Prayer and Work

As Benedictine monks, we approach prayer in a distinctive, monastic way. We pray the Psalms, those ancient, iron-age poems given to the Church by the people of Israel, at regular times each day. We come together to do this "work of God" and it is the glue that holds our community life together.

The Psalms are a rich repository of human religious experience, at times pleading, cursing, hoping, despairing, grieving, resting, rejoicing, praising, always from a position of profound trust in the saving power of God. Over the centuries, praying monks quickly learned that some of the Psalms were better suited to the morning, some for the evening, and some for midday. They noted that some of them were keyed to the mystery of the dying and rising of Jesus. So our prayer as monks is largely biblical and liturgical, ever responsive to the rhythm of the day and season.

We celebrate Eucharist each day, and with special festivity on Sunday. All of our prayer flows to and from the Sunday Eucharist, recognizing both spiritually and theologically that Christian monastic life would not make any sense without the resurrection of Jesus. Sunday is a "little" Easter!

Our individual prayer is also rooted in the Scriptures. From the earliest days of monastic life, monks have immersed themselves in the language, images, and narrative of the Bible. In the daily practice of reading a short passage of Scripture, pondering its meaning, and praying in and through the text, we continually rediscover the purpose and meaning for our lives and God's work in them. One of the great gifts of the monastic tradition is that we read Scripture continuously, that is, we don't jump around from one passage to another, from one book to another. Rather, we read and pray the Scriptures continuously, always in context.

Another powerful practice from the monastic tradition is centering prayer. Many times individuals find their prayer stymied and unfruitful because they conceive of it as human beings "talking to God." Centering prayer rebalances this equation because in this practice we simply sit in silence, in the presence of God, and let the Holy Spirit "work on us." Initially, because we are not speaking, our minds rush around, grabbing at everything. But with practice, we learn to let go of the mind's activity and to be in silence before God, who, as Saint Benedict teaches, is everywhere.

Monks work. They understand work as a normal, creative expression of being alive as a human being. They do everything from pastoring to teaching, administrating, repairing and maintaining the monastery, and growing food for the table. Saint Benedict instructs his monks that they should not complain if they have to "do the harvest," thereby ensuring that later generations of monks would respect all honest labor.

Note that the title of this section is "prayer and work." The conjunction "and" is extremely important because we are always struggling to maintain the balance between the two, between prayer and work. If we tip in either direction, we will surely be less than optimal in our search for union with God. Too much time in prayer can easily turn into a self-serving narcissism that is unaware of the needs of others. Too much work can easily lead one to rationalize being absent from community prayer, Eucharist, holy reading, and the life of the community. Prayer and work, in balance, are a sound-bite that expresses a distinctive element of Benedictine monastic spirituality.

Abbot John Klassen, OSB

June 25, 2013

The Spiritual Art of Lectio Divina

Prayer is at the center of Benedictine life. Understood as “the work of God,” lectio divina and the liturgy of the hours are among the first concerns in the day of monk. As a shared calling, prayer brings the differences and various pursuits of a community together with a common role and identity as monks. Prayer is a comfort in times of distress, a resource when in need, a selfless sharing and outpouring in times of success and joy. Prayer is so fully a part of the “ins and outs” monastic life, that it establishes the pattern and rhythm of the day through the dynamic interchange of worship and work. We come together each day to pray the liturgy of the hours and celebrate the Eucharist, but lectio divina, though usually a private practice, is also fundamental to the Benedictine life of prayer, and is essential to living and growing in Benedictine identity and spirituality.

“Lectio divina” translates to “divine reading,” meaning a prayerful reading of Holy Scripture, and other spiritual texts. Though often referred to by its Latin title, striking some as distant or foreign, the practice is really very common. It may be that the practitioner does not realize they are praying in the lectio divina fashion. Active and fundamental to the whole of the 2,000 years of Christian Tradition, and inherited from the Jewish reverence of Scripture, lectio divina is an open, hopeful and faithful trust and listening to God revealed in the Old and New Testaments, as well as the Spirit-filled writings and instructions of the Church. In short, every time you take a moment from your day to read from these writings in faith, hope and love, you are practicing lectio divina.

Cultural2.jpgBeginning and returning again and again to Scripture in lectio divina is a trustworthy spiritual practice, even without extensive instruction. However, committing yourself to lectio divina can be challenging, and as a private spiritual practice, an exclusion of conversation and guidance within the Church community can lead to misunderstandings. As a 2,000 year-old form of Christian prayer, many words of advice and methods have been developed and inherited throughout the Church Tradition for the purpose of helping establish this practice as a perpetual and reliable part of Christian life and spirituality.

An excellent introduction we favor and recommend is Accepting the Embrace of God:The Ancient Art of Lectio Divina by Fr. Luke Dysinger, O.S.B., from Saint Andrew's Abbey in Valyermo, California.

Accepting the Embrace of God: The Ancient Art of Lectio Divina

by Fr. Luke Dysinger, O.S.B.

1. THE PROCESS of LECTIO DIVINA

A VERY ANCIENT art, practiced at one time by all Christians, is the technique known as lectio divina - a slow, contemplative praying of the Scriptures which enables the Bible, the Word of God, to become a means of union with God. This ancient practice has been kept alive in the Christian monastic tradition, and is one of the precious treasures of Benedictine monastics and oblates. Together with the Liturgy and daily manual labor, time set aside in a special way for lectio divina enables us to discover in our daily life an underlying spiritual rhythm. Within this rhythm we discover an increasing ability to offer more of ourselves and our relationships to the Father, and to accept the embrace that God is continuously extending to us in the person of his Son Jesus Christ.

Lectio - reading/listening

THE ART of lectio divina begins with cultivating the ability to listen deeply, to hear “with the ear of our hearts” as St. Benedict encourages us in the Prologue to the Rule. When we read the Scriptures we should try to imitate the prophet Elijah. We should allow ourselves to become women and men who are able to listen for the still, small voice of God (I Kings 19:12); the “faint murmuring sound” which is God's word for us, God's voice touching our hearts. This gentle listening is an “atunement” to the presence of God in that special part of God's creation which is the Scriptures.

THE CRY of the prophets to ancient Israel was the joy-filled command to “Listen!” “Sh'ma Israel: Hear, O Israel!” In lectio divina we, too, heed that command and turn to the Scriptures, knowing that we must “hear” - listen - to the voice of God, which often speaks very softly. In order to hear someone speaking softly we must learn to be silent. We must learn to love silence. If we are constantly speaking or if we are surrounded with noise, we cannot hear gentle sounds. The practice of lectio divina, therefore, requires that we first quiet down in order to hear God's word to us. This is the first step of lectio divina, appropriately called lectio - reading.

THE READING or listening which is the first step in lectio divina is very different from the speed reading which modern Christians apply to newspapers, books and even to the Bible. Lectio is reverential listening; listening both in a spirit of silence and of awe. We are listening for the still, small voice of God that will speak to us personally - not loudly, but intimately. In lectio we read slowly, attentively, gently listening to hear a word or phrase that is God's word for us this day.

Meditatio - meditation

ONCE WE have found a word or a passage in the Scriptures that speaks to us in a personal way, we must take it in and “ruminate” on it. The image of the ruminant animal quietly chewing its cud was used in antiquity as a symbol of the Christian pondering the Word of God. Christians have always seen a scriptural invitation to lectio divina in the example of the Virgin Mary “pondering in her heart” what she saw and heard of Christ (Luke 2:19). For us today these images are a reminder that we must take in the word - that is, memorize it - and while gently repeating it to ourselves, allow it to interact with our thoughts, our hopes, our memories, our desires. This is the second step or stage in lectio divina - meditatio. Through meditatio we allow God's word to become His word for us, a word that touches us and affects us at our deepest levels.

Oratio - prayer

THE THIRD step in lectio divina is oratio - prayer: prayer understood both as dialogue with God, that is, as loving conversation with the One who has invited us into His embrace; and as consecration, prayer as the priestly offering to God of parts of ourselves that we have not previously believed God wants. In this consecration-prayer we allow the word that we have taken in and on which we are pondering to touch and change our deepest selves. Just as a priest consecrates the elements of bread and wine at the Eucharist, God invites us in lectio divina to hold up our most difficult and pain-filled experiences to Him, and to gently recite over them the healing word or phrase He has given us in our lectio and meditatio. In this oratio, this consecration-prayer, we allow our real selves to be touched and changed by the word of God.

THE THIRD step in lectio divina is oratio - prayer: prayer understood both as dialogue with God, that is, as loving conversation with the One who has invited us into His embrace; and as consecration, prayer as the priestly offering to God of parts of ourselves that we have not previously believed God wants. In this consecration-prayer we allow the word that we have taken in and on which we are pondering to touch and change our deepest selves. Just as a priest consecrates the elements of bread and wine at the Eucharist, God invites us in lectio divina to hold up our most difficult and pain-filled experiences to Him, and to gently recite over them the healing word or phrase He has given us in our lectio and meditatio. In this oratio, this consecration-prayer, we allow our real selves to be touched and changed by the word of God.

Contemplatio - contemplation

FINALLY, WE simply rest in the presence of the One who has used His word as a means of inviting us to accept His transforming embrace. No one who has ever been in love needs to be reminded that there are moments in loving relationships when words are unnecessary. It is the same in our relationship with God. Wordless, quiet rest in the presence of the One Who loves us has a name in the Christian tradition - contemplatio, contemplation. Once again we practice silence, letting go of our own words; this time simply enjoying the experience of being in the presence of God.

2. THE UNDERLYING RHYTHM of LECTIO DIVINA

IF WE are to practice lectio divina effectively, we must travel back in time to an understanding that today is in danger of being almost completely lost. In the Christian past the words action (or practice, from the Greek praktikos) and contemplation did not describe different kinds of Christians engaging (or not engaging) in different forms of prayer and apostolates. Practice and contemplation were understood as the two poles of our underlying, ongoing spiritual rhythm: a gentle oscillation back and forth between spiritual “activity” with regard to God and “receptivity.”

PRACTICE - spiritual “activity” - referred in ancient times to our active cooperation with God's grace in rooting out vices and allowing the virtues to flourish. The direction of spiritual activity was not outward in the sense of an apostolate, but inward - down into the depths of the soul where the Spirit of God is constantly transforming us, refashioning us in God's image. The active life is thus coming to see who we truly are and allowing ourselves to be remade into what God intends us to become.

IN THE early monastic tradition contemplation was understood in two ways. First was theoria physike, the contemplation of God in creation - God in “the many.” Second was theologia, the contemplation of God in Himself without images or words - God as “The One.” From this perspective lectio divina serves as a training-ground for the contemplation of God in His creation.

IN CONTEMPLATION we cease from interior spiritual doing and learn simply to be, that is to rest in the presence of our loving Father. Just as we constantly move back and forth in our exterior lives between speaking and listening, between questioning and reflecting, so in our spiritual lives we must learn to enjoy the refreshment of simply being in God's presence, an experience that naturally alternates (if we let it!) with our spiritual practice.

IN ANCIENT times contemplation was not regarded as a goal to be achieved through some method of prayer, but was simply accepted with gratitude as God's recurring gift. At intervals the Lord invites us to cease from speaking so that we can simply rest in his embrace. This is the pole of our inner spiritual rhythm called contemplation.

HOW DIFFERENT this ancient understanding is from our modern approach! Instead of recognizing that we all gently oscillate back and forth between spiritual activity and receptivity, between practice and contemplation, we today tend to set contemplation before ourselves as a goal - something we imagine we can achieve through some spiritual technique. We must be willing to sacrifice our “goal-oriented” approach if we are to practice lectio divina, because lectio divina has no other goal than spending time with God through the medium of His word. The amount of time we spend in any aspect of lectio divina, whether it be rumination, consecration or contemplation depends on God's Spirit, not on us. Lectio divina teaches us to savor and delight in all the different flavors of God's presence, whether they be active or receptive modes of experiencing Him.

IN lectio divina we offer ourselves to God; and we are people in motion. In ancient times this inner spiritual motion was described as a helix - an ascending spiral. Viewed in only two dimensions it appears as a circular motion back and forth; seen with the added dimension of time it becomes a helix, an ascending spiral by means of which we are drawn ever closer to God. The whole of our spiritual lives were viewed in this way, as a gentle oscillation between spiritual activity and receptivity by means of which God unites us ever closer to Himself. In just the same way the steps or stages of lectio divina represent an oscillation back and forth between these spiritual poles. In lectio divina we recognize our underlying spiritual rhythm and discover many different ways of experiencing God's presence - many different ways of praying.

3. THE PRACTICE of LECTIO DIVINA

Private Lectio Divina

CHOOSE a text of the Scriptures that you wish to pray. Many Christians use in their daily lectio divina one of the readings from the Eucharistic liturgy for the day; others prefer to slowly work through a particular book of the Bible. It makes no difference which text is chosen, as long as one has no set goal of “covering” a certain amount of text: the amount of text “covered” is in God's hands, not yours.

PLACE YOURSELF in a comfortable position and allow yourself to become silent. Some Christians focus for a few moments on their breathing; other have a beloved “prayer word” or “prayer phrase” they gently recite in order to become interiorly silent. For some the practice known as “centering prayer” makes a good, brief introduction to lectio divina. Use whatever method is best for you and allow yourself to enjoy silence for a few moments.

THEN TURN to the text and read it slowly, gently. Savor each portion of the reading, constantly listening for the “still, small voice” of a word or phrase that somehow says, “I am for you today.” Do not expect lightening or ecstasies. In lectio divina God is teaching us to listen to Him, to seek Him in silence. He does not reach out and grab us; rather, He softly, gently invites us ever more deeply into His presence.

NEXT TAKE the word or phrase into yourself. Memorize it and slowly repeat it to yourself, allowing it to interact with your inner world of concerns, memories and ideas. Do not be afraid of “distractions.” Memories or thoughts are simply parts of yourself which, when they rise up during lectio divina, are asking to be given to God along with the rest of your inner self. Allow this inner pondering, this rumination, to invite you into dialogue with God.

THEN, SPEAK to God. Whether you use words or ideas or images or all three is not important. Interact with God as you would with one who you know loves and accepts you. And give to Him what you have discovered in yourself during your experience of meditatio. Experience yourself as the priest that you are. Experience God using the word or phrase that He has given you as a means of blessing, of transforming the ideas and memories, which your pondering on His word has awakened. Give to God what you have found within your heart.

FINALLY, SIMPLY rest in God's embrace. And when He invites you to return to your pondering of His word or to your inner dialogue with Him, do so. Learn to use words when words are helpful, and to let go of words when they no longer are necessary. Rejoice in the knowledge that God is with you in both words and silence, in spiritual activity and inner receptivity.

SOMETIMES IN lectio divina one will return several times to the printed text, either to savor the literary context of the word or phrase that God has given, or to seek a new word or phrase to ponder. At other times only a single word or phrase will fill the whole time set aside for lectio divina. It is not necessary to anxiously assess the quality of one's lectio divina as if one were “performing” or seeking some goal: lectio divina has no goal other than that of being in the presence of God by praying the Scriptures.

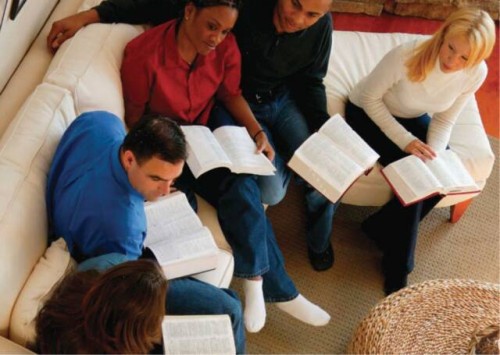

Lectio Divina as a Group Exercise

THE most authentic and traditional form of Christian lectio divina is the solitary or “private” practice described to this point. In recent years, however, many different forms of so-called “group lectio” have become popular and are now widely-practiced. These group exercises can be very useful means of introducing and encouraging the practice of lectio divina; but they should not become a substitute for an encounter and communion with the Living God that can only take place in that privileged solitude where the biblical Word of God becomes transparent to the Very Word Himself - namely private lectio divina.

IN churches of the Third World where books are rare, a form of corporate lectio divina is becoming common in which a text from the Scriptures is pondered by Christians praying together in a group. The method of group lectio divina described here was introduced at St. Andrew's Abbey by oblates Doug and Norvene Vest: it is used as part of the Benedictine Spirituality for Laity workshops conducted at the Abbey each summer.

THIS FORM of lectio divina works best in a group of between four and eight people. A group leader coordinates the process and facilitates sharing. The same text from the Scriptures is read out three times, followed each time by a period of silence and an opportunity for each member of the group to share the fruit of her or his lectio.

THE FIRST reading (the text is actually read twice on this occasion) is for the purpose of hearing a word or passage that touches the heart. When the word or phrase is found, it is silently taken in, and gently recited and pondered during the silence which follows. After the silence each person shares which word or phrase has touched his or her heart.

THE SECOND reading (by a member of the opposite sex from the first reader) is for the purpose of “hearing” or “seeing” Christ in the text. Each ponders the word that has touched the heart and asks where the word or phrase touches his or her life that day. In other words, how is Christ the Word touching his own experience, his own life? How are the various members of the group seeing or hearing Christ reach out to them through the text? Then, after the silence, each member of the group shares what he or she has “heard” or “seen.”

THE THIRD and final reading is for the purpose of experiencing Christ “calling us forth” into doing or being. Members ask themselves what Christ in the text is calling them to do or to become today or this week. After the silence, each shares for the last time; and the exercise concludes with each person praying for the person on the right.

THOSE WHO who regularly practice this method of praying and sharing the Scriptures regularly find it to be an excellent way of developing trust within a group; it also is an excellent way of consecrating projects and hopes to Christ before more formal group meetings. A summary of this method for group lectio divina is appended at the end of this article.

Lectio Divina on Life

IN THE ancient tradition lectio divina was understood as being one of the most important ways in which Christians experience God in creation. After all, the Scriptures are part of creation! If one is daily growing in the art of finding Christ in the pages of the Bible, one naturally begins to discover Him more clearly in aspects of the other things He has made. This includes, of course, our own personal history.

OUR OWN lives are fit matter for lectio divina. Very often our concerns, our relationships, our hopes and aspirations naturally intertwine with our pondering on the Scriptures, as has been described above. But sometimes it is fitting to simply sit down and “read” the experiences of the last few days or weeks in our hearts, much as we might slowly read and savor the words of Scripture in lectio divina. We can attend “with the ear of our hearts” to our own memories, listening for God's gentle presence in the events of our lives. We thus allow ourselves the joy of experiencing Christ reaching out to us through our own memories. Our own personal story becomes “salvation history.”

FOR THOSE who are new to the practice of lectio divina a group experience of “lectio on life” can provide a helpful introduction. An approach that has been used at workshops at St. Andrew's Priory is detailed at the end of this article. Like the experience of lectio divina shared in community, this group experience of lectio on life can foster relationships in community and enable personal experiences to be consecrated - offered to Christ - in a concrete way.

HOWEVER, UNLIKE scriptural lectio divina shared in community, this group lectio on life contains more silence than sharing. The role of group facilitators or leaders is important, since they will be guiding the group through several periods of silence and reflection without the “interruption” of individual sharing until the end of the exercise. Since the experiences we choose to “read” or “listen to” may be intensely personal, it is important in this group exercise to safeguard privacy by making sharing completely optional.

IN BRIEF, one begins with restful silence, then gently reviews the events of a given period of time. One seeks an event, a memory, which touches the heart just as a word or phrase in scriptural lectio divina does. One then recalls the setting, the circumstances; one seeks to discover how God seemed to be present or absent from the experience. One then offers the event to God and rests for a time in silence. A suggested method for group lectio divina on life is given in the Appendix to this article.

CONCLUSION

LECTIO DIVINA is an ancient spiritual art that is being rediscovered in our day. It is a way of allowing the Scriptures to become again what God intended that they should be - a means of uniting us to Himself. In lectio divina we discover our own underlying spiritual rhythm. We experience God in a gentle oscillation back and forth between spiritual activity and receptivity, in the movement from practice into contemplation and back again into spiritual practice.

LECTIO DIVINA teaches us about the God who truly loves us. In lectio divina we dare to believe that our loving Father continues to extend His embrace to us today. And His embrace is real. In His word we experience ourselves as personally loved by God; as the recipients of a word which He gives uniquely to each of us whenever we turn to Him in the Scriptures.

FINALLY, lectio divina teaches us about ourselves. In lectio divina we discover that there is no place in our hearts, no interior corner or closet that cannot be opened and offered to God. God teaches us in lectio divina what it means to be members of His royal priesthood - a people called to consecrate all of our memories, our hopes and our dreams to Christ.

APPENDIX: TWO APPROACHES to GROUP LECTIO DIVINA

1. Lectio Divina Shared in Community

(A) Listening for the Gentle Touch of Christ the Word

(The Literal Sense)

1. One person reads aloud (twice) the passage of scripture, as others are attentive to some segment that is especially meaningful to them.

2. Silence for 1-2 minutes. Each hears and silently repeats a word or phrase that attracts.

3. Sharing aloud: [A word or phrase that has attracted each person]. A simple statement of one or a few words. No elaboration.

(B) How Christ the Word speaks to ME

(The Allegorical Sense)

4. Second reading of same passage by another person.

5. Silence for 2-3 minutes. Reflect on “Where does the content of this reading touch my life today?”

6. Sharing aloud: Briefly: “I hear, I see...”

(C) What Christ the Word Invites me to DO

(The Moral Sense)

7. Third reading by still another person.

8. Silence for 2-3 minutes. Reflect on “I believe that God wants me to . . . . . . today/this week.”

9. Sharing aloud: at somewhat greater length the results of each one's reflection. [Be especially aware of what is shared by the person to your right.]

10. After full sharing, pray for the person to your right.

Note: Anyone may “pass” at any time. If instead of sharing with the group you prefer to pray silently , simply state this aloud and conclude your silent prayer with Amen.

2. Lectio on Life: Applying Lectio Divina to my personal Salvation History

Purpose: to apply a method of prayerful reflection to a life/work incident (instead of to a scripture passage)

(A) Listening for the Gentle Touch of Christ the Word

(The Literal Sense)

1. Each person quiets the body and mind: relax, sit comfortably but alert, close eyes, attune to breathing...

2. Each person gently reviews events, situations, sights, encounters that have happened since the beginning of the retreat/or during the last month at work.

(B) Gently Ruminating, Reflecting

(Meditatio - Meditation)

3. Each person allows the self to focus on one such offering.

a) Recollect the setting, sensory details, sequence of events, etc.

b) Notice where the greatest energy seemed to be evoked. Was there a turning point or shift?

c) In what ways did God seem to be present? To what extent was I aware then? Now?

(C) Prayerful Consecration, Blessing

(Oratio - Prayer)

4. Use a word or phrase from the Scriptures to inwardly consecrate - to offer up to God in prayer - the incident and interior reflections. Allow God to accept and bless them as your gift.

(D) Accepting Christ's Embrace; Silent Presence to the Lord

(Contemplatio - Contemplation)

5. Remain in silence for some period.

(E) Sharing our Lectio Experience with Each Other

(Operatio - Action; works)

6. Leader calls the group back into “community.”

7. All share briefly (or remain in continuing silence).