The Press divided those taking part in the Second Vatican Council into “Conservatives” and “Progressives”. Of course it was an over-simplification; but it was handy and suited their journalistic purpose. In fact, among those who wanted to change things, (the “Progressives”), there were at least two tendencies that had distinct goals, though this was not so apparent at the time. Both wanted decentralization of the Church in order to give more importance and autonomy to the local Church; both thought that the teaching of Vatican I needed to be balanced by an emphasis on collegiality and the function of the local bishop; both wanted a reform of the liturgy; and both were ecumenically orientated. They often spoke the same language and voted the same way in the Council; but their goals and their theological positions were irreconcilable as they stood, and this has only become apparent to the Church at large since the Council.

Firstly, there were the liberals, often Anglo-Saxon, who wanted more decision-making at local and individual levels, and hence less directives from the centre. Like the conservatives who saw the Church as a perfect society, they thought of the Church in political and legal terms, even though, like them, they accepted that this political entity is the body of Christ. The doctrine of the body of Christ served to justify and sanctify their basically political view of the Church, just as it justified and sanctified the legalistic view of the conservatives. Like the conservatives, they thought that the solutions to the Church’s problems were about jurisdiction and law, but, unlike the conservatives, they advocated a contemporary liberal political model which gave more freedom for the individual to make decisions and take initiatives, a certain level of democracy in the Church, and a far greater tolerance of dissent. Generally, but not always, they accepted papal dogma as a law of belief that was binding on them, but they interpreted it so that that the pope could only pass such a law in very restricted circumstances; and they believed that everything not defined in an “infallible decree” could be freely doubted or disbelieved or changed. They wanted to leave as much as possible up to the individual to make up his own mind. In things biblical, they considered the methods used in modern scholarship to be the surest way to understand Scripture. In things theological, they insisted on academic freedom for theologians and denied the right of the Vatican or any other ecclesiastical authority to question, criticize or, still less, to condemn their conclusions..

In things ecumenical, they looked to the Anglican Church as a natural partner, though wanting more coherence than the Anglican Communion has. They saw the Second Vatican Council as the Catholic equivalent to the Protestant Reformation; and, in its popular version, liked to contrast “post-Vatican Ii” with “pre-Vatican II”, where “pre-Vatican II” is everything that is conservative and bad, and “post-Vatican II” is all that is progressive and good.. Funnily enough, because they have a basically political vision, they are much closer in their understanding of the Church to the conservative camp who they oppose at every turn than they are to the second group who voted with them in the Cyouncil. Later, they would see the problem of women priests in political terms, as part of the fight for equal rights for women, and would consider it an open question because there is no dogma against women clergy, and the Scriptural argument is inconclusive. Scripture can be interpreted in the light of the feminist agenda rather than by Tradition because women priests is basically a political problem.

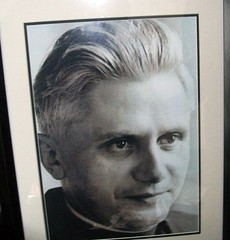

This other group were often patristic scholars and liturgists like Ratzinger and Bouyer; and they saw the Church, not in political terms, but primarily as a sacramental organism, and believed that the authority of popes and even of general councils is limited and the ties between a bishop and his flock are assured by this very fact.

The juridical ties that bind a bishop to his flock only give external shape to much deeper ties that are the fruit of the Holy Spirit acting through the liturgy. The Pope, although he has universal episcopal jurisdiction over the whole Church, cannot act as though these deeper ties do not exist. To do so would be to deny the Source of his own relationship with the Church. His universal jurisdiction is the servant of the true Source of Catholic unity which is the Holy Spirit acting through the liturgy and manifesting his Presence in ecclesial love. The pope is servant of Catholicity world-wide which is called communion, and he is servant of Catholicity in time, down the ages, from the time of the Apostles to the present day, which is called Tradition. This group wanted to see the liturgy reformed to express the sacramental nature of the whole Church rather than as an expression of powers given to priests as individuals at their ordination; they believed that “Tradition” is an ongoing process in which the Church acts in harmony with the Holy Spirit and is an absolutely central dimension of the Catholic Reality;

and their ecumenical gaze fell on the Orthodox and other Eastern Churches as their natural partners. As the Holy Spirit was present and active in the Church before and during the Council, and would be present after the Council, because it is the presence of the Holy Spirit that makes the Catholic Church what it is, any changes would have to be consistent with the unity of the Church across time and space. For them Vatican II could not be a “Catholic Reformation” in the Protestant mould, because the Holy Spirit is constantly acting in “synergy” with the Church which is thus a divine – human reality, the body of Christ. What the Spirit does together with the Church in one generation cannot be overthrown in the next. Clearly Fr Joseph Ratzinger has not changed his theology. This is how he saw it at the time:

The juridical ties that bind a bishop to his flock only give external shape to much deeper ties that are the fruit of the Holy Spirit acting through the liturgy. The Pope, although he has universal episcopal jurisdiction over the whole Church, cannot act as though these deeper ties do not exist. To do so would be to deny the Source of his own relationship with the Church. His universal jurisdiction is the servant of the true Source of Catholic unity which is the Holy Spirit acting through the liturgy and manifesting his Presence in ecclesial love. The pope is servant of Catholicity world-wide which is called communion, and he is servant of Catholicity in time, down the ages, from the time of the Apostles to the present day, which is called Tradition. This group wanted to see the liturgy reformed to express the sacramental nature of the whole Church rather than as an expression of powers given to priests as individuals at their ordination; they believed that “Tradition” is an ongoing process in which the Church acts in harmony with the Holy Spirit and is an absolutely central dimension of the Catholic Reality;

and their ecumenical gaze fell on the Orthodox and other Eastern Churches as their natural partners. As the Holy Spirit was present and active in the Church before and during the Council, and would be present after the Council, because it is the presence of the Holy Spirit that makes the Catholic Church what it is, any changes would have to be consistent with the unity of the Church across time and space. For them Vatican II could not be a “Catholic Reformation” in the Protestant mould, because the Holy Spirit is constantly acting in “synergy” with the Church which is thus a divine – human reality, the body of Christ. What the Spirit does together with the Church in one generation cannot be overthrown in the next. Clearly Fr Joseph Ratzinger has not changed his theology. This is how he saw it at the time:

“The decision to begin with the liturgy schema was not merely a technically correct move. Its significance went far deeper. This decision was a profession of faith in what is truly central to the Church–the ever-renewed marriage of the Church with her Lord, actualized in the eucharistic mystery where the Church, participating in the sacrifice of Jesus Christ, fulfils its innermost mission, the adoration of the triune God. Beyond all the superficially more important issues, there was here a profession of faith in the true source of the Church’s life, and the proper point of departure for all renewal. The text did not restrict itself to mere changes in individual rubrics, but was inspired from this profound perspective of faith. The text implied an entire ecclesiology and thus anticipated … the main theme of the entire Council – its teaching on the Church. Thus the Church was freed from the ‘hierarchological’ (Congar) narrowness’ of the last hundred years, and returned to its sacramental origins” (14). Theological Highlights of Vatican II (New York: Paulist Press/Deus Books, 1966)

The ‘hierarchological’ narrowness was the ‘conservative idea of the Church as held together by a hierarchic system with the pope at the top. In its place, the Church was returning “to its sacramental origins”, without, of course, denying its hierarchic structure. Little did he know that many who voted the same way as he did were advocating another form of “narrowness”, equally political, but cast in a liberal democratic mould.

There is no doubt that Vatican II endorsed Ratzinger’s position. The great change of perspective and emphasis is contained in this key sentence in the Constitution on the Liturgy: the liturgy is “the summit toward which the activity of the Church is directed; at the same time it is the fountain from which all her power flows.” ((Const. Lit. I. 10). The Catechism of the Catholic Church spells out the meaning of this all important sentence+

1104Christian liturgy not only recalls the events that saved us but actualizes them, makes them present. The Paschal Mystery is celebrated, not repeated. It is the celebrations that are repeated, and in each celebration there is an outpouring of the Holy Spirit that makes the unique mystery present.

1105 The Epiclesis (invocation upon) is the intercession in which the priest begs the Father to send the Holy Spirit …

1106 Together with the anamnesis the epiclesis is at the heart of every sacramental celebration, most especially of the Eucharist…

1107 The Holy Spirit’s transforming power in the liturgy hastens the coming of the kingdom….

1108 In every liturgical action the Holy Spirit is sent in order to bring us into communion with Christ and so to form his body. …The most intimate cooperation of the Holy Spirit and the Church is achieved in the liturgy. The Spirit, who is the Spirit of communion, abides indefectibly in the Church. For this reason the Church is the great sacrament of divine communion which gathers God’s scattered children together. Communion with the Holy Trinity and fraternal communion are inseparably the fruit of the Spirit in the liturgy. (my emphasis).

The liturgy is “the source of all the Church’s powers” because “the most intimate cooperation of the Holy Spirit is achieved in the liturgy” That the Church is the sacrament of communion in the life of the Blessed Trinity and of the human race is “inseparably the fruit of the liturgy”. Hence the Church is not infallible because the pope and general council are infallible: it is the other way round. The liturgy is the source of their ability to exercise that authority because it is the vehicle of “the most intimate cooperation of the Holy Spirit and the Church” without which the infallibility of popes and general councils would be impossible. The liturgy is also the summit towards which dogmatic pronouncements are directed because it is only when the dogmatic teaching is integrated into our worship that it is fully functioning as a dogma.

Hence, on specific occasions, pope and council are infallible with the infallibility of the Church, an infallibility which springs from its liturgical life, where the synergy between the Holy Spirit and the life of the Church is at its most intense. The theologians of this group would have agreed with the Armenian Orthodox theologian Vardapet Karekin Sarkissian who wrote, “Faith or doctrine is not truth on paper, or formulae in creeds and conciliar decrees or canons, but something living, faith lived or doctrine professed in the permanent experience of the Church’s life as a whole; in other words “Orthodoxia”.” (“Orthodoxy” is, at one and the same time “true doctrine” and “true worship”, really meaning "true glory". Because the Church is "orthodox", it manifests the "true glory" of God as Christ did on the Cross. In other words, Orthodoxy finds its fullest expression in the liturgy where it is a part of worship, not in the decrees of councils or popes, however infallible they may be when they define doctrine; the orthodoxy of dogmatic definitions is ordered towards true worship, and in this way gives glory to God.)

When Pope John Paul II was asked to permit women to be bishops, he did not answer that he was against women bishops. He said that he had no authority or power to permit women bishops. He declared in Sacerdotio Ordinatio : “Wherefore, in order that all doubt may be removed regarding a matter of great importance, a matter which pertains to the Church's divine constitution itself, in virtue of my ministry of confirming the brethren (cf. LK 22:32) I declare that the Church has no authority whatsoever to confer priestly ordination on women and that this judgment is to be definitively held by all the Church's faithful” (no. 4) Others want to abolish the old rite of saying Mass and celebrating the sacraments.. Cardinal Ratzinger said wrote:

From my own personal point of view I should like to give further particular emphasis to some of the criteria for liturgical renewal thus briefly indicated. I will begin with those last two main criteria.

It seems to me most important that the Catechism, in mentioning the limitation of the powers of the supreme authority in the Church with regard to reform, recalls to mind what is the essence of the primacy as outlined by the First and Second Vatican Councils: The pope is not an absolute monarch whose will is law, but is the guardian of the authentic Tradition, and thereby the premier guarantor of obedience. He cannot do as he likes, and is thereby able to oppose those people who for their part want to do what has come into their head. His rule is not that of arbitrary power, but that of obedience in faith. That is why, with respect to the Liturgy, he has the task of a gardener, not that of a technician who builds new machines and throws the old ones on the junk-pile. The "rite", that form of celebration and prayer which has ripened in the faith and the life of the Church, is a condensed form of living tradition in which the sphere which uses that rite expresses the whole of its faith and its prayer, and thus at the same time the fellowship of generations one with another becomes something we can experience, fellowship with the people who pray before us and after us. Thus the rite is something of benefit which is given to the Church, a living form of paradosis -- the handing-on of tradition." (His review of The Organic Development of the Liturgy by Dom Alcuin Reid OSB of Farnborough Abbey.

"Therefore, with the greatest feeling, great understanding for the preoccupations and fears, in union with those responsible, one should understand that this missal is also a missal of the Church, under the authority of the Church; that it is not something of the past to be protected, but a living reality of the Church, much respected in its identity and in its historical greatness. All the liturgy of the Church is always a living thing, a reality which is above us, not subject to our wills or arbitrary wishes." ((from a speech at Fongombault in July 2001)

For Ratzinger no one has the authority to invent and propose for use a completely new rite. All the rites in use except for the Armenian Rite have their origins in the three patriarchal sees of Apostolic Foundation, Rome, Antioch and Alexandria, and even the Armenian rite belongs to a Church that was evangelized in Apostolic times. Hence all Catholic rites are products of Apostolic Tradition which it is the function of pope and bishops to protect and serve, not to replace or abolish. They are not free to cut the Church loose from these rites or to make arbitrary changes. On the contrary, they are fulfilling the purpose of their authority when they use it to protect and make them more accessible. He wrote:

"The Christian faith can never be separated from the soil of sacred events, from the choice made by God, who wanted to speak to us, to become man, to die and rise again, in a particular place and at a particular time. . . . The Church does not pray in some kind of mythical omnitemporality. She cannot forsake her roots. She recognizes the true utterance of God precisely in the concreteness of its history, in time and place: to these God ties us, and by these we are all tied together. The diachronic aspect, praying with the Fathers and the apostles, is part of what we mean by rite, but it also includes a local aspect, extending from Jerusalem to Antioch, Rome, Alexandria, and Constantinople. Rites are not, therefore, just the products of inculturation, however much they may have incorporated elements from different cultures. They are forms of the apostolic Tradition and of its unfolding in the great places of the Tradition." (163/4 The Spirit of the Liturgy)

The 2nd Vatican Council is also an event within this Tradition. This means that the post-conciliar liturgy must be interpreted in the light of the Tradition of which it is a relatively new expression. It also means that the pope does not have the power simply to abolish a form of liturgy that has been the norm for many hundreds of years,n nor to abolish the new rite, however much he may prefer the old..; The pope is the guardian of Tradition,not its master. To use Cardinal Ratzinger’s metaphor, the pope is like a gardener who has to respect the laws of botany, not a mechanic who can construct what he likes as long as it works. He has written:

"After the Second Vatican Council, the impression arose that the pope really could do anything in liturgical matters, especially if he were acting on the mandate of an ecumenical council. Eventually, the idea of the givenness of the liturgy, the fact that one cannot do with it what one will, faded from the public consciousness of the West. In fact, the First Vatican Council had in no way defined the pope as an absolute monarch. On the contrary, it presented him as the guarantor of obedience to the revealed Word. The pope's authority is bound to the Tradition of faith, and that also applies to the liturgy. It is not "manufactured" by the authorities. Even the pope can only be a humble servant of its lawful development and abiding integrity and identity. . . . The authority of the pope is not unlimited; it is at the service of Sacred Tradition."(165/6 The Spirit of the Liturgy)

The Church is a sacramental organism, a living process that develops according to its own inherent laws; and these have to be respected by whoever is in charge, just as much as by those who obey him. The Church is not a mechanism nor is its basic structure the product of mere legislation. Therefore, those in charge of the Church on earth cannot simply re-construct it at will using their legal authority. The Church, far from being the “perfect society” of the conservatives or the “liberal society” of the progressives, is the most imperfect of human societies because it can only function by the power of the Spirit who is outside its control. It needs and has a proper juridical system, but this system is at the service of the Spirit who requires the obedience of faith, both from those who legislate and enforce and from those who obey. Jurisdiction has no power over Tradition and must always act within it. I believe that this is the reason why the Pope did not consult the bishops when he gave general permission for the use of the old Latin rite: he believed that the attempt to block its use was as beyond his and their authority as it is beyond the authority of the Anglican Synod to introduce into the Church female bishops and priests.

The Anglican Synod claims more authority than the pope, but no more authority than those that want the Vatican to abolish outright the old Mass. For both Anglicans and Catholic liberal progressives, law and not Tradition has the last word. For the Catholic Church of Ratzinger, as well as for the Orthodox and Oriental Orthodox churches, Tradition and not law has the last word. To pass the measure on women bishops through synod the Anglicans show that they have a ‘lower’ doctrine of the relationship between the structure of the Church and of Tradition. It is not enough to say as the Archbishop of Canterbury did, that there is nothing in Scripture strong enough to impede the introduction of women bishops and priests. In a Catholic view of Tradition, the understanding that the Church has gained down the ages of a particular biblical text and the implications the Church has drawn from that reading form part of any full exegisis of that text, even if scholars tell us that this is not the original meaning. Texts can grow in meaning and may come to express different meanings which reverent prayer can turn into a coherent whole.. In Catholicism the Bible does not stand alone apart from Tradition, because the Holy Spirit is involved in both, which means they belong together. The continual exposure of the Church to the Bible through the liturgy, in which things old and new are understood with the help of the same Spirit who is Author of the Bible, is a constituant dimension of Tradition.

Has it ever occurred to you that those who wish the Church authorities to completely abolish the old Latin Roman rite and to permit women bishops share the same presuppositions as those who want the pope to declare the Blessed Virgin “Mediatrix of All Graces”?

Those who wish the pope to make the teaching on Mary a dogma believe that law is above liturgy. It is not enough for them that Our Lady’s holiness and position in God’s plan of Salvation are expressed in prayers, prefaces and offices of the Catholic liturgy. They hold that an official papal proclamation of Mary’s privileges gives more glory to God and to Our Lady than the liturgy does. Law is above liturgy in their estimation of things, even in giving glory to God. They are not sufficiently aware of the synergy between the Spirit and the Church which is the basic reality of the liturgy and makes it the supreme, highest expression of the Catholic faith; though, in times of crisis it may be necessary to proclaim or emphasize anew a dogma of pope or council in order to preserve the unity of the Church or in order to interpret the liturgy aright when this becomes a matter of dispute.. However, the liturgical expression of a truth is a good deal closer to the reality it is expressing than is a proclaimed dogma. It is the function of dogmatic pronouncements to expound and defend Catholic orthodoxy so that the liturgy can more faithfully give glory to God.

Like those who want a new dogma, the reformers believe that the pope’s signature is all that is needed to change a sacramental practice of two thousand years. For them law is above liturgy. Similarily, the Anglicans believe that it lies within the competence of their Synod to introduce women priests and bishops. Both Catholic reformers and Anglicans underestimate the importance of the organic nature of the Church’s Tradition and exaggerate the power of jurisdiction in its relationship to liturgy. They forget that it is from the celebration of the liturgy that all the Church’s power flows, not the other way round..

In contrast, the Anglican Book of Common Prayer is the classic example of a rite which is the product of a victory of law over liturgy, as well as over the Tradition which the liturgy expresses; so, in accepting women bishops and priests, the Anglican Church is only being consistent with its past. In contrast, the "ordinariates" aim to re-integrate Anglicanism into the Roman Rite from which they were untimely ripped at the Reformation.

In contrast, the Anglican Book of Common Prayer is the classic example of a rite which is the product of a victory of law over liturgy, as well as over the Tradition which the liturgy expresses; so, in accepting women bishops and priests, the Anglican Church is only being consistent with its past. In contrast, the "ordinariates" aim to re-integrate Anglicanism into the Roman Rite from which they were untimely ripped at the Reformation.

It is because of these principals that the Pope Benedict XVI restored the old Latin Mass by removing the prohibitions that were de facto imposed on its use. He justifies this move by an appeal to Tradition:

"It is good to recall here what Cardinal Newman observed, that the Church, throughout her history, has never abolished nor forbidden orthodox liturgical forms, which would be quite alien to the Spirit of the Church. An orthodox liturgy, that is to say, one which expresses the true faith, is never a compilation made according to the pragmatic criteria of different ceremonies, handled in a positivist and arbitrary way, one way today and another way tomorrow.

The orthodox forms of a rite are living realities, born out of the dialogue of love between the Church and her Lord. They are expressions of the life of the Church, in which are distilled the faith, the prayer and the very life of whole generations, and which make incarnate in specific forms both the action of God and the response of man." .

However, there is still much work to be done, both by persuading the Latin Mass people that the “new Mass” is fully Catholic, a new expression of the age-old Catholic Tradition, and by persuading the advocates of the “new Mass” that the very nature of the liturgy imposes on the Pope the obligation, not only to permit, but to support the “old Mass”, not against the “new Mass” but in favour of those for whom the old Latin Mass is the normal means by which they participate in the Christian Mystery. Judging by the bitterness that is shown, both on the internet and on the ground, and by the opinions expressed by even very knowledgeable people who have the good of the Church at heart on both sides of the debate, we have a long way to go; but contact in charity is the only way forward. As in the wider ecumenical scene, faith is knowledge born of religious love. Where there is no love, no proper understanding of each other can be sustained. The basis of understanding is the same, both within the Catholic Church and in our relations with traditions external to her: it is love which illuminates our faith, and which drives us on to embrace and comprehend expressions of the same faith that are beyond but not incompatible with our own

No comments:

Post a Comment