When God became man in Palestine, a new relationship was created between Heaven and earth, Eternity and time: there came into existence the ‘fullness of time’ which culminated in “kairos” of Jesus, the ‘last times’ (eschaton). The “fullness of time” was a direct result of the Incarnation and from Jesus’ true identity as God-man. Just as we identify the persons of the Blessed Trinity only by their relationships with one another, we call God the Father “Father” because of his relationship to the Son, and the Word is “Son” only because of his relationship to the Father, and the Holy Spirit is breathed forth by the Father to become the mutual union of Love between the Father and Son, so the identity of Jesus as a human being can only be thought of correctly in his relationship to his Father in the Holy Spirit, and to the human race in the same Holy Spirit, and especially to the Church. This relationship to the human race is not something that happened after the Incarnation: it is the very meaning of the Incarnation, and a dimension of his identity as the Christ. The title by which Jesus described himself, ‘Son of Man’, implies this corporate personality. Kings in the ancient Middle East were considered the personification of their people: what happened to them was considered to have happened to all their subjects. If they were praised, all felt uplifted; if they were insulted or wounded all screamed for vengeance. What was a pious fiction in the mystique of oriental royalty is literally true of Jesus because of the action of the Holy Spirit from the moment of his conception, uniting him both in the Holy Trinity as Son of God and to the whole human race as Son of Man: this double union constitutes his identity.. Archbishop John Zizioulas writes:

The Holy Spirit does not intervene a posteriori within the framework of Christology, as a help to overcoming the distance between an objectively existing Christ and ourselves; he is the one who gives birth to Christ and to the whole activity of salvation, by anointing him and making him Kristos (Lk 4: 13). If it is truly possible to confess Christ as the truth, this is only because of the Holy Spirit (1 Cor. 12, 3). And as a careful study of 1 Cor. 12 shows, for St Paul, the body of Christ is literally composed of the charismata of the Spirit (charisma = membership of the body). So we can say without risk of an exaggeration that Christ exists only pneumatalogically , whether in his distinct personal particularity or in his capacity as the body of the Church and the recapitulation of all things.

Such is the great mystery of Christology, that the Christ-event is not an event defined in itself – it cannot be defined in itself for a single instant even theoretically - but it is an integral part of the economy of the Holy Trinity. To speak of Christ means speaking at the same time of the Father and the Holy Spirit. For the Incarnation as we have just seen is formed by the work of the Spirit and is nothing else than the expression and realization of the will of the Father.

Hence, everything that Jesus did in life was directly related to his place in the Blessed Trinity and also related to the whole human race of all times and places; and the Holy Spirit is the link at both levels. It can be said that, during his life on earth, Jesus lived about thirty three years of ordinary “horizontal” history and was crucified at the end of it, and that the empty tomb took place three days later around two thousand years ago. However, as God-made-man, there was another “vertical” dimension to his life: he had a relationship with his Father through the Holy Spirit, and it was the Holy Spirit who placed him in contact with all times and, by so doing, made Christ the meaning of all time, making him the universal focal point of all history. For this reason, Christ’s time is called the “fullness of time”.

This “fullness of time” came into existence in the womb of the Blessed Virgin Mary and was completed and reached perfection in Christ’s death which was his doorway into eternity. Thus his life was united to all human lives, and his sufferings were united to all human sufferings, and his fidelity was united to all men in their infidelity and sin. He bore our sufferings and sins, changing suffering into a way to God, seeking and obtaining pardon for all sin, and giving to transient human life a value and a hope it would never have had without him, the capacity to receive eternal life as sons of God, and the means to bring this about. What is impossible for men is possible for God. By means of the Christian Mystery, God was making the impossible possible, “But to all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God, who were born, not of blood or of the will of the flesh or of the will of man, but of God.” (Jn 1, 12).. Because Christ was directly related to all times and places by the activity of the Spirit during his time on earth, God’s revelation in and through Christ in the past became as much God’s revelation to us in the present as it was to his contemporaries. Thus, when the Church sings, “Hodie, Christus natus est”, it is celebrating our contact with the birth of Jesus, which we come to know about through the word of God and celebrate as a true theophany in the liturgy. The activity of the Holy Spirit does not take the event out of the past and put it in the present; he simply bridges the gap between past and present, because the Spirit is outside time and has the same relationship with all times. We are “contemporaries” with Christ’s birth, life, death and resurrection in the Spirit. This fact does not merely justify the “hodie” of the liturgy, it also justifies Catholic devotion to the “Divine Child” or to the “Infant of Prague”, or to the Passion of Christ in its historical details, as the Franciscans and Passionists have favoured. Thus, although the death of Christ is an historical event, the memory of which has been passed down from one generation to the next, it is also a reflection of the presence in each generation of the Holy Spirit who makes the event the supreme revelation of God to us in the present, in spite of being an event in the past.

Nevertheless, his death is not only the climax of the ‘fullness of time’, it is also Christ’s kairos, the time that will truly last for ever, the time that is actually present in the liturgy. To discover this we must look at his death from a completely different angle, as the radical self-giving in love by Jesus himself, an offering for all eternity because it is without limits, a total submission to the will of the Father without reserve or limitation. This self-offering was Christ’s act of voluntarily dying in loving obedience to the Father; and it became a permanent dimension of the risen Christ, an essential characteristic of the eternal relationship of his glorified humanity to the Father, without losing contact with its historical context, because there is no time in heaven. Thus he is depicted in the Book of Revelation as the Lamb “slain but standing” (). Fr Jean Corbon writes of Christ’s death:

Above and beyond its historical circumstances, which are indeed of the past, the death of Jesus was by its nature the death of death. But the event wherein death was put to death cannot belong to the past, for then death would not have been conquered. To the extent that it passes, time is the prisoner of death; once time is delivered from death, it no longer passes. The hour on which the desire of Jesus was focused “has come, and we are in it” forever; the event that is the Cross and Resurrection does not pass away. (The Wellspring of Worship by Jean Corbon, Ignatius Press, pg 56)

Thus, by means of his ascension into the presence of his Father, this passage of Jesus through death and resurrection has become the permanent means for human beings and even for the whole universe to be transformed into sharers of the divine life. Hence, we who live in time are destined to ascend, through his death and resurrection, into the presence of the Father. By dying on the cross and entering heaven by resurrection-ascension, Christ has brought about a new way of being human. By passing through his death to share in his resurrected life, the whole creation is destined to be transformed into “the new heaven and new earth” spoken about in the Apocalypse; and this is already a living reality in Christ in heaven. It is into this reality that the Church passes every time it celebrates Mass. His pasch has become our pasch, his mystery our mystery. We are baptised into his death and resurrection and celebrate the same mystery of our participation in this process at every Mass. Once in his presence, we receive eternal life from the Father, a life that belongs by right to the human nature of the risen and ascended Christ, but which he shares with us through the Spirit who makes us one body with him. Sharing in his human nature that has been transformed by resurrection, we share in his divine life and also share in his joy

When we ‘ascend’ in the Mass to the heavenly sanctuary into the presence of the Father through the veil that is Christ’s flesh, our baptism and confirmation are renewed. In the words of St Ambrose, “By his Ascension, Christ passed into his mysteries.” Corbon, “The Wellspring of Worship, pg 98). In our communion with the risen Christ in heaven, all our sacraments, our baptism and confirmation, our ordination or marriage, are rejuvenated and become again and again, active means of grace, because we have been united by the Spirit to their Source who is Christ. The death of Christ is like a black hole through which the whole human race, and indeed, the whole of creation have to pass in order to bring into existence a ‘new heaven and a new earth’.

The Gospel of St Mark is said to be simply an account of the Passion of Christ, with a long prologue which tells of his public ministry, and an epilogue which tells of his Resurrection. It is clear that, for St Mark, his Passion is the most important revelation of all. St Matthew’s account links the death of Christ in apocalyptic fashion with the emptying of the tombs and the resurrection of the dead (Mt 27, vv 51 – 54). St John’s Gospel also attaches to Christ’s death on the cross many of the ideas that belong to the Last Day in other gospels. For instance, when Jesus is lifted up (crucified) he will draw all men to himself (); in the cross, Jesus and his Father are glorified (); and the crucifixion is the Judgement of the world ( ). Moreover, the coming of the Holy Spirit into the world is linked with Christ’s death on the cross( ).. He tells Simon Peter before the crucifixion that he is going on a journey and that Si Peter cannot go with him now, but that one day he will be able to go (Jn 13 ) It implies that accompanying Jesus through death to resurrection is a future option for Simon Peter, and for us. It is not only a historical memory, however direct may be our contact with this event through the memory of the Church: through it Christ in the ‘fullness of time’ and we in our own time pass into the ‘eschaton’. .

In his “presentation” of Liturgia y Oracion by Fr Jean Corbon, Prof. Felix Maria Arocena of the University of Navarre in Spain tells us that there is an altar in the church of the Convento de San Bernadino de Siena in Bergamo which illustrates the confluence of our historic memory of the Passion with our participation in Christ’s sacrifice of the Mass. Caravaggio so painted his picture of the Passion that, every time the priest elevates the host at Mass, we become aware of the two ways in which we are brought into contact with the cross, with the historical event through the memory of the Church as depicted in the painting, and with the same event as our door into eternity, our way to God through the Eucharist. On Good Friday and Holy Saturday, the Church takes its normal emphasis away from the Eucharist in which the death and resurrection of Christ are united together as one single mystery, and concentrates on the historical event where the resurrection was in the future, and Jesus cried out, “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me!”. We do this because, through the action of the Holy Spirit, the crucifixion of Jesus is the clearest and most intimate theophany (manifestation of God) in human history, not only for Our Lady and St John on the day, but for us and for all believers until the end of time.

This passage of Jesus through death to resurrection and ascension into the presence of the Father is celebrated for all eternity by the angels and saints in heaven, as they share the joy of the Father at the arrival in heaven of his only begotten Son, and they share in the joy of Jesus as he is accompanied by those whom he has saved – “A great multitude that no one could count, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and languages” from all times and places – streaming into the heavenly Jerusalem with him. This is the heavenly liturgy.

One direct result of the ascension was the pouring out of the Holy Spirit on the Church at Pentecost. In this reason we can say that the ascension of Christ is the epiclesis which is the cause of every other epiclesis in Catholic liturgy. Indeed, Pentecost is the origin of the Liturgy of the Church. According to P. Jean Corbon OP, (The Wellspring of Liturgy), the Liturgy is brought about by the synergy (harmony or synchronization between two “energies” or activities) between the activity of the Holy Spirit and that of the Church which brings about the Church’s liturgy. In this relationship, the Church is pure need, but the Holy Spirit enables it to do what would be impossible without the Spirit.

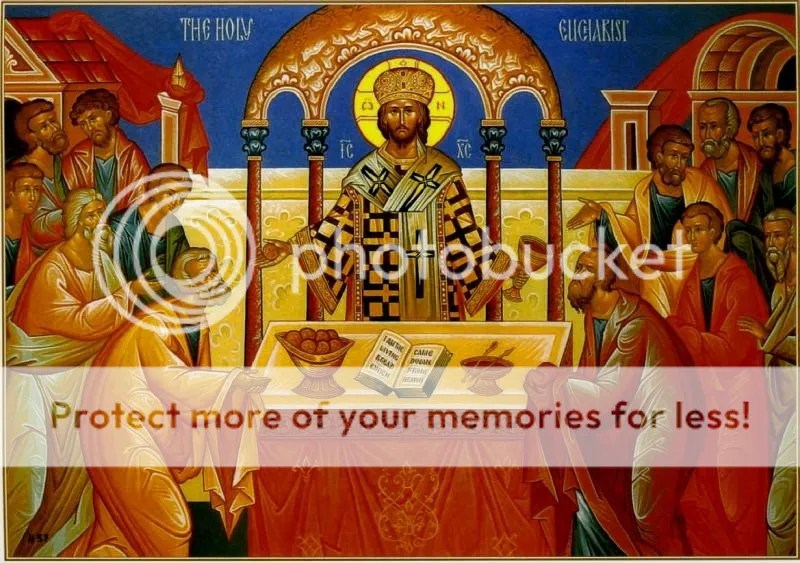

"Do this in memory of me" (Luke 22,19; 1 Cor. 11,24.25). It is following this command of the Lord that the Church has always understood, from its very beginning, the great mystery it was to guard and that the Church was called upon to transmit faithfully over the centuries until the glorious return of Christ. Even when the first Christians continued to go and pray in the temple (see At 2,42; 5,12; 3,1), the first act that allowed them to identify themselves as a new community, was the celebration of the "new Easter". Using a surprising denomination, they indicated in the "breaking of the bread" the novelty of their prayers. This consisted in listening to the Word, in remembering the death and resurrection of the Lord and joyfully awaiting the day of His return; the prayers for giving thanks, the Eucharistic prayer, was established from the very beginning as the recollection of the Lord’s supper which took place before his death on the Cross (see 1 Cor 11,26).

The Eucharist therefore is understood as an act created by Jesus himself, placed within the history of Salvation, in the period of time that elapsed between his death and his return in the parousia. The eschatological conscience that accompanied this prayer, therefore constitutes one of the peculiarities that characterize its meaning and allows its integral preservation until the Lord Jesus shall accomplish the "restoration of all things" (At 3,20). The cry of Marana-tha ("Come, Our Lord!"), pronounced during the Lord’s supper, strongly attests to what extent the first community felt the Lord’s presence close to them and to what extent they rejoiced in thanking Him (ευχαριστουντες Eph 5,20), without however forgetting that the fullness of communion had not yet been fully been donated and for this reason they invoked His return. It was this Eucharistic awareness that allowed the first community to experiment in a totally particular manner the closeness, the presence and the communion with the Lord Jesus and it was this that allowed it to confront in a heterogeneous manner the Judaic cult and any other pagan sacrificial action (see 1 Cor 10,16-22). The participation in the body and the blood of Christ went well beyond any analogy, because it involved the real presence of the Lord and real communion with Him. This dimension, which already exists in the signs and the words reveals the sacrificial sense of the Eucharistic banquet, has always allowed believers to build and to strengthen the bonds with their brothers (the "saints" of At 9,13) to the pointing of calling themselves for this reason "God’s community", "the holy assembly" and "the Lord’s people". Finally, it is from Eucharistic life that this community received the strength to lead a moral life that was coherent and a source of testimony. Paul’s invitation to "examine oneself" so as to be worthy of sitting at the Eucharistic banquet is an indication of a conscience capable of perceiving the rules of its own existence in conformity with the mystery it celebrates. These elements allowed them to become aware that it was in the Eucharist that the believing community always found the origin of its being "only one body", "the body of Christ and members of member" (1 Cor 12,27).

This brief introduction, that creates the essential scenario for theologically approaching the subject of the Eucharist, allows us to verify the fundamental and constituent points of this mystery. First of all, there is no rift between Jesus’ established act during the last supper, "the eve of his passion" or "the night on which he was betrayed" and the believing community’s successive customs. This custom has simply repeated and celebrated only what Jesus himself had indicated and commanded to be repeated after his death. Any historical-critical analysis that might attempt to separate these two moments, insinuating that the "Lord’s Supper" is a composition of the community, is destined to disintegrate when confronting the historical evidence which has no analogies with other cultural celebrations and the very self-awareness of the primitive community. The conformity with the entire message announced by the Lord and the events of His death and Resurrection discovers its most coherent and original synthesis in this command to pass down the actions of the Last Supper. With this command for the anamnesis, He impresses the seal of His real presence among His faithful and His Disciples beyond His death. A single act that is not characterized by a tired repetition or representation, but that on the contrary, presents itself as the apax efapax in its unrepeatability. The very words zikkārōn, anamnesis, memory simply interpret the uniqueness of the act in its ever-lasting historical presentation.

The historical and theological development that took place during the first centuries, and of which the Fathers have left us a precious testimony, becomes real in the various passages that progressively lead to the verification of the public characteristics of the liturgical action. The building of the first basilicas with their circular shape, the centrality of the altar added to the solemnity of the celebration are the testimony of the progress that occurred starting with the foundations of Eucharistic life within the Church. Thomas, with the Scholastic will lead to a meditation of the sacramental characteristics of the Eucharist. It is sufficient to read once again some of the questiones (73-79) in the III Pars of the Summa Theologiae so as to verify the deep theological unity that is achieved in the analysis of the signum et res and of the sacrificium laudis et crucis. Regarding the meaning of the Eucharist Thomas wrote: "This sacrament has three meanings. The first concerns the past, because it commemorates the Lord’s passion which was a real sacrifice… The second concerns the effect of the present representing the unity of the Church in which mankind is united through this sacrament. For this reason it is called communion or synaxis… The third concerns the future: because this sacrament is prefigurative of the divine beatitude which will occur in the homeland. In this sense it is called viaticum, because it shows us the path for achieving it and for the same reason it is also described as the Eucharist, the good grace". As one can see, the triple distinction of the sacrament as signum rememorativum (because it proves the uniqueness of the redeeming act), demonstrativum (in the sense that it accomplishes the announced redemption) and prognosticum (because it is the anticipation of the Eschatological banquet), find in these words their theological importance. The antiphon to the Magnificat in the Corpus Domini feast simply evokes liturgically in a poetic synthesis the theological intuition: "Recolitur memoria passionis eius, mens impletur gratiae et futurae gloriae nobis pignus datur".

The Tridentine was to mark a fundamental moment in the history of the dogma. Contrary to the Protestant interpretation according to which Christ’s presence is produced by faith, the Councilior Fathers affirmed that Christ is not present in the Eucharist simply because we believe He is, but that we believe because He is already present and that He is not absent because we do not believe, but He remains with us so that we may live in communion with Him (see DS 1654). In the history of the development of this dogma, the Tridentine stage clearly underlines the deep emphasis concerning the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. The expiratory finality and the sacrificial character of the Eucharist mark in a decisive manner the theology of this sacrament and the terminology achieves its irreversible dogmatic depth. The Tridentine affirmations lead, as is well known, to the successive controversy that essentially concerned the sacrificial nature. A debate and a theological meditation that reached our times in a interpretative "muddle".

The Second Vatican Council certainly marks a fundamental stage in liturgical, theological and pastoral reform of the sacrament. Although it does not include as specific document concerning the sacrament, the second chapter of the Sacrosanctum concilium can be considered a decisive point on this subject. Because the Council keeps its eyes firmly fixed on the Church, the Eucharist is understood in a binding relationship with the life of the Christian community for which it is the "summit and the source" (LG 11). The terminological variety with which the sacrament is described in the more or less 100 passages of the different documents of the Council, shows on one hand a dogmatic richness and on the other the difficulty in synthesizing the teachings it contains. At least two fundamental issues certainly flow into the teachings of the Council that had determined previous theological reflections.

The first, essentially is referred to Odo Casel’s studies (+1948) with his theory of "renewed-presentation". He claims that in the Eucharist the mystery re-presents itself, meaning a renewed-enacting in favor of the community that celebrates it. The Holy Mass, therefore confers a presence of a trans-temporal and trans-locational nature to the mystery of the Cross. Having removed the reference to a dependence for mystery cults, Casel’s theory had various supporters who continued to favor his interpretations relying in particular on the dimension of the characteristics of the new and definite alliance of the Eucharist. The second, refers to studies by M.Thurian and Louis Bouyer that instead reproposes the notion of a memorial as the sacred pledge that God offered to His people so that they would uninterruptedly represent this to Him. In this manner, they attempt to meditate even more on the essential connection that there is between the memorial, the sacrifice and the banquet.

These brief concise outlines only intend to reproposes the plurality of the interpretations that concern this sacrament. The theological accentuations that we find concern in turn a number of particular subjects that can be synthesized as follows:

1. The concept of memoria (anamnesi), where the institution’s central and founding event finds its basis and its original unity in Jesus’ act at the Last Supper.

2. The concept of giving thanks (beraka), in which the gratefulness of the faithful for the supreme gift they have received becomes clear. Hence the sense of the divine cult, of the glorification, praise and adoration that the community addresses to the Father for the wonders He as accomplished and of which they His people are the witness.

3. The concept of sacrifice (thysia), in which the renewed-presentation of Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross is underlined as an act of redemption involving both His body and the Church.

4. The concept of epiclesi with which the interior action of the invocation of the Spirit, who works and accomplishes the Eucharistic act, is stressed. This presence and work of the Holy Spirit in the Eucharist is synthesized in Ippolito the Roman’s anaphora, were one prays to God the Father saying: "Allow your Holy Spirit to descend upon the offering of your Holy Church, and after reuniting them, concede to all the Saints who receive it to be filled by the Holy Spirit so as to fortify them in the faith and in the truth, that we may praise you and glorify you through your Son Jesus Christ, through whom you receive the glory and the honor, Father and Son with the Holy Spirit within the holy Church now and for ever and ever" (Apostolic Tradition, 4). It is the prayer that requests the benediction of the Lord and that is celebrated by the Church as blessing the Lord Himself, according to Paul’s expression: "the chalice of benediction which we bless" (1 Cor 10,16).

5. Il concept of communion, with which one intend to infer the aim of the Eucharist and its accomplishment. The new alliance that Christ enacts with His blood creates the life of the Church and for the church stating the premise of redemption. None as well as Saint Augustine have been capable of understanding the connection in this relationship: "If you are to understand the body of Christ, listen to the Apostles who tell the faithful: Now you are the body of Christ, and members of member (1 Cor 12,27). If therefore you are the body of Christ and his limbs, your holy mystery is placed on the table of the Lord: you shall receive your holy mystery. To what you are you answer Amen and by answering you undersign it. In fact you hear: "the body of Christ" and you answer: "Amen". Really become the Body of Christ, so that the Amen (that you pronounce) shall be true!" (Sermon 272).

6. The eschatological concept, with which one insists on the final and preparatory characteristics of the Eucharist. "While awaiting His coming" repeated after the consecration clearly certifies the Eschatological intent that the Eucharistic supper contains as the affirmation and the anticipation of new heavens and earth in the Kingdom of God.

A text written by the great Catholic theologian M. J. Scheeben, allows us to synthesize the various elements we have tried to examine: "The Eucharist –he writes in The mysteries of Christianity- is the real and universal continuation and amplification of the mystery of the Incarnation. Christ’s Eucharistic presence is in itself a refection of a amplification of His Incarnation... The transformation of the bread into the Body of Christ thanks to the Holy Spirit is a renewal of the wonderful act with which He originally formed his Body from the breast of the Virgin by virtue of the Holy Spirit Himself and took this body onto His person: and of how, thanks to this act, he entered the world for the first time, hence in this transformation He multiplies His essential presence through space and time". The Eucharist, finally, remains the rule for correct theological thought; we are reminded of this by Saint Ireneus who wrote: "Our doctrine is in agreement with the Eucharist and the Eucharist confirms it" (Against Heresy IV, 18, 5).

+ Rino Fisichella

The Eucharist memory of the Paschal Mystery

"Do this in memory of me" (Luke 22,19; 1 Cor. 11,24.25). It is following this command of the Lord that the Church has always understood, from its very beginning, the great mystery it was to guard and that the Church was called upon to transmit faithfully over the centuries until the glorious return of Christ. Even when the first Christians continued to go and pray in the temple (see At 2,42; 5,12; 3,1), the first act that allowed them to identify themselves as a new community, was the celebration of the "new Easter". Using a surprising denomination, they indicated in the "breaking of the bread" the novelty of their prayers. This consisted in listening to the Word, in remembering the death and resurrection of the Lord and joyfully awaiting the day of His return; the prayers for giving thanks, the Eucharistic prayer, was established from the very beginning as the recollection of the Lord’s supper which took place before his death on the Cross (see 1 Cor 11,26).

The Eucharist therefore is understood as an act created by Jesus himself, placed within the history of Salvation, in the period of time that elapsed between his death and his return in the parousia. The eschatological conscience that accompanied this prayer, therefore constitutes one of the peculiarities that characterize its meaning and allows its integral preservation until the Lord Jesus shall accomplish the "restoration of all things" (At 3,20). The cry of Marana-tha ("Come, Our Lord!"), pronounced during the Lord’s supper, strongly attests to what extent the first community felt the Lord’s presence close to them and to what extent they rejoiced in thanking Him (ευχαριστουντες Eph 5,20), without however forgetting that the fullness of communion had not yet been fully been donated and for this reason they invoked His return. It was this Eucharistic awareness that allowed the first community to experiment in a totally particular manner the closeness, the presence and the communion with the Lord Jesus and it was this that allowed it to confront in a heterogeneous manner the Judaic cult and any other pagan sacrificial action (see 1 Cor 10,16-22). The participation in the body and the blood of Christ went well beyond any analogy, because it involved the real presence of the Lord and real communion with Him. This dimension, which already exists in the signs and the words reveals the sacrificial sense of the Eucharistic banquet, has always allowed believers to build and to strengthen the bonds with their brothers (the "saints" of At 9,13) to the pointing of calling themselves for this reason "God’s community", "the holy assembly" and "the Lord’s people". Finally, it is from Eucharistic life that this community received the strength to lead a moral life that was coherent and a source of testimony. Paul’s invitation to "examine oneself" so as to be worthy of sitting at the Eucharistic banquet is an indication of a conscience capable of perceiving the rules of its own existence in conformity with the mystery it celebrates. These elements allowed them to become aware that it was in the Eucharist that the believing community always found the origin of its being "only one body", "the body of Christ and members of member" (1 Cor 12,27).

This brief introduction, that creates the essential scenario for theologically approaching the subject of the Eucharist, allows us to verify the fundamental and constituent points of this mystery. First of all, there is no rift between Jesus’ established act during the last supper, "the eve of his passion" or "the night on which he was betrayed" and the believing community’s successive customs. This custom has simply repeated and celebrated only what Jesus himself had indicated and commanded to be repeated after his death. Any historical-critical analysis that might attempt to separate these two moments, insinuating that the "Lord’s Supper" is a composition of the community, is destined to disintegrate when confronting the historical evidence which has no analogies with other cultural celebrations and the very self-awareness of the primitive community. The conformity with the entire message announced by the Lord and the events of His death and Resurrection discovers its most coherent and original synthesis in this command to pass down the actions of the Last Supper. With this command for the anamnesis, He impresses the seal of His real presence among His faithful and His Disciples beyond His death. A single act that is not characterized by a tired repetition or representation, but that on the contrary, presents itself as the apax efapax in its unrepeatability. The very words zikkārōn, anamnesis, memory simply interpret the uniqueness of the act in its ever-lasting historical presentation.

The historical and theological development that took place during the first centuries, and of which the Fathers have left us a precious testimony, becomes real in the various passages that progressively lead to the verification of the public characteristics of the liturgical action. The building of the first basilicas with their circular shape, the centrality of the altar added to the solemnity of the celebration are the testimony of the progress that occurred starting with the foundations of Eucharistic life within the Church. Thomas, with the Scholastic will lead to a meditation of the sacramental characteristics of the Eucharist. It is sufficient to read once again some of the questiones (73-79) in the III Pars of the Summa Theologiae so as to verify the deep theological unity that is achieved in the analysis of the signum et res and of the sacrificium laudis et crucis. Regarding the meaning of the Eucharist Thomas wrote: "This sacrament has three meanings. The first concerns the past, because it commemorates the Lord’s passion which was a real sacrifice… The second concerns the effect of the present representing the unity of the Church in which mankind is united through this sacrament. For this reason it is called communion or synaxis… The third concerns the future: because this sacrament is prefigurative of the divine beatitude which will occur in the homeland. In this sense it is called viaticum, because it shows us the path for achieving it and for the same reason it is also described as the Eucharist, the good grace". As one can see, the triple distinction of the sacrament as signum rememorativum (because it proves the uniqueness of the redeeming act), demonstrativum (in the sense that it accomplishes the announced redemption) and prognosticum (because it is the anticipation of the Eschatological banquet), find in these words their theological importance. The antiphon to the Magnificat in the Corpus Domini feast simply evokes liturgically in a poetic synthesis the theological intuition: "Recolitur memoria passionis eius, mens impletur gratiae et futurae gloriae nobis pignus datur".

The Tridentine was to mark a fundamental moment in the history of the dogma. Contrary to the Protestant interpretation according to which Christ’s presence is produced by faith, the Councilior Fathers affirmed that Christ is not present in the Eucharist simply because we believe He is, but that we believe because He is already present and that He is not absent because we do not believe, but He remains with us so that we may live in communion with Him (see DS 1654). In the history of the development of this dogma, the Tridentine stage clearly underlines the deep emphasis concerning the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. The expiratory finality and the sacrificial character of the Eucharist mark in a decisive manner the theology of this sacrament and the terminology achieves its irreversible dogmatic depth. The Tridentine affirmations lead, as is well known, to the successive controversy that essentially concerned the sacrificial nature. A debate and a theological meditation that reached our times in a interpretative "muddle".

The Second Vatican Council certainly marks a fundamental stage in liturgical, theological and pastoral reform of the sacrament. Although it does not include as specific document concerning the sacrament, the second chapter of the Sacrosanctum concilium can be considered a decisive point on this subject. Because the Council keeps its eyes firmly fixed on the Church, the Eucharist is understood in a binding relationship with the life of the Christian community for which it is the "summit and the source" (LG 11). The terminological variety with which the sacrament is described in the more or less 100 passages of the different documents of the Council, shows on one hand a dogmatic richness and on the other the difficulty in synthesizing the teachings it contains. At least two fundamental issues certainly flow into the teachings of the Council that had determined previous theological reflections.

The first, essentially is referred to Odo Casel’s studies (+1948) with his theory of "renewed-presentation". He claims that in the Eucharist the mystery re-presents itself, meaning a renewed-enacting in favor of the community that celebrates it. The Holy Mass, therefore confers a presence of a trans-temporal and trans-locational nature to the mystery of the Cross. Having removed the reference to a dependence for mystery cults, Casel’s theory had various supporters who continued to favor his interpretations relying in particular on the dimension of the characteristics of the new and definite alliance of the Eucharist. The second, refers to studies by M.Thurian and Louis Bouyer that instead reproposes the notion of a memorial as the sacred pledge that God offered to His people so that they would uninterruptedly represent this to Him. In this manner, they attempt to meditate even more on the essential connection that there is between the memorial, the sacrifice and the banquet.

These brief concise outlines only intend to reproposes the plurality of the interpretations that concern this sacrament. The theological accentuations that we find concern in turn a number of particular subjects that can be synthesized as follows:

1. The concept of memoria (anamnesi), where the institution’s central and founding event finds its basis and its original unity in Jesus’ act at the Last Supper.

2. The concept of giving thanks (beraka), in which the gratefulness of the faithful for the supreme gift they have received becomes clear. Hence the sense of the divine cult, of the glorification, praise and adoration that the community addresses to the Father for the wonders He as accomplished and of which they His people are the witness.

3. The concept of sacrifice (thysia), in which the renewed-presentation of Christ’s sacrifice on the Cross is underlined as an act of redemption involving both His body and the Church.

4. The concept of epiclesi with which the interior action of the invocation of the Spirit, who works and accomplishes the Eucharistic act, is stressed. This presence and work of the Holy Spirit in the Eucharist is synthesized in Ippolito the Roman’s anaphora, were one prays to God the Father saying: "Allow your Holy Spirit to descend upon the offering of your Holy Church, and after reuniting them, concede to all the Saints who receive it to be filled by the Holy Spirit so as to fortify them in the faith and in the truth, that we may praise you and glorify you through your Son Jesus Christ, through whom you receive the glory and the honor, Father and Son with the Holy Spirit within the holy Church now and for ever and ever" (Apostolic Tradition, 4). It is the prayer that requests the benediction of the Lord and that is celebrated by the Church as blessing the Lord Himself, according to Paul’s expression: "the chalice of benediction which we bless" (1 Cor 10,16).

5. Il concept of communion, with which one intend to infer the aim of the Eucharist and its accomplishment. The new alliance that Christ enacts with His blood creates the life of the Church and for the church stating the premise of redemption. None as well as Saint Augustine have been capable of understanding the connection in this relationship: "If you are to understand the body of Christ, listen to the Apostles who tell the faithful: Now you are the body of Christ, and members of member (1 Cor 12,27). If therefore you are the body of Christ and his limbs, your holy mystery is placed on the table of the Lord: you shall receive your holy mystery. To what you are you answer Amen and by answering you undersign it. In fact you hear: "the body of Christ" and you answer: "Amen". Really become the Body of Christ, so that the Amen (that you pronounce) shall be true!" (Sermon 272).

6. The eschatological concept, with which one insists on the final and preparatory characteristics of the Eucharist. "While awaiting His coming" repeated after the consecration clearly certifies the Eschatological intent that the Eucharistic supper contains as the affirmation and the anticipation of new heavens and earth in the Kingdom of God.

A text written by the great Catholic theologian M. J. Scheeben, allows us to synthesize the various elements we have tried to examine: "The Eucharist –he writes in The mysteries of Christianity- is the real and universal continuation and amplification of the mystery of the Incarnation. Christ’s Eucharistic presence is in itself a refection of a amplification of His Incarnation... The transformation of the bread into the Body of Christ thanks to the Holy Spirit is a renewal of the wonderful act with which He originally formed his Body from the breast of the Virgin by virtue of the Holy Spirit Himself and took this body onto His person: and of how, thanks to this act, he entered the world for the first time, hence in this transformation He multiplies His essential presence through space and time". The Eucharist, finally, remains the rule for correct theological thought; we are reminded of this by Saint Ireneus who wrote: "Our doctrine is in agreement with the Eucharist and the Eucharist confirms it" (Against Heresy IV, 18, 5).

+ Rino Fisichella