We are continuing to find articles on Pentecost long after Pentecost is over, which makes me wish that we still had "time after Pentecost". I know that Pentecost is the feast that completes the Paschal Mystery which leads up to it. Nevertheless, the time of the Church is not so much the "time after Pentecost" as the "time IN Pentecost", because the Holy Spirit is still coming down. We live in the situation, in the context of Pentecost. In fact, the Church is no less in Pentecost as were the Apostles; and our understanding of Christ's revelation, whether we belong to East or West, reflects this. After all, we are integral parts of the same Eucharist.

It follows that we must take seriously not only all we have in common - I have never read anything of Metropolitan Anthony which has not illumined my path as a Catholic - but we must take seriously our objections against each other. They are not like the objections of the Protestant Reformation, even though these Protestant objections have sometimes been adopted by Orthodox in their verbal conflicts with Catholics. Authentic Orthodox objections arise, not from a rejection of Tradition, but from fidelity to their own Tradition which, for a thousand years at least, was identical to our own. Once both sides accept that the two versions of Tradition, separated from each other by the schism, are rooted in a more fundamental unity brought about by the Holy Spirit in the celebration of the same Eucharist, then they might be able to accept the need to understand each other, as is being done in the Orthodox - Catholic dialogue. However, I accept the Russian Orthodox claim that this will not happen until we discover the need for each other in our ordinary, day-to-day ecclesial lives. Meanwhile, let us both concentrate on the re-conversion of Europe, discover our true identity in the other.

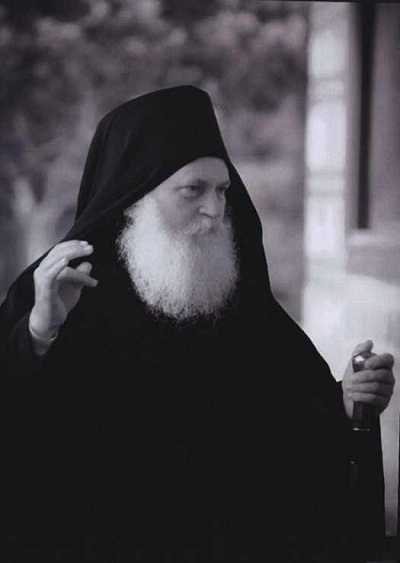

The colour of Pentecost in the East is green, the colour of life; and churches are decorated with branches, as in the photo above.

In the name of the Father, the Son and the Holy Ghost.

The Church of God is not an institution, it is a miracle and it is a mystery. It is a miracle because who and how could we expect that closeness of God which is revealed to us in the Church. And it is also a mystery in the original sense of the world, something which cannot be either explained or conveyed in words, something that can be known only through a spellbound communion with God. The English word “God” comes from a Germanic root that means “him, before whom one prostrates in adoration”. This is where our knowledge of God begins – the sense of the divine presence that forces us down to our knees, spellbound, silent, not with an empty silence that is ours at times but with a silence which is nothing but intent worshipful listening, listening to the presence, listening to that presence which is at the core of the silence. And he who speak to us within this silence is the Holy Spirit, who unveils before our minds and hearts what the words spoken by God, revealed to us in the Gospel truly convey. It is only under the guidance of the Holy Spirit that we can both believe and understand what Christ spoke because words in themselves are always equivocal, they may be clear or obscure, they may be made to mean what they never meant. And this is the role of the Holy Spirit — to make us understand God’s word as it was born in the divine silence and unfolded before us in words which we could understand. But these words are not a prison, they are an open door as Christ is the door leading to the Father and leading to eternal life. It is the Holy Spirit who according to the promise of our Lord unveils for us the meaning of the Scriptures, it is not scholarship, it is worship and a worship that allows us to commune with the mind of God and the heart of God. The Spirit of truth, but also Him whom the Scripture calls the Paraclete, a complex word as so many of the words of ancient languages. It means “the Comforter”, Him who gives consolation. It means ‘Comforter’ in the sense that He gives us strength, it means also “Him, who brings joy”. And these three meanings are important but He can be to us the Comforter in these various ways only if we are in need of His comfort.

What kind of consolation do we need? Most of us feel perfectly comfortable in our lives and indeed in our worship and our spiritual lifem and who of us is in a position to say with all the intensity and depth with which St. Paul spoke these words, “For me life is Christ, death would be a gain because as long as I live in the body, I am separated from Christ.” Can we honestly say that for us life is Christ, that all that He stands for is life-giving, all that is contrary to Him, to us is death? Can we say that we have died with Christ to everything which is alien to God? Can we say that we are alive only when the things of God come our way — prayer, deep meditation, the kind of understanding which the Spirit of God reveals to us? And so we must ask ourselves very sternly a first question: is Christ my life or not? Would it be enough for me to feel that life is fulfilled, complete to be at one with Christ in all things or do I feel that there are so many things which I love and which I am not prepared to let go off even to be with Christ?

And again, Christ is in the midst of us invisibly, mysteriously. Yes, but He is not with us in the way in which He was with the Apostles. We cannot say with St. John that we speak of what we have seen, what we have heard, what our hands have touched. We know Christ in the spirit, no longer in the flesh, and yet Christ rose in the flesh, Christ ascended and is seated at the right hand of the Father in His body glorified. Paul longed to be with Him in this companionship full of veneration, of reverence, of love. He wanted to be at one with Him without anything separating from Him. Who shall make me free of this body of corruption, of this body against which my thoughts and my prayers and my best inclinations, and my most passionate impulses for good break down? Can we say that? Is death what we expect longingly because it will unite us to Christ? Or are we still pagan at heart and do we wish to flee from death? And instead of saying, “Lord, Jesus, come and come soon,” aren’t we prepared to say, “Tarry, o Lord, tarry, give me time,” in the way in which Augustine prayed to the Lord after his conversion, “Lord, give me chastity but not just now.” Isn’t it that our condition — not concerning chastity alone but everything in life: not just now, o Lord, the time will come when all my energies will be spent, when age will have come and made life much less attractive or unpalatable — then take me. No, this is not it. And so when we think of the Holy Spirit as our Comforter, as one who consoles us from the absence of Christ by making us to commune with the essence of things, where do we stand? Is He our Comforter while we need no comfort?

And again, in our ministry how often do we feel that we are totally, ultimately helpless, that what we are called to do is simply beyond human possibilities? In the beginning of the Eucharistic celebration in the Orthodox Church, when the priest is vested, when he has prepared the Holy Gifts, when he is about to give the first liturgical exclamation, when in his naivety he may think, “Now I will perform miracles on earth,” the deacon turns to him and says, “And now, father, it is for God to act.” All you could do, you have done, you have prayed and prepared yourself, made yourself open to God, you have vested yourself and become an image – but only an image not the thing. You have prepared the bread and the wine and now what is expected of you is something which you cannot do, you cannot by any power including apostolic succession make this bread into the Body of Christ, this wine into the Blood of Christ, you have no power over God and you have no power over the created world. It is only Christ who is the only celebrant because He is the High Priest of all creation who sending the Holy Spirit can break through into time, open it up so that eternity can flow, indeed, make eruption into it and within this eschatological situation in which eternity fills time make possible the impossible, make bread into the Body of Christ crucified and risen, the wine into the Blood of Christ crucified and risen.

And all our function depends only on the Holy Spirit. Strength? St. Paul hoped for strength, he prayed for it and the Lord answered him, “My grace suffices unto thee, My strength is made manifest in weakness.” And Paul rejoices in his weakness, so, he says, that all should be the power of God. Not the weakness of our slackness, of our laziness, of our timidity, of our cowardice, of our forgetfulness, no, not that weakness but the frailty recognised, which is given to God, the surrender of ourselves.

If I may use an image, it is that of the sail of a sailing ship. Of all the parts of the ship the sail is the frailest, the weakest and yet filled with the wind, and the word “wind” in ancient languages is the same as “spirit” “ruah”, “πνευμα” it can carry the heavy structure of the ship to its haven. This is the kind of weakness, of frailty which we have got to offer to God, such frailty that He can use it freely, without resistance, and then our strength will be stronger than anything which the created world can possess. The martyrs were frail, as frail as we were, but they abandoned themselves to God and they lived and died in the power of the Spirit. We need that strength.

And then the Paraclete is the one that gives joy, the joy of entering already now into eternity, the joy of being joined to Christ in the communion of the one body, the joy of giving our lives for Him and if necessary – our death, a joy which the world cannot give but which the world cannot take away.

I will end on one example of this joy of the Spirit. I met a few years ago in Russia an elderly priest who had spent 36 years in prisons and concentration camps. He sat opposite me with eyes shining with joy and gratitude and he said, “Do you realise, can you imagine, how infinitely good God had been to me? The Soviet authorities did not allow a priest either into prisons or into camps; and He chooses me, a young, inexperienced priest and sends me first to prison and then to camp to look after his lost sheep.” There was nothing in him but gratitude and joy. And that joy, that kind of gratitude against the history of his life was truly an outpouring of the Holy Spirit.

Let us therefore in all our life, whether we pray, listen to the unutterable groanings of the Spirit within us, teaching us ultimately to call the God of Heaven our Father if we are in Jesus Christ, in the words of Irenaeus of Lyon, sons of God in the Only-Begotten Son of God. Let us open ourselves and listen intently when we have got to preach, so that it should not be a work of our intellect or learning but a sharing of something which we have learnt from God. However poor, childlike, simple it may seem, let it be God’s. And when we come to the celebration of the Holy Mysteries, let us remember that we stand where no-one can stand but the High Priest of all creation, the Lord Jesus Christ and let us turn to the Holy Spirit calling Him to make the bread and the wine into the Body and Blood of Christ in an act Divine which we can only mediate by faith and in obedience to Christ’s own command. Amen.