturgist, head of a body animated by the Holy Spirit, and so it is Christ’s work that the Church performs — which is to say the thick liturgy done by the Church must always and only be Christ’s liturgy, never its own.

The sacramental power of baptism creates the people of God (laos) and commissions them to perform Christ’s work (ergon). That’s where liturgists come from: They are regenerated. Christ is the firstborn of many little liturgists who perpetuate a Christic, kenotic, salutary, sacerdotal, prophetic, and royal work.

The liturgy is therefore our product and not our work at all. It is why the presiding celebrant is said to be an alter Christus. Romano Guardini saw the difference between the Eucharistic memorial and other types of memorial in the fact that Jesus did not say, “On a certain day of the year you are to come together and share a meal in friendship….” Such an act would issue from the humanly possible, Guardini says, and only the event it was celebrating would be divine.

Christ spoke differently. His “do these things” implies “things I have just done”; yet what He did surpasses human possibility. It is an act of God springing as incomprehensibly from His love and omnipotence as the acts of Creation or the Incarnation. And such an act He entrusts to men!

He does not say: “Pray God to do thus,” but simply “do.” Thus he places in human hands an act which can be fulfilled only by the divine … God determined, proclaimed, and instituted; man is to execute the act. When he does so, God makes of it something of which He alone is capable.

THE ASCENSION OF THE LORD IN ORTHODOXY

by Archpriest Victor Potapov

Throughout the 40 days following the Feast of the Resurrection of Christ, Paschal chants sound within our churches and in the hearts of the faithful. The Risen Christ spent that period of time on earth, demonstrating to His disciples the reality of His Resurrection. But lo, that 40-day period draws to a close, and, the “leave-taking,” as it were, of the Feast of Pascha approaches. In the vocabulary of the Church, the day of leave-taking is known as the Apodosis of Pascha. The service for the Apodosis of Pascha is celebrated in the brilliant white of Paschal vestments, illuminated by the light of the Paschal sun, with that same fullness of joy as on the first day of Pascha. And the Feast of the Ascension approaches: That day enters our lives as a spiritual reality: the day on which the Apostles and the Mother of God gathered around the Risen Savior for the last time, on the Mount of Olives; the day on which, while blessing them, He began his departure from the earth, and as St. Luke the Apostle tells us in the Acts of the Apostles, “and a cloud received Him out of their sight.”

Ordinary human consciousness, drawing only on the experience of earthly existence and its physical laws, can no more comprehend Christ’s Ascension than it could His Incarnation or His Glorious Resurrection from the dead. Even the disciples who saw the empty Tomb, who saw the Risen Christ, who witnessed His Ascension, had mixed feelings about everything they had seen. They vacillated between exaltation over the miracles they had witnessed and misunderstanding and doubt. Toward the end of the Gospel according to Matthew, we read that the 11 Disciples saw the Risen One in Galilee, “and when they saw Him, they worshipped Him: but some doubted.” The laconic words of the Gospel say nothing about the nature of their doubts. But the Apostles’ doubt makes their state close to that feeling familiar to anyone striving to find a conscious and faith grounded in understanding.

The true, religious order, beyond wisdom, reveals itself to us in response to our effort to touch it, but only with the assistance of the grace of God, which heals the infirmities and fills what is growing scant. Only with the miracle of Pentecost, the descent of the Holy Spirit upon the Apostles that took place 10 days after the Savior’s Ascension, were the Apostles completely freed from their doubts. We see them as fearless and untiring witnesses to, and preachers of, the Word, fearless even in the face of persecution and martyrdom. From a human perspective, they could have been expected to mourn upon their being parted from the Lord. Yet, in the Gospels it says that they returned to Jerusalem with joy.

Why did Christ, the Miracle Worker Who had conquered death, not remain on earth to lead and rule over His people? The reply is found in the Gospel according to John, which records for us Christ’s talk with His disciples before His Passion, and His High-priestly prayer to His Father. In speaking to his disciples about his coming departure from them, he had in mind not only His Passion and death on the Cross, but His Ascension to Heaven that was to follow. As long as Christ was still on earth, the work of the salvation of man and all creation had not been accomplished. For Christ came so that those who are on earth might be united to the heavens and that end of that podvig, which is for us unto salvation, is His Ascension. In it our human existence, having gone through the crucible of suffering, and shown that it is more powerful than death, is brought into the fullness of divine life: In His Ascension, Christ did not become dis-embodied, dis-Incarnate. He remains forever, perfect God and perfect Man. By His earthly path in obedience to that Truth He had revealed to us, we can unite our life with His perfect and eternal existence, and thereby enter into the Kingdom of Glory which He revealed to us.

In His Ascension, Christ left the world different from what it was when the miracle of His entry into the world, His birth of the Most-pure Virgin Mary, took place. Most of the human race then remained in darkness, and only individual select prophets lived in hope and anticipation of the coming of the Savior and Messiah into the world. Now it was a different world, and a new people of God. That earth had witnessed the miracle of the birth in Bethlehem, had seen Christ’s Transfiguration, and had been illumined by the light of His Resurrection from the dead. It was for that reason that Christ ascended, blessing that earth which He was leaving for a time, but from which He was henceforth to be eternally inseparable. Parting from Christ at His Ascension is at the same time a joyous anticipation of His victorious Second Coming.

No comments:

Post a Comment