The Kavasilas Option

by

Fr. Micah Hirschy

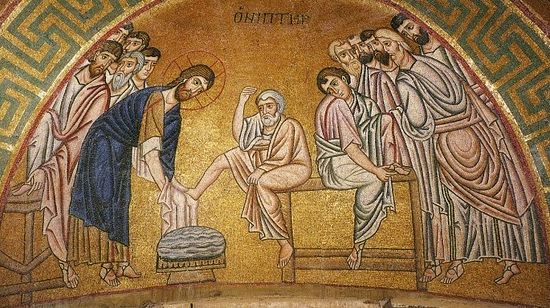

St. Nicholas Kavasilas

Much has been written in the last couple of years concerning the “Benedict Option.” People have found inspiration in it as well as a great deal to criticize about both the movement and Rod Dreher’s book. The historicity and theology of the book are questionable. The dire picture painted is difficult not to dismiss when every Orthodox Church echoes with Christ is Risen from the dead, by death trampling down death. However, what is perhaps needed is not another criticism or debate about the “Benedict Option.” Instead, the time has come to explore another “Option.” This Option is rooted in the Gospel and found in the 2nd-century letter to Diognetus as well as the novels of Dostoyevsky. In contemporary times, it has been incarnated by a diversity of people that include Mother Maria Skobtsova and St. Porphyrios. This is the Kavasilas Option.

St. Nicholas Kavasilas lived during the 14th century in the twilight of what has become known as the Byzantine Empire. The empire was besieged on the outside by the Muslims to the East and the Latins to the West. Within the empire were turmoil, civil wars, and uprisings. Religious controversies touched nearly every aspect of society. Nicholas was in the middle of it all. He was a scientist and theologian. He was a close friend to St. Gregory Palamas and was an advisor to emperors. He counted among his friends both Hesychasts and humanists. St. Nicholas wrote about the Liturgy and the Mysteries while contemporary scholarship is all but certain he remained a layman his entire life. Far from removing himself from society, there does not seem to be any area of society and culture with which he was not fully engaged.

The Kavasilas Option begins with the Liturgy. St. Nicholas was quite clear in saying that everything needed is given in the Liturgy; a person can add nothing to what Christ has given in the sacred Mysteries. At the same time, it is necessary and depends on the person to preserve what has been given. St. Nicholas believed that this was done by reflecting on Christ and meditating upon the Law of the Spirit which is love. Olivier Clement puts it quite succinctly when he writes that Kavasilas

“recommends brief meditations to those living in his day, reminders in a way to remember, within the time it takes to put one foot in front of the other, that God exists and that He loves us” (Three Prayers, 32).

Here there is no self-exile or removal from society. St. Nicholas teaches that these meditations can be done by all and in every place:

“The general may remain in command, the farmer may till the soil… one need not betake oneself to a remote spot, nor eat unaccustomed food, nor even dress differently... It is possible for one who stays at home and loses none of his possessions to constantly be engaged in the Law of the Spirit [Love]" (Life in Christ, 173-174).

At first glance this might seem a bit simple if not naïve. Go to Liturgy and throughout the week reflect on Christ’s love? St. Nicholas distilling a thousand years of ascetic praxis explained that every action comes from desire and that desire begins with reflection. Christ’s love is reflected on and this turns into desire to be with Christ which leads to actions pleasing to Him. People will act not out of fear of punishment or desire for reward but out of love for Christ.

It is important to remember that these reflections and meditations on Christ throughout the days and weeks can never be independent from the Eucharistic gathering. It is the Ecclesial experience of Christ in the shared meal that is remembered in the midst of the world and daily life and in a very real sense is brought into the world through this remembrance. The Eucharist is never independent of the world because it is carried into the world, relationships, politics, and encounters with culture. In fact St. Nicholas writes that the bread and wine offered in the Liturgy are themselves the fruit of human labor, culture, and are products of daily life.

The Kavasilas option is the “Eucharisteite in all circumstances” of St. Paul’s 1st letter to the Thessalonians (5:18). From this remembering and reflecting, born of these meditations on Christ’s manic love and the experience of the liturgy a eucharisticizing of the world takes place. This is spoken of beautifully by Olivier Clement:

“There is a particular way of washing, a way of dressing, of being nourished—whether through food or beauty—a way of welcoming one’s neighbor that is Eucharistic. It seems to me that there is also a Eucharistic way of fulfilling our dull, tiresome and repetitive daily tasks" (Three Prayers, 29).

What is the Kavasilas Option in the end? It is to be truly human.

“It was for the new man [Christ] that human nature was created at the beginning…Our reason we have received in order that we may know Christ, our desire in order that we might hasten to Him. We have memory in order that we may carry Him in us" (Life in Christ, 190).

The great wonder of Kavasilas’ teaching is that when people live as they were created to live they become, “as a people of gods surrounding God" (Life in Christ, 166). Because Christ:

Gives them birth, growth, and nourishment; he is life and breath. By means of Himself He forms an eye for them and, in addition, gives them light and enables them to see Himself. He is the one who feeds and is Himself the food… Indeed, He is the One who enables us to walk, He Himself is the way, and in addition He is the lodging on the way and its destination… (Life in Christ, 47).

Fr. Micah Hirschy is priest at Holy Trinity Holy Cross Greek Orthodox Cathedral in Birmingham, Alabama.

Public Orthodoxy seeks to promote conversation by providing a forum for diverse perspectives on contemporary issues related to Orthodox Christianity. The positions expressed in this essay are solely the author’s and do not necessarily represent the views of the editors or the Orthodox Christian Studies Center.

Public Orthodoxy | April 27, 2018 at 1:44 pm | Tags: Benedict Option, Fr. Micah Hirshy, Nicholas Kavasilas, Rod Dreher | Categories: Church and Public Life | URL: https://wp.me/p6DEZQ-17I

ORTHODOX PASCHAL CANON

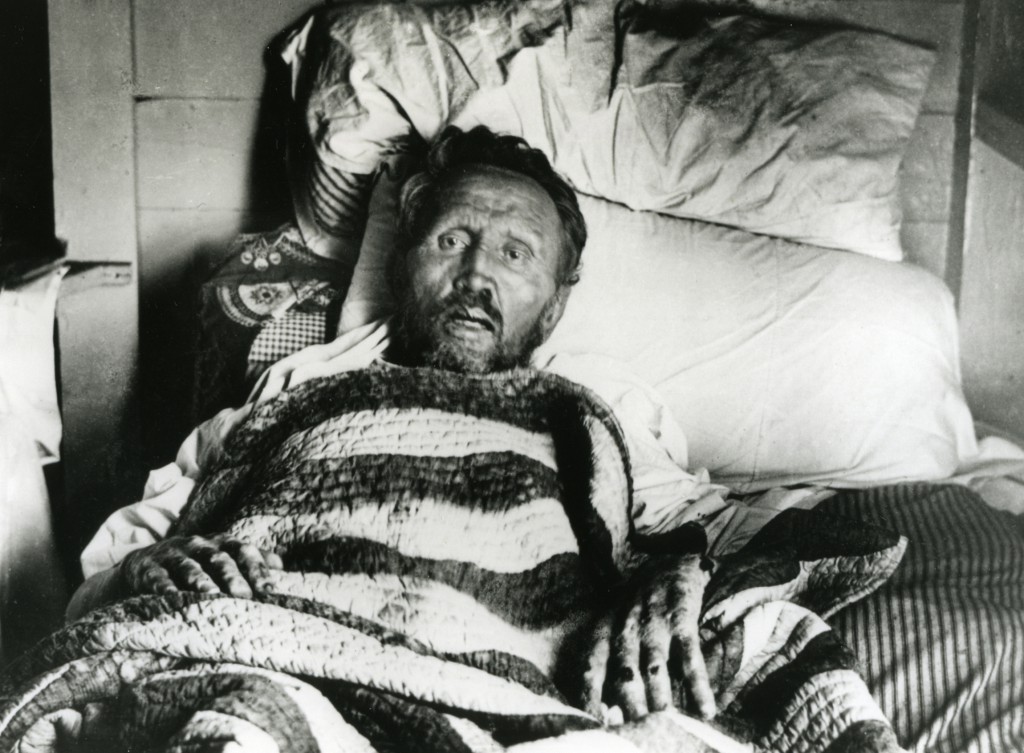

THEY KNEW HIM IN THE BREAKING OF THE BREAD: DOROTHY DAY AND THE EUCHARIST

Jessica Keating

M.Div. Candidate, University of Notre Dame

The liturgy is not merely something one “does” or “performs,” but something one lives and embodies in the concrete circumstances of the world. Pope Benedict XVI, in God Among Us, argues that the reality of the Eucharist makes pressing corporeal demands.

The Lord gives himself to us in bodily form. That is why we must likewise respond to him bodily. That means above all that the Eucharist must reach out beyond the limits of the church itself in the manifold forms of service to men and women and to the world. But it also means that our religion, our prayer, demands bodily expression. Because the Lord, the Risen One, gives us himself in the Body, we have to respond in soul and body. (Benedict XVI)

It is this eucharistic reality which Day strove to embody, convicted of the fact that one cannot go to church, sing with the children, hear the homily of the day, partake of the bread of life, the Word made flesh, hear the Gospel, the Word of God, without allowing what one has received to overflow in loving service for one’s fellows (Day, CW 1949, 5.8). One’s entire corporeal existence is involved in worship and one is likewise obligated, through the grace poured out in Christ’s sacrifice on the cross at Calvary and made real and present in the “Holy Sacrifice of the Mass” through the “unbloodied repetition of the Sacrifice of the Cross” to inhabit the mystery of divine charity which is kenosis (Peter Maurin in Zwick 63; Corbon 241). To say that God’s grace merely invites one to action is limpid, and lacks the bite of the Gospel. Grace demands, shocks, and disorients. Articulating these concrete demands, Day writes:

Every house should have a Christ’s room. The coat which hangs in your closet belongs to the poor. If your brother comes to you hungry and you say, Go be thou filled, what kind of hospitality is that? It is no use turning people away to an agency, to the city or the state or the Catholic Charities. It is you yourself who must perform the works of mercy. … Often you can literally take off a garment if it only be a scarf and warm some shivering brother. But personally, at a personal sacrifice, these were the ways Peter used to insist, to combat the growing tendency on the part of the State to take over. The great danger was the State taking over the job which our Lord Himself gave us to do, “Inasmuch as you did it unto one of the least of these my brethren, you have done it unto me. (Day, CW 1947, 1.3)

God’s grace pressed upon her compelling a personal response, one in which the “mystery of divine love” expressed and actualized in the liturgy became “coextensive” with her life (Corbon 241). This love, which God extends to humanity, permeates “the depths of the heart […with] the power of the crucified and risen Lord,” and is fully realized “when it inspires us to enter into the depths of the world of sin, where love is not yet the conqueror of death” (241).

In The Wellspring of Worship, Jean Corbon remarks,

“The kenosis of love is revealed to us in the Bible as a mystery of poverty…In his person as the Son Jesus reveals to us that God is poor; for Jesus ‘has’ nothing; he receives everything ‘from’ the Father” (241-42). The Eucharist, therefore, quite literally “commits us to the poor” (CCC §1397).

Day, witnessing to this reality, wrote:

The mystery of the poor is this: That they are Jesus, and what you do for them you do for Him. It is the only way we have of knowing and being in our love. The mystery of poverty is that by sharing in it, making ourselves poor in giving to others, we increase our knowledge of and belief in love. (CW, 1956, 2)

She distinguished, however, supernaturally efficacious poverty from “pagan poverty.” The former involves “putting on Christ” while the latter undertaken out of selfishness.

Poverty is no good supernaturally if it is a pagan poverty for the sake of the freedom involved, though that is good, naturally speaking. Poverty is good, because we share the poverty of others, we know them and so love them more. Also, by embracing poverty we can give away to others. If we eat less, others can have more. If we pay less rent, we can pay the rent of a dispossessed family. If we go with old clothes, we can clothe others. We can perform the corporal works of mercy by embracing poverty. If we embrace poverty we put on Christ. If we put off the world, if we put the world out of our hearts, there is room for Christ within. (Day, CW 1944, 1, 2, 7)

Day lived out the mystery of Christ in the poor, practicing the works of mercy. During the 1971 interview on Christopher Closeup, when asked how the soup lines got started, Day matter-of-factly explained:

Our Lord left himself to us as food: bread and wine. The disciples at Emmaus knew him in the breaking of bread and so it’s far easier to see Christ in your brother when you are sitting down and sharing soup with him. You don’t any longer see the destitute, or the drunk, or the disorderly, or the unworthy poor. (Christopher Closeup, 1971)

Furthermore,

“[w]hen you love people, you see all the good in them, all the Christ in them. God sees Christ in His Son, in us and loves us. And so we should see Christ in others, and nothing else, and love them” (Day, Pilgrimage 124).

She considered all her life as a meeting with Christ. “In performing the works of mercy […] she met Christ in human guise. In the Eucharist […] she met Christ disguised in word and human symbol [and] received him sacramentally, and was intimately transformed by him (Merriman 98). Her imagination, so radically reoriented and shaped by the Eucharistic sacrifice, allowed her to see in the daily life of the homeless the laborious and lonely journey to Calvary:

“Here starts their long weary trek to as to Calvary. They meet no Veronica on their way to relieve their tiredness nor is there a Simon of Cyrene to relieve the burden of the cross (Day, Loaves 37).

The liturgical movement, which profoundly affected Day’s understanding of the unity of the life of worship and the life of work, advanced the idea that there was no bifurcation between the activities in which relate Christians to God, sacred actions on the one hand and secular actions on the other (Corbon 204). Unlike the Old Covenant, in which “worship did not contain the saving events within it but simply remembered them [and] its morality aimed at conformity with the events but did not flow from them as from a present source,” the New Covenant celebrated in the liturgy “does not offer us a model that is then to be imitated in the rest of life”; rather the “Christ whom we celebrate is the identical Christ by whom we live” (203-04). There are not two radically heterogeneous realities; rather there is but one reality with two distinctive aspects, in which the mystery of Christ “permeates both celebration and life” (204). The liturgical movement expressed the continuity between moral and cultic life, and Day adopted Fr. Virgil Michel’s attitude that “our responsibility for the poor, believer or not, flows from the fact that we are connected to one another in the mystical Body of Christ and the Eucharist (Day, Pilgrimage 36). In other words, Day believed that one ought to live in conformity to the mystery of Christ’s kenosis and love expressed in the Eucharist.

This is the one whose body we eat and whose blood we drink; the one who, when we commune in the Eucharist takes us out of ourselves and assimilates us into him, so “that we become one with him and, through him, with the fellowship of our brethren” (Benedict XVI 78). Pope Benedict explains that the Eucharist reverses what normally occurs when we take in nourishment. “In the normal process of eating,” he remarks, “the human being is the stronger being. He takes things in, and they are assimilated into him, so that they become part of his own substance. They are transformed within him and go to build up his bodily life” (Benedict XVI). But by taking in the Eucharist, Christ subsumes us into his Body, so that we might not merely imitate, but participate in his poverty, his self-emptying love.

For Day one did not live the liturgy individually in isolation from others. In her autobiography, The Long Loneliness, she recalls:

I had heard many say that they wanted to worship God in their way and did not need a Church in which to praise Him, nor a body of people with whom to associate themselves. But I did not agree to this. My very experience as a radical, my whole make-up, led me to want to associate myself with others, with the masses, in loving and praise God. Without even looking into the claims of the Catholic Church, I was willing to admit that for me she was the one true Church. (139)

Like all human persons, Day had a deep and abiding desire for communion with God, which as the very nature of God reveals, is necessarily relational. Her involvement with the radical movement and the “sense of solidarity” she experience therein enabled Day to “gradually understand the doctrine of the Mystical Body of Christ whereby we are members of one another” (149). Partaking in the liturgy imbued her with the sense of “Eucharistic communion,” which she then extended to the entire human community (Corbon 205). Thus, Day asserts that

“[w]e cannot love God unless we love each other, and to love we must know each other. We know him in the breaking of the bread, and we are not alone anymore” (Day, Long 285).

An Interview with Dorothy Day's Granddaughter

_4.jpg/220px-Benedykt_XVI_(2010-10-17)_4.jpg)