In this short essay, I am going to discuss some signs of hope, solid reasons to believe that the Catholic - Orthodox schism will not last for ever; but, at the same time, I will argue that reunion will not happen soon: we still have a long way to go, principally because we need time to grow together, to have confidence in one another, even to like one another, before there will be sufficient impetus to tackle the more intractable problems.

My optimism stems from several reasons: firstly, that for the first time in history since Constantine's conversion, it is clear that Eastern and Western Christianity face the same problems because we live in the same global society; secondly, that, since Vatican II, Orthodoxy and Catholicism are looking at their differences within the context of the same eucharistic ecclesiology; thirdly, such concepts and words as "theosis" and "synergy" and the transcendentals "the good", the "true" and the "beautiful" are now commonplace and central in Catholic as well as Orthodox theology. Moreover, I would suggest, that at least some Orthodox and Catholic theologians, people of the same line of thought as Pope Benedict and of Metropolitan John Zizioulas, think that answers to the main problems may well lie in what Pope Benedict calls the "hermeneutic of continuity". This last phrase was not made up to argue for a traditionalist interpretation of Vatican II nor for a return to the post-Tridentine Mass: it is one of the most important and most basic ideas of Pope Benedict and of the school of thought most active in Vatican II to which he belonged.

This group was centred on Paris and Lyons, were mostly Jesuits and Dominicans, though Louis Bouyer was an Oratorian. There was nothing formal about the group. They may not have even considered themselves to be a group at first; but they had a community of interest. They saw the Church in crisis, a church which had largely lost the working class. They believed that "secular values" were encouraged by a too stark separation in the theology of their day between "natural" and "supernatural". They held that mankind has a natural desire for God, and that the main reason why the people were falling away was because they were starved of the sacred. This could only be rectified by liturgical reform because the people were cut off from the sacred by a completely latinised and clericalised liturgy. They subjected the theology of their time to a stringent critique. As several of them were patristic scholars, they compared the modern Church unfavourably with the Church of the Fathers. This group is immensely important because a) they had formed their ideas in France where a group of extremely able Russian Orthodox theologians had taken refuge; also b) because a young archbishop of Cracow called Carol Wojtyla and a young German theologian called Joseph Ratzinger along with others like Dom Christopher Butler OSB of Downside joined them in the council; and c) because they were involved in writing the most important Vatican II documents.

They were opposed by the so-called "conservative" position that was commonly held before the council in which the Church's grasp of God's revelation in Christ had been encapsulated in ever clearer propositions over the centuries under the guidance of the Holy Spirit so that all we have to do to understand Catholic Truth is to listen to the teaching of the present day Magisterium and to interpret history in the light of its teaching. History may be used to prove the truth of the modern Church's teaching, but it is never used to criticise it. For "conservatives", the idea that a critical study of church history could be used to call in question the present-day teaching and practice of the Church looked too much like modernism.

This group was centred on Paris and Lyons, were mostly Jesuits and Dominicans, though Louis Bouyer was an Oratorian. There was nothing formal about the group. They may not have even considered themselves to be a group at first; but they had a community of interest. They saw the Church in crisis, a church which had largely lost the working class. They believed that "secular values" were encouraged by a too stark separation in the theology of their day between "natural" and "supernatural". They held that mankind has a natural desire for God, and that the main reason why the people were falling away was because they were starved of the sacred. This could only be rectified by liturgical reform because the people were cut off from the sacred by a completely latinised and clericalised liturgy. They subjected the theology of their time to a stringent critique. As several of them were patristic scholars, they compared the modern Church unfavourably with the Church of the Fathers. This group is immensely important because a) they had formed their ideas in France where a group of extremely able Russian Orthodox theologians had taken refuge; also b) because a young archbishop of Cracow called Carol Wojtyla and a young German theologian called Joseph Ratzinger along with others like Dom Christopher Butler OSB of Downside joined them in the council; and c) because they were involved in writing the most important Vatican II documents.

They were opposed by the so-called "conservative" position that was commonly held before the council in which the Church's grasp of God's revelation in Christ had been encapsulated in ever clearer propositions over the centuries under the guidance of the Holy Spirit so that all we have to do to understand Catholic Truth is to listen to the teaching of the present day Magisterium and to interpret history in the light of its teaching. History may be used to prove the truth of the modern Church's teaching, but it is never used to criticise it. For "conservatives", the idea that a critical study of church history could be used to call in question the present-day teaching and practice of the Church looked too much like modernism.

The way the new school of theologians used history laid them open to charges of "modernism" in the twenty or so years before Vatican II, and they only came out from under that cloud where the Vatican had placed them when some were invited by Pope John XXIII to take part in Vatican II, and others accompanied their bishops to the council.. The continuity that is so basic to their thought is not something theologians have invented, nor does it exist only at a theoretical level, nor is it something the pope, the bishops or the theologians have completely under their control; nor is it a mere product of the Magisterium: the Magisterium is its servant. It is nothing less than the continuity of Tradition; and Tradition is the product of the synergy between the Holy Spirit and the life of the Church, with the Holy Spirit enabling it to happen and the Church allowing it to happen by its humble obedience.

Tradition is only partly the transmission of ideas. It is also continuity of celebration and continuity in participation in the vision of faith and of the Christ-life. As George Florovsky wrote about patristic theology:

It is by sharing their "mind" that we can think, pray and act within Tradition. Only if we have the vision of faith, given by the Spirit, can we make head or tale of the Truth that the formulas express. When I was studying theology in the early sixties, we did not call the theology of de Lubac, Danielou etc resourcement theology; we called it kerygmatic theology. Reading Florovsky, we can begin to understand why: it is embedded in the liturgical tradition of the Church and proclaimed in the kerygma, and theological reflection can never separate it's formulations from the Christian ecclesial life of faith that gives them substance.

Tradition being the product of the Holy Spirit and the Church acting in synergy, popes, bishops, general councils and faithful are subject to it, and not the other way round. It is the context in which the New Testament was written, its books were recognised and are read and interpreted, the liturgies of the Church were formed and have developed, where dogmas have been expressed in words and interpreted. If you want to see the role of Tradition in the Catholic Church, then read the teachings of Vatican II and some of the words and actions of Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

Tradition is only partly the transmission of ideas. It is also continuity of celebration and continuity in participation in the vision of faith and of the Christ-life. As George Florovsky wrote about patristic theology:

In the age of theological strife and incessant debates, the great Cappadocian Fathers protested against the use of dialectics, of Aristotelian syllogisms, and endeavoured to refer theology back to the vision of faith.

Patristic theology could only be "preached" or "proclaimed" - preached from the pulpit, proclaimed also in the words of prayer and in the sacred rites, and indeed manifested in the total structure of Christian life. Theology of this kind can never be separated from the life of prayer and from the exercise of virtue. "The climax of purity is the beginning of theology," as St John the Klimakos put it. (Scala Paradisi, grade 30)

On the other hand, theology of this type is always, as it were, "propaideutic," since its ultimate aim and purpose is to ascertain and to acknowledge the Mystery of the Living God, and indeed to bear witness to it in word and deed. Theology is not an end in itself, but a way. Theology, and even the "dogmas" present no more than an "intellectual contour" of the revealed truth, and a "noetic" testimony to it. Only in the act of faith is this "contour" filled with content. Christological formulas are fully meaningful only for those who have encountered the Living Christ, and have received and acknowledged Him as God and Saviour, and are dwelling by faith in Him, in His body, the Church. In this sense, theology is never a self-explanatory discipline. It is constantly appealing to the vision of faith. "What we have seen and heard we have announced to you." Apart from this "announcement", theological formulas are empty and of no consequence....To follow the Fathers does not mean to quote them. To follow the Fathers means to acquire their "mind", their phronema.

It is by sharing their "mind" that we can think, pray and act within Tradition. Only if we have the vision of faith, given by the Spirit, can we make head or tale of the Truth that the formulas express. When I was studying theology in the early sixties, we did not call the theology of de Lubac, Danielou etc resourcement theology; we called it kerygmatic theology. Reading Florovsky, we can begin to understand why: it is embedded in the liturgical tradition of the Church and proclaimed in the kerygma, and theological reflection can never separate it's formulations from the Christian ecclesial life of faith that gives them substance.

Tradition being the product of the Holy Spirit and the Church acting in synergy, popes, bishops, general councils and faithful are subject to it, and not the other way round. It is the context in which the New Testament was written, its books were recognised and are read and interpreted, the liturgies of the Church were formed and have developed, where dogmas have been expressed in words and interpreted. If you want to see the role of Tradition in the Catholic Church, then read the teachings of Vatican II and some of the words and actions of Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI.

Because bishops, councils and theologians are not the masters of Tradition but its servants, Vatican II made no attempt to solve the problems between East and West, even though this was very much in the mind of many: they waited on the action of the Holy Spirit, and the Catholic Church continues to wait for the gradual or rapid growing together of the two traditions under the influence of the same Spirit. It is only then that things can become clear. This is so because Catholic theologians are confident, as George Florovsky said, that the two versions of Catholic Tradition belong together. Thus, people like Joseph Ratzinger knew that the eucharistic ecclesiology favoured by Vatican II, with the powers of the Church arising from the celebration of the Eucharist, is a profounder, more basic insight into the nature of the Church than that of Vatican I of a Church that is a perfect society, held together by papal universal jurisdiction that was legally delegated to Peter by Christ. If the priority of its eucharistic dimension over its legal structure is forgotten, then the laws that the Church must have in order to function as one body throughout the world will appear like any other laws, and the clear distinction taught by Christ between authorities in the Church and authorities in the world will be forgotten. Nevertheless, as Catholics, they cannot deny Vatican I's place in Catholic Tradition. Hence they simply put the two views side by side, fully knowing that, in time, the profounder view would modify the interpretation of the Vatican I view almost out of recognition; but there would be an inner continuity, leaving the papacy intact to operate in a new context of a more fully Catholic Tradition of both East and West. In this situation, John Paul II asked help in Ut Unum Sint from our separated brethren.

In this regard, it may be a good idea to notice why the group of theologians, centred on France, to which Wotlyla and Ratzinger attached themselves in Vatican II, were considered dangerous by the Vatican, who suspected them of modernism. They were called resourcement theologians because they wanted to return to the sources. Basic to their theology was Tradition which maintains the same relationship with the Spirit at any particular moment, from the time of the Apostles until now. There is a continuity which allows for growth in clarity and profundity, but they also saw that aspects of the Truth have been forgotten, exaggerated and even distorted. Our present grasp of the Truth can be modified by the way the Truth was grasped in earlier times. Scripture and the time of the Fathers are particularly authoritative; and modern problems may well have solutions in the past. For the resourcement theologians, modern interpretation, like the interpretation of any other particular time, is subject to Tradition as a whole - the hermeneutic of continuity - and they even claimed that there had been a deterioration of our understanding of the Church and of the sacraments, and that there was a crying need for a fuller understanding and reform of the liturgy, and that the Church of the Fathers had a better understanding and a better practice in these areas. All this was believed while they also held that the insights and practices accepted by the Church in later centuries are also true, because the Holy Spirit has not ceased to guide the Church.

Since we have used the papacy as an example of an institution that needs correction by Tradition, I shall now give you a short passage from Yves Congar OP on church authority. He was an important peritus or expert in Vatican II and belonged to the resourcement group, a friend of Joseph Ratzinger. It is a good illustration of the past correcting the present, and was published near the end of the Council in 1964. It is called in French "Pour une Eglise Servante et Pauvre", which shows us that Pope Francis is on track!

The change from a sacramental way of interpreting the authority of the Church to a legalistic one arose from the habit of popes comparing their authority with that of emperors, and of archbishops like St Thomas a Becket with that of kings. Also there was the separation of theology from cult as theological activity went away from monasteries and cathedrals and into universities. This weakened its essential connection with the liturgy and Christian living. As the Church came to be seen as a world-wide perfect society, held together by papal jurisdiction, so jurisdiction was separated from the celebration of the Eucharist in which Christ himself is actively engaged in deepening our understanding through the liturgy, as we collaborate through humble obedience. Finally, to fit in with the idea of the Church as a perfect society, the Eucharist and the Church lost the sense of participating in the heavenly liturgy. This affected the concept of authority in the Church which became secularised, functioning like any other authority.

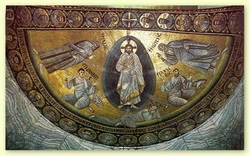

It is in the Roman liturgy's participation in the heavenly liturgy that St Peter is really connected with the church of Rome, and how the Roman Church is united to all other places where the Eucharist is celebrated. St Peter and St Paul are buried there, and their bodies await resurrection on the Last Day.

The Roman Eucharist, like the Eucharist in Constantinople and Moscow, embraces heaven where our divisions don't exist as they do on earth, but the Romans have a special relationship with these two apostles; and this relationship, especially with St Peter, is bound to be reflected from time to time in the words of the Roman bishop, "Peter speaks through the mouth of Leo!"

The way to reunion with the Orthodox is, as far as we are concerned, the way of making the insights of Vatican II a concrete reality. There is much yet to be done, but it is marked out for us in the documents of the Council.

Since we have used the papacy as an example of an institution that needs correction by Tradition, I shall now give you a short passage from Yves Congar OP on church authority. He was an important peritus or expert in Vatican II and belonged to the resourcement group, a friend of Joseph Ratzinger. It is a good illustration of the past correcting the present, and was published near the end of the Council in 1964. It is called in French "Pour une Eglise Servante et Pauvre", which shows us that Pope Francis is on track!

We have...studied...the history of the expression Vicarius Christi as a papal title. The use of the title has continued but its meaning has changed. Its older sense in Catholic theology was that of a visible representative of a transcendent and heavenly power which was actually active in its earthly representative. The context and atmosphere surrounding the idea were those of the actuality of the action of God, Christ and the saints working in their representative. This is a very sacramental, iconological concept linked to the idea of the constant presences of God and the celestial powers in our earthly sphere. It is this quality of actuality and of "vertical" descent and a presence which has its source in the celebrated text in Luke 10: 16, "Whoever listens to you listens to me, and whoever rejects you rejects me." Although this quality does not disappear, it is overlaid by another quality which is also not entirely new - what is new is its marked predominance over the former one - namely a "power" given at the beginning by someone, by Christ, to his "vicar", that is, to a person who takes his place and who hands on to those who come after him, in an historical sequence of transmission and succession, the power thus received. The predominant feature is not a vertical movement, an actual presence, an iconological representation, but the "horizontal" transmission of a power vested in the earthly jurisdiction and which, though received from on high, is genuinely possessed by this jurisdiction which uses it in the same way as any authority may use the power attached to it.

The modern "mystique" of authority in the Church comes from the movement whose characteristics we just described. But, and this is where its strength lies, once again, strength comes from the mystique and not from the legal aspect - it has combined the actuality of the power possessed with the vision of the "vertical" descent of divine power upon the actual historic authority.....I believe that the spirit of the time introduced something new into this continuity [of Tradition], namely, a certain legalistic aspect.....legalism is characteristic of an ecclesiology unrelated to spiritual anthropology, and for which the word ecclesia indicates, not so much the body of the faithful, as the system, the apparatus, the impersonal depositary of the system of rights whose representatives are the clergy or, as it is now called, the hierarchy, and ultimately the pope and the Roman Curia.

The movement back to the sources must go forward until it restores a completely evangelical concept of authority, a concept that willbe fully supernatural and fully communal. We are on the right road, we have gone far to recover the agape beyond mere moralism, the function of the laity, the community, and our mission and service as dimensions essential to and co-extensive with. We have better understanding of the the religious implications of the covenant, and these involve our acceptance of God's gift through faith, and the life of this gift through agape the diakonia, witness and thanksgiving....Since we are returning to a pre-Constantinian situation in a pagan world, since we are aware that we are in a minority, that it is our task to preach Jesus Christ, we are doubtless approaching a period in which, while we shall lose nothing of value acquired in the course of history, we shall recover wholly evangelical ways of exercising authority in the new world in which God calls us to serve him.

The change from a sacramental way of interpreting the authority of the Church to a legalistic one arose from the habit of popes comparing their authority with that of emperors, and of archbishops like St Thomas a Becket with that of kings. Also there was the separation of theology from cult as theological activity went away from monasteries and cathedrals and into universities. This weakened its essential connection with the liturgy and Christian living. As the Church came to be seen as a world-wide perfect society, held together by papal jurisdiction, so jurisdiction was separated from the celebration of the Eucharist in which Christ himself is actively engaged in deepening our understanding through the liturgy, as we collaborate through humble obedience. Finally, to fit in with the idea of the Church as a perfect society, the Eucharist and the Church lost the sense of participating in the heavenly liturgy. This affected the concept of authority in the Church which became secularised, functioning like any other authority.

It is in the Roman liturgy's participation in the heavenly liturgy that St Peter is really connected with the church of Rome, and how the Roman Church is united to all other places where the Eucharist is celebrated. St Peter and St Paul are buried there, and their bodies await resurrection on the Last Day.

The Roman Eucharist, like the Eucharist in Constantinople and Moscow, embraces heaven where our divisions don't exist as they do on earth, but the Romans have a special relationship with these two apostles; and this relationship, especially with St Peter, is bound to be reflected from time to time in the words of the Roman bishop, "Peter speaks through the mouth of Leo!"

The way to reunion with the Orthodox is, as far as we are concerned, the way of making the insights of Vatican II a concrete reality. There is much yet to be done, but it is marked out for us in the documents of the Council.

- We must have a liturgy that celebrates our participation in the liturgy of heaven. This is yet to be realised. Going back to the pre-conciliar past won't help because the extraordinary rite is no better than the novus ordo in that regard.

- We must have true collegiality both world-wide and regionally and allow the episcopates in the regions to make their own decisions. Collegiality and primacy belong together; but this is yet to become a reality in the Church. Here I have hopes that Pope Francis will go further than either John Paul II or Benedict XVI were able to do.

- We must work together with our Orthodox brothers and sisters to evangelise the world. We must never accept the dominance of secularism. If we do, then we are already beaten. We must take it on: we have resources that the secularists cannot even dream about; if they did, they wouldn't be secularists.

- We Catholics must express our belief in the position of the papacy in the Church in non-legalistic terms. Eucharistic ecclesiology shows us that the Church, before it was ever a "perfect society" united by a common law, was a community united by its participation in the same sacraments, especially in the Eucharist. Its unity came from heaven "in Christ", and its this-worldly unity was a manifestation of the heavenly reality. Its laws are based on the divine Love that expresses itself in ecclesial charity; while ordinary civil law is based on force. This ecclesial charity unites Christians with their bishop, unites the bishops with one another and with the successor of St Peter, and all Catholics together as one body. So that ecclesial charity can function in this world, it works through laws, both locally and universally.

- In eucharistic ecclesiology the Catholic Church fully exists in each eucharistic assembly under its bishop; and each eucharistic assembly relates to all other eucharistic assemblies like hosts in a ciborium: they are identical to one another because each is body of Christ. This may well be true in theory; but it is also true in fact that the people making up the eucharistic assembly are imperfect, so that the assembly may well have to be reminded what it stands for and what it believes. As Pope Benedict XVI said on one occasion, his job does not involve imposing beliefs on people, but of reminding them, from time to time, in what beliefs the Catholic faith that they profess involves them. As each local church is identical to all others, this can be done without imposing one church over another. Papal infallibility challanges each local church and each Christian to be themselves.

- It must be recognised that, since the schism, this charisma of Rome can only be done imperfectly, since the pope only represents the western tradition that has its own theological language, distinct fro Orthodox language and there are limitations that arise from that. In other words, Roman Catholicism has its own belief system, just as Orthodoxy has; and a statement of belief cannot be simply separated from its own system, from which it draws its life, and be imposed on the other. Once it moves from one system to the other it subtly changes its meaning and significance. This is the source of much misunderstanding. People like me who believe in both systems have to endure these mutual misunderstandings, but it is worth it because we feel at home in each community Roman infallibility has nothing to do with imposing beliefs on other local churches and doesn't work when dealing with another belief system. Hence, it is good resourcement theology to return to the sources, before the break, and build up from there. This is now recognised by the theologians on both sides and is another sign of hope. We are concentrating on what both sides believed up till the time of the break.

- If the ability of the Church to perceive the truth arises from its union with Christ in the Eucharist, then both sides have the benefit of the guidance of the Holy Spirit. We must take seriously the objections of each side against the other, and not just dismiss them as heretical nonsense. We must accept each side as true because of the Eucharist, but limited by the schism from judging the other side.

- Because it is recognised by both sides in the debate that the "filioque" clause means one thing in Latin and another in Greek, it must be acknowledged by the West that it is totally inappropriate in a Creed that is meant to show the unity of East and West, and must be got rid off as soon as possible, not waiting for some future reunion negotiations. Its inclusion was resisted for centuries by Roman pontiffs against pressure from the Western Empire, and was only accepted in a moment of weakness. Its presence in the Creed has nothing to do with western tradition on the Trinity, and everything to do with causing problems with the East. It must go, because western trinitarian thought can do without it and Greek thought cannot understand it.

- Finally, as the madman Grisha said to the boy Prokhor (St Seraphim of Sarov), when he asked how he could re-build the Church, we must, "Pray, pray, pray."

.